Michael Light, Gated “Monaco” Lake Las Vegas Homesites Looking West on Grand Corniche Drive, Bankrupt MonteLago Village and Ponte Vecchio Bridge Beyond, Henderson, Nevada (2010)

Michael Light, Gated “Monaco” Lake Las Vegas Homesites Looking West on Grand Corniche Drive, Bankrupt MonteLago Village and Ponte Vecchio Bridge Beyond, Henderson, Nevada (2010)

Photographer Michael Light divides his time between San Francisco and a remote house near Mono Lake, in the Sierra Nevada. An artist widely known for his aerial work, Light flies the trip himself in a small airplane, usually departing very early in the morning, near dawn, before the turbulence builds up.

Michael Light preps his airplane for flight; photo by Venue.

Michael Light preps his airplane for flight; photo by Venue.

Venue, BLDGBLOG’s collaborative project with Nicola Twilley of Edible Geography and the Nevada Museum of Art’s Center for Art + Environment, not only had the pleasure of flying with Light around Mono Lake, but of staying in his home for a few nights and learning more, over the course of many long conversations, about his work.

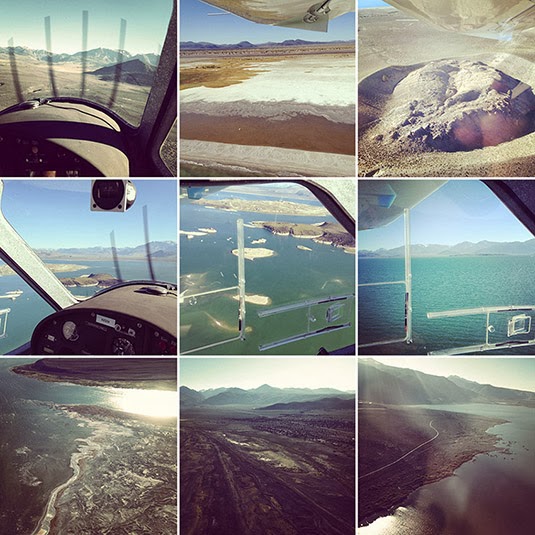

Flying with Michael Light over Mono Lake; photos by Venue.

Flying with Michael Light over Mono Lake; photos by Venue.

We took a nighttime hike and hunted for scorpions in the underbrush; we looked at aerial maps of the surrounding area—in fact, most of the U.S. Southwest—to discuss the invisible marbling of military & civilian airspace in the region; and we asked Light about his many projects, their different landscape emphases, the future of photography as a pursuit and profession, and what he might work on next.

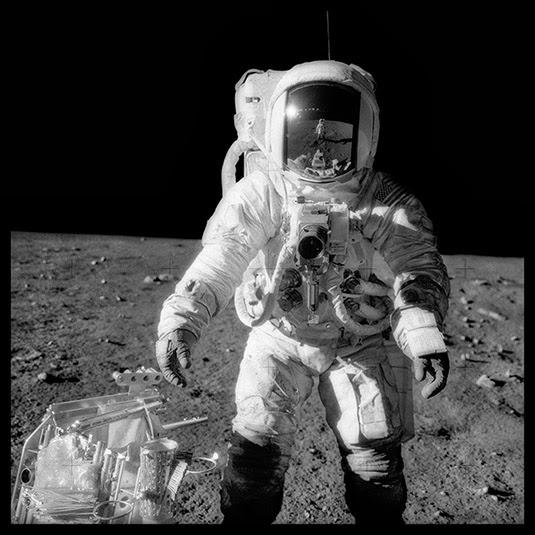

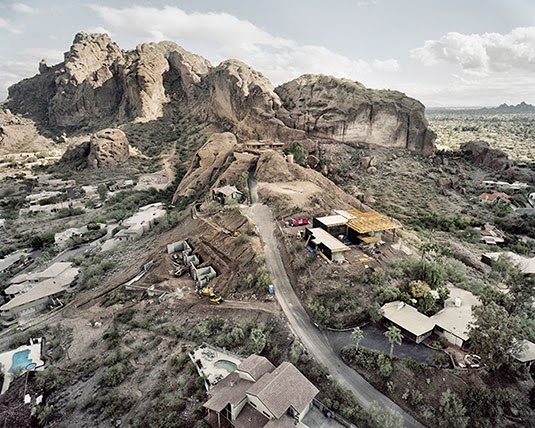

From SCUBA diving amidst the nuked ruins of WWII battleships in the most remote waters of the Pacific Ocean to spending years touching up and republishing photos of U.S. nuclear weapons tests for a spectacular and deeply unsettling book called 100 Suns, to his look at the Apollo program of the 1960s as an endeavor very much focused around the spatial experience of another landscape—the lunar surface—to his ongoing visual investigation of housing, urbanization, and rabid over-development in regions like Phoenix and Las Vegas, Light was never less than compelling.

With several great phrases—that “the mine is a city reversed,” or that the sunken ruins of WWII battleships “are dissolving like Alka-Seltzer” in the depths of the Pacific—and with an always caustic sense of humor, Light patiently answered our questions about his work both above the ground and below sea level, discussing what nuclear weapons have done the Western notion of the landscape sublime, what cameraphones have done to the professional photographer, and what it means to transgress today into the corporate-controlled air spaces of vast mining and extraction sites out west.

Michael Light, Shadow at 300’, 1300 hours, Deep Springs Valley, CA (2001)

Michael Light, Shadow at 300’, 1300 hours, Deep Springs Valley, CA (2001)

Michael Light, Clouds Over the Jonah Natural Gas Field, Pinedale, WY (2007)

Michael Light, Clouds Over the Jonah Natural Gas Field, Pinedale, WY (2007)

Michael Light: The short answer is that the aerial view affords a breadth of scale that offers direct access to many of the bigger, more “meta” themes that have always been of interest to me.

But let me take a few steps back and try to explain where all this came from. I got a B.A. in American Studies from Amherst many years ago, and I have since been an Americanist—not in the sense of being an apologist for America, but in the sense of someone trying to figure out what makes this country tick. It is a very, very vast country.

Michael Light, Sheep Hole Mountains at 400’, 0700 hours, Twentynine Palms, CA (2000)

Michael Light, Sheep Hole Mountains at 400’, 0700 hours, Twentynine Palms, CA (2000)

I grew up on the end of Long Island, and I was always getting onto Highway 80 or onto more southerly interstates and heading west. The metaphor that always accompanied me, oddly enough, was one of falling into America rather than crossing it. I was falling into the vastness of America and the sheer scale of it.

Of course, after I moved to California in 1986, I caught myself coming back east quite a bit, for family or for work, and those commercial air flights across the nation, flying coast to coast, were formative and endlessly interesting to me. I don’t ever lower the window shade as requested. If the weather is clear, the odds are that what’s unfolding below, geologically, is the main attraction for me. I just found myself looking down—or looking into—America a lot, and that sense of falling into the country just grew and evolved.

I did a big piece back in the 1990s, when I was still in graduate school. It took a couple of years, but I figured out how to make pretty decent images from 30,000 feet, from the seat of a commercial airliner. For instance, you have to sit in front of the engine so that the heat doesn’t blow the picture; and it’s a contrast game, trying to get enough clarity through all the atmospheric haze and through two layers of plexiglass, and so on and so forth. That piece was based specifically on commercial flights and it was liberating for me in lots of ways.

While working on one of those images, in particular, I had something of an epiphany—I think it was somewhere over Arizona. It’s very spare, arid country, and the incursions of human settlement into it that you see from above look very much like a colony on Mars might look, or the proverbial lunar colony, and I thought “Ah ha! Look at that!” And I realized, at that moment, that maybe I could try to find or document something like a planetary landscape: the way humans live at a planetary scale and through planetary settlements.

Michael Light, Chidago Canyon at 500’, 1800 hours, Chalfant, CA (2001)

Michael Light, Chidago Canyon at 500’, 1800 hours, Chalfant, CA (2001)

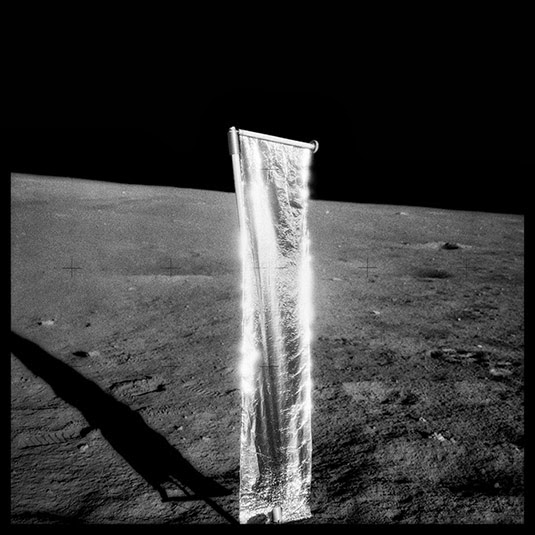

This was what got me, pretty soon thereafter, thinking above and beyond the earth: looking toward NASA, and their various programs over the past few decades, and that eventually became Full Moon.

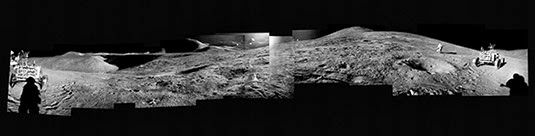

FULL MOON: Composite of David Scott Seen Twice on Hadley Delta Mountain; Photographed by James Irwin, Apollo 15, 1971 (1999)

FULL MOON: Composite of David Scott Seen Twice on Hadley Delta Mountain; Photographed by James Irwin, Apollo 15, 1971 (1999)

Manaugh: There’s an interesting book called Moondust by Andrew Smith, which began with Smith’s realization that we are soon approaching an historical moment when every human being who has walked on the moon will be dead. He set about trying to interview every living person—every American astronaut—who has set foot there. What makes it especially fascinating is that Smith portrays the entire Apollo program as a kind of vast landscape project, or act of landscape exploration, as if the whole thing had really just been at attempt at staging a real-life Caspar David Friedrich painting with seemingly endless Cold War funds to back it up. The place of Full Moon in your own work seems to echo that idea, of NASA lunar photography as something like the apotheosis of American natural landscape photography.

Light: The Apollo program was absolutely a landscape project—but also an extreme aerial project. And Full Moon, of course, was also driven by my own interest in the aerial view, or the aerial exterior. That project is nothing if not a really serious exploration of the aerial: that is, if you keep going up and up, the world becomes quite circular and alien. You see the world quite literally as a planet.

