The previous post, looking at the possibility of an object that could be carved, whittled, and reduced infinitely, each section revealing new, fractal details, reminded me of two short films we showed several years ago at the Silver Lake Film Festival, both by architect Bradford Watson.

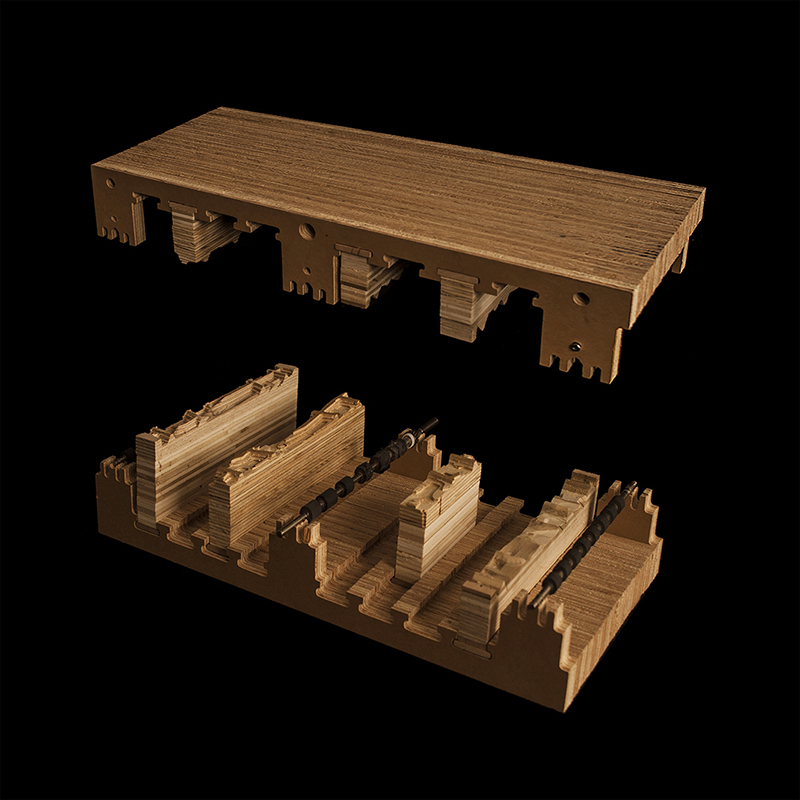

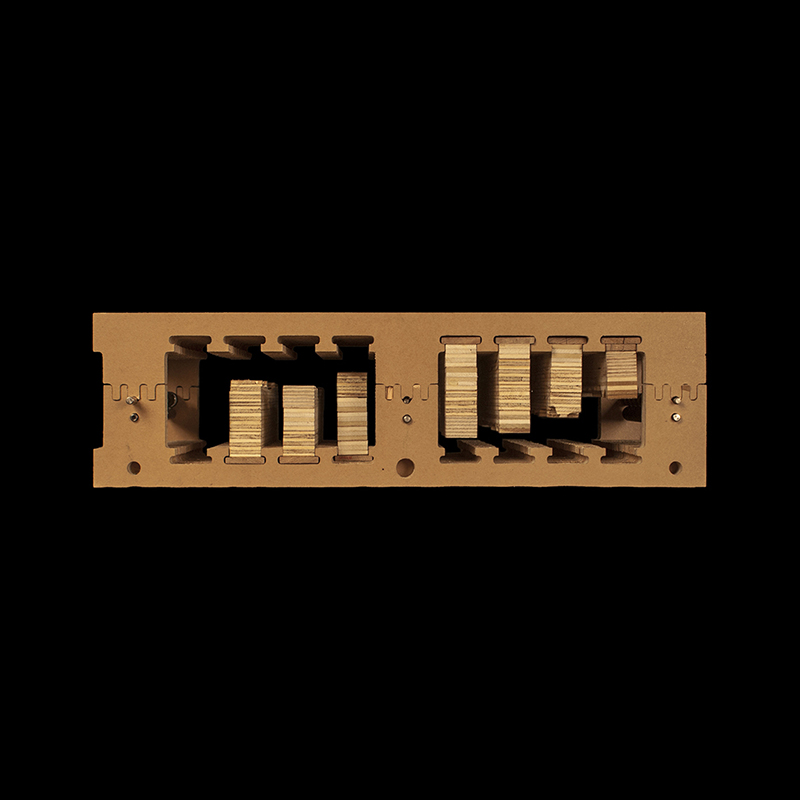

An over-literal description doesn’t really do Watson’s work justice. In the first one, embedded below, you are looking at nothing more complicated than a series of 768 sectional cuts taken through a 96-inch 2×4, after which the resulting wooden blocks were used to make black & white prints, and the prints were then played in sequence, like a flipbook. In the second film, you’re watching something even more straight-forward, which is a “matched pair” of 2x4s that have been cut down, photographed, and filmed in order until there is no more 2×4 left to cut through.

And that’s it.

But they’re both well worth watching, if for no other reason than the sensation they give, in the first video’s case, of flying forward through space, complete with weird astronomical bursts of energy shooting diagonally and comet-like across the wood grain (for example, the moment captured at 00:09-00:10).

In the second video, below, the wood seems to mimic the rings of Saturn, a planetary concentricity occasionally crossed and streaked by foreign objects (for example, see the event at 00:18-00:19 or rewatch the weird knotted prominence, like a solar storm in wood, that appears at 00:51-00:59).

It’s as if the wood itself all along had been filming the sun somehow, capturing that solar exposure in wood and documenting the star whose radiation and light had helped it to grow in the first place—as if, when you slice down into something as simple as a 2×4 normally used to construct suburban houses, you can find films of the universe, weird short loops of the skies exploding, splintered by comets and solar storms.

In fact, I’m reminded of a quotation I’ve always liked, from a book called Earth’s Magnetism in the Age of Sail by A.R.T. Jonkers: “In 1904 a young American named Andrew Ellicott Douglass started to collect tree specimens. He was not seeking a pastime to fill his hours of leisure; his motivation was purely professional. Yet he was not employed by any forestry department or timber company, and he was neither a gardener not a botanist. For decades he continued to amass chunks of wood, all because of a lingering suspicion that a tree’s bark was shielding more than sap and cellulose. He was not interested in termites, or fungal parasites, or extracting new medicine from plants. Douglass was an astronomer, and he was searching for evidence of sunspots.”

The idea that an astronomer seeking to study the sun would proceed by making incisions into trees, as if looking for solar fossils there—an astral forensics of the forest—is mind-bogglingly beautiful and seems also to form the poetic subtext that makes Bradford Watson‘s short films so captivating.

[Image: From The Fountain, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Image: From The Fountain, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

A few years ago in Wired, meanwhile, veteran science journalist Steve Silberman wrote about the special effects created for Darren Aronofsky’s film The Fountain. Aronofsky, Silberman explained, stumbled across the photographic work of Peter Parks, “a marine biologist and photographer who lives in a 400-year-old cowshed west of London”:

Parks and his son run a home f/x shop based on a device they call the microzoom optical bench. Bristling with digital and film cameras, lenses, and Victorian prisms, their contraption can magnify a microliter of water up to 500,000 times or fill an Imax screen with the period at the end of this sentence. Into water they sprinkle yeast, dyes, solvents, and baby oil, along with other ingredients they decline to divulge. The secret of Parks’ technique is an odd law of fluid dynamics: The less fluid you have, the more it behaves like a solid. The upshot is that Parks can make a dash of curry powder cascading toward the lens look like an onslaught of flaming meteorites. “When these images are projected on a big screen, you feel like you’re looking at infinity,” he says. “That’s because the same forces at work in the water—gravitational effects, settlement, refractive indices—are happening in outer space.”

