[Image: A plane lands at Heathrow, London; photo by Simon Dawson, courtesy of Bloomberg].

[Image: A plane lands at Heathrow, London; photo by Simon Dawson, courtesy of Bloomberg].

A short article in The Economist raises the possibility that television signals in London, England, could be turned into a passive, aircraft-detecting radar system.

A system such as this “relies on existing signals, such as television and radio broadcasts, to illuminate aircraft.”

This involves using multiple antennas to listen out for signals from broadcast towers, and for reflections of those signals that have bounced off aircraft, and comparing the two. With enough number-crunching, the position, speed and direction of nearby aircraft can then be determined. Passive radar requires a lot of processing power, but because there is no need for a transmitter, it ends up being cheaper than conventional radar. It also has military benefits, because it enables a radar station to detect objects covertly, without emitting any signals of its own.

“Will soap operas and news bulletins end up helping to direct aircraft in London’s busy skies?” The Economist asks. The idea of the entirety of London becoming a passive aeronautic device, pinging both commercial aircraft and military planes, and tracking the encroachment of unmanned aerial vehicles on urban airspace, all simply by piggybacking on the everyday technology of the television set, is pretty eerie, as if living in a giant radar dish powered by late-night entertainment.

London becomes a weird new kind of camera pointed upward at secretly passing aircraft, your living room taking pictures of the sky.

It also brings to mind the so-called “wifi camera” developed way back in 2008 by Bengt Sjölén and Adam Somlai Fischer with Usman Haque. The wifi camera “takes ‘pictures’ of spaces illuminated by wifi in much the same way that a traditional camera takes pictures of spaces illuminated by visible light.”

[Image: The “wifi camera” by Bengt Sjölén and Adam Somlai Fischer with Usman Haque].

[Image: The “wifi camera” by Bengt Sjölén and Adam Somlai Fischer with Usman Haque].

You can thus create images of architectural spaces, almost like a CAT scan, based on wifi signal strength, deducing from the data things like building layout, room density, material thickness, the locations of walls, doors, windows, and more, albeit to quite a low degree of resolution.

[Image: Signal data and its spatial implications from the “wifi camera” by Bengt Sjölén and Adam Somlai Fischer with Usman Haque].

[Image: Signal data and its spatial implications from the “wifi camera” by Bengt Sjölén and Adam Somlai Fischer with Usman Haque].

“With the camera we can take real time ‘photos’ of wifi,” its developers write. “These show how our physical structures are illuminated by this particular electromagnetic phenomenon and we are even able to see the shadows that our bodies cast within such ‘hertzian’ spaces.”

It’s a kind of electromagnetic chiaroscuro that selectively and invisibly “illuminates” the built environment—until the right device or camera comes along, and all that spatial data becomes available to human view. It’s like a sixth sense of wifi, or something out of Simone Ferracina‘s project Theriomorphous Cyborg.

Here, the comparison to the London TV radar system is simply that, in both cases, already existing networks of electromagnetic signals are operationalized, so to speak, becoming inputs for a new form of visualization. You can thus take pictures of the sky, so to speak, using passive, city-wide, televisual radar, and you can scan the interiors of unknown buildings using wifi cameras tuned to routers’ electromagnetic glow.

[Image: From the “wifi camera” by Bengt Sjölén and Adam Somlai Fischer with Usman Haque].

[Image: From the “wifi camera” by Bengt Sjölén and Adam Somlai Fischer with Usman Haque].

Apropos of very little, meanwhile, and more or less dispensing with plausibility, it would be interesting to see if the same sort of thing—that is, passive radar, using pre-existing signals—could somehow be used to turn the human nervous system itself into a kind of distributed, passively electric object-detection device on an urban scale. Nervous systems of the city as sensor network: a neuro-operative technology always scanning, sometimes dreaming, interacting with itself on all scales.

An interesting symposium at Columbia University later this month looks at “

An interesting symposium at Columbia University later this month looks at “

[Image: The WWI terrain model of Messines, Belgium, in Cannock Chase, England; photo, “taken probably 1918 by Thomas Frederick Scales,” courtesy of the

[Image: The WWI terrain model of Messines, Belgium, in Cannock Chase, England; photo, “taken probably 1918 by Thomas Frederick Scales,” courtesy of the  [Image: The concrete model at Cannock Chase, including a viewing hut; photo via

[Image: The concrete model at Cannock Chase, including a viewing hut; photo via  [Image: A viewing hut for studying the model landscape; photo via

[Image: A viewing hut for studying the model landscape; photo via  [Image: The scale of the model becomes more clear in this photo, also via

[Image: The scale of the model becomes more clear in this photo, also via

[Image: The Central Park bolt, photographed by

[Image: The Central Park bolt, photographed by  [Image: A photo of Benchmark B taken by Tullio Aebischer, courtesy of