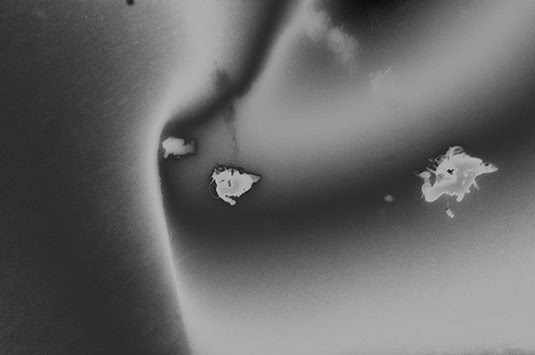

FULL MOON: The Ocean of Storms and the Known Sea; Photographed by Kenneth Mattingly, Apollo 16, April 16-27, 1972 (1999)

FULL MOON: The Ocean of Storms and the Known Sea; Photographed by Kenneth Mattingly, Apollo 16, April 16-27, 1972 (1999)

Anyway, for me, yes, the aerial view has an intense physicality. I’ve been flying planes since before I was driving. I soloed in gliders—engineless aircraft—by 14, and, by 16, I had a private pilot’s license. A glider offers a particularly intimate and very physical way of flying, because you have to work with thermals and updrafts. You don’t have an engine. You actually want it to be turbulent and bumpy up there, because that means that the air is unstable—that parts of the atmosphere are going up and other parts are going down—and, if you can stay in those up parts and find the updrafts, then you can ride it out for hours.

Also, I was lucky enough to start SCUBA diving at the age of 9.

Michael Light at 9 years old, Bimini, Bahamas (1972)

Michael Light at 9 years old, Bimini, Bahamas (1972)

Flying and going underwater are completely connected, at least in my mind. The three-dimensionality of each of them is something I’ve experienced from a very early age, and it is one of my greatest ongoing pleasures. I would say that there’s a tremendous amount of physical pleasure in both—and that, occasionally, it would even be accurate to call it ecstasy.

It’s like skiing or long-distance running: everything’s in the groove, everything sort of falls into place, you’re flying really beautifully, or, oftentimes in my work, you’re transgressing over something, or you’ve got a very intense subject, and you are trying to figure something out as an artist or as a citizen.

Michael Light at 49 years old, Petaluma, CA (2012)

Michael Light at 49 years old, Petaluma, CA (2012)

You mentioned delirium. There’s also a certain kind of delirium—a spatial delirium, sure—simply in the pleasure of learning something new and, for me, hopefully putting that 3-dimensional experience into 2-dimensional photographic form. And if it’s good—if the image is good—then hopefully other people can get some of what I got.

Manaugh: This reminds me of a conversation I had with a writer named Kitty Hauser about the history of aerial archaeology. To make a long story short, aerial archaeology, using photographs, was born from military reconnaissance flights over the European front in World War I. The pilots there began noticing that they could see features in the landscape—such as buried or ruined buildings—that were invisible from the ground. When that technique of viewing from above was later exported to England, particularly as the leisure classes and retired military types found the free time and the personal wealth to purchase private airplanes, aerial archaeology as a pursuit really took off, if you’ll excuse the pun. And these early pioneers began to realize that, for example, there are certain times of day when things are more clearly revealed by the angle of the sun, including shadows appearing in wheat and barley fields that, when seen from above, are revealed to be an archaeological site otherwise hidden beneath the plant life. I’m curious how coming back to the same locations at certain times of day, or in certain kinds of light, can make sites or landscapes into radically different photographic experiences—with different depths or different reliefs—and how you plan for that in your shots.

Light: If I go out on an expedition for weeks shooting with an assistant, I don’t immediately fall into that groove. A few days in, everything will align. It certainly is a kind of discipline. You’re flying and imaging and circling—again and again and again, around and around and around—because you can’t just move the camera two inches to the left, or wait 15 minutes. You’re moving along at 60 miles an hour through space. So you have to shoot it again and again and again, until, finally, you get to a point where your physical senses are moving faster than your mind, and you’ve made all the shots that you think you should make—which are generally the worst ones—and it’s at that point that you come up with something genuinely new.

Specifically, I tend to shoot early in the morning and then again in the evening, which is pretty much standard practice because, of course, the lower axial light gives that 3-dimensionality and creates a feeling of revelation. Every once in a while, though, I will shoot in the desert at midday, but it’s usually only when I’m specifically seeking a flat, blown out, almost stunning or hallucinatory light.

Michael Light, Deep Springs Valley at 500’, 1600 hours, Big Pine, CA (2001)

Michael Light, Deep Springs Valley at 500’, 1600 hours, Big Pine, CA (2001)

But, early in the morning, the sun seems to go off in the desert like a gun—and, of course, the sun is much softer in the evening, because there’s so much more dust in the air. You really have to get up early. I’ll shoot for an hour and a half, which is all I can really take with the doors off of the aircraft. It’s very windy. It’s very intense. The camera I use is about 20 pounds. So we’ll come back and we’ll have some breakfast—and I’m exhausted. I’ll probably nap around noon for an hour or two then, come 4:00pm or so, we gather our forces and go back up.

It’s always much more turbulent in the afternoon in summer. Summer is when I tend to fly, though, because, of course, in the colder months it’s just too cold. It’s also just a lot more dangerous to cross the mountains when there’s snow on them.

But, on summer afternoons, it can be a wild ride. You strap in there tight. My glider background is helpful here; I know the plane will continue to fly, for instance, and that there’s nothing to be super-scared of. I know I’m at the edges of my equipment’s performance. The specifications on the plane degrade measurably when you take the doors off, because you generate a tremendous amount of drag. In hot temperatures, the engine also tends to run hot and, the hotter the summer air is, the fewer molecules there are under the wings of the aircraft, the fewer molecules there are to combust with the engine fuel, the fewer molecules there are for the propeller to bite into, and you get much more turbulent air. Your aircraft performance falls off measurably.

Michael Light, Afternoon Thunderstorm Looking West, Near Rock Springs, WY (2007)

Michael Light, Afternoon Thunderstorm Looking West, Near Rock Springs, WY (2007)

For example, I often fly from San Francisco over the Sierras to Mono Lake in the summer. The Sierras, on the west side, have a very gradual slope. But on the east side it’s a very dramatic, very steep escarpment. It’s a drop of 7,000 feet almost in a straight line. You have a very smooth, very fast trip up the western slope, but, when you get to the escarpment, you hit what’s called a “rotor.” That’s a very turbulent place where the usual land-to-airflow relationship completely falls apart, because the support has been taken away. For those five miles or so, going east, you’re in a tumbly, sometimes chaotic atmosphere and it can be extremely dangerous, depending on the speed of the wind.

When I hit the rotor, I just think of it in terms of river rafting: looking for eddies, back-flow currents, whirlpools, and so forth. Even though it’s invisible, I know where I’m going to hit turbulence. Even though I can’t see the air, I know, extrapolating from the way that water behaves, where the turbulence will be—like, beyond that rock mountain spire over there, it’s going to be gnarly.

Michael Light, City-Owned Motocross Park Looking North, I-70 Beyond, Lakewood, CO (2009)

Michael Light, City-Owned Motocross Park Looking North, I-70 Beyond, Lakewood, CO (2009)

To go back to your question: in the six, almost seven years I’ve been flying with engines, the landscape is so perceptually dependent on the type of light that’s illuminating it. You really do get radically different spaces in different kinds of light. A different kind of vibe. Seasons will also change the way a landscape looks—or, I should say, the light itself seasonally changes.

On an artistic level, the ever-changing nature of what I do and how I do it, and even the instability of my position in the sky over the landscape—it’s all part of my process and it’s something I enjoy.

Manaugh: Let’s go back to SCUBA diving. When we talked four or five years ago in Nevada, you were heading off to the Bikini Atoll, to dive amidst the ruins of U.S. warships, and I’d love to learn more about that project. How did it come about, what were you seeking to document, and what were the results? I’m also fascinated by analogy of being in the empty volume of the sky versus being buried in the very full volume of the ocean and how that affects the sense of space in your photography.

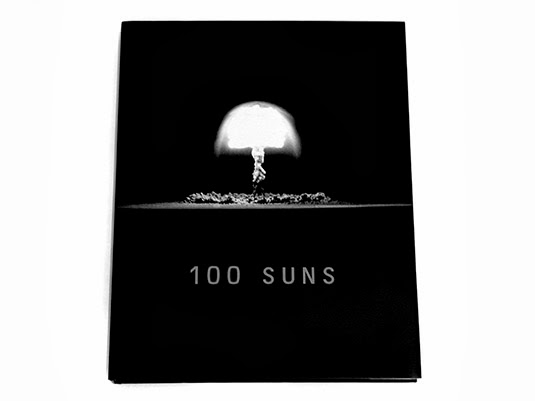

Light: The Bikini work grew out of my earlier involvement with imagery of nuclear detonations, which, as you know, was a project called 100 Suns. That was an archival endeavor that came out in 2003.

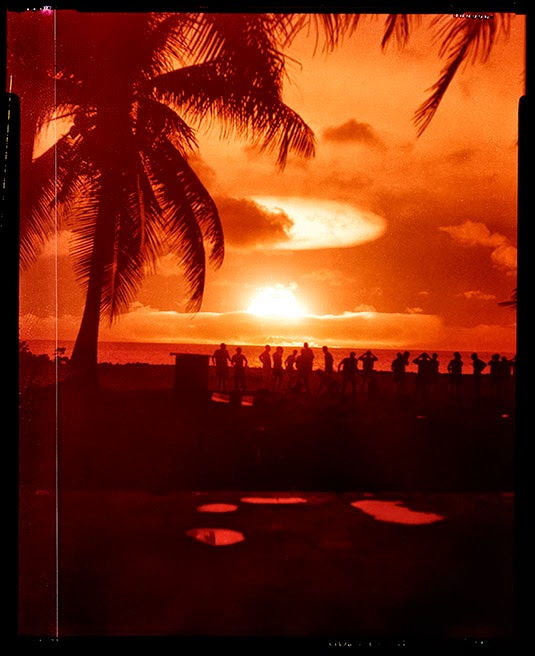

100 Suns (2003)

100 Suns (2003)

As a photographer or maker of images, I’m always as interested in trying to figure out the meaning of the trillions of photographs that have already been made as I am in making new ones of my own. And, culturally, I find it interesting to think about the meaning of photography, in the very large American contexts of Full Moon and 100 Suns. I think of both projects as landscape projects and, certainly, they are also investigations into American power and the peculiarities of American scale.

Nicola Twilley: As a side note, how does an archival project like 100 Suns work, technically, as far as reproducing the images goes?

Light: You scan them. You go in and you clean them up. You do whatever the approach of the hour is. You wind up almost lovingly inside each of the historical photographs. And you get very fond of them; you think of them almost as your own. Of course, they’re not—primarily because you haven’t had the experience of actually going to that space at that particular time and choosing how to make that image.

