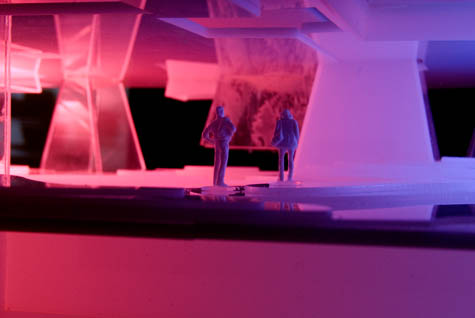

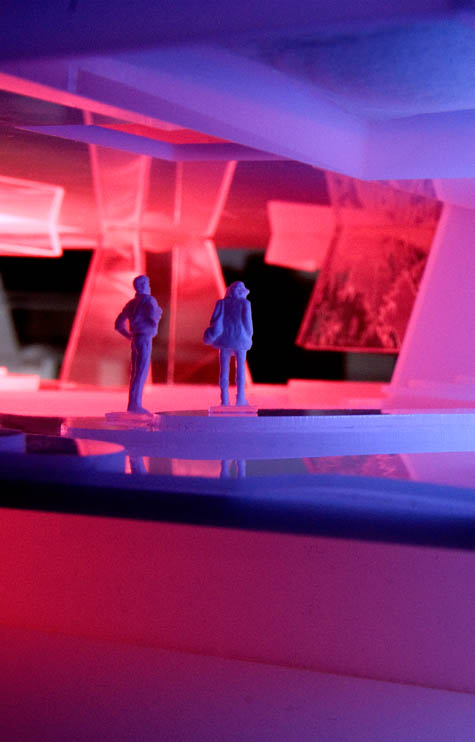

[Image: From “Change of Heart: Rethinking the Prescriptive Medical Environment” by Marina Nicollier].

[Image: From “Change of Heart: Rethinking the Prescriptive Medical Environment” by Marina Nicollier].

