A few weeks ago, The Economist looked at the growing problem of “ubiquitous technical surveillance” in the field of espionage. It describes the difficulty of maintaining a rigorous or believable cover story, for example, when genealogy websites might be consulted by adversarial border agents to verify that a potential spy is who she says she is, where internet cookies and undeleted search histories might reveal a hidden identity, or, of course, when fitness trackers, smartphones, and other networked devices specifically exist for the purpose of recording our current locations and recent activities. We now pay to be tracked, then seek self-awareness in the data.

I’ll admit, however, that I was expecting the Economist article to go into a bit more detail about the ubiquitous tech part of its headline. That is, we are living through the rise of an immersive, real-time, omnipresent environment of always-on sensors that are now coextensive both with urban space and with modern transportation infrastructure, from airports to ride-sharing apps. The article does refer to techniques such as “retroactive surveillance,” whereby an intelligence agency, investigative team, or police authority can spool backward in time, so to speak, following every move you made prior to arriving at a particular moment or destination; but, again, I think there’s more to be said about the fact that the built environment itself is, for all intents and purposes, becoming a gigantic archive, at all scales, forensically recording every event that occurs within it, with few or no options for opting out.

The recent story of the Coldplay concert kiss-cam is only one superficial example of how commercial experiences are now all but premised on the possibility of being archived, from the cameras in strangers’ pockets to all-seeing eyes like the one that caught a cheating couple mid-embrace. Indeed, being caught on camera is often presented now as one of the main highlights of attending a concert or sports event in the first place: looking up through a haze of light and anonymity to see your own face on a gigantic screen, then raising your arms and cheering, because the lottery of public surveillance has found you, momentarily pulling you out of the crowd and giving your life a taste of communal validation. For three seconds, you are the star. This is ubiquitous technical surveillance as both promise and thrill.

Again, though, cameras and such like are only the most superficial recording technologies at work. Recall that underground fiber-optic cable networks can also be tapped as seismic sensors, recording vehicle traffic and pedestrian footfall (and, in some cases, private conversations) or that smartphone accelerometers, networked microphones, and even self-driving vehicles are now recording not just our facial expressions but our vibrations and bodily movements.

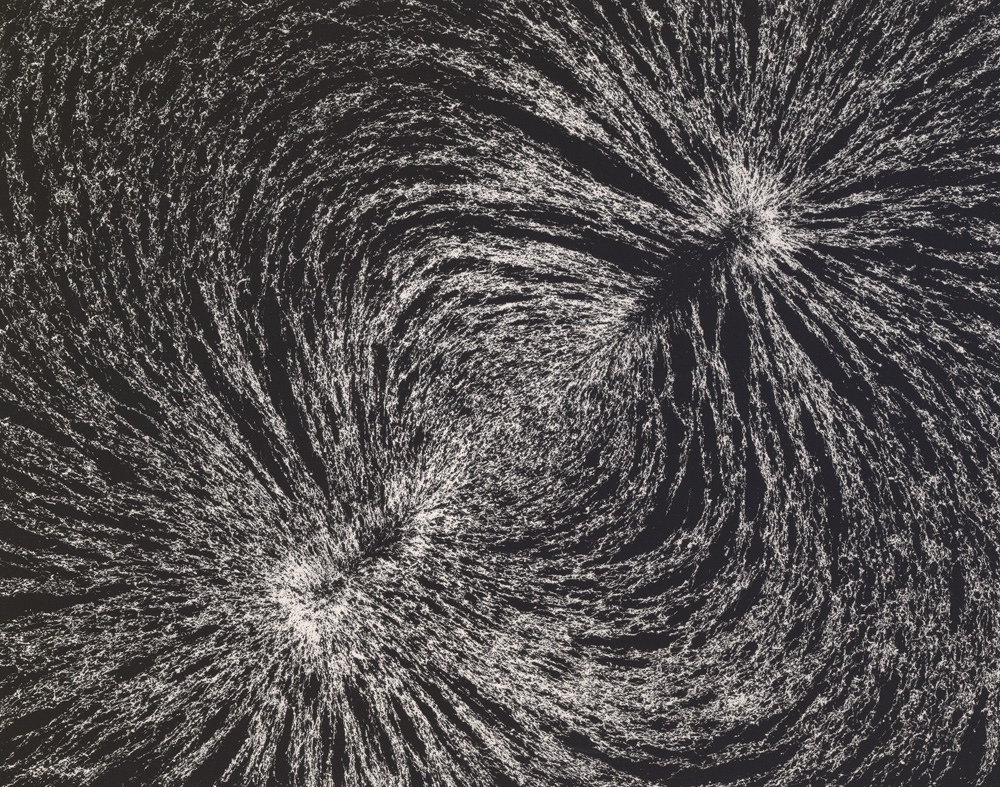

To this can be added much longer-term recording processes, something I’m exploring in a new book project, whereby our everyday activities also often, if unintentionally, leave behind archaeologically legible electromagnetic traces. The ubiquitous technical surveillance The Economist discusses becomes intergenerational. A single campfire in a field somewhere can leave a magnetic trace in the soil that lasts centuries, even millennia.

It is often presented as a reason for nihilism or melancholy, that our lives are ultimately fleeting, insubstantial, and almost certainly destined for oblivion, leaving behind nothing to remember or memorialize us; but I think there’s a much stranger fate taking shape at the moment, which is that, no matter what we do, it is as if we cannot disappear. We can always be found. We, in a sense, cannot be left behind; we will always be remembered and carried along with everyone else—a statement that perhaps once inspired reassurance and comfort, even cultural cohesion, but increasingly feels like an authoritarian threat.

[Images: Jace Clayton at work; photos by

[Images: Jace Clayton at work; photos by

[Image:

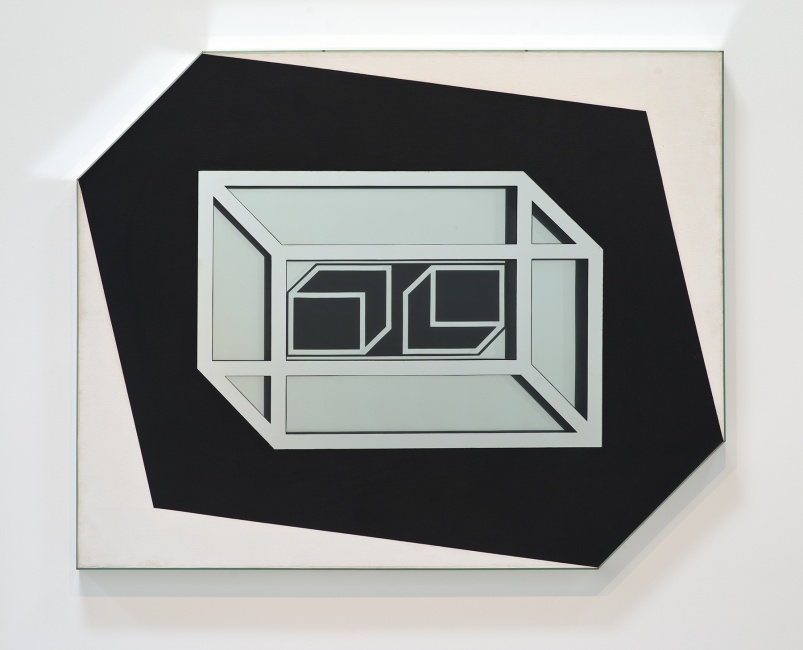

[Image:  [Image: “Untitled” by Larry Bell (1962), via the

[Image: “Untitled” by Larry Bell (1962), via the  [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: Geometry in the sky. “Diagram showing conceptual photographs of how

[Image: Geometry in the sky. “Diagram showing conceptual photographs of how  [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: The “

[Image: The “