But I had a very strong desire to go—to make a pilgrimage—to, if not the Nevada Test Site, which I never could get into, then at least to the Pacific Proving Grounds, which I could get to. I tried to get into the Nevada Test Site. You can visit it, physically, but to get over it—in the air—and to make images is basically impossible. The last person to get permission to do that was Emmet Gowin, with his remarkable images. He got in in the 1990s. It took him a decade, and that was before 9/11. I tried again, and I was negotiating directly with the head of the site, but I just could never do it.

However, one can get out to Bikini, and the way one gets to Bikini hasn’t changed. At the time I went, there was a dive operation there run by the people of Bikini—who actually live 500 miles away, on a rather awful rock without a lagoon, in a place that they were moved to in 1945. They were basically booted off their atoll by the U.S. government. The people run this dive operation really for propaganda reasons, using it as a method to tell their story.

Michael Light, Bikini Island, Radioactively Uninhabitable Since 1954, Bikini Atoll (2003)

Michael Light, Bikini Island, Radioactively Uninhabitable Since 1954, Bikini Atoll (2003)

What one goes to dive for there are ships that were sunk in the Operation Crossroads tests of 1946.

At that point, the U.S. Navy—this was, of course, right after Hiroshima and Nagasaki—wanted to know if naval warfare was now utterly obsolete. Could a single bomb destroy an entire navy or a flotilla of ships?

100 SUNS: 058 BAKER/21 kilotons/Bikini Atoll/1946 (2003)

100 SUNS: 058 BAKER/21 kilotons/Bikini Atoll/1946 (2003)

So they gathered almost 100 vessels for the tests, making all sorts of strange, mythic gestures. For instance, they brought the Nagato, which Admiral Yamamoto was on when he orchestrated the attack on Pearl Harbor. They brought that all the way from Tokyo. They brought out the Prinz Eugen from Germany, which was Germany’s most modern battleship. They brought the first American aircraft carrier, the U.S.S. Saratoga, out.

The ships they chose were these giant wartime icons, and they were bombed both from the air, with the Able test, and from 90 feet underwater, by the Baker test. The Baker test gave us the most spectacularly iconic images of Bikini: a water column being blasted up into the sky with the Wilson bell cloud around it that we all know so well.

100 SUNS: 059 BAKER/21 kilotons/Bikini Atoll/1946 (2003)

100 SUNS: 059 BAKER/21 kilotons/Bikini Atoll/1946 (2003)

Those ships are 180 feet down at the bottom of Bikini Lagoon, to this day. They were functional at the time, and they were fully loaded with weaponry and fuel. They were unpopulated, although there were farm animals chained to the decks of the ships. So it’s creepy.

Diving there is pretty hairy. It’s way beyond recreational safety diving limits. 180 feet is dark. 180 feet is cold. You take on a tremendous amount of nitrogen down there. It’s pretty technical. You have to do decompression diving, which is inherently dangerous—you have to breathe helium trimix at about thirty feet below the boat for nearly an hour after twenty minutes at depth, hoping that no tiger shark comes along to eat you, as you adjust.

Michael Light, Shark, Bikini Lagoon (2007)

Michael Light, Shark, Bikini Lagoon (2007)

Once you’re down there, you can penetrate the ships, which are dissolving like Alka-Seltzer. It’s very entropic. You’re suffering, at that depth, from nitrogen narcosis. It’s like having three martinis. You’re pretty zonked out.

I went twice: in 2003 and, again, in 2007. During those trips, I made images from the air, on the surface, and underwater. I dove Bikini Lagoon, down to those ships on the bottom, twice.

Michael Light, Diver descending to 180 feet, Bikini Lagoon (2007)

Michael Light, Diver descending to 180 feet, Bikini Lagoon (2007)

It was one of the most challenging landscapes I have ever worked in, because almost inconceivable violence occurred to these places—both to Bikini Atoll and to Enewetak Atoll. I only physically went to Bikini Atoll, although I did fly over Enewetak. But both atolls were subjected to human gestures that are, as I said, almost inconceivably violent. To try to represent that photographically is very, very difficult.

In fact, the radiological disaster that occurred in 1954 happened simply because the winds changed direction at the wrong time, blowing back over the atoll at Bikini. During the largest nuclear detonation the United States ever did out there, which was 15 megatons, the winds shifted and everything blew back over the islands. It’s the worst radiological disaster in U.S. history.

Manaugh: I don’t want to sound naïve, but is it safe even to be there? Can you walk around and swim in the water and not get radiation poisoning?

Light: Bikini Atoll is still radioactive and still uninhabited to this day, but, yes, you can go there. As long as you don’t drink the water or eat the coconuts—anything that actually comes in contact with the soil, which has a layer of Cesium-137 in it—then you’re fine. The islands have healed. You know, it’s tropical. They’ve healed. There aren’t five-headed crabs walking around. The fish are fine; you can eat the fish. But it’s still pretty radioactive. I’m walking around in a Speedo bathing suit, thinking, “Wow, I’m glad I’m never having kids, ever!” You can’t feel radiation, but it’s there.

So there you are, having a tropical paradise moment, surrounded by tropical paradise visuals, yet you know, in your head, that this is one of the most violent landscapes on earth.

100 SUNS: 086 MOHAWK/360 kilotons/Enewetak Atoll/1956 (2003)

100 SUNS: 086 MOHAWK/360 kilotons/Enewetak Atoll/1956 (2003)

Two commercial aircraft fly the Marshall Islands. There is no access to private aircraft. The distances are too great. Bikini and Enewetak are in the middle of nowhere—that’s why they were used as test sites in the first place. To get aerial access to them was extremely difficult. I had to shoot from those two commercial air shuttles.

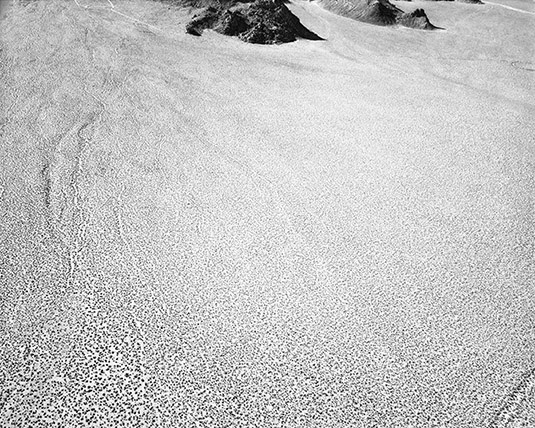

Over Enewetak I was able to get some pretty great images of the Mike crater. Mike was the first H-bomb test or, I should say, the first test of a “thermonuclear device.” It was not a bomb.

Michael Light, Mile-Wide, 200’ Deep 1952 MIKE Crater, 10.4 Megatons, Enewetak Atoll (2003)

Michael Light, Mile-Wide, 200’ Deep 1952 MIKE Crater, 10.4 Megatons, Enewetak Atoll (2003)

That was Edward Teller’s baby, and one big-ass crater. That was 10.4 megatons. The scale of that kind of explosion dwarfs all of the ordinance detonated in both world wars combined. Five seconds after that detonation, the fireball alone was five miles wide. These were really, really big explosions. It’s hard to get your head around how big they were.

100 SUNS: 065 MIKE/10.4 megatons/Enewetak Atoll/1952 (2003)

100 SUNS: 065 MIKE/10.4 megatons/Enewetak Atoll/1952 (2003)

Getting above and working with the Mike crater was terrific. I was able to get above Bikini, but not above the Bravo crater or out to the farthest edge of the atoll. Bravo was the 15-megaton test that left Bikini radioactive.

100 SUNS: 099 BRAVO/15 megatons/Bikini Atoll/1954 (2003)

100 SUNS: 099 BRAVO/15 megatons/Bikini Atoll/1954 (2003)

However, I was able to dive in the Bravo crater while I was there, which was one of the creepiest experiences of my life. It’s still quite radioactive out on the edge of the crater. There’s a bunker right on the edge of Bravo Crater that’s sheared off at the top.

Michael Light, Radioactive Bunker Facing Mile-Wide, 200’ Deep 1954 BRAVO Crater, Bikini Atoll (2003)

Michael Light, Radioactive Bunker Facing Mile-Wide, 200’ Deep 1954 BRAVO Crater, Bikini Atoll (2003)

Anyway, it’s obviously very deep and very rich territory. It was pretty amazing to be able to make the pilgrimage after having spent so much time with the archival material as I worked on 100 Suns. I have always felt ambivalent about the Bikini work. I’ve never known quite what to do with it. It is hard to work out there. I think that, ultimately, I will do a small book that will move between historical imagery of the ships and of the servicemen. There were 40,000 servicemen stationed there for several years while the Crossroads tests were happening.

I went back in 2007—I think that was right after you and I first talked about this. I got to do some aerial work and some more work on the ground, but, primarily, that trip was about bringing out a digital camera, which I did not have in 2003, and using it underwater. I had a housing and some lights, but I was not very successful in imaging those ships recognizably at those depths. It’s hard.

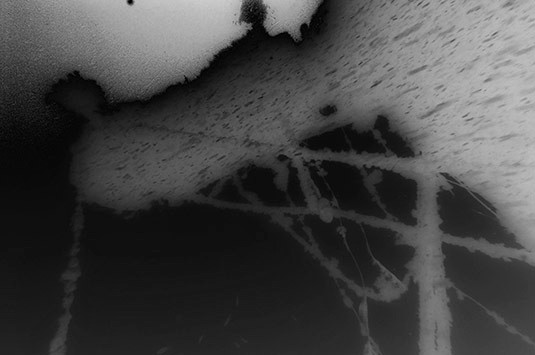

Michael Light, Ship Sunk by 1946 Crossroads Tests, Bikini Lagoon (2007)

Michael Light, Ship Sunk by 1946 Crossroads Tests, Bikini Lagoon (2007)

There’s a lot of organic matter in the water. It’s incredibly dark. It’s very difficult to figure out, conceptually, a way to image the country’s first aircraft carrier. For example, I can’t back away from it enough, underwater, to get the whole thing. In theory, one could put together composite images, shot at a fairly close level, and then sort of stitch together what should look like a ship. But it’s a challenge.

Michael Light, Growth on Ship Sunk By 1946 Crossroads Tests, Bikini Lagoon (2007)

Michael Light, Growth on Ship Sunk By 1946 Crossroads Tests, Bikini Lagoon (2007)

For me, throughout the Bikini work, both in 2003 and in 2007, I have taken the approach of reversing the positive as a conceit toward a sense of visually representing radiation and visually suggesting multiple energy sources other than the sun—multiple sources of light. There are also questions about narrative: about entropy, light, Hades, narcosis, dissolution.