[Image: A photo of Benchmark B taken by Tullio Aebischer, courtesy of

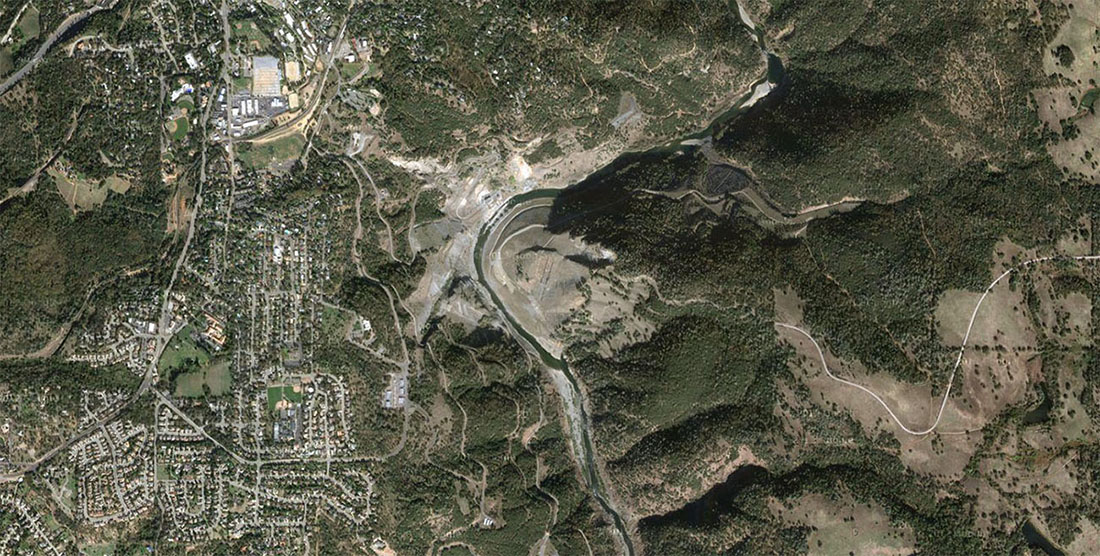

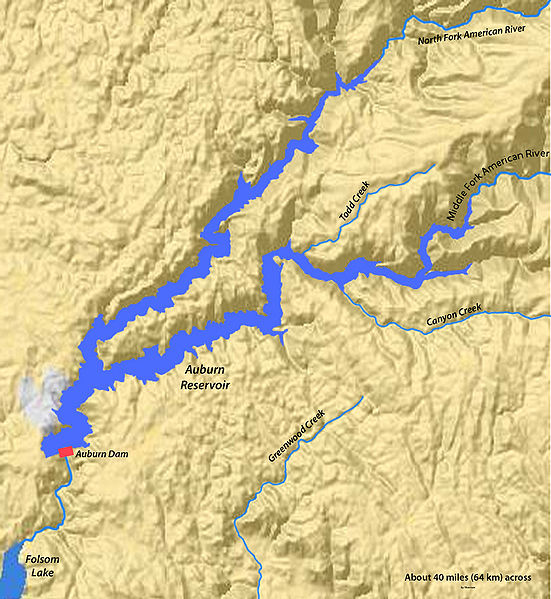

[Image: The Auburn Dam site, via

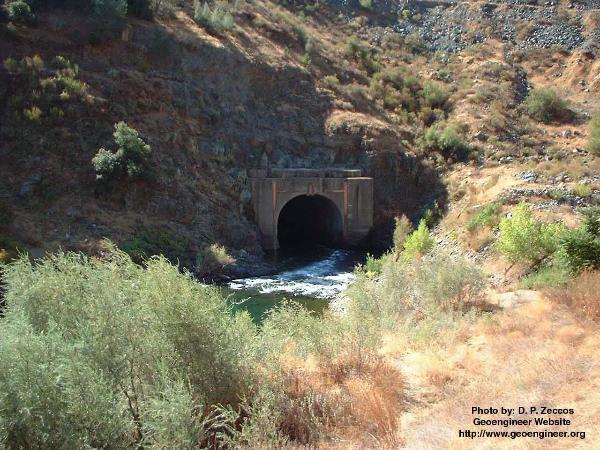

[Image: The Auburn Dam site, via  [Image: A bypass tunnel built in anticipation of the never-completed Auburn Dam; photo by D.P. Zeccos of

[Image: A bypass tunnel built in anticipation of the never-completed Auburn Dam; photo by D.P. Zeccos of  [Image: The Foresthill Bridge, via

[Image: The Foresthill Bridge, via  [Image: The expected waters of a lake that never arrived; via

