[Image: Pier Two Athletic Center by Maryann Thompson Architects, Brooklyn; via Architizer].

[Image: Pier Two Athletic Center by Maryann Thompson Architects, Brooklyn; via Architizer].

Unconventional sports…

A profile of Reebok published the other week on Bloomberg Business—which you needn’t read, unless you are really into either shoe design or the global fitness industry—there’s a brief but interesting observation about what people seem to want to do these days, in terms of physical activity.

Not exercise, as such—which is the wrong way to think about it—but physically moving through space together and having a good time.

The article points out the obvious, for example, that CrossFit is on the rise, and that things like Tough Mudders, Spartan Races, etc., are all gaining in popularity; to this, I would also add climbing, which—based on my own entirely unscientific observations—appears to be undergoing its own boom time, at least gauged by the madhouse of over-attendance you often see at local climbing gyms in the hour after school gets out, turning a place like my local Brooklyn Boulders into an awesome new kind of home away from home for many local teenagers.

The article calls these “unconventional sports,” and they don’t require the traditional gym set-up. They require unconventional spaces and landscapes.

This is thus at least partially a question of design.

[Image: Via Brooklyn Boulders].

[Image: Via Brooklyn Boulders].

…require unconventional spaces and landscapes

The new emphasis is on “social fitness,” the article claims—but I’d say that even that phrase misses the primary motivation, which is really just screwing around with your friends, doing something fun, extreme, memorable, a little crazy, and simply different.

It means something that gets your heart rate up, lets you run around or climb on things for no reason to blow off steam, and that turns your immediate spatial environment into a place of often berserk new physical opportunities—another way of saying that you can literally climb the walls.

It’s like The Purge meets phys ed—not just “exercise,” with all the moral overtones of such a misused word.

[Image: Via CrossFit].

[Image: Via CrossFit].

“We’ve seen a real shift in the fitness world away from using heavy equipment like treadmills and stair climbers and toward much more social, class-based fitness—Zumba, Pilates, yoga, CrossFit,” an analyst named Matt Powell explains to Bloomberg Business. “These activities are really ramping up. So for a brand to stake out the fitness activity as their cornerstone makes a lot of sense right now.”

He’s talking about Reebok exploring new shoe designs made specifically for CrossFit and other forms of unconventional training apparel—but I’m genuinely curious what the architectural implications are in such a shift. Put another way, if Reebok was an architecture firm in charge of high school gymnasiums, what would this corporate revelation do to their spatial products? If what people physically do together has shifted toward the social, how might school gyms follow suit?

This isn’t just idle, Archigram-meets-Gold’s-Gym speculation. It we want to reverse the utterly insane trend toward removing gym class from children’s educational experiences, then it’s 100-times more likely that we’ll be able to do so not by cracking the whip harder and turning schools into militarized boot camps, but by designing spatial environments in which kids can do the things they actually want to do, where “exercise” is just a beneficial side-effect.

Even if that means adding BMX tracks, parkour competitions, trapeze routines, or—why not?—afternoon mud fights.

[Image: Via Clif Bar].

[Image: Via Clif Bar].

“Recess has been reduced or eliminated in many schools”

As Kaiser Permanente has pointed out, “the trend line for physical activity and education in schools is headed downward. As of 2006, only 4 percent of elementary schools, 8 percent of middle schools, and 2 percent of high schools nationwide provided daily physical education. Even recess has been reduced or eliminated in many schools.” This is horrifying.

Yet, if you stop by a place like the aforementioned Brooklyn Boulders on a weeknight, you’ll see not only that the place is often packed with teenagers who are as stoked as hell to be out of the classroom, doing weird physical things together, but that, awesomely, it’s often the very kids most often stereotyped as not giving a crap about exercise who are there hanging out and literally climbing the walls.

How can it be that gym class—or, more broadly speaking, physical activities in American schools—are so out of touch with what kids actually want to do these days that kids need to make a bee-line to the nearest climbing gym to burn off all their energy?

Is this purely a liability issue—because everyone’s perfect angel might scrape a knee—or has there been a failure of spatial imagination amongst the people building gyms and playgrounds today?

[Images: Ray’s MTB].

[Images: Ray’s MTB].

Just think of the underground bike park in Louisville or even just a local skatepark—or, for that matter, any of the more youth-oriented playgrounds I wrote about a few years ago for Popular Science.

In fact, just the other week, my wife and I were learning how to do 40-foot high falls off of scaffolding inside a warehouse over in Greenpoint as part of this random stunt-training thing we did. We were in a cavernous room full of huge mats, climbing walls, an oversized trampoline, and all sorts of other random things, like swords—and, what do you know, but there were also tons of kids of there, from the genuinely young to teenagers going through the most awkward phase of teenagerness, and there was no evidence on display that we live in a world where kids don’t want to do weird physical things together.

In other words, most people do want to “get exercise,” as it is unfortunately and rather Calvinistically known; they just want to do in a way where it’s a side-effect of having fun.

[Images: “Mega Bike” at the Louisville Mega Cavern; photos courtesy Louisville Mega Cavern].

[Images: “Mega Bike” at the Louisville Mega Cavern; photos courtesy Louisville Mega Cavern].

“I will be multifaceted”

Outdoor design consultant Scott McGuire of The Mountain Lab said something really interesting in a long interview published here back in 2013. McGuire suggested that “sport specificity” is being thrown out the window these days in favor of a general state of pure physical activity. Or, in his words:

When I grew up, you were a surfer or you were a skater or you were a climber or you were a road biker. But kids today don’t think anything like that—they think, “I do all of those things! Why would I not be someone who is a skier who’s also into bouldering who’s taking up trail running and who competes in Wii dance competitions? Why can’t I be that person?” There’s a sense that I will be whoever I want to be, whenever—and, of course, I will be multifaceted.

McGuire went on to suggest, similar to the Bloomberg Business article cited above, that “this is a generation who don’t see why they can’t leave the trail, go to town, have lunch, and go to the skate park and skate all afternoon, and not change gear. But the outdoor industry is having a hard time reconciling that.”