I mention this simply because it would be interesting to experiment with ultra-low-budget 2001-like astral effects using nothing but sequential shots of wood grain, with its stuttering bursts of spatial events constantly branching out from within.

[Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: Sliced truffles, randomly found via Google].

[Images: Sliced truffles, randomly found via Google].

[Image: From

[Image: From

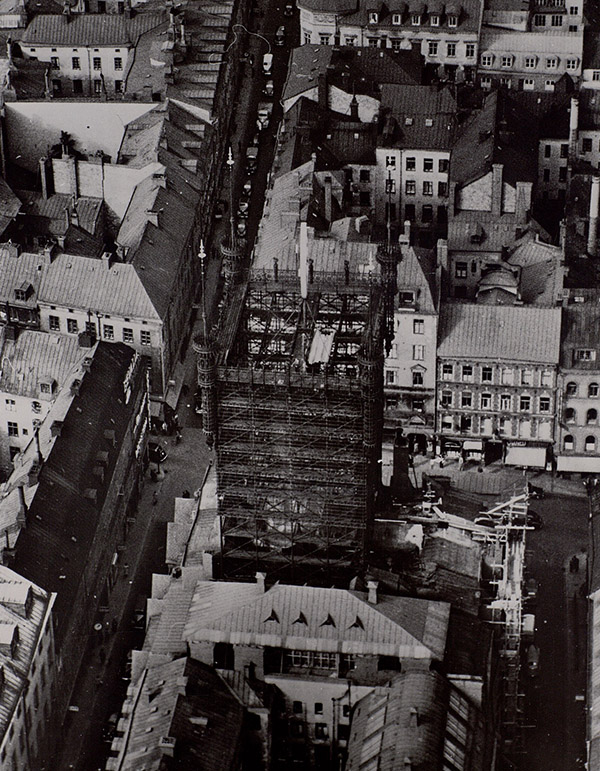

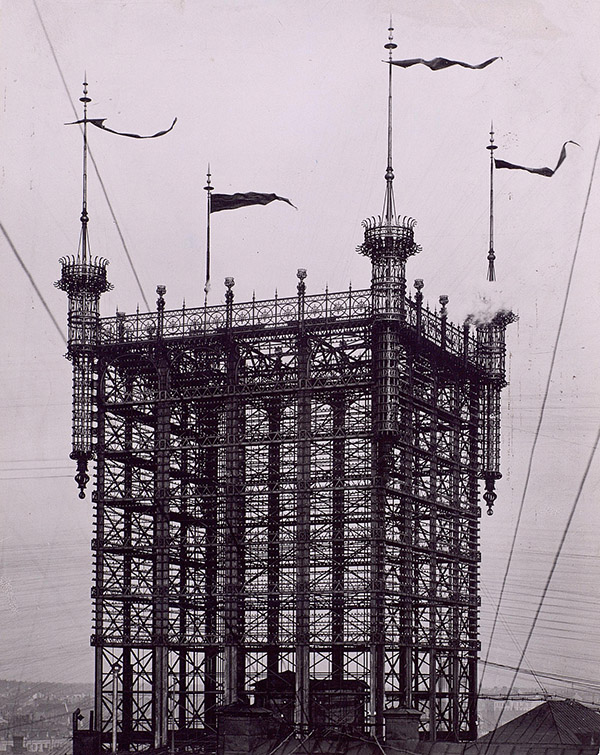

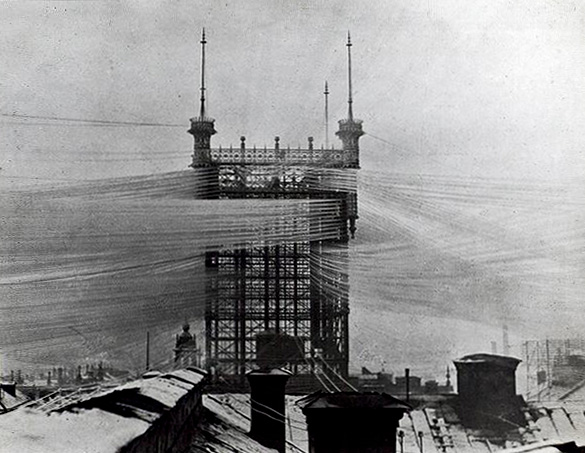

[Image: A telephone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, courtesy of the