[Image: The expected waters of a lake that never arrived; via

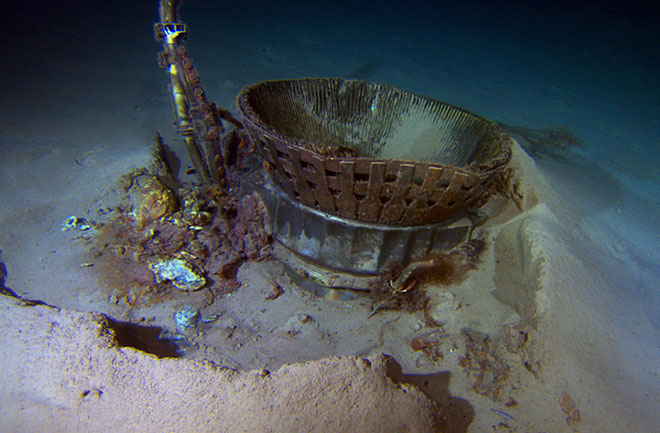

[Image: Fallen rockets at the bottom of the sea; photo by

[Image: Fallen rockets at the bottom of the sea; photo by

[Images: Photos from

[Images: Photos from  [Image: Photo from

[Image: Photo from  [Image: Photo from

[Image: Photo from

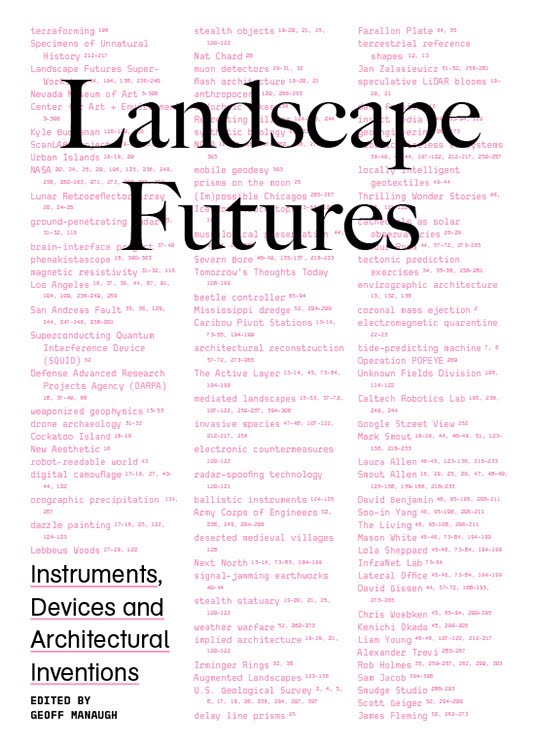