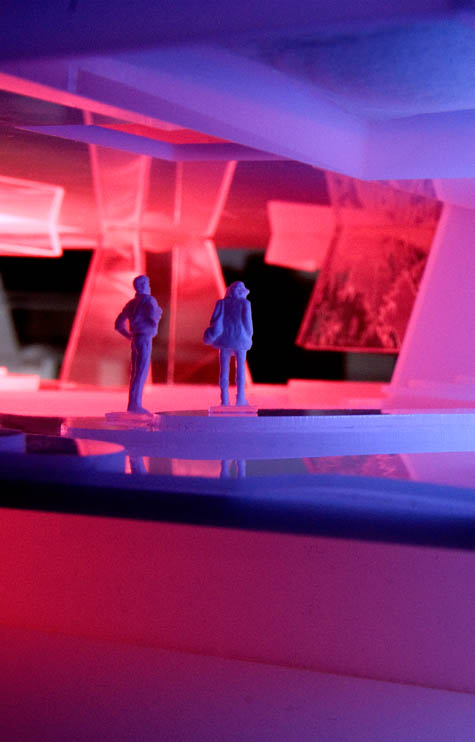

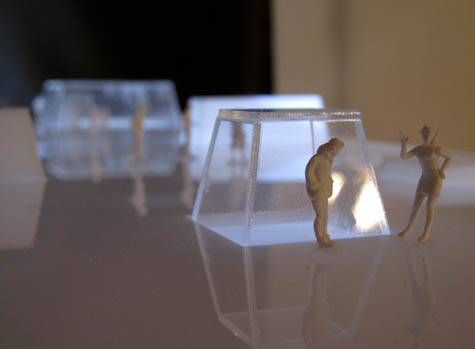

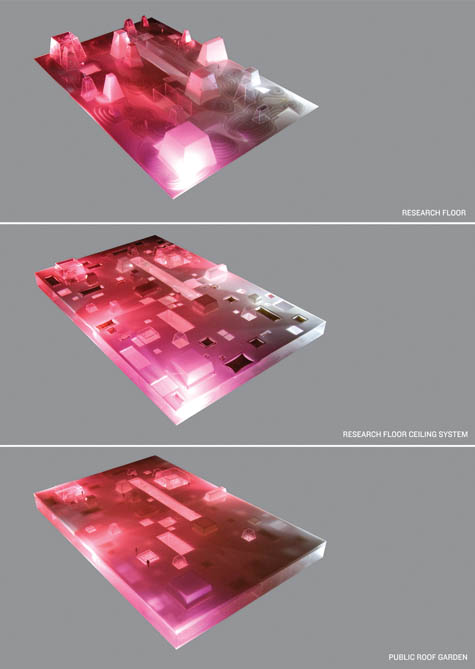

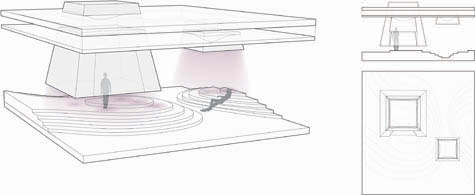

The idea that architecture might have medical effects on the people who experience it was the premise of a project by Marina Nicollier produced this year at Rice University.

In the project’s accompanying documentation, Nicollier writes that we must learn “to create spaces that provide, through their experience and material substance, enough variability in environmental effects that individual differences in reception and response can be studied and used as a part of curative regimes.”

In other words, the sensorial experience of architecture could play a role in healing – or, as Nicollier explains, “spaces themselves should act as experiential platforms that provide a broader spectrum of environmental qualities, so that we may better understand their effects on our psychology – and ultimately, on our physiology.”

[Image: From “Change of Heart” by Marina Nicollier].

[Image: From “Change of Heart” by Marina Nicollier].

From the project description:

The human body responds to its spatial and environmental surroundings in very subtle ways. Our most basic reactions to our environment can be read, essentially, in our vital signs; yet as many of these phenomena are subtle enough to be easily overlooked without some sort of monitoring device, they have been too often dismissed as fleeting emotional and sensorial effects that have little impact on our physiological system as a whole. These qualities can do much more. They can act as an architectural base for a very important body of research, expanding beyond the limited range of possibilities imposed on them by existing models of medical environments.

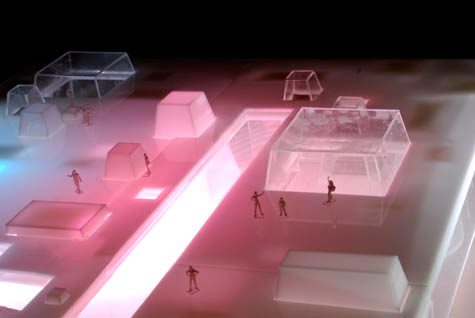

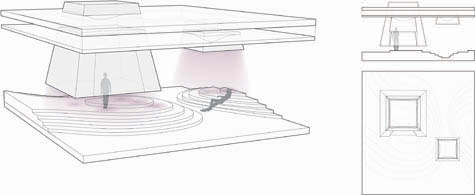

To perform a test-run for these propositions, Nicollier has designed a “cardiology research facility adjacent to two major medical institutions in Mexico City.”

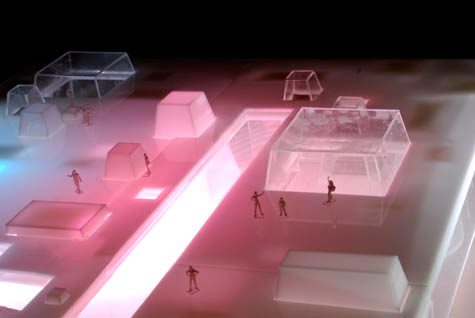

You would wander through the building, hooked up to electrocardiographs, every flutter of heart valve and sweat gland monitored by doctors from afar.

[Image: From “Change of Heart” by Marina Nicollier].

[Image: From “Change of Heart” by Marina Nicollier].

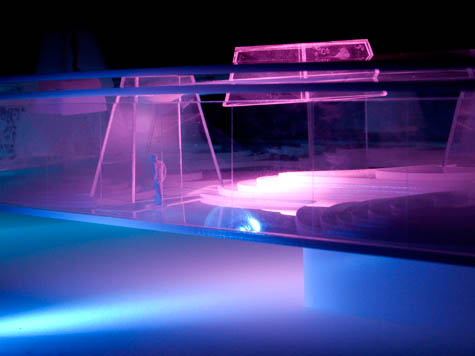

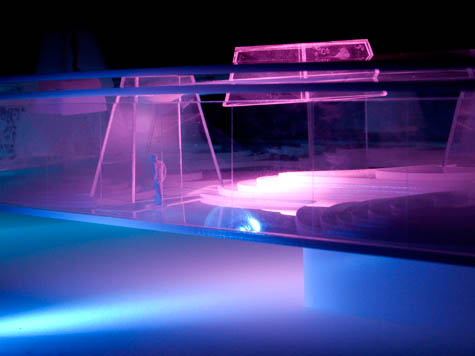

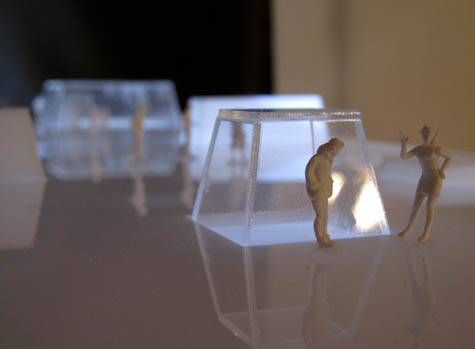

I was on Nicollier’s final thesis review the other week, where I joked that the project was like a visual combination of Barbarella and Constant’s New Babylon, by way of A Clockwork Orange – an immensely positive combination, I might add.

But that same impression strikes me today: that this is the kind of project Constant might have designed had he been more interested in the avant-garde spatial application of cardiac self-analysis.

It is the megastructure as medical cocoon, architecture designed to stimulate the human nervous system.

[Image: From “Change of Heart” by Marina Nicollier; think of it as a Foucauldian application of Winston Churchill’s famous phrase, that “We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us.” Only here, those buildings cause heart palpitations].

[Image: From “Change of Heart” by Marina Nicollier; think of it as a Foucauldian application of Winston Churchill’s famous phrase, that “We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us.” Only here, those buildings cause heart palpitations].