You’ve got this kind of X-ray death trip, if you will.

Michael Light, Tower of the IJN Nagato Battleship, Sunk By 1946 Crossroads Tests, Bikini Lagoon (2007)

Michael Light, Tower of the IJN Nagato Battleship, Sunk By 1946 Crossroads Tests, Bikini Lagoon (2007)

It’s a very, very strong feeling, diving amongst those ships, and the ghosts of all the people who died on those ships, and knowing what they were used for and how they were sunk. It almost feels like the last gasp of an industrial era that’s now long over and gone. It was really an age of iron. It’s as far from the digital world that we live in now that you can imagine. It’s a dead era, and the work is tough. It’s not warm and fuzzy, or nostalgic. None of that is what Bikini is about. It’s about as dark as you can get.

Michael Light, Along the USS Saratoga, Sunk By 1946 Crossroads Tests, Bikini Lagoon (2007)

Michael Light, Along the USS Saratoga, Sunk By 1946 Crossroads Tests, Bikini Lagoon (2007)

Manaugh: In the context of 100 Suns and even hearing you say things like, “as dark as you can get,” it almost seems as though sites like the Mike crater and even these tropical ruins are like spatial byproducts of very large-scale light events. It’s as if the light of a counter-sun—the nuclear explosion—has created its own landscapes of extreme over-exposure and violence. The scenes you’re documenting, in a sense, are byproducts of light.

Light: Yes, some of this is important to me, and I do tend to think oppositionally, in rather binary terms.

Michael Light, Inside Radioactive Photographic Bunker Built In 1956, Aomon Island, Bikini Atoll (2003)

Michael Light, Inside Radioactive Photographic Bunker Built In 1956, Aomon Island, Bikini Atoll (2003)

There are so many levels of meaning to the bomb. There are landscape meanings. There are political meanings. There are industrial meanings. There are scientific meanings. To me, as I mentioned, this is a landscape book at bottom.

I personally see the moment that the Mike device detonated in 1952 as the moment when the classical landscape sublime—which, of course, up to that point was the domain of either the divine or of massively powerful natural forces beyond human control—switched. In 1952, the landscape sublime shifted wholly over to humans as the architect.

I was interested in looking closer at that moment when humans became “the divine”—as powerful as, if not more powerful than, the natural forces that they’re subject to on the planet. What was the effect of that—what did that do to landscape representation—when the sublime became an architecture of ourselves?

100 SUNS: 081 TRUCKEE/210 kilotons/Christmas Island/1962 (2003)

100 SUNS: 081 TRUCKEE/210 kilotons/Christmas Island/1962 (2003)

With the attainment of a thermonuclear fusion device, humans are igniting their own stars. What does that mean in landscape terms? What does that mean in architectural terms? When you talk about light itself creating a landscape and leaving behind these giant craters, it’s very resonant territory.

Arguably, humans firing up their own stars could be seen as the absolute pinnacle of a tool-bearing civilization—although it’s equally fair to say that it could be seen as humanity’s greatest tragedy, because it came out of a cauldron of violence and was immediately put back into a cauldron of violence.

100 SUNS: 093 BRAVO/15 megatons/Bikini Atoll/1954 (2003)

100 SUNS: 093 BRAVO/15 megatons/Bikini Atoll/1954 (2003)

To bring us back to ground a little bit here, I did 100 Suns, and I did Full Moon, and I continue to do my aerial forays into the American West, because these are things that I want to learn about and try to understand. I just truly didn’t understand fusion and fission; I really didn’t understand space. I think that, while I have a taste—and the human mind has a taste—for scale, there’s only so much scale that we can take. Even then, we need to have it served to us in smaller chunks.

I found that other books and investigations pertaining to outer space were just way too broad and, in the end, didn’t tell me anything. I don’t get much out of the Hubble images, for example. They’re too big. I have no entranceway into those to conceptualize or think about the subject, so I wind up with cotton candy or some nebula image that’s pretty, sure, but I can’t get any substance out of it.

100 Suns never would have happened without having spent five years on the surface of the moon, metaphorically. Studying the nature of light in a vacuum—that was really the primary interest of mine, artistically, in taking on that project.

FULL MOON: Astronaut’s Shadow; Photographed by Harrison Schmitt, Apollo 17, 1972 (1999)

FULL MOON: Astronaut’s Shadow; Photographed by Harrison Schmitt, Apollo 17, 1972 (1999)

How does light work without atmosphere to break it up? It’s sharper than anything our eyes have evolved to see, and it behaves very differently than it does when diffused by an atmosphere. What does that do to the physical act—the actual technology—of photography as it tries to capture that light? What does that light do to a landscape?

What does that landscape do to all the other landscapes we’ve already seen in the history of landscape photography?

FULL MOON: Morning Sun Near Surveyor Crater, With Blue Lens Flare; Photographed by Charles Conrad, Apollo 12, 1969 (1999)

FULL MOON: Morning Sun Near Surveyor Crater, With Blue Lens Flare; Photographed by Charles Conrad, Apollo 12, 1969 (1999)

I spent a lot of time looking at the sun’s effects on the surface of the moon, in near-vacuum conditions, and I thought, “Well, what’s the next logical step for this?”

FULL MOON: Solar Wind Collector; Photographed by Alan Bean, Apollo 12, 1969 (1999)

FULL MOON: Solar Wind Collector; Photographed by Alan Bean, Apollo 12, 1969 (1999)

Certainly, it’s not Mars, as so many publishers would suggest. It seemed more logical to go look directly into that sun and, at least in terms of the 20th century, very clear that I should step back just two or three decades, and deal with the bomb. Of course, the Apollo program never would have happened without ICBMs.

On that level, it’s logical—but it also acts as a kind of psychological journey. In 100 Suns, there’s no handholding that occurs for the viewer to guide them between attraction and repulsion. You’re just thrown into it. There’s science afterward; there’s text afterward; there are explanations afterward; there are politics afterward. But that kind of frontal experience was what I wanted you to feel, as a viewer.

It was a very daunting subject. The scale of America, and the scale of its power, offers an infinite mountain of mystery.

Twilley: In terms of both the moon and some of these military ruins, like the Nevada Test Site, physical access for the photographer is all but impossible. Has this made you interested in remote-viewing, remotely controlled cameras, or even drone photography? What might those technologies do, not necessarily to the future of photography, but to the future of the photographer?

Light: Absolutely. I think it’s important to remember that the vast majority of the Apollo photographs were made without anyone looking through a viewfinder.

Those cameras were mounted on the surface of the moon or on the chest area of the spacesuit. With a proper wide-angle lens and an electric advance, the astronauts basically just pointed their bodies in 360-degree circles, at whatever area they were collecting the samples from, and that was the photograph. They were trained very carefully to make sure they could operate the cameras, and there are certainly examples of handheld camera images on the surface of the moon, but a lot of the images were these sort of automatic images you’re talking about—photography without a photographer.

FULL MOON: Alan Bean at Sharp Crater With the Handtool Carrier; Photographed by Charles Conrad, Apollo 12, 1969 (1999)

FULL MOON: Alan Bean at Sharp Crater With the Handtool Carrier; Photographed by Charles Conrad, Apollo 12, 1969 (1999)

It’s one of those things that I find interesting about Full Moon, that what we consider to be interesting, photographically, can happen absent of a human set of eyes making the image. Today, as you mention, it’s only getting more extreme.

I should say, at this particular photographic moment, as a photographer myself, I feel overwhelmed. I have not figured out where photography is going. I don’t think anyone has. I certainly know that it’s changing, radically, and sometimes in ways that make me want to run back to the 19th century.

For one thing, everyone’s a photographer now, because everyone has a phone, and those cameras are getting very good. The cameras themselves are doing more and more of the work, as well, work that, traditionally, was the field of the photographer, so the quality of photographs—in the classic sense of things like quality of exposure, density, resolution, contrast, and so forth—is going up and up and up. And, of course, as you well know, there are now systems in place for total and instantaneous publishing of one’s work via the Internet. I think we are entering a world of total documentation.

Obviously, all of this visual information is going to continue to proliferate. I don’t know how to navigate my way through that. I tell myself—because I have my own methods, my own cameras, and my own crazy aerial platform—that my pictures have a view that you are not going to get from a drone.

Personal drones are going to proliferate, and our eyes, soon enough, are going to be able to go anywhere and everywhere without our bodies. Humans have a tremendous interest—they always have had—in extending themselves where they physically cannot go. That’s just picking up more speed now—it’s going faster and faster—and the density of the data is thickening, becoming smog.

I think that photography, or what we currently consider photography, will become more about the concept or the idea driving the picture than the actual picture itself. Maybe that has always been the case. Metaphors are obviously applicable to everything, and you can find them in everything, if you want to. It’s not so much the picture—or, it’s not so much the information in the picture—it’s the spin on it. Information does not equal meaning. Meaning is bigger than information.

I used to fly model aircraft as a kid. It’s a powerful fantasy: mounting a camera on a little electric helicopter and running it around the corner, lifting off over the fence, the hedgerow, the border, and seeing what you can see. I actually do it physically now, in airplanes, and I’m very invested in the physical experience of that. It’s a big part of my aerial work: the politics of transgressing private property in a capitalist society.

I may not be able to get into that gated community on the outskirts of Las Vegas—which is what I’m photographing now, a place called Lake Las Vegas—but, legally, I can get above it and I can make the stories and the images I want to make.

Michael Light, “Monaco” Lake Las Vegas Homes on Gated Grand Corniche Drive, Henderson, NV (2010)

Michael Light, “Monaco” Lake Las Vegas Homes on Gated Grand Corniche Drive, Henderson, NV (2010)

That homeowners’ association, or that world created by developers, wants total control over its narrative, and, in general, they have it. They exclude anyone who wants to tell a different story. So far, with the exception of military air space and occasional prohibited air space around nuclear power plants and that sort of thing, I can still tell my own stories, and I do.

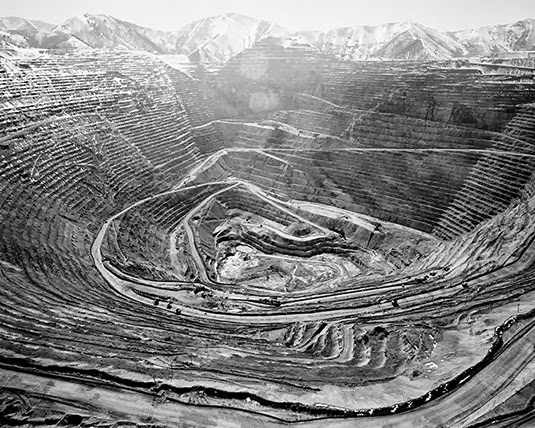

A couple of years ago I went out to Salt Lake City. I sold one of my big handmade books to the art museum there, and I also made an effort to see Kennecott Copper, which is owned by Rio Tinto. I thought they might be interested in buying some of the work—but, as it turned out, they were not at all interested, and, in fact, seemed to wish I didn’t exist.

I met with their PR person—a very nice, chatty PR kind of lady. I showed her this spectacular, 36-inch high and 44-inch wide book of photographs featuring this incredible, almost Wagnerian hole in the ground. And the only thing that she could say, upon seeing the book, was: “How on earth did you get permission?” Not: Wow, these are interesting pictures, or whatever. She instantly zoomed into the question of the legal permission to represent or tell the story of this site. I said: “Well, I didn’t get permission, actually, because I didn’t need permission.” And that was anathema to her; it was anathema to the whole corporate structure that wants to control the story of the Bingham Mine.

Michael Light, Earth’s Largest Excavation, 2.5 Miles Wide and .5 Miles Deep, Bingham Copper Mine, UT (2006)

Michael Light, Earth’s Largest Excavation, 2.5 Miles Wide and .5 Miles Deep, Bingham Copper Mine, UT (2006)

Anyway, I think it’s through my own selfishness that I would not want to send a drone up to transgress over a site when I could do it, instead. I could just sit at my computer screen and kick back in my chair—but we spend enough time in chairs as it is. It’s more that I am putting my butt on the line; I’m breaking no laws, but there is the experience of physical exploration that I would be denied by using drones. Obviously, in areas where I truly cannot go—like the moon—or where I wouldn’t want to go—like on the edge of one of those nuclear detonations—then I’d be thrilled to have a remote.

Manaugh: You mentioned control over the narrative of the copper mine. It’s as if Kennecott has two-dimensional control over their narrative, through image rights, but they don’t have volumetric, or three-dimensional, control over the narrative, which you can enter into with an airplane and then relate to others in a totally different way.

Light: Of course.

My particular approach, aerially, is very different. The obvious answer is: why not just Google Map it, and zoom in, and then throw a little three-dimensionality on it by moving a little Google Earth lever? But the actual act of going in at the low altitudes that I do lets me make these particular images. I don’t do verticals; I do obliques, because they allow for a relational tableau to happen. To go in low—to make that physical transgression over Bingham or over Lake Las Vegas or over this or that development—is great, and I think it’s a viewpoint that is unique.

Michael Light, Looking East Over Unbuilt “Ascaya” Lots, Black Mountain Beyond, Henderson, NV (2010)

Michael Light, Looking East Over Unbuilt “Ascaya” Lots, Black Mountain Beyond, Henderson, NV (2010)

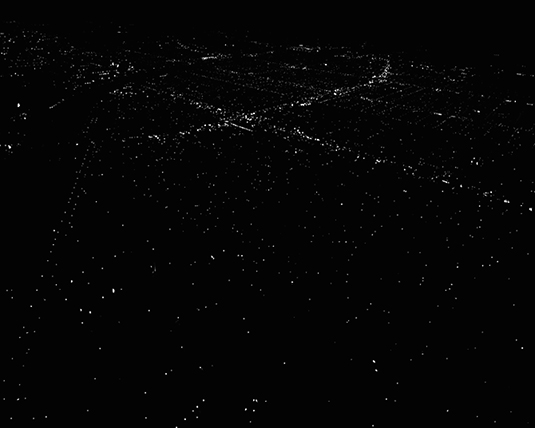

Manaugh: You’ve mentioned Las Vegas, but I’d also like to talk about your Los Angeles work. You basically have two oppositional series—L.A. Day and L.A. Night—which really makes explicit the role light plays in changing how we see a landscape. For instance, in L.A. Night, the city is represented as this William Blake-like microcosm of the universe, with the lights of the houses in the Hollywood hills, and the cars on the freeways, mimicking the stars above them. The city becomes a copy of the sky.

Michael Light, Untitled/Downtown Dusk, Los Angeles (2005)

Michael Light, Untitled/Downtown Dusk, Los Angeles (2005)

Then there’s L.A. Day, which confronts the massive Ballardian geometry of the freeways themselves, baking under the sun.

Michael Light, Long Beach Freeway and Atlantic Boulevard Looking Southeast, L.A. River Beyond (2004)

Michael Light, Long Beach Freeway and Atlantic Boulevard Looking Southeast, L.A. River Beyond (2004)

I’m interested in what the city is doing for you in these photographs. Is it a representation of the end of civilization, or is it a strange depiction of new, golden dawn for urban form? What is your attraction to and metaphoric use of the city—of Los Angeles, in particular?

Light: Well, these are very interesting questions. One thing to bear in mind, first of all, is that the day work and the night work is now quite old work to me. The day work was shot in 2004 and the night work was shot in 2005 and it’s just a Los Angeles; it’s not the Los Angeles. It’s very much a particular spot in time that I found myself at that moment. I’ll get into that in a little more detail in a minute.

Back in 1986, when I moved to San Francisco, I wanted to come west for a lot of reasons, one of which was to work for the environment. I had worked for the Sierra Club doing political lobbying with their D.C. office for a couple of years right out of school in the late 1980s. I’ve remained a pretty strong environmentalist, although I try not to make my work tendentious or overtly activist in that sense. I want to be more complicated than that.

Michael Light, Looking Northwest, Somewhere Near Torrance (2004)

Michael Light, Looking Northwest, Somewhere Near Torrance (2004)

Anyway, in San Francisco, the default attitude is to look down your nose at the Southland—like, “Oh, yeah, Los Angeles. It’s everything that’s wrong with America.” The more I’ve lived in California, though, which is 26 years now, the more I have come to realize that this is an extraordinarily common, but very facile, view of Los Angeles. I hope I have grown in the depth of my views about L.A., I’d say, because, if there’s any one thing I’ve learned about photographing Los Angeles—like anywhere else, but particularly L.A.—it’s that, every time you shoot, it’s a different city. L.A. in the spring is one thing. L.A. in the dry summer is another. L.A. day. L.A. night. L.A. color. L.A. black and white. I have been humbled, I think, in a positive way in my views of Los Angeles. Of course, maybe I’ve just gotten more cynical or maybe I’ve gotten a little more complicatedly environmental. But I’m not condemnatory about that city the way I used to be.

L.A. is a massive thing. This is one of the reasons why I was drawn to it in the first place. It’s so big. It’s so complex. Is it apocalyptic? Well, yes; it has a certain apocalyptic quality to it. But, if I’m trying to understand America, or trying to understand the bomb, how could I not try to understand L.A.?

So L.A. Day came directly out of doing 100 Suns. 100 Suns came out in 2003 and I had been spending a tremendous amount of time metaphorically looking at “suns.” Obviously, in L.A. Day, one of the major tropes is that I am shooting directly into the sun, and I’m dealing with air, light, and atmosphere. In that regard, I’m also exploring many of the same things as Full Moon.

I was also just beginning to work with 4×5 negatives, and wanted to go as high-key as possible, to go back into that annihilating desert light. A lot of it was shot either early in the morning or very late in the day, but the whiteness of the light at midday is a very dry, Western, annihilating light that I was also interested in investigating. There’s an image that I’m particularly fond of: it’s downtown L.A. with the river in front, and the city is almost vaporizing. It’s almost just lifting up into the ether. I guess I wasn’t overtly looking for a nuclear moment, something coming so literally from 100 Suns, but, in my mind, that image really—at least, metaphorically—bridges those two projects.

Michael Light, Downtown Los Angeles Looking West, 1st Street Bridge and L.A. River in Foreground (2004)

Michael Light, Downtown Los Angeles Looking West, 1st Street Bridge and L.A. River in Foreground (2004)

The night work was kind of a binary reflex. I had been thinking about the old 19th-century blue-sensitive films, where the skies would go pure white, for a while. Full Moon, obviously, is the reversal of that, where the ground—the surface of the moon—is white with undiluted sunlight and the sky is endlessly black.

In the day in L.A. you get the obverse: a terrestrial sky, if you will. L.A. Night is another reversal and a kind of the binary analogue to the moon and its vacuum sky.

Michael Light, Untitled/River Stars, Los Angeles (2005)

Michael Light, Untitled/River Stars, Los Angeles (2005)

Those things were operating in my mind, although the night work also came out of a technical challenge I wanted to face. I wanted to get this 4×5 camera to work from a helicopter. I can only go one-sixtieth of a second. Slower than that and I get a blur. The challenge was: can I actually get enough light on the film at one-sixtieth of a second, either at dusk or in pure dark? Can I even make this work?

I discovered very cheap—relatively speaking—Robinson R22 helicopters, operating out of Van Nuys, that I could get for something like $230 an hour with a pilot. The physical thrill of having your own private dragonfly, really, which is what these helicopters are, also drove my interest. I was doing all this day work and I thought, well: let’s try a night flight. Let’s actually drift over the vastness and the endlessness of the city, and all the light washing around in that basin. It is exquisitely sparkly. It’s delightful. It has some enchantment in a way that Los Angeles, in daylight, does not. It’s rife with metaphor with all the little lights standing in for all the little people.

Michael Light, Untitled/Hollywood, Los Angeles (2005)

Michael Light, Untitled/Hollywood, Los Angeles (2005)

I think that, in all of my work since the late 1980s, there has been a transposition between up and down, or a loss of gravitational pull, and that’s very important to me.

FULL MOON: Edward White at 17,500 mph Over the Gulf of Mexico; Photographed by James McDivitt, Gemini 4, 1965 (1999)

FULL MOON: Edward White at 17,500 mph Over the Gulf of Mexico; Photographed by James McDivitt, Gemini 4, 1965 (1999)

A sense of vertigo or spinning in space, the full 3-dimensionality of space—the spatial delirium we were talking about earlier. I’ve always been interested in imagery that gives me a sense of looking up when I am actually looking down. That reversal is something I try to look for.

Michael Light, Sawtooth Mountains Diptych, ID (2012)

Michael Light, Sawtooth Mountains Diptych, ID (2012)

But that night work was very much of a moment in time in my own production—meaning that I would not go back to L.A. and make pictures like that again.

The work I’m doing over Vegas couldn’t be more different. It’s color. It’s very much lower to the ground. It’s much more specific to its content. In aerial work for me, not only is there tremendous pleasure in moving through space, 3-dimensionally, there is also tremendous pleasure in moving over and around and amongst geology and amongst actual formations of the land. Much of the content of the western work is about that dialogue between geology and the built world.

Michael Light, Empty Lots in the “Marseilles” Lake Las Vegas Community, Henderson, NV (2011)

Michael Light, Empty Lots in the “Marseilles” Lake Las Vegas Community, Henderson, NV (2011)

The subtitle of my larger project, Some Dry Space, is An Inhabited West. My point is that there is no place that’s untouched anymore. The west is a giant human park.

But, that said, there is still lot of space left and it’s really fun to move through that space. It’s fun to say, well, okay, here’s Phoenix or here’s Los Angeles, but how can I make images that actually show the power of the geology of a place? How do I represent two different time scales? How do I photograph the human one and the tectonic one? I find that dialogue, between a human time frame and the time frame of the land, to be an interesting one. I try to capture both when I can, preferably adjacent to each other in the same picture.

Michael Light, New Construction On East Porter Drive, Camelback Mountain Beyond, Scottsdale, AZ (2007)

Michael Light, New Construction On East Porter Drive, Camelback Mountain Beyond, Scottsdale, AZ (2007)

Twilley: What have you been trying to capture or represent in your most recent trips out there?

Light: Every flight is different. Every mindset is different. I find that I take radically different pictures each time I go up. It’s an interesting thing. I’ve contained myself to two areas—Lake Las Vegas and the MacDonald Ranch, which is this whole side of a mountain that’s been completely sculpted into house pads. It is the most spectacular, simple engineering project I think I’ve ever seen. It’s very dramatic. Parts of it are built out; parts of it aren’t. I don’t know what the final awful sales name of the development will be, but these will be very high-end homes.

I’ve really taken on the domestic side of Las Vegas, where “California dreams” are to be had on the cheap—and then on the extraordinarily inflated side of things, the delusional, opulent side of things.

Vegas is a very easy target for the sophisticated East Coast cultural critic to come out and judge. But that line of critique is a dead end. It’s not new territory, and it also dismisses the people—the end-users—without asking any questions about how they got there. I’ll nail the developers any day of the week: this is a calculated, rationalized capitalist agenda for them. But the people at the end, on the receiving side of it, the people who are trying to build their lives and their dreams, on whatever unstable sands that they can or can’t afford out there—I would like to present them critically but without condemnation.

Michael Light, Halted “Bella Fiore” Houses and Bankrupt “Falls” Golf Course, Lake Las Vegas, Henderson, NV (2011)

Michael Light, Halted “Bella Fiore” Houses and Bankrupt “Falls” Golf Course, Lake Las Vegas, Henderson, NV (2011)

The L.A. work was too high and atmospheric to get political. Now that I’m down, flying much lower and getting closer and closer to the material, I think the work can carry more of an agenda. It is a presentation with sophisticated layering, I hope, rather than a blanket condemnation. Otherwise, I’m looking down my nose, saying, “Oh, look at these poor fools living in Las Vegas, while I’m up in San Francisco living the way people should live.”

The more work I do in Las Vegas, the more I see parallels between the mining industry—and the extraction history of the west—and the inhabitation industry. They do the same sort of things to the land; they grade, flatten, and format the land in similar ways. It can be hard to tell the difference sometimes between a large-scale housing development being prepped for construction and a new strip mine where some multinational firm is prospecting for metals.

Michael Light, Unbuilt “Ascaya” Lots and Cul De Sac Looking West, Henderson, NV (2011)

Michael Light, Unbuilt “Ascaya” Lots and Cul De Sac Looking West, Henderson, NV (2011)

In other words, the extraction industry and the inhabitation industry are two sides of the same coin. The terraforming that takes place to make a massive development on the outskirts of a city has the same order, and follows the same structure, as much of the terraforming done in the process of mining.

That was a revelation for me. The mine is a city reversed. It is its own architecture.

Michael Light, Hiking Trail and Unbuilt “Ascaya” Lots, Black Mountain Beyond, Henderson, NV (2010)

Michael Light, Hiking Trail and Unbuilt “Ascaya” Lots, Black Mountain Beyond, Henderson, NV (2010)

This latest shoot also resulted in some structural advances in the photographs, in the way that they are composed and the way that they are offset and fragmenting. I was pleased with it. I was also testing out a new camera I had rented.

Twilley: Are you shooting digital?

Light: I am beginning to. I’m trying. I’m renting all the Hasselblads—60 megapixels—that I can get my hands on.

Michael Light, Houses on the Edge of the Snake River Lava Plain, Jerome, ID (2009)

Michael Light, Houses on the Edge of the Snake River Lava Plain, Jerome, ID (2009)

Anyway, the more I photograph, the more I have become attracted to architecture and the meanings of architecture. As it appears here and there out west in the landscape, architecture stands out so much. It’s just plunked down, naked and exposed. Whatever intentions it has, if there are any, are so apparent.

As I have come to photograph these inhabited landmarks, it’s more and more obvious how the affluent choose to manifest their affluence through architecture. They manifest it by getting or obtaining a certain piece of land—a spectacular piece of land in the spectacular west—and then by building some sort of structure there. They want to insert themselves into the most sublime location possible.

They take in the sublime, as we all would, and as I do, but then they try to project it back out again through a generally dirty and dark architectural mirror. You see it on the Snake River, with the potato barons. You see it in Colorado. You see it in ski towns. In my view, it’s just a re-projection of the American business ego—let’s just call it the American ego—back out into the landscape, via this or that villa. It’s an architectural version of wanting now to be the true authors of the landscape sublime, and part of this abrupt shift from classical, uninhabited landscapes to built landscapes of our own monumental and violent design. That’s all part of what I mean by “the inhabited west.”

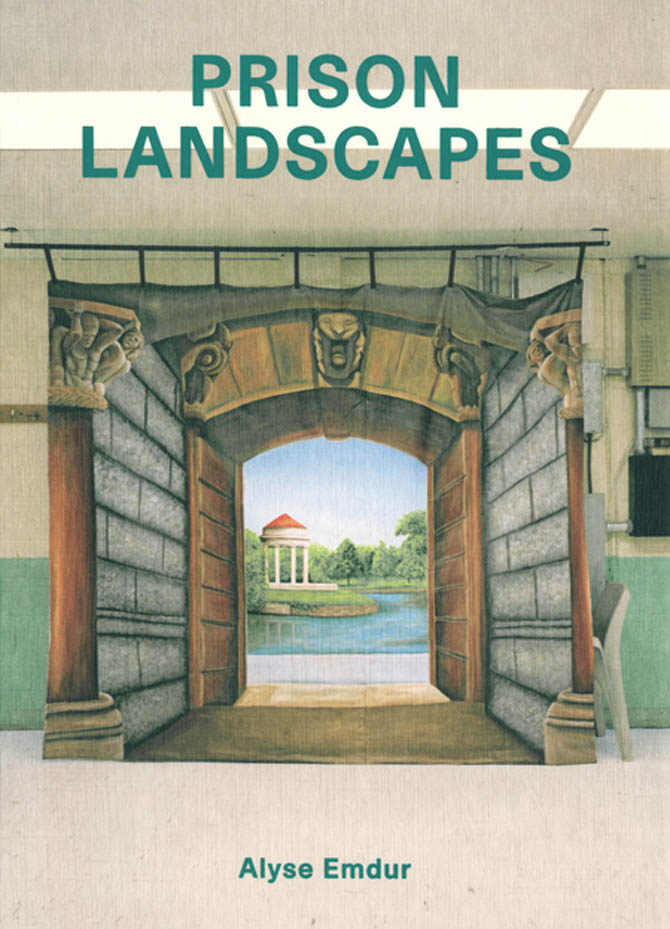

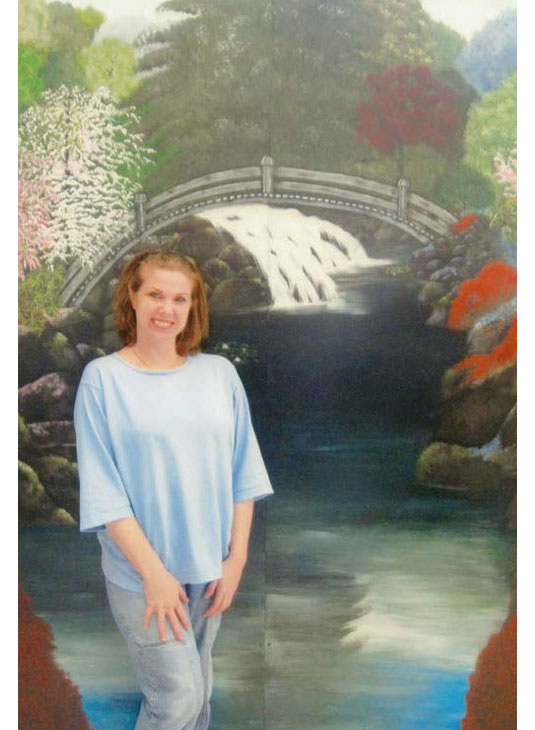

[Image: Prison Visiting Room Backdrop, Woodbourne Correctional Facility, New York; photograph by

[Image: Prison Visiting Room Backdrop, Woodbourne Correctional Facility, New York; photograph by  [Image:

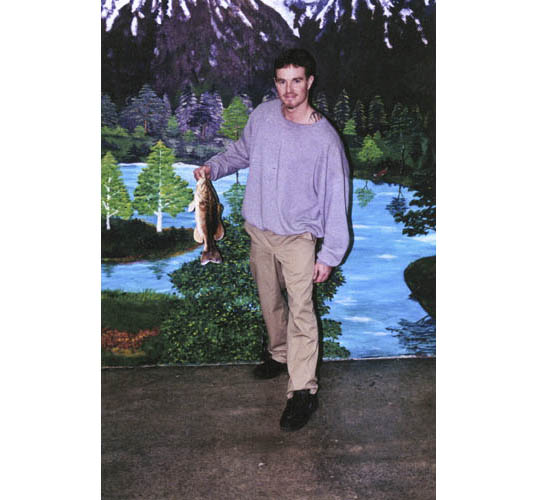

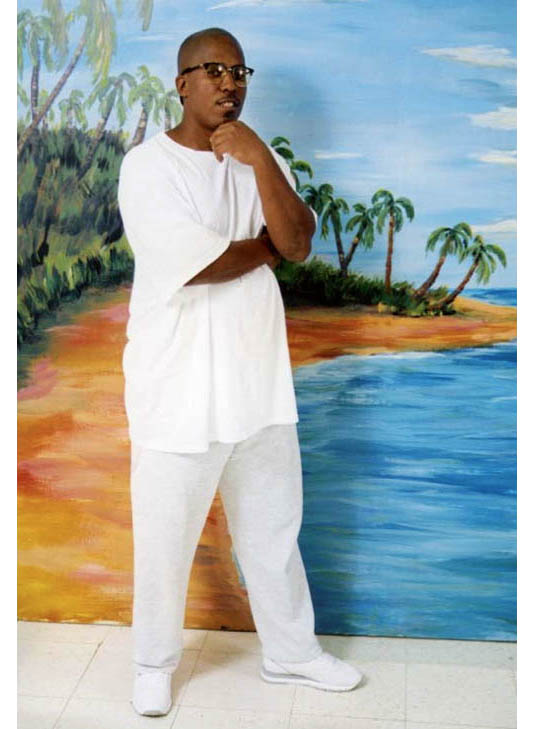

[Image:  [Image: James Bowlin, United States Penitentiary, Marion, Illinois; photograph courtesy

[Image: James Bowlin, United States Penitentiary, Marion, Illinois; photograph courtesy  [Image: Prison Visiting Room Backdrop, Shawangunk Correctional Facility, New York; photograph by

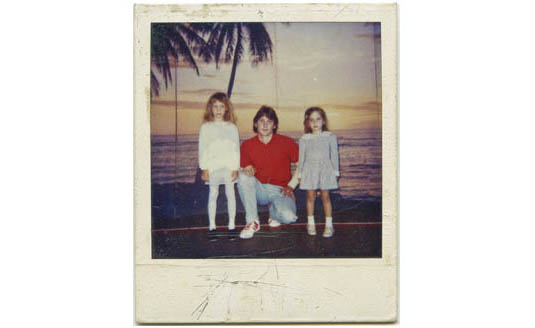

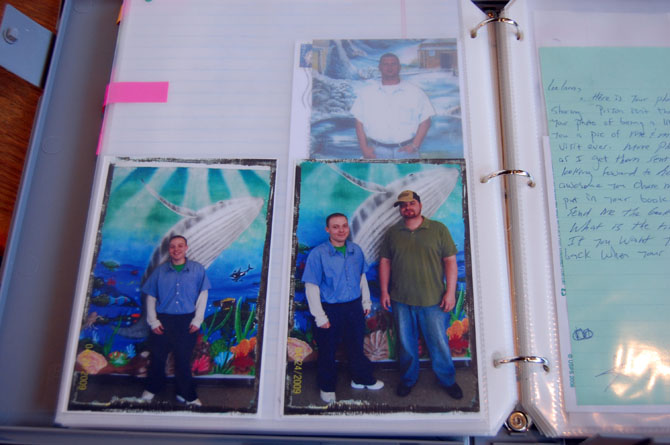

[Image: Prison Visiting Room Backdrop, Shawangunk Correctional Facility, New York; photograph by  [Image: Emdur family photo in front of prison visiting room backdrop; photograph courtesy

[Image: Emdur family photo in front of prison visiting room backdrop; photograph courtesy  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

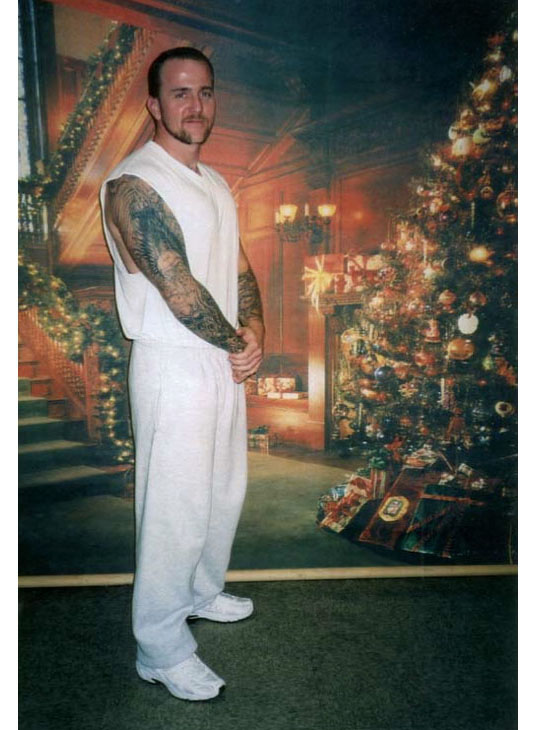

[Image:  [Image: Brandon Jones, United States Penitentiary, Marion, Illinois; photograph courtesy

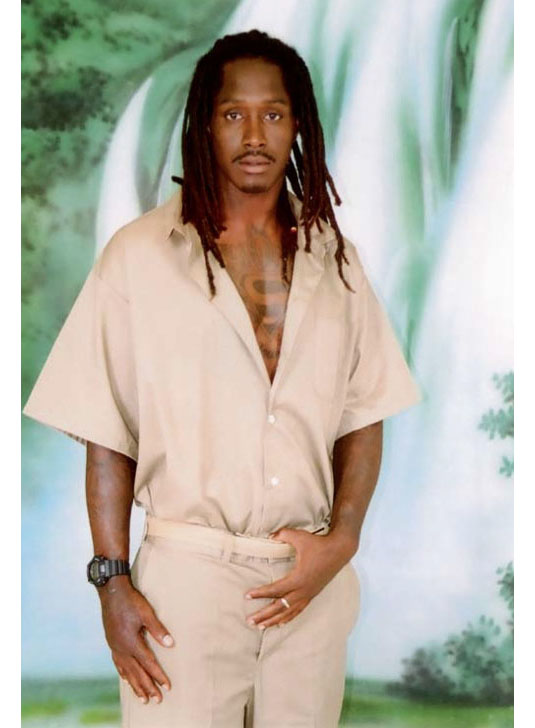

[Image: Brandon Jones, United States Penitentiary, Marion, Illinois; photograph courtesy  [Image: Genesis Asiatic, Powhatan Correctional Center, Statefarm, Virginia; photograph courtesy

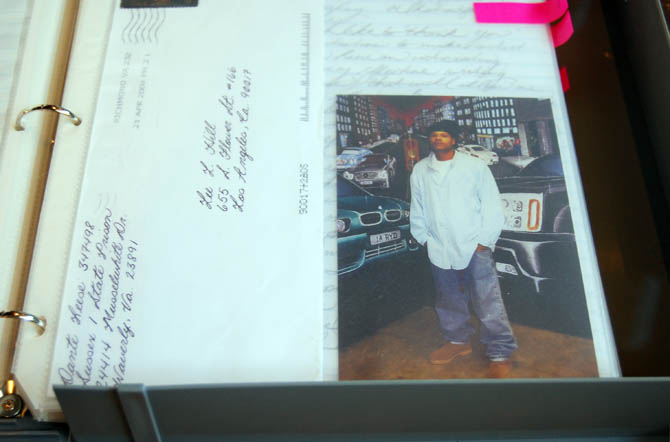

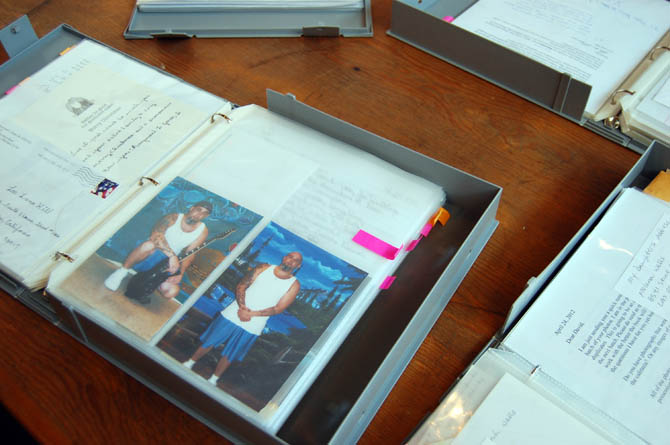

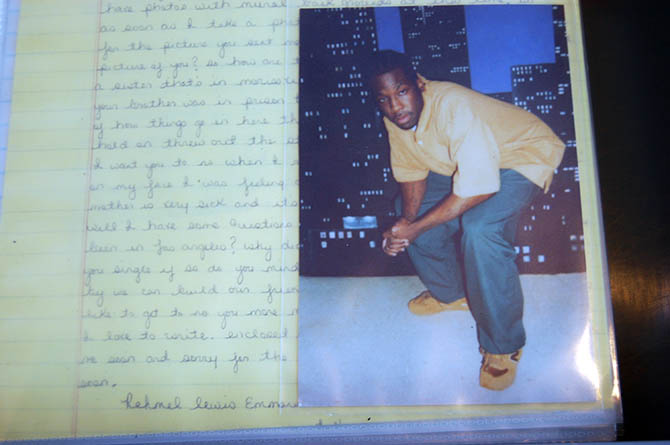

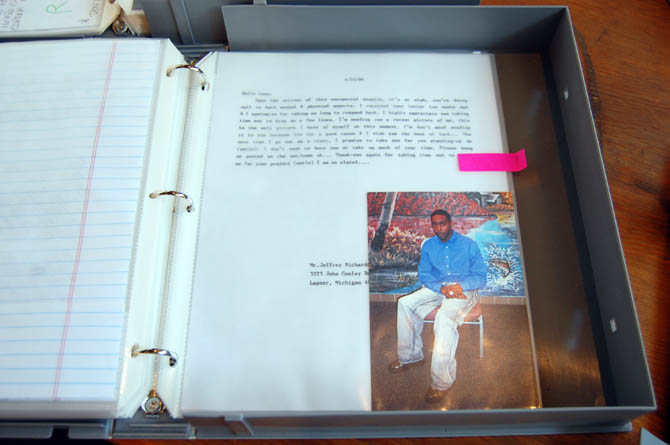

[Image: Genesis Asiatic, Powhatan Correctional Center, Statefarm, Virginia; photograph courtesy  One of sixteen binders full of letters and prisoner portraits mailed to

One of sixteen binders full of letters and prisoner portraits mailed to  [Image: Small prints of

[Image: Small prints of  [Image: Antoine Ealy, Federal Correctional Complex, Coleman, Florida; photograph courtesy

[Image: Antoine Ealy, Federal Correctional Complex, Coleman, Florida; photograph courtesy  [Image: Robert RuffBey, United States Penitentiary, Atlanta, Georgia; photograph courtesy

[Image: Robert RuffBey, United States Penitentiary, Atlanta, Georgia; photograph courtesy  [Image: One of sixteen binders full of letters and prisoner portraits mailed to

[Image: One of sixteen binders full of letters and prisoner portraits mailed to  [Image: Kimberly Buntyn, Valley State Prison for Women, Chowchilla, California; photograph courtesy

[Image: Kimberly Buntyn, Valley State Prison for Women, Chowchilla, California; photograph courtesy

[Images: Sixteen binders’ worth of letters and prisoner portraits have been mailed to Emdur over the course of her project; photographs by

[Images: Sixteen binders’ worth of letters and prisoner portraits have been mailed to Emdur over the course of her project; photographs by  [Image: A binder of letters and prisoner portraits mailed to

[Image: A binder of letters and prisoner portraits mailed to

[Image:

[Image:

[Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Images: From “

[Images: From “ [Images: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “

[Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “ [Images: From “

[Images: From “

[Image: “Santissima Trinidad (Iturgoyen)” by

[Image: “Santissima Trinidad (Iturgoyen)” by

[Images: (top) “Nuestra Señora de los Dolores (Monflorite)” and (bottom) “Nuestra Señora de las Viñas (Quintanilla de las Viñas)” by

[Images: (top) “Nuestra Señora de los Dolores (Monflorite)” and (bottom) “Nuestra Señora de las Viñas (Quintanilla de las Viñas)” by  [Image: “San Juan Bautista (Barbadillo del Mercato)” by

[Image: “San Juan Bautista (Barbadillo del Mercato)” by

[Images: (top) “San Juan de Busa (Larrède),” (middle) “Virgen de Berzosa (Palazuelos de Villadiego),” and (bottom) “Nuestra Señora de las Viñas (Quintanilla de las Viñas)” by

[Images: (top) “San Juan de Busa (Larrède),” (middle) “Virgen de Berzosa (Palazuelos de Villadiego),” and (bottom) “Nuestra Señora de las Viñas (Quintanilla de las Viñas)” by

[Images: (top) “San Vicente (Cervera de Pisuerga),” (middle) “Virgen del Vallejo (Alcozar),” and (bottom) “Virgen del Carmén (Cadalso)” by

[Images: (top) “San Vicente (Cervera de Pisuerga),” (middle) “Virgen del Vallejo (Alcozar),” and (bottom) “Virgen del Carmén (Cadalso)” by  [Image: “San Millan (Velilla de los Ajos)” by

[Image: “San Millan (Velilla de los Ajos)” by  [Image: “San Bartolomé (Ucero)” by

[Image: “San Bartolomé (Ucero)” by  [Image: “Shopping mall parking lot, Dubai,” (2009) by Bas Princen].

[Image: “Shopping mall parking lot, Dubai,” (2009) by Bas Princen]. [Image: “Cooling plant, Dubai,” (2009) by Bas Princen].

[Image: “Cooling plant, Dubai,” (2009) by Bas Princen].  [Image: “Sand ridge, Amman,” (2009) by Bas Princen].

[Image: “Sand ridge, Amman,” (2009) by Bas Princen].

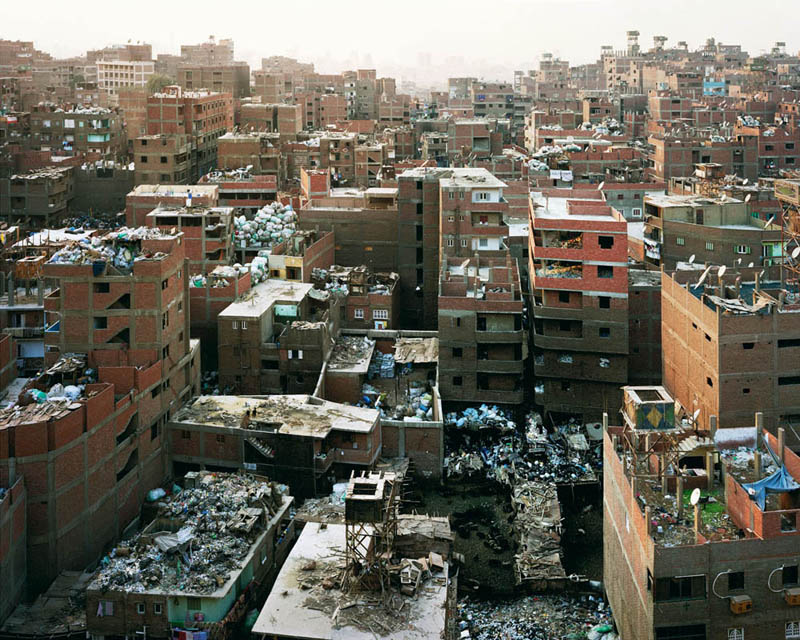

[Images: “Former sugarcane field, Cairo,” (2009) and “Ringroad, Cairo,” (2009) by Bas Princen].

[Images: “Former sugarcane field, Cairo,” (2009) and “Ringroad, Cairo,” (2009) by Bas Princen]. [Images: “Mokkatam Ridge (garbage recycling city), Cairo,” (2009) by Bas Princen].

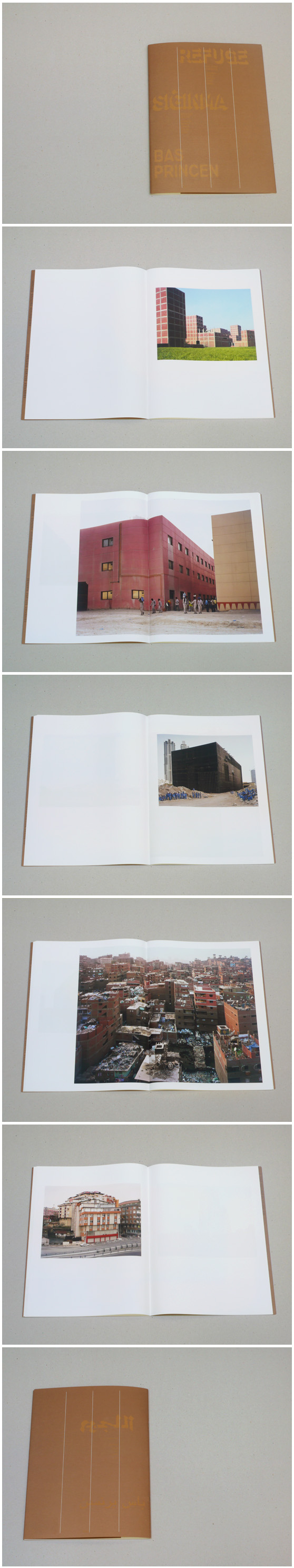

[Images: “Mokkatam Ridge (garbage recycling city), Cairo,” (2009) by Bas Princen]. [Images: Spreads from “

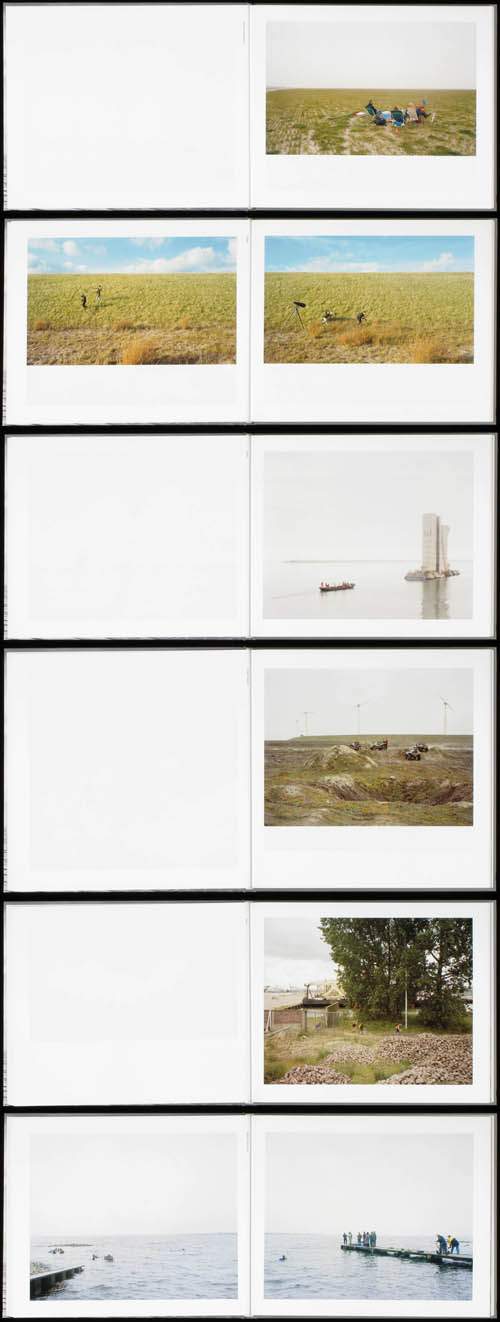

[Images: Spreads from “ [Images: Spreads from

[Images: Spreads from  [Image: “Valley, Beirut,” (2009) by Bas Princen, from “

[Image: “Valley, Beirut,” (2009) by Bas Princen, from “ [Image: The Pelican Nebula, photographed by Charles Shahar at the

[Image: The Pelican Nebula, photographed by Charles Shahar at the  [Image: John Constable, Seascape Study with Rain Cloud (1827); originally spotted at

[Image: John Constable, Seascape Study with Rain Cloud (1827); originally spotted at

[Images: (top) The bewilderingly beautiful Cat’s Paw Nebula, photographed by T.A. Rector at the University of Alaska, Anchorage; (middle) The Witch Head Nebula, photographed by Davide De Martin at the Palomar Observatory; (bottom) The Rosette Nebula, photographed by J.C. Cuillandre (Canada France Hawaii Telescope) and Giovanni Anselmi (Coelum Astronomia)].

[Images: (top) The bewilderingly beautiful Cat’s Paw Nebula, photographed by T.A. Rector at the University of Alaska, Anchorage; (middle) The Witch Head Nebula, photographed by Davide De Martin at the Palomar Observatory; (bottom) The Rosette Nebula, photographed by J.C. Cuillandre (Canada France Hawaii Telescope) and Giovanni Anselmi (Coelum Astronomia)]. [Image: “C-47 Alberta” by

[Image: “C-47 Alberta” by  [Image: “C-47 Yukon” by

[Image: “C-47 Yukon” by  [Image: “C-47 Crows Nest Pass” by

[Image: “C-47 Crows Nest Pass” by  [Image: “727 Santa Domingo” by

[Image: “727 Santa Domingo” by  [Image: Das Eismeer (1823-24) by

[Image: Das Eismeer (1823-24) by

[Images: (top) “C-47 Beaver Creek” and (bottom) “C-47 Snag” by

[Images: (top) “C-47 Beaver Creek” and (bottom) “C-47 Snag” by  [Image: “Curtiss Commando Patagonia” by

[Image: “Curtiss Commando Patagonia” by

[Images: “Miss Piggy Churchill” 1 and 2 by

[Images: “Miss Piggy Churchill” 1 and 2 by  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: “Daechi Dong,” a photo by

[Image: “Daechi Dong,” a photo by

[Images: “Howon Dong” and “Sinbong Dong 2,” photos by

[Images: “Howon Dong” and “Sinbong Dong 2,” photos by

[Images: “Samsung Dong” and “Uman Dong,” photos by

[Images: “Samsung Dong” and “Uman Dong,” photos by  [Image: “Sindorim Dong” by

[Image: “Sindorim Dong” by

[Images: “Jangan Dong” and “Sinbong Dong,” photos by

[Images: “Jangan Dong” and “Sinbong Dong,” photos by