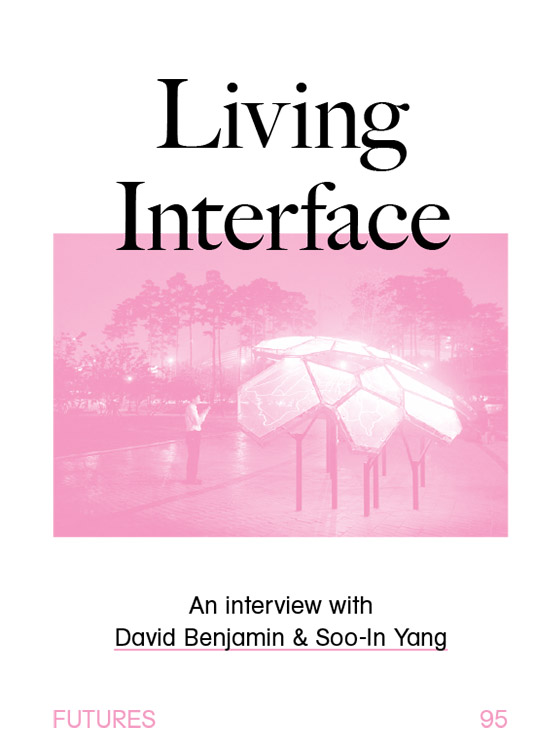

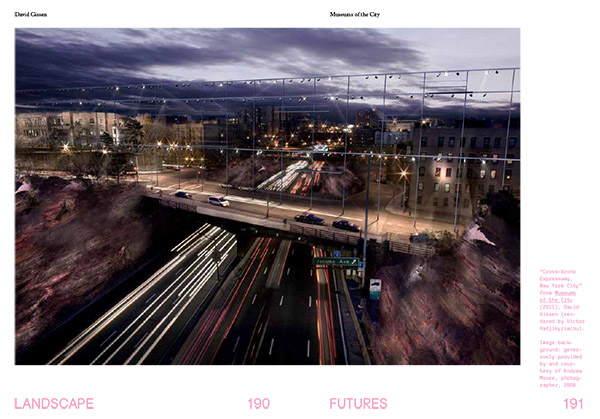

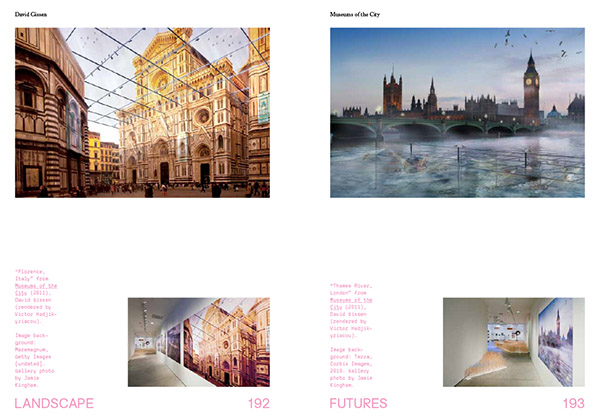

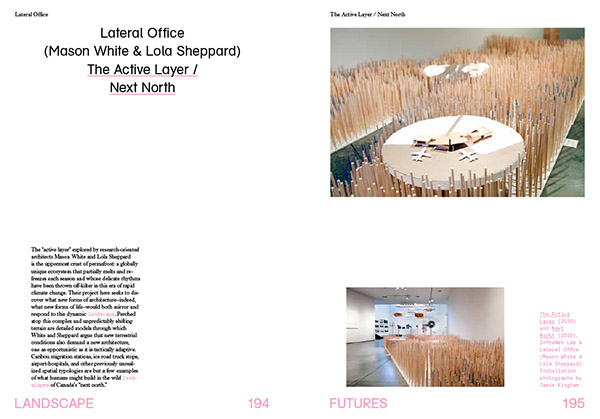

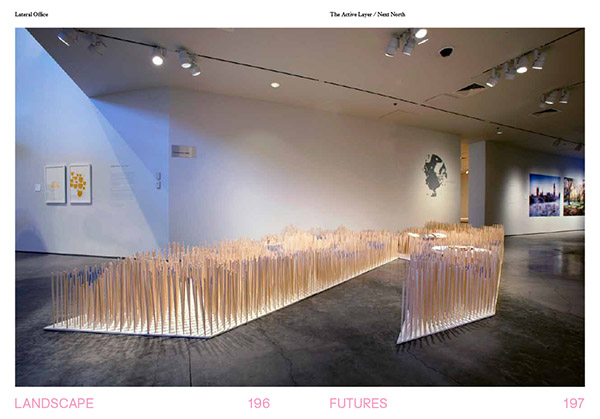

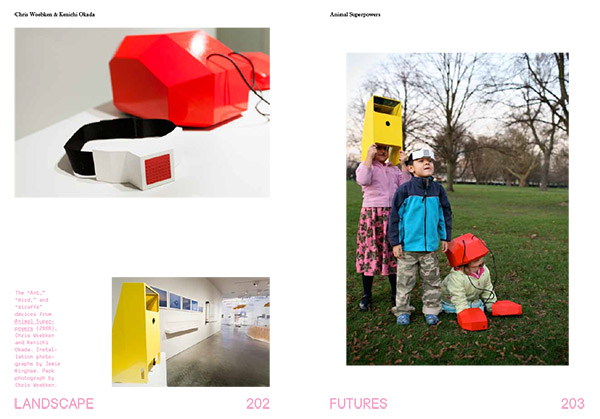

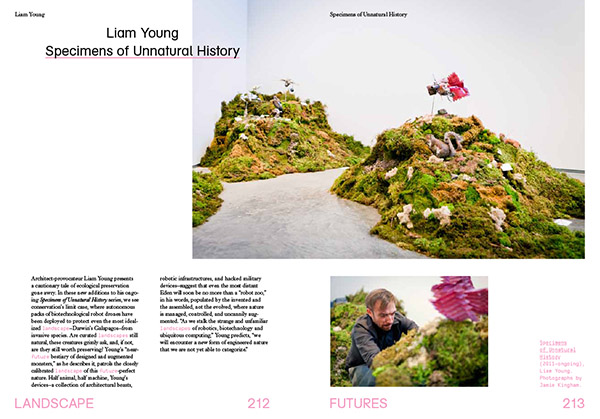

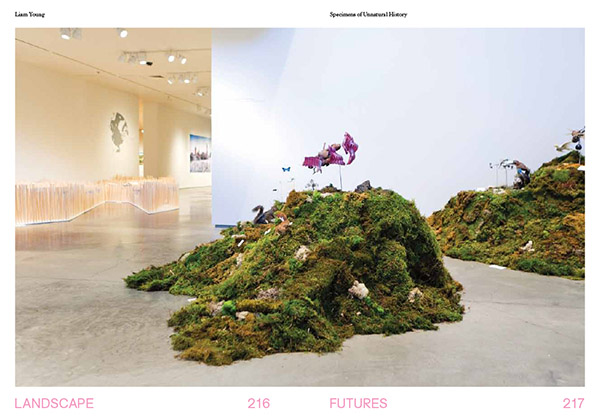

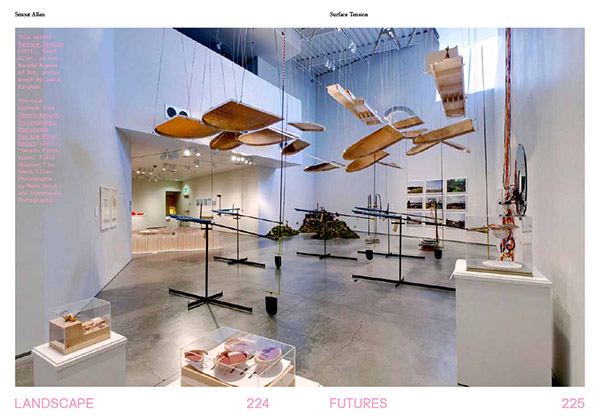

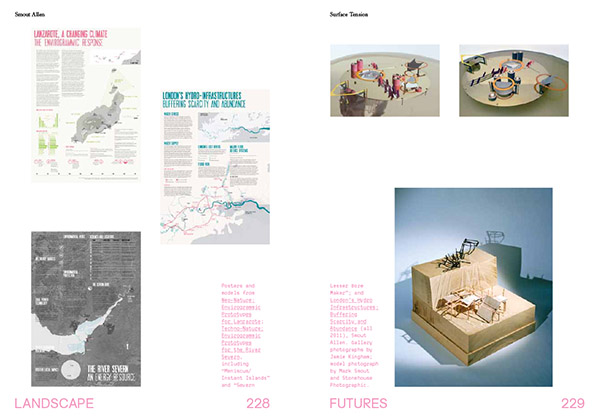