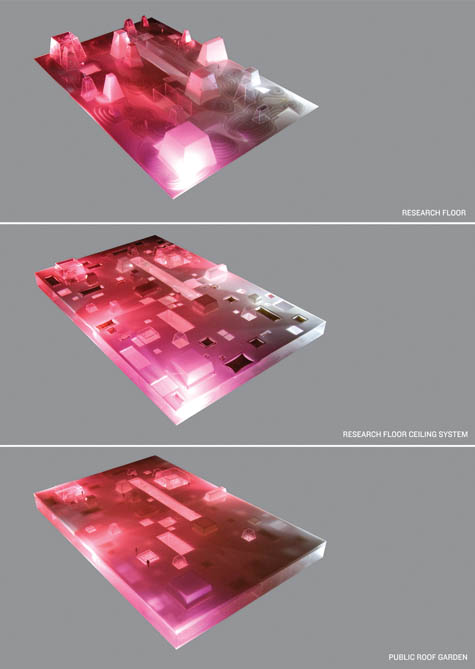

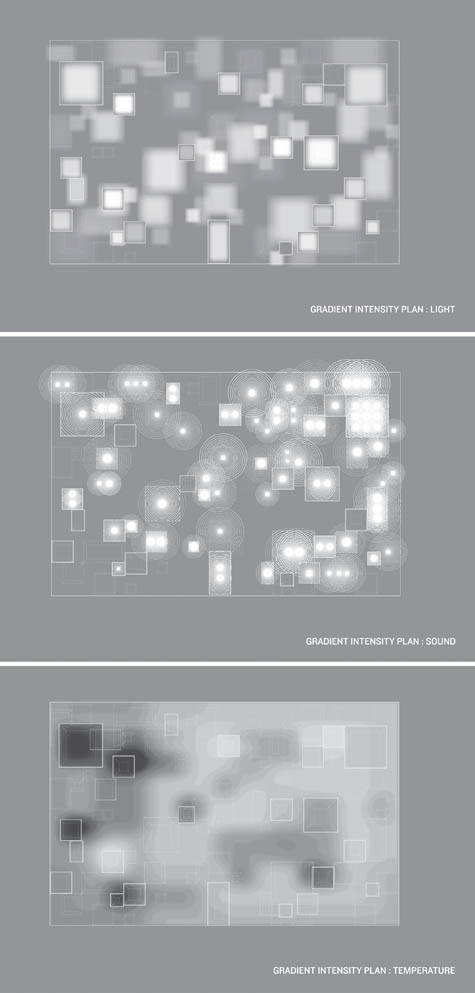

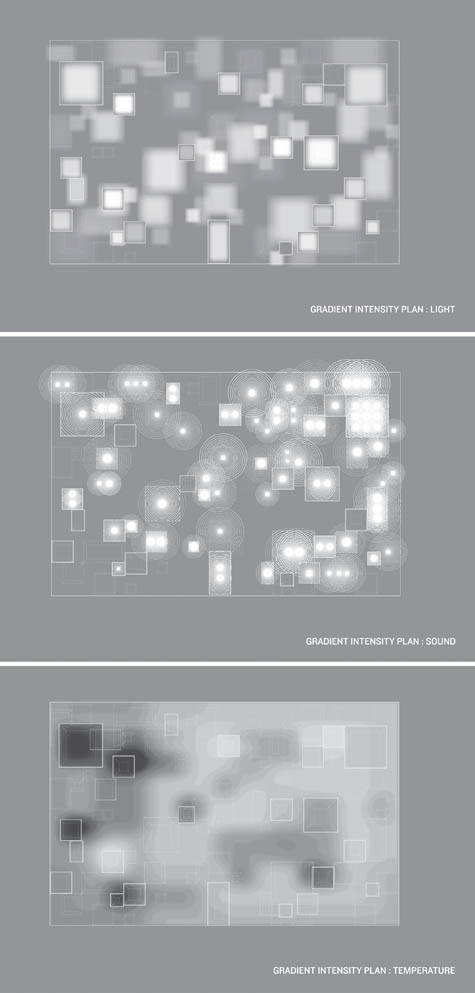

Nicollier’s cardiology research lab “relies on an experience-based design generated on a series of gradient intensities,” she writes.

She then contrasts this brilliantly with the design of modernist sanitariums, highlighting what might be called the medical origin of modern architecture:

Popular ideas about what constitutes a healthy environment gave rise to many of the components that became the formal trademarks of modernism – the flat roof was devised as a means to provide additional sunning surfaces for tubercular patients; while the deep verandas, wide private balconies, and covered corridors served as organizational tools to isolate contagious patients from the general staff.

Indeed:

Visits to these establishments were prescribed, as were the conditions and durations of the exposures themselves. Today, of course, there is ongoing research to determine how and to what extent environmental factors such as temperature, natural and artificial light, and sound affect our health, and despite there having been some interesting conclusions, it is still an area of research that requires more investigation and exploratory trials.

Then, however, in the 1950s it was discovered that tuberculosis was only treatable through the use of antibiotics, and so architectural modernism – with its wide verandahs and flat roofs – lost its medical justification, so to speak. It became just another style to be mined for a new pastiche of superficial quirks and regional variations.

[Images: From “Change of Heart” by Marina Nicollier].

[Images: From “Change of Heart” by Marina Nicollier].

Even the siting of the project, in Mexico City, plays on this development. Early modern sanitariums and “health resorts,” Nicollier writes, were designed with “specific needs regarding their site.”

Their regime of exposure to light, temperature, and clean air limited called for very particular climatic conditions falling within acceptable ranges. This is why the vast majority of these facilities were built in remote, rather idyllic locations near the coast or tucked away in alpine forests, away from any urban centers, which were considered to be too dense and dirty to be of any use for a treatment regime.

To wit, Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain.

Locating a facility like this, then, in Mexico City, a notoriously polluted megalopolis, is to suggest that architecture can counteract – that is, influentially avoid negation by – even the most invasive and unnatural of contexts. The building “supplements the environmental qualities of the city, incorporating them into its intensity gradients,” in Nicollier’s words.

[Images: From “Change of Heart” by Marina Nicollier].

[Images: From “Change of Heart” by Marina Nicollier].

But I find it almost overwhelmingly interesting to think that controlled exposure to a certain piece of architecture could actually be prescribed as a medical treatment. Viewed this way, the immersive experience of a well-designed space could actually stimulate one toward otherwise unknown medical highs and lows.

A building becomes almost pharmaceutical – or narcotic – in its level of influence over those who use it.

Could a building even become addictive?, one might ask. Could you experience something like withdrawal after going too long without experiencing it?

Could you someday receive a prescription from a doctor telling you to visit a certain building for twenty minutes everyday, because the phenomenological impact of its vaulted galleries might cure you of whatever – kidney stones, anemia, or even manic-depression? Male pattern baldness. Sexual frigidity.

Space is the treatment for the things that harm you.

[Image: From “Change of Heart” by Marina Nicollier].

[Image: From “Change of Heart” by Marina Nicollier].

During the project review, we discussed whether it might be possible for the building to act as a template or prototype for other such projects elsewhere. That is, could you produce a kind of spatial franchise in which certain combinations of color, materiality, texture, sequence, and even scent would be put to use for medical purposes? The light, sound, and temperature of the building would thus act as a general format, available to other designers in utterly dissimilar circumstances.

Perhaps it’d even be subject to regulation by the FDA and reproduced as a generic in Canada.

[Image: From “Change of Heart” by Marina Nicollier].

[Image: From “Change of Heart” by Marina Nicollier].

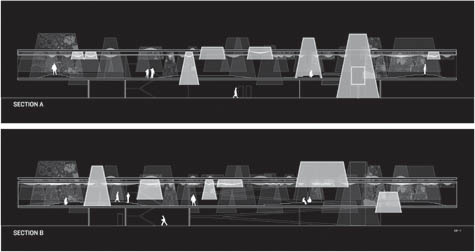

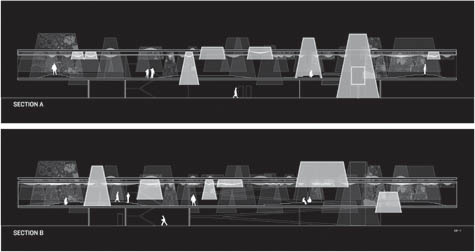

The sections, meanwhile, are beautiful in their own way –

[Images: From “Change of Heart” by Marina Nicollier].

[Images: From “Change of Heart” by Marina Nicollier].

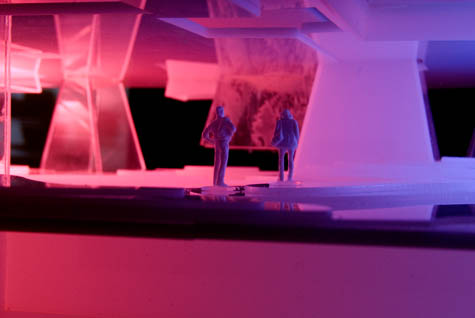

– though I’m unashamedly a fan of the semi-psychedelic mood lighting of the actual models.

[Image: From “Change of Heart” by Marina Nicollier].

[Image: From “Change of Heart” by Marina Nicollier].

To read a complete description of the project and see larger images, check out this Flickr set of the project.

(“Change of Heart” was produced at Rice University under the supervision of Dawn Finley, Eva Franch Gilabert, Farès el-Dahdah, and Albert Pope).

[Image: A moldy sofa, otherwise unrelated to this post, photographed by Flickr user melinnis].

[Image: A moldy sofa, otherwise unrelated to this post, photographed by Flickr user melinnis]. [Image: The revised tower, via the

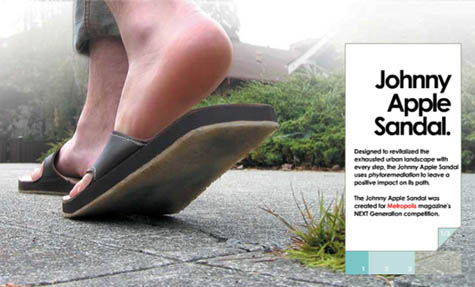

[Image: The revised tower, via the  [Image: “Johnny Apple Sandal” by

[Image: “Johnny Apple Sandal” by  [Image: By David Gray for

[Image: By David Gray for  [Image: By Andy Wong for the Associated Press, via

[Image: By Andy Wong for the Associated Press, via  [Image: “Daechi Dong,” a photo by

[Image: “Daechi Dong,” a photo by

[Images: “Howon Dong” and “Sinbong Dong 2,” photos by

[Images: “Howon Dong” and “Sinbong Dong 2,” photos by

[Images: “Samsung Dong” and “Uman Dong,” photos by

[Images: “Samsung Dong” and “Uman Dong,” photos by  [Image: “Sindorim Dong” by

[Image: “Sindorim Dong” by

[Images: “Jangan Dong” and “Sinbong Dong,” photos by

[Images: “Jangan Dong” and “Sinbong Dong,” photos by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: From Chris Bodle’s

[Image: From Chris Bodle’s  [Image: From Chris Bodle’s

[Image: From Chris Bodle’s  [Image: Logo by

[Image: Logo by  [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: The Iska Vagu stream near Hyderabad, India. “Indian factories that make lifesaving drugs swallowed by millions worldwide are creating the worst pharmaceutical pollution ever measured,”

[Image: The Iska Vagu stream near Hyderabad, India. “Indian factories that make lifesaving drugs swallowed by millions worldwide are creating the worst pharmaceutical pollution ever measured,”