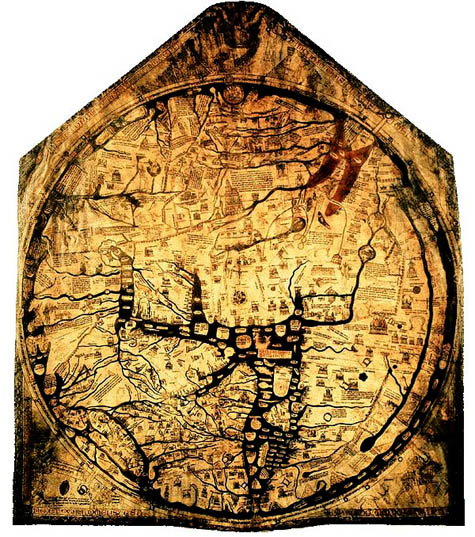

[Image: The charismatic boundaries of an earlier worldview – here, the Hereford Mappa Mundi].

[Image: The charismatic boundaries of an earlier worldview – here, the Hereford Mappa Mundi].

Note: This is a guest post by Nicola Twilley.

Another question for the topic of whether or not a “dense assortment of buildings” can ever be a real city: What is London for an eighteen-year old whose entire urban experience is confined to 200-square meters and who has never seen the Thames?

Researchers at the University of Glasgow, sponsored by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, have spent the past two years asking young residents of Bradford, Peterborough, London, Glasgow, Sunderland, and Bristol to draw maps of their own individual urban experience in order to explore micro-territoriality as both a cause and a symptom of social exclusion. You can read the full PDF of their report here.

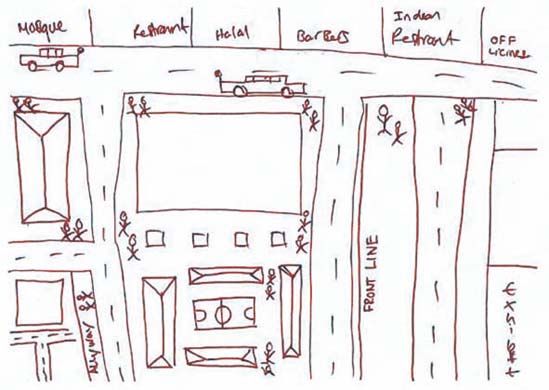

“In Glasgow, Sunderland and Bradford,” they found, “a recognizable territory might be as small as a 200-meter block or segment.” In Tower Hamlets, London, fifteen and sixteen-year old boys mapped their world into three streets, a football pitch, a barber shop, mosque, Indian restaurant, and – just beyond the clearly marked “Front Line” – an off-license, or liquor store.

[Image: From the Joseph Rowntree Foundation report, “Young people and territoriality in British cities” (download the PDF)].

[Image: From the Joseph Rowntree Foundation report, “Young people and territoriality in British cities” (download the PDF)].

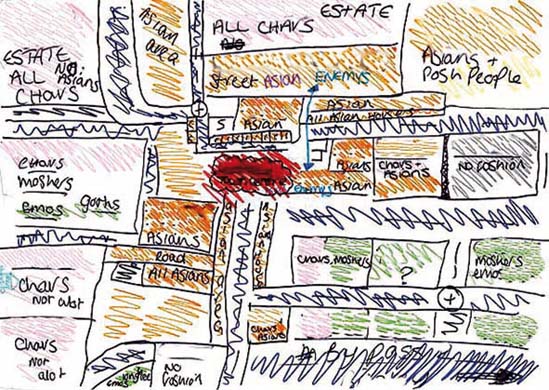

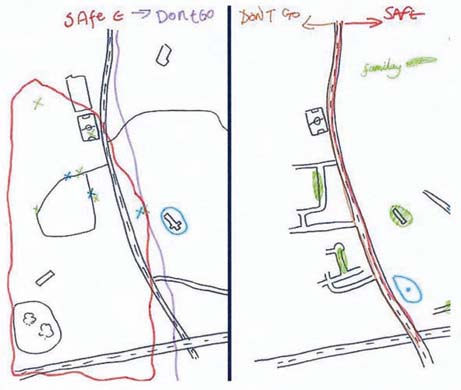

Some of the sketches even remind me of medieval maps: the known world is an island of familiarity, simultaneously shown much larger than scale but made tiny and precious by the monsters of “Terra Incognita” that surround it. In the case of a 15-year-old girl from Bradford, today’s dragons are “moshers,” “chavs,” “Asians,” and “posh people” – all “Enemys.” The researchers found that teenage boys display an even more complete ignorance of the world beyond their perceived boundaries: these two maps of the same area in Glasgow were drawn by young men in the same class at the same school, who live on different sides of the same road.

[Images: From the Joseph Rowntree Foundation report, “Young people and territoriality in British cities” (download the PDF)].

[Images: From the Joseph Rowntree Foundation report, “Young people and territoriality in British cities” (download the PDF)].

The report’s authors examined the causes, nature, and impact of micro-territorialization. Their research uncovered Bristol’s “postcode wars,” where gangs spray-paint their postcode in rival areas as a form of aggression, as well as descriptions of the maneuvers involved in going to school in one part of Bradford that match the Schlieffen Plan in strategic complexity. “In some places,” they note with reference to Glasgow and Sunderland, “territoriality was a leisure activity, a form of ‘recreational violence.’” In other words, bored and economically deprived teenagers are transforming 1960s council estates and Victorian terraces into a real-world, multiplayer World of Warcraft.

Of course, excessive loyalty to the local, and the resulting lack of mobility, has a significant and negative impact on access to education, services, and job opportunities. In the words of one interviewee from Glasgow:

If your horizons are limited to three streets, what is the point of you working really hard at school? What is the point of passing subjects that will allow you to go to college or university if you cannot travel beyond these streets? What’s the point of dreaming about being an artist, a doctor, etc., if you cannot get on a bus to get out of the area in which you live?

The report points out an interesting irony here: current policies in urban regeneration are dominated by strategies to increase “place attachment” as a means “to reinforce social networks and maintain the quality of an area through pride.” However, the areas that actually generate such loyalties are, in the authors’ words “often ones that have little that conventionally invokes pride.”

It was difficult to say which was more depressing – the relentless defense of a featureless piece of open space on the fringes of a Glasgow housing scheme where there is nothing whatsoever by way of amenities, or the confinement to a socially isolated but densely populated and built-up quarter-square-mile of London of young men for whom the culture and wealth of one of the world’s great cities might as well be on another continent.

The report goes on to identify 244 anti-territorial projects (ATPs) currently in progress across the UK. Most use sports or other “hook” activities to encourage association and to teach networking skills. Disappointingly, none tackle the issue in terms of the design of physical space.

So what does the anti-territorial city look like? Some things to consider: unsurprisingly, the report found that most conflicts “occurred on boundaries between residential areas, which were typically defined by roads, railways, vacant land or other physical features.” The city center also becomes a venue for bigger showdowns: a youth worker in Peterborough explains that “the flashpoints are in the city center, the ‘big stage,’ the one place they all, you know, congregate on a Saturday.” Finally, the researchers found that micro-territorialization took place across the spectrum of low-income housing stock, from “high-density, flatted, inner-city estates; traditional, pre-1914 areas of terraced housing; and suburban, often council-built environments.”

As the authors rightly point out, lack of jobs and economic hardship are key structural forces contributing to “problematic territoriality.” But what role does urban planning, landscape design and the built environment have to play?

Can the design of the city itself generate – or mitigate against – territoriality?

(Note: Read the Guardian‘s take on the Joseph Rowntree Foundation report here and here).