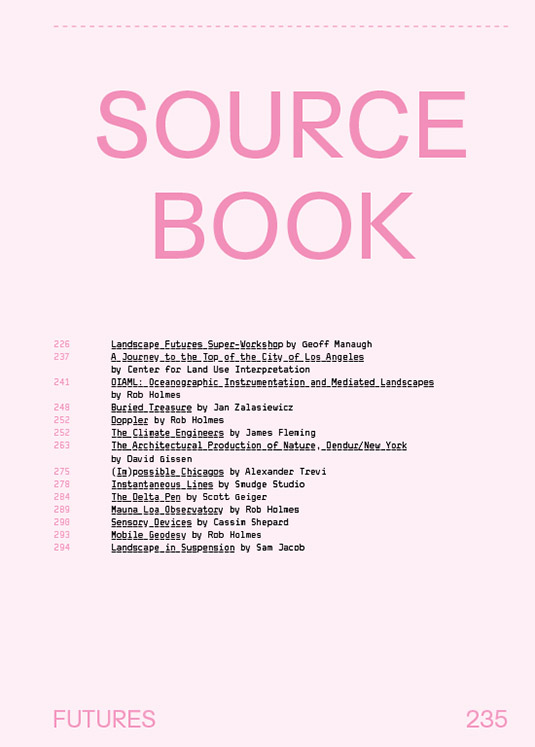

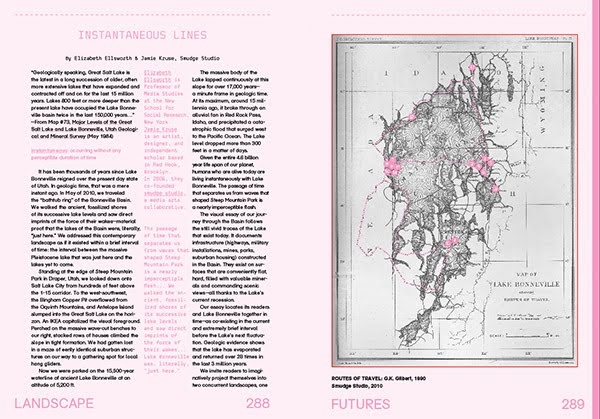

[Images: The cover of

[Images: The cover of

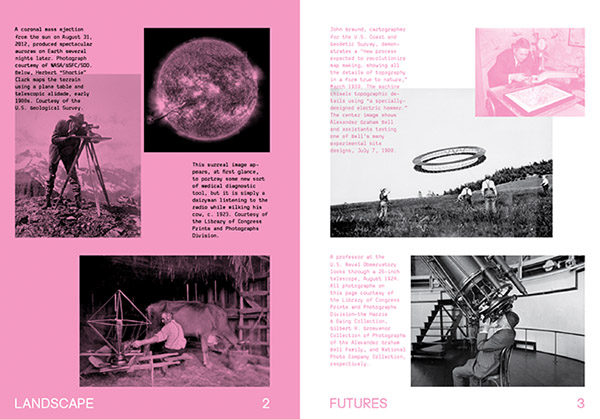

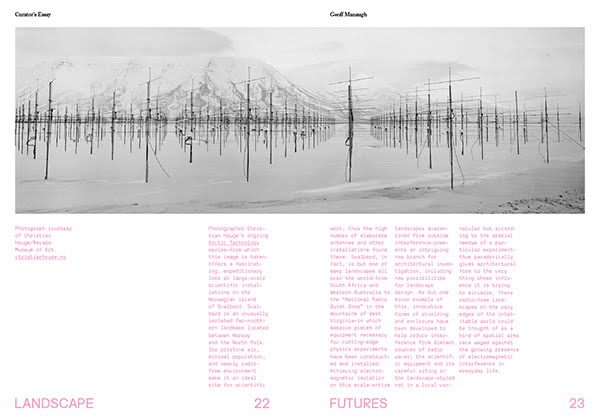

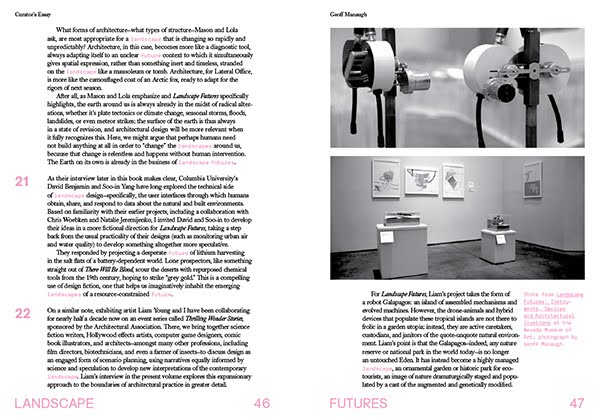

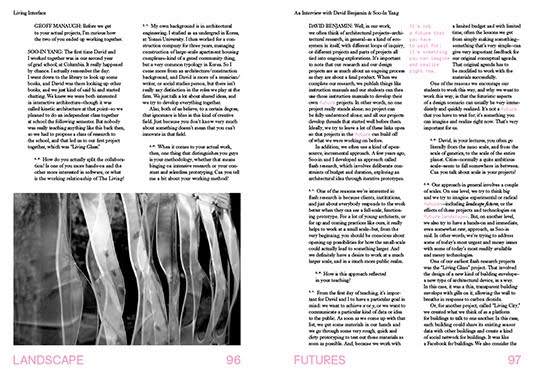

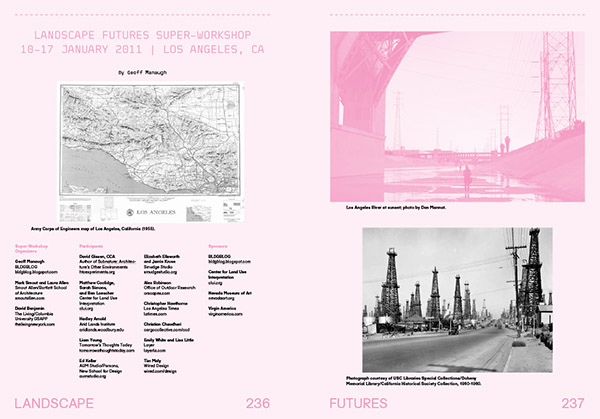

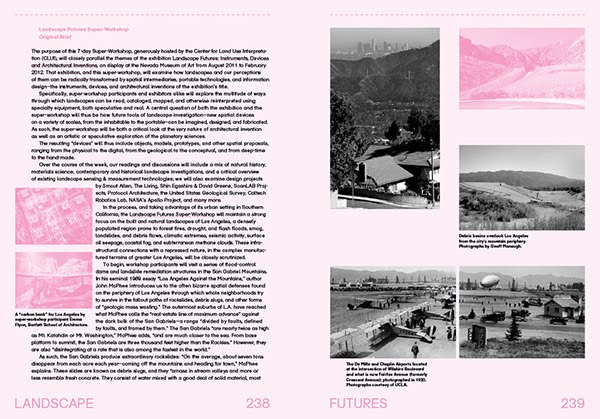