[Image: A telephone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, courtesy of the  [Image: A telephone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, courtesy of the

[Image: A telephone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, courtesy of the  [Image: A telephone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, courtesy of the

[Image: A telephone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, courtesy of the

[Images: A telephone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, courtesy of the

[Images: A telephone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, courtesy of the  [Image: A telephone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, courtesy of the

[Image: A telephone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, courtesy of the  [Image: A telephone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, courtesy of the

[Image: A telephone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, courtesy of the  [Image: A telephone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, courtesy of the

[Image: A telephone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, courtesy of the

Abandoned terrapin turtles purchased 25 years ago at the height of popularity for

Abandoned terrapin turtles purchased 25 years ago at the height of popularity for

[Image: From “Derelict Electronics” by

[Image: From “Derelict Electronics” by  [Image: From “Derelict Electronics” by

[Image: From “Derelict Electronics” by

[Images: From “Derelict Electronics” by

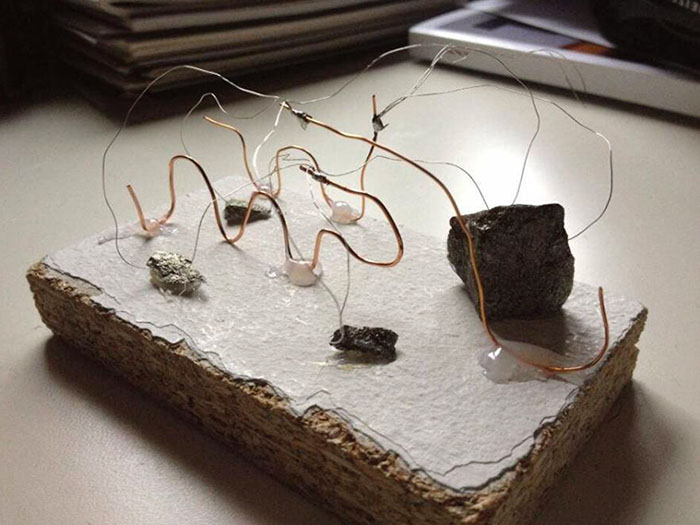

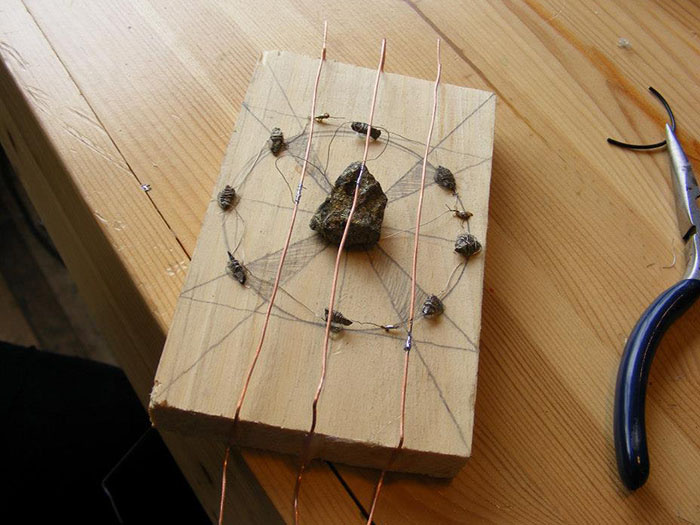

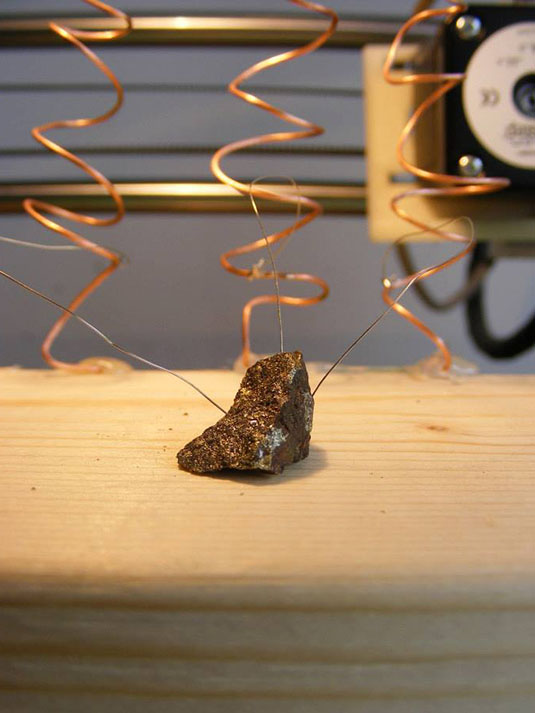

[Images: From “Derelict Electronics” by  [Image: Caleb Charland, “

[Image: Caleb Charland, “

[Images: Photos by

[Images: Photos by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Gates in Holywell, Peterborough; photo by Rowland Hobson, courtesy of

[Image: Gates in Holywell, Peterborough; photo by Rowland Hobson, courtesy of

[Image: Muscovites forced to masks against smoke from the burning forests and peat bogs of a drought-stricken Russia; photo by Alexander Demianchuk/Reuters].

[Image: Muscovites forced to masks against smoke from the burning forests and peat bogs of a drought-stricken Russia; photo by Alexander Demianchuk/Reuters]. [Image: The

[Image: The

[Image: A “ghost” tank; image via

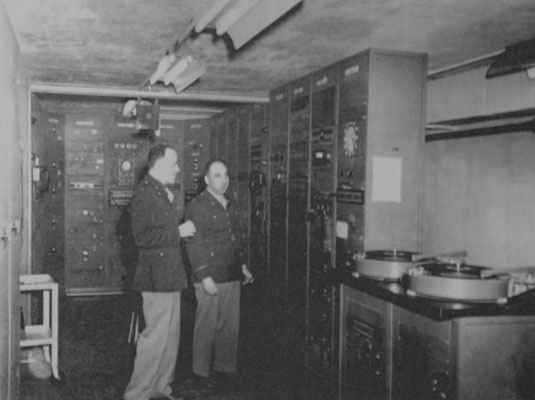

[Image: A “ghost” tank; image via  [Image: Signal Corps officers look at militarized turntables in Paris; via the

