[Image: Photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Photo by BLDGBLOG].

In the distant summer of 2002, I worked for a few months at Foster + Partners in London, tasked with helping to archive Foster’s old sketchbooks, hand-drawings, and miscellaneous other materials documenting dozens of different architectural projects over the past few decades.

On a relatively slow afternoon, I was given the job of sorting through some old cupboards full of videocassettes—VHS tapes hoarded more or less randomly, sometimes even without labels, in a small room on the upper floor of the office.

Amongst taped interviews from Foster’s various TV appearances, foreign media documentaries about the office’s international work, and other bits of A/V ephemera, there were a handful of tapes that consisted of nothing but surveillance footage shot inside the old Wembley Stadium.

It was impossible to know what the tapes—unlabeled and shoved in the back of the cupboard—actually documented, but the strange visual language of CCTV is such that something always seems about to happen. There is a strange urgency to surveillance footage, despite its slow, almost glacial pace: a feeling of intense, often dreadful anticipation. A crime, an attack, an explosion or fire is, it seems, terrifyingly imminent.

Unsure of what I was actually watching for, it began to feel a bit sinister: had there been an attack or even a murder in the old Wembley Stadium, prior to Foster + Partners’ new design at the site, and, for whatever reason, Foster held on to security tapes of the incident? Was I about to see a stabbing or a brawl, a small riot in the corridors?

Unsure of what I was actually watching for, it began to feel a bit sinister: had there been an attack or even a murder in the old Wembley Stadium, prior to Foster + Partners’ new design at the site, and, for whatever reason, Foster held on to security tapes of the incident? Was I about to see a stabbing or a brawl, a small riot in the corridors?

More abstractly, could an architect somehow develop an attachment, a dark and unhealthy fascination, with crimes that had occurred inside a structure he or she designed—or, in this case, in a building he or she would ultimately demolish and replace?

It felt as if I was watching police evidence, sitting there, alone on a summer afternoon, waiting nervously for the depicted crime to begin.

The relationship not just between architecture and crime, but between architects and crime began to captivate me.

Of course, it didn’t take long to realize what was really happening, which was altogether less exciting but nevertheless just as fascinating: these unlabeled security tapes hidden in a cupboard at Foster + Partners hadn’t captured a crime, riot, or any other real form of suspicious activity.

Rather, the tapes had been saved in the office archive as an unusual form of architectural research: surveillance footage of people milling about near the bathrooms or walking around in small groups through the cavernous back-spaces of the old Wembley stadium would help to show how the public really used the space.

I was watching video surveillance being put to use as a form of building analysis—security tapes as a form of spatial anthropology.

[Image: Unrelated surveillance footage].

[Image: Unrelated surveillance footage].

Obsessed by this, and with surveillance in general, I went on to write an entire (unpublished) novel about surveillance in London, as well as to see the security industry—those who watch the city—as always inadvertently performing a second function.

Could security teams and surveillance cameras in fact be a privileged site for viewing, studying, and interpreting urban activity? Is architecture somehow more interesting when viewed through CCTV?

To no small extent, that strange summertime task thirteen years ago went on to inform my next book, A Burglar’s Guide to the City, which comes out in October.

The book explores how criminals tactically misuse the built environment, with a strong counter-focus on how figures of authority—police helicopter crews, FBI Special Agents, museum security supervisors, and architects—see the city in a very literal sense.

The book explores how criminals tactically misuse the built environment, with a strong counter-focus on how figures of authority—police helicopter crews, FBI Special Agents, museum security supervisors, and architects—see the city in a very literal sense.

This includes the specialty optical equipment used during night flights over the metropolis, the surveillance gear that is often deployed inside large or complex architectural structures to record “suspicious” activity, and how even the numbering systems used for different neighborhoods can affect the ability of the police to interrupt crimes that might be occurring there.

I’ll be talking about all of this stuff (and quite a bit more, including the sociological urban films of William H. Whyte, the disturbing thrill of watching real-life CCTV footage—such as the utterly strange Elisa Lam tape—and what’s really happening inside CCTV control rooms) this coming Friday night, May 8, as part of “a series about spectatorship” at UnionDocs in Brooklyn.

The event is ticketed, but stop by, if you get a chance—I believe there is a free cocktail reception afterward—and, either way, watch out for the release of A Burglar’s Guide to the City in October 2015.

[Image: “FOGBAE.TWR4” by Mike Winkelmann, 07.06.15].

[Image: “FOGBAE.TWR4” by Mike Winkelmann, 07.06.15]. [Image: “reopot seven-ten” by Mike Winkelmann, 05.04.15].

[Image: “reopot seven-ten” by Mike Winkelmann, 05.04.15]. [Image: “pxil.two” by Mike Winkelmann, 05.12.15].

[Image: “pxil.two” by Mike Winkelmann, 05.12.15]. [Image: “OB TANK” by Mike Winkelmann, 07.26.15].

[Image: “OB TANK” by Mike Winkelmann, 07.26.15]. [Image: “FRIED GOBO” by Mike Winkelmann, 07.31.15].

[Image: “FRIED GOBO” by Mike Winkelmann, 07.31.15]. [Image: “MCD 2087” by Mike Winkelmann, 08.11.15].

[Image: “MCD 2087” by Mike Winkelmann, 08.11.15]. [Image: “orangetooth gutrot” by Mike Winkelmann, 11.29.14].

[Image: “orangetooth gutrot” by Mike Winkelmann, 11.29.14]. [Image: “BOXXX-3VV” by Mike Winkelmann, 07.01.15].

[Image: “BOXXX-3VV” by Mike Winkelmann, 07.01.15].