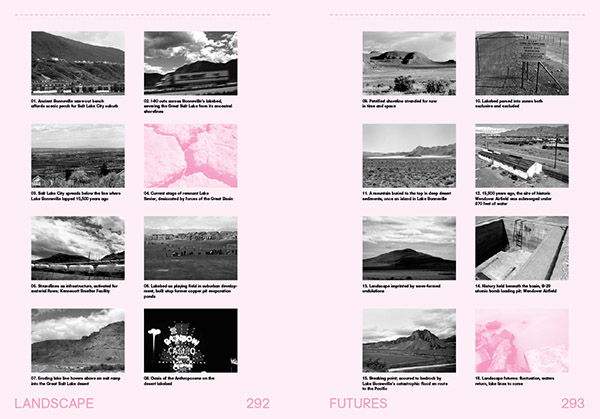

[Images: The opening spreads of

[Images: The opening spreads of

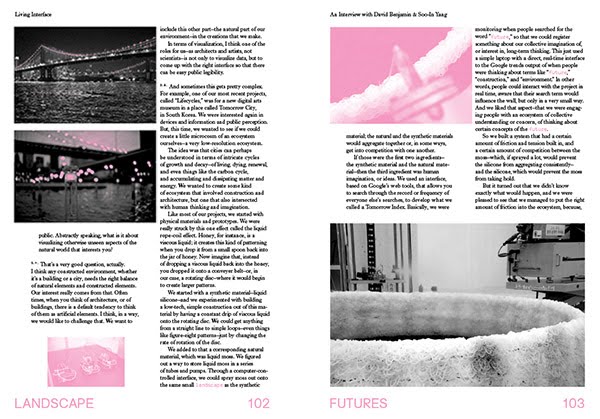

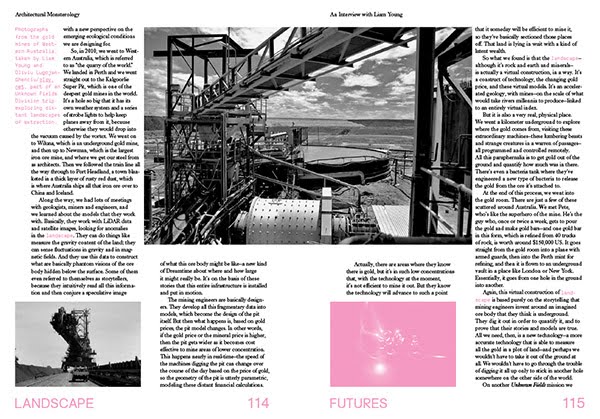

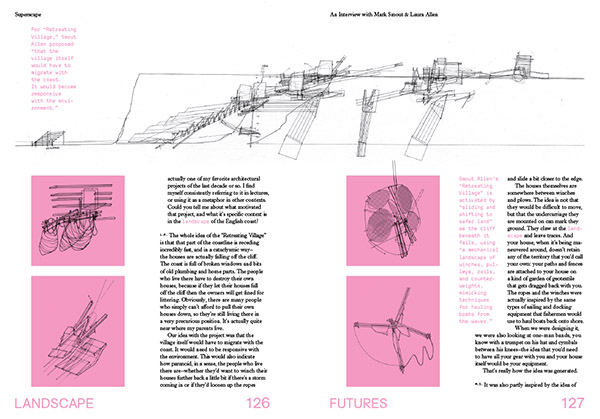

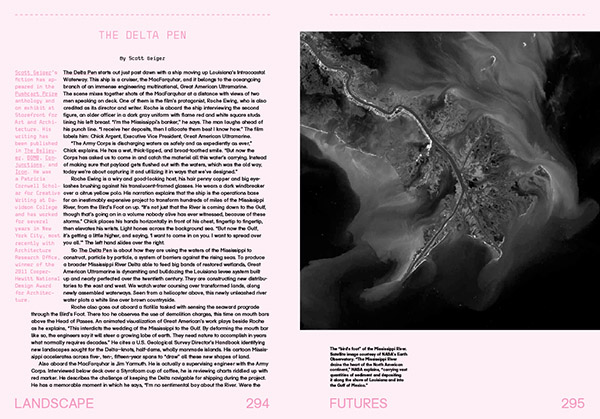

[Images: More spreads from

[Images: More spreads from

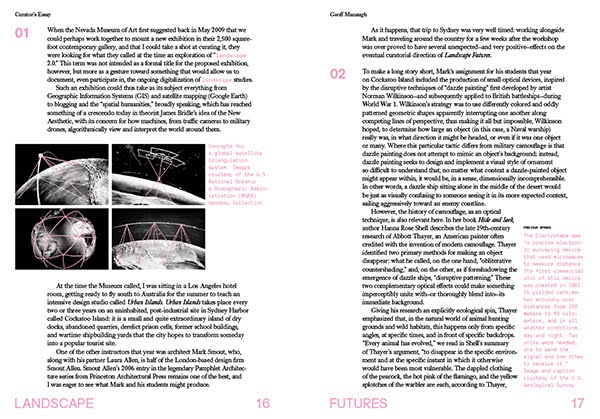

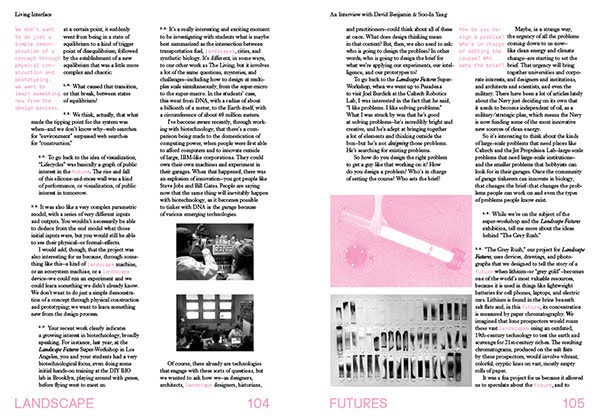

