In his book Terra Antarctica – previously discussed here – author William L. Fox takes us to an Antarctic field research city called, appropriately, Pole. This geodesic-domed instant city is built on Beardmore glacier – which, Fox writes, is “a ferocious uphill maze riven with thousands of crevasses,” where high-speed winds are caused not by weather in any real sense of the word, but by “dense cold air sliding off the interior toward the coast via gravity.”

[Image: “Beardmore Glacier, slicing its way through the Transantarctic Mountains.” Via Glaciers of the World].

[Image: “Beardmore Glacier, slicing its way through the Transantarctic Mountains.” Via Glaciers of the World].

Pole itself is an agglomeration of Jamesway huts, “corrugated metal tunnels” slowly blown over with snow, and the massive geodesic dome for which the city has become most famous. The dome is not precisely architectural, on the other hand: “The station is more like a raft floating on a very slow moving sea of ice two miles deep than a traditional building footed on the ground.”

It is structure imposed upon frozen hydrology: the insufficiently modeled glacial surface undergoes complicated deformations, thwarting all attempts to achieve longterm stability. It’s a kind of ice seismology.

In any case, one of the most interesting aspects of the whole thing is actually found below the city, in Pole’s so-called “sewage bulbs.” To quote at length:

Water for the station is derived by inserting a heating element – which looks like a brass plumb bob 12 feet in diameter – 150 feet into the ice and then pumping out the meltwater. After a sphere has been hollowed out over several years, creating a bulb that bottoms out 500 feet below the surface, they move to a new area, using the old bulb to store up to a million gallons of sewage, which freezes in place – sort of. The catch is, the ice cap is moving northward toward the coast (and Rio de Janeiro) at a rate of about an inch a day, or 33 feet per year. That movement means that the tunnels are steadily compressing; as a result, they have to be reamed out every few years to maintain room for the insulated water and sewage pipes. Because each sewage bulb fills up in five to six years, they’re hoping – based on the length of the tunnel and the number of bulbs they can create off it (perhaps even seven or eight) – this project will have a forty-year lifespan. Ultimately, in about the year A.D. 120,000, the whole mess should drop off into the ocean.

Rather than sewage bulbs, however, why not use the same technique to melt spherical chambers of a new, inverted cathedral one thousand feet below the Antarctic surface, a void-maze of linked naves and side-chapels moving slowly down-valley with the glacier…? Rather than a church organ, for instance, you’d have the natural music of the ice itself, a glacial moan of augmented terrestrial pressures. The whole system could be sanctified, renamed Vatican 2, and new saints of ice could win Bible study grants to reside there, in thick parkas, reading Thomas à Kempis over three-month stays. A new religious movement – called glacial mysticism – soon results.

Unearthly, geometric, the voids of this new ecumenical church might even burn reflectively inside with the aurora australis.

[Image: The aurora borealis – yes, the Northern, not Southern, Lights. Sorry. Via NASA].

[Image: The aurora borealis – yes, the Northern, not Southern, Lights. Sorry. Via NASA].

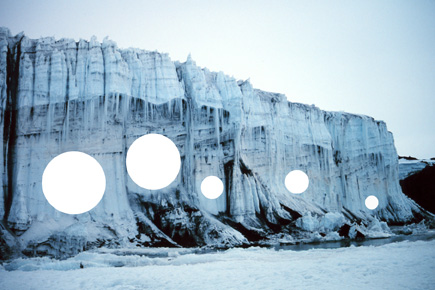

A hundred thousand years later, the cathedral reaches the sea, where its vast internal voids are broken open and revealed in the glacial cliff face. Sections of nave and pulpit can be found floating in the water, sculpted rims of prayer-domes drifting north in the smooth surfaces of icebergs. Here and there a complete chapel; elsewhere a crypt, its tombs’ chiseled inscriptions melting slowly in the sun.

Some future group of Argentine architectural students will then take a field-trip there, sketchbooks in hand, and they’ll spend two weeks back-mapping the precisely measured structure to its original, geometric clarity.

[Image: The BLDGBLOG glacial cathedral, adapted from this photo, ©Michael Van Woert/NOAA NESDIS/ORA].

[Image: The BLDGBLOG glacial cathedral, adapted from this photo, ©Michael Van Woert/NOAA NESDIS/ORA].

Another hundred thousand years later, there’s no trace of the cathedral at all.

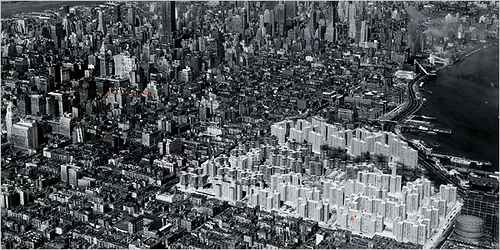

[Image: Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village, from the

[Image: Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village, from the  [Image: ©Frederic Chaubin, Wedding Palace (Tbilisi, Georgia, 1985). Last month,

[Image: ©Frederic Chaubin, Wedding Palace (Tbilisi, Georgia, 1985). Last month,

The Archipelago was first published in

The Archipelago was first published in

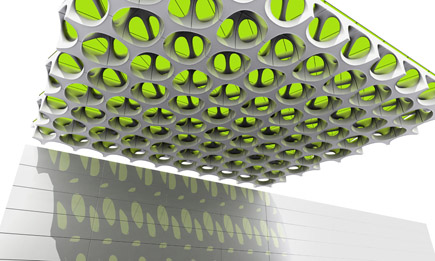

[Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image: