[Image: The Mole Man’s house in Hackney, via Wikipedia].

[Image: The Mole Man’s house in Hackney, via Wikipedia].

As most anyone who’s seen me give a talk over the past few years will know, I have a tendency to over-enthuse about the DIY subterranean excavations of William Lyttle, aka the Mole Man of Hackney.

Lyttle—who once quipped that “tunneling is something that should be talked about without panicking”—became internationally known for the expansive network of tunnels he dug under his East London house. The tunnels eventually became so numerous that the sidewalk in front of his house collapsed, neighbors began to joke that Lyttle might soon “come tunnelling up through the kitchen floor,” and, as a surveyor ominously relayed to an English court, “there is movement in the ground.”

From the Guardian, originally reported back in 2006:

No one knows how far the the network of burrows underneath 75-year-old William Lyttle’s house stretch. But according to the council, which used ultrasound scanners to ascertain the extent of the problem, almost half a century of nibbling dirt with a shovel and homemade pulley has hollowed out a web of tunnels and caverns, some 8m (26ft) deep, spreading up to 20m in every direction from his house.

What did he store down there? After Lyttle was forced from the house for safety reasons, inspectors discovered “skiploads of junk including the wrecks of four Renault 4 cars, a boat, scrap metal, old baths, fridges and dozens of TV sets stashed in the tunnels.”

But now the late Mole Man’s home is for sale.

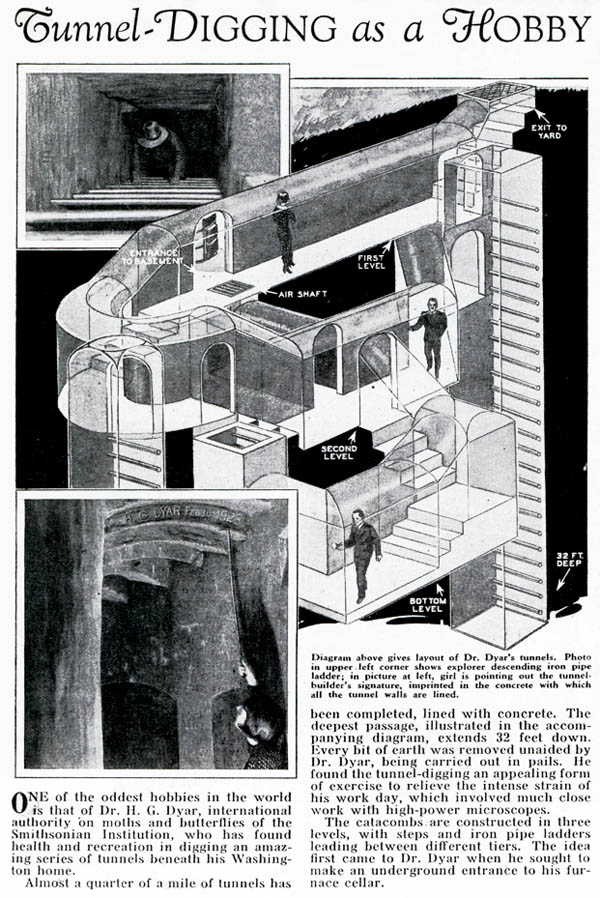

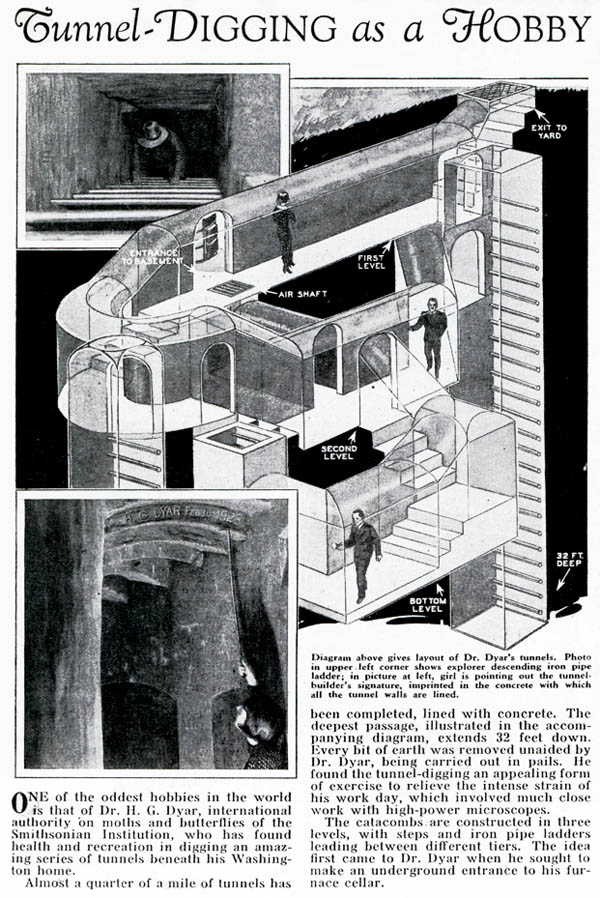

[Image: An earlier Mole Man: Tunnel-Digging as a Hobby].

[Image: An earlier Mole Man: Tunnel-Digging as a Hobby].

Alas, “most of the tunnels have been filled in” with concrete, and the house itself is all but certain to be torn down by its future owner, but I like to think that maybe, just maybe, some strange museum of subterranea could open up there, in some parallel world, complete with guided tours of the excavations below and how-to evening classes exploring the future of amateur home excavation. Curatorial residencies are offered every summer, and underground tent cities pop-up beneath the surface of the capital city, lit by candles or klieg lights, spreading out a bit more each season.

Briefly, I’m reminded of a scene from Georges Perec’s novel Life: A User’s Manual, in which a character named Emilio Grifalconi discovers “the remains of a table” that he hopes to salvage for use in his own home. “Its oval top, wonderfully inlaid with mother-of-pearl, was exceptionally well preserved,” Perec explains, “but its base, a massive, spindle-shaped column of grained wood, turned out to be completely worm-eaten. The worms had done their work in covert, subterranean fashion, creating innumerable ducts and microscopic channels now filled with pulverized wood. No sign of this insidious labor showed on the surface.”

Grifalconi soon realizes that “the only way of preserving the original base—hollowed out as it was, it could no longer suport the weight of the top—was to reinforce it from within; so once he had completely emptied the canals of the their wood dust by suction, he set about injecting them with an almost liquid mixture of lead, alum and asbestos fiber. The operation was successful; but it quickly became apparent that, even thus strengthened, the base was too weak”—and the table would thus have to be discarded.

At which point, Grifalconi has an idea: he begins “dissolving what was left of the original wood” in the table’s base in order to “disclose the fabulous arborescence within, this exact record of the worms’ life inside the wooden mass: a static, mineral accumulation of all the movements that had constituted their blind existence, their undeviating single-mindedness, their obsinate itineraries; the faithful materialization of all they had eaten and digested as they forced from their dense surroundings the invisible elements needed for their survival, the explicit, visible, immeasurably disturbing image of the endless progressions that had reduced the hardest of woods to an impalpable network of crumbling galleries.”

Somewhere beneath a new building in East London, then, some handful of years from now, the Mole Man’s “fabulous arborescence” will still be down there, a vast and twisting concrete object preserved in all its tentacular sprawl, like some unacknowledged tribute to Rachel Whiteread: a buried and elephantine sculpture that shows up on radar scans of the neighborhood, recording for all posterity “the endless progressions” of Lyttle’s eccentric and mysterious life.

(Via @SubBrit. Earlier adventures in real estate on BLDGBLOG: Buy a Prison, Buy a Tube Station, Buy an Archipelago, Buy a Map, Buy a Torpedo-Testing Facility, Buy a Silk Mill, Buy a Fort, Buy a Church,).

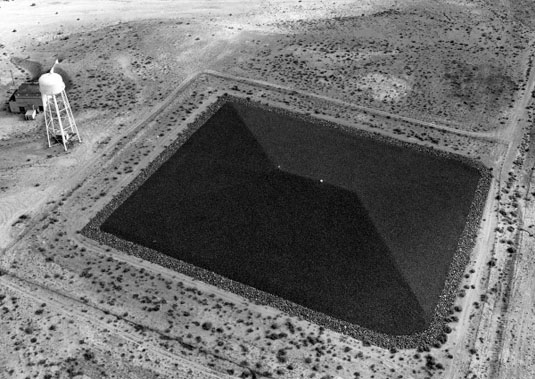

[Image: A “disposal cell,” also visible on Google Maps, courtesy of CLUI].

[Image: A “disposal cell,” also visible on Google Maps, courtesy of CLUI].

[Image: The tools and props of surveying; courtesy of the

[Image: The tools and props of surveying; courtesy of the  [Image: Understanding landscapes by way of strange devices; courtesy of the

[Image: Understanding landscapes by way of strange devices; courtesy of the  [Image: The Venue tripods, universal mounts for interchangeable devices; designed by Chris Woebken].

[Image: The Venue tripods, universal mounts for interchangeable devices; designed by Chris Woebken]. [Image: The Venue box takes shape, custom-designed by

[Image: The Venue box takes shape, custom-designed by

[Image: The Buncefield explosion, via the

[Image: The Buncefield explosion, via the

[Image: The Mole Man’s house in Hackney, via

[Image: The Mole Man’s house in Hackney, via  [Image: An earlier Mole Man:

[Image: An earlier Mole Man:

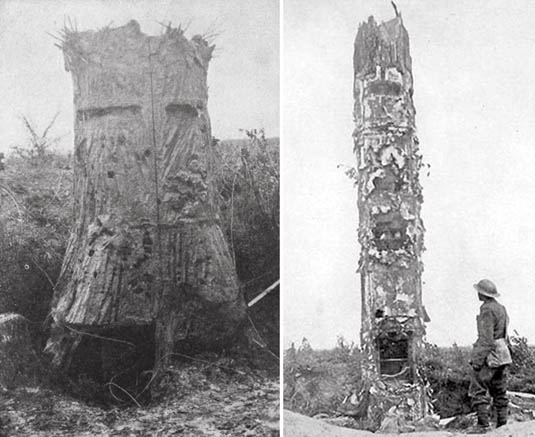

[Image: An exemplary “Observation Post Tree” via the

[Image: An exemplary “Observation Post Tree” via the  [Image: O.P. Trees].

[Image: O.P. Trees].

[Image: Prisons for sale; photo by

[Image: Prisons for sale; photo by

[Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “

[Image: Art by

[Image: Art by  [Image: The

[Image: The

[Image:

[Image:  [Image: Ole Scheeren’s “

[Image: Ole Scheeren’s “

Like the

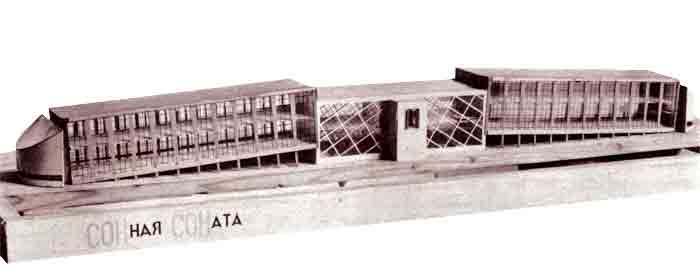

Like the  [Image: Konstantin Melnikov’s “

[Image: Konstantin Melnikov’s “

[Image: L.A.’s original subway, now walled-off beneath downtown; photo by

[Image: L.A.’s original subway, now walled-off beneath downtown; photo by  [Image:Photo by

[Image:Photo by  [Image: A walled-up sign announces, “TRAINS”; photo by

[Image: A walled-up sign announces, “TRAINS”; photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by