[Image: Signal Corps officers look at militarized turntables in Paris; via the

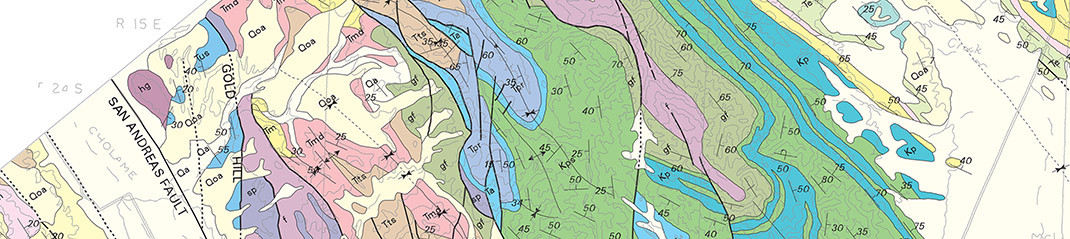

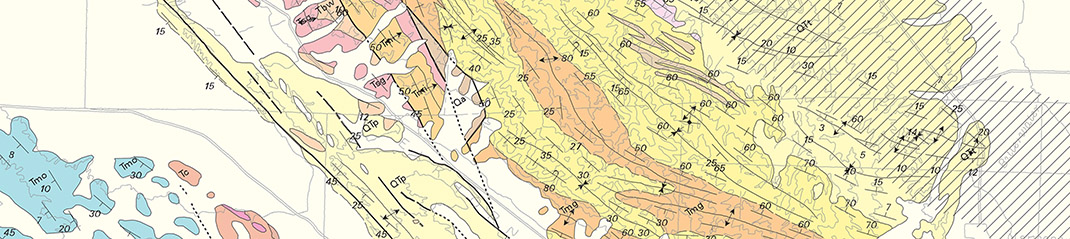

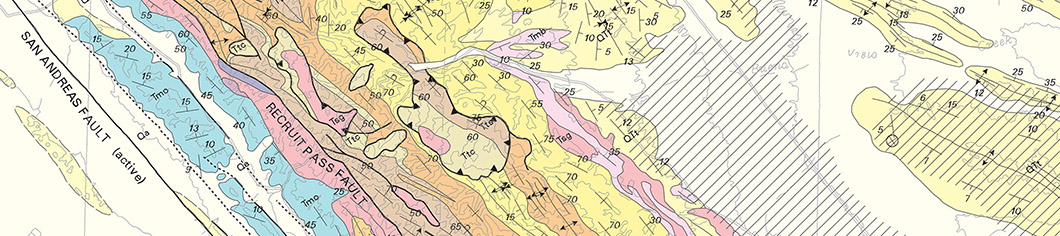

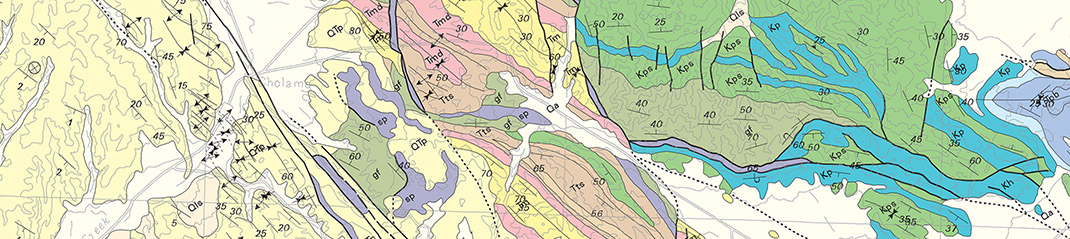

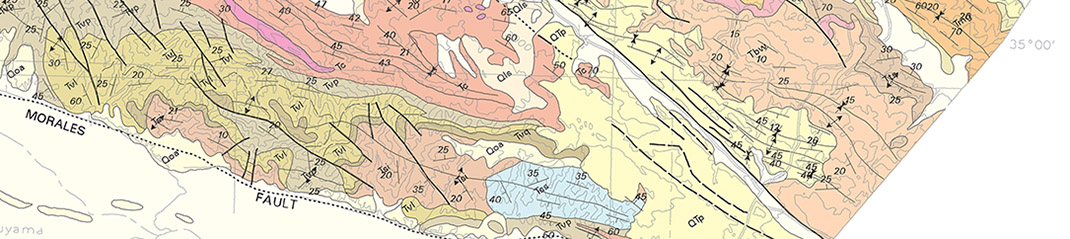

[Image: From a map of the San Andreas Fault, cutting through the

[Image: From a map of the San Andreas Fault, cutting through the

[Images: From a map of the San Andreas Fault, cutting through the

[Images: From a map of the San Andreas Fault, cutting through the

[Images: An

[Images: An

[Images: From a map of the San Andreas Fault, cutting through the

[Images: From a map of the San Andreas Fault, cutting through the