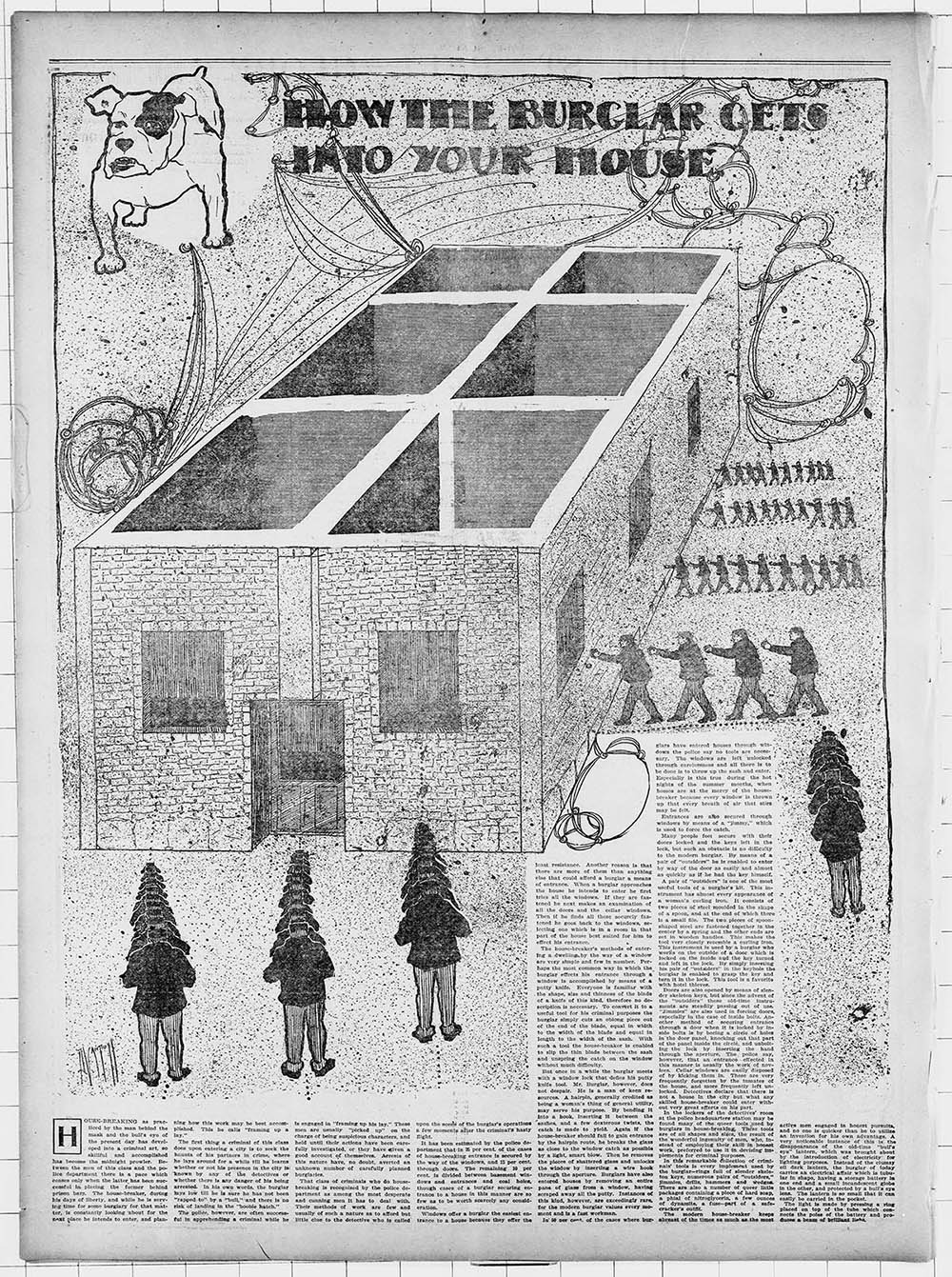

[Image: “How The Burglar Gets Into Your House” (1903), via

[Image: “How The Burglar Gets Into Your House” (1903), via  [Image: A street in Athens, via

[Image: A street in Athens, via  [Image: A totally random shot of A/C units, via

[Image: A totally random shot of A/C units, via

[Image: Horse skull via

[Image: Horse skull via  [Image: Inside the Paris

[Image: Inside the Paris

[Image: Here’s another image from the same

[Image: Here’s another image from the same

[Image: Sewn geology; photo by Matthew Cox of

[Image: Sewn geology; photo by Matthew Cox of  [Image: Lifting up fake rocks; photo by Matthew Cox of

[Image: Lifting up fake rocks; photo by Matthew Cox of

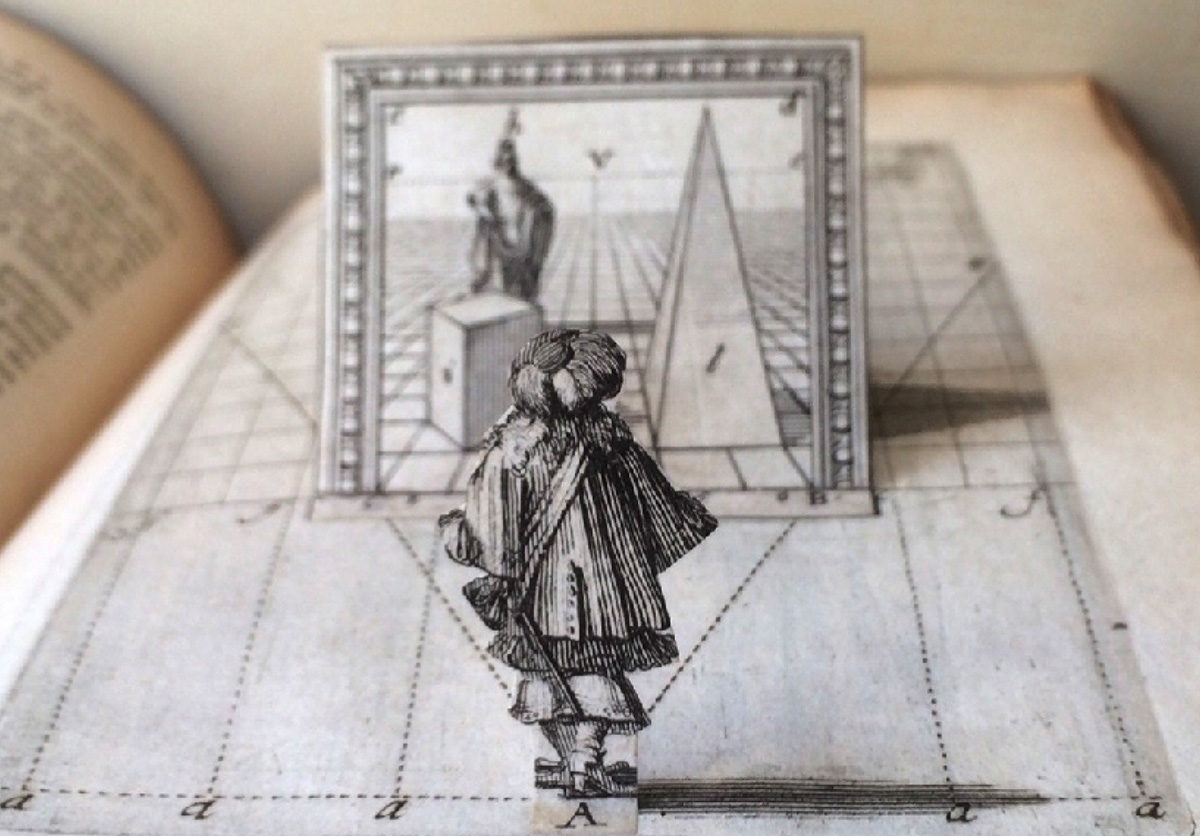

[Image: A figure and his optical context pop up from the pages of a 17th-century treatise on perspective by Abraham Bosse, defending the

[Image: A figure and his optical context pop up from the pages of a 17th-century treatise on perspective by Abraham Bosse, defending the

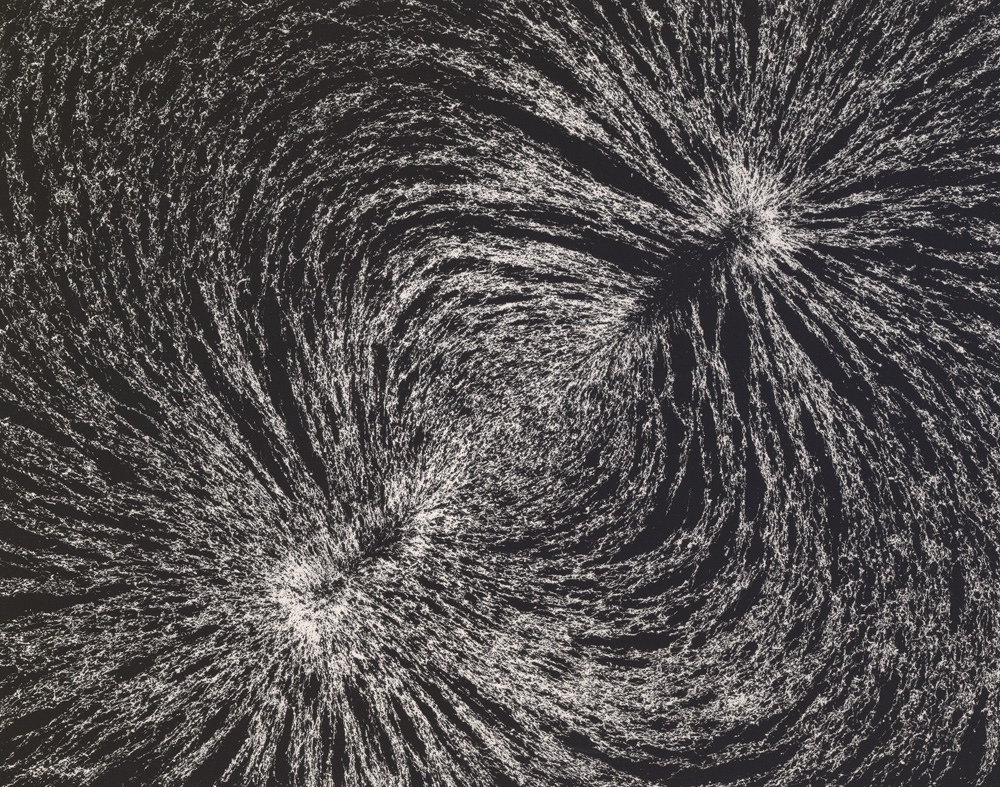

[Image:

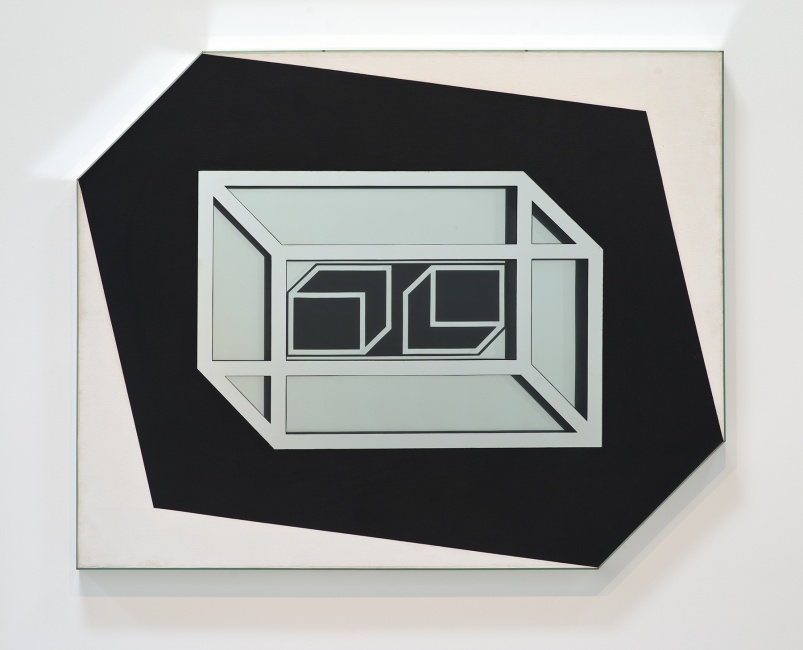

[Image:  [Image: “Untitled” by Larry Bell (1962), via the

[Image: “Untitled” by Larry Bell (1962), via the

[Image:

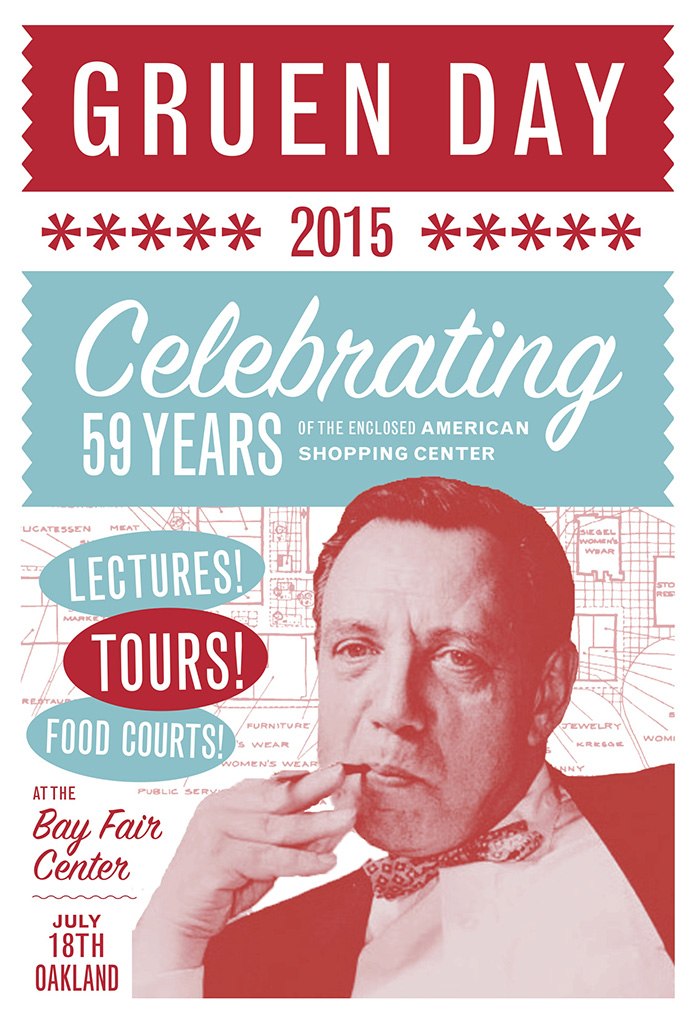

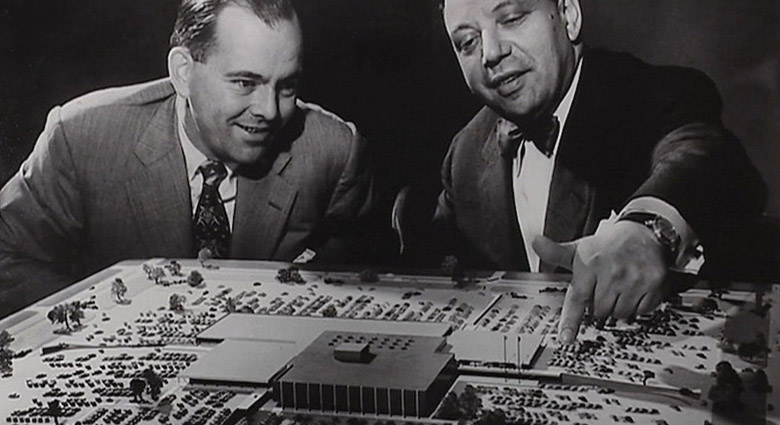

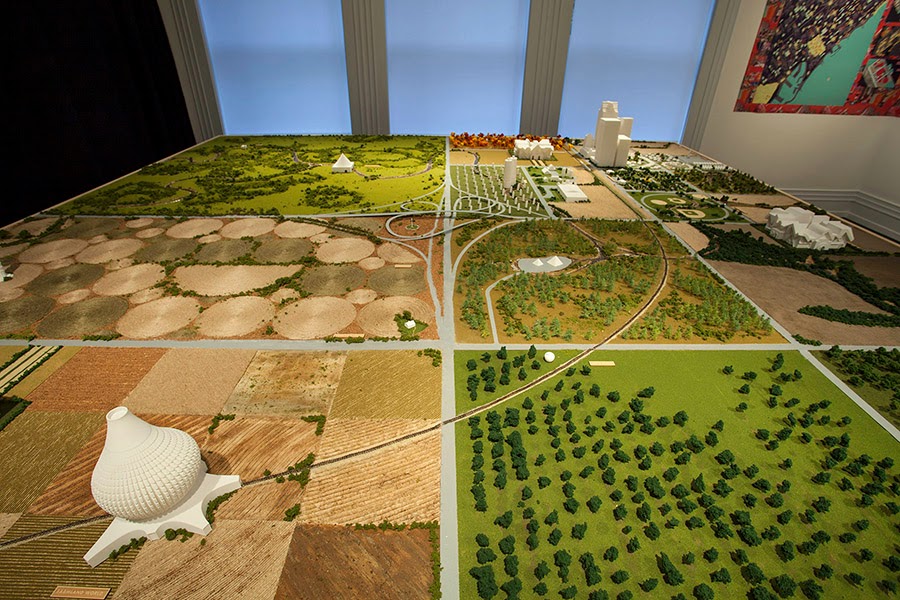

[Image:  [Image: One of many malls by Victor Gruen].

[Image: One of many malls by Victor Gruen]. [Image: Victor Gruen gestures at a mall of his making; photo originally via

[Image: Victor Gruen gestures at a mall of his making; photo originally via  [Image: Guy Debord maps psychogeographic routes through Paris; perhaps, all along, psychogeography was just a confused first-person experience of the Gruen transfer on an urban scale].

[Image: Guy Debord maps psychogeographic routes through Paris; perhaps, all along, psychogeography was just a confused first-person experience of the Gruen transfer on an urban scale].

[Image: A laser scan of the Pantheon, courtesy

[Image: A laser scan of the Pantheon, courtesy  [Image: Courtesy

[Image: Courtesy  [Image: Courtesy

[Image: Courtesy  [Image: Courtesy

[Image: Courtesy  [Image: Courtesy

[Image: Courtesy  [Image: In the ruined basements of architectural simultaneity;

[Image: In the ruined basements of architectural simultaneity;  [Image: Photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: Photo by BLDGBLOG]. Unsure of what I was actually watching for, it began to feel a bit sinister: had there been an attack or even a murder in the old Wembley Stadium, prior to Foster + Partners’

Unsure of what I was actually watching for, it began to feel a bit sinister: had there been an attack or even a murder in the old Wembley Stadium, prior to Foster + Partners’  [Image: Unrelated surveillance footage].

[Image: Unrelated surveillance footage]. The book explores how criminals tactically misuse the built environment, with a strong counter-focus on how figures of authority—police helicopter crews, FBI Special Agents, museum security supervisors, and architects—see the city in a very literal sense.

The book explores how criminals tactically misuse the built environment, with a strong counter-focus on how figures of authority—police helicopter crews, FBI Special Agents, museum security supervisors, and architects—see the city in a very literal sense.

[Image: From “Midwestern Culture Sampler” by

[Image: From “Midwestern Culture Sampler” by  [Image: From “Midwestern Culture Sampler” by

[Image: From “Midwestern Culture Sampler” by  [Image: From “Midwestern Culture Sampler” by

[Image: From “Midwestern Culture Sampler” by  [Image: From “Midwestern Culture Sampler” by

[Image: From “Midwestern Culture Sampler” by  [Image: From “Midwestern Culture Sampler” by

[Image: From “Midwestern Culture Sampler” by  [Image: A ghost of “

[Image: A ghost of “