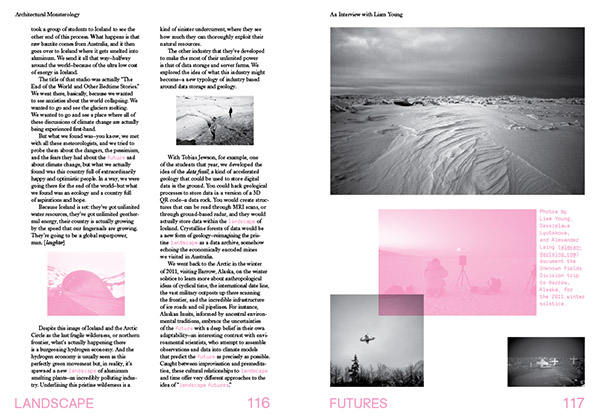

[Images: Spreads from

[Images: Spreads from

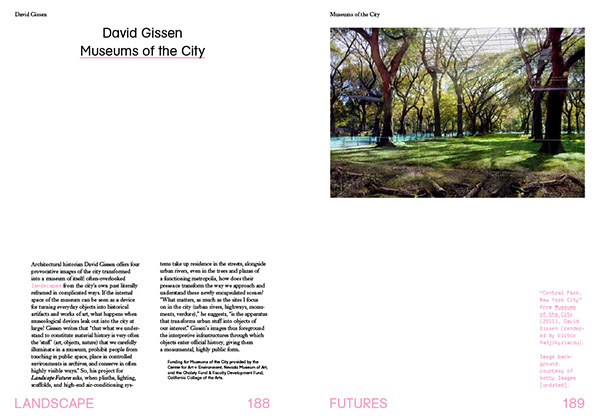

[Images: Installation shots from the Nevada Museum of Art, by Jamie Kingham and Dean Burton, including other views, from posters to renderings, from

[Images: Installation shots from the Nevada Museum of Art, by Jamie Kingham and Dean Burton, including other views, from posters to renderings, from

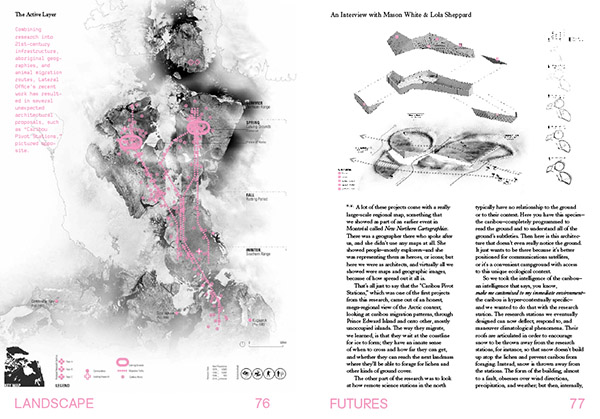

[Images: A few spreads from the Landscape Futures Sourcebook featured in

[Images: A few spreads from the Landscape Futures Sourcebook featured in

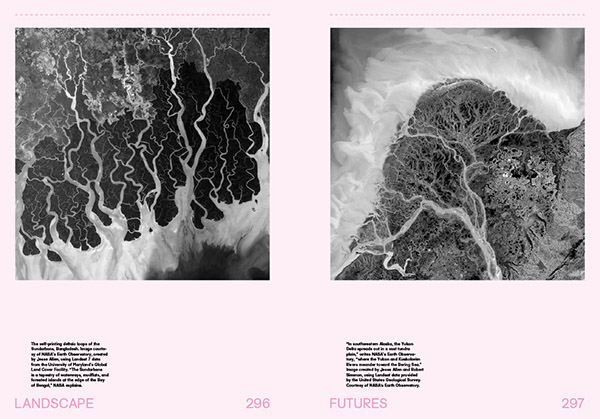

[Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Images: From “

[Images: From “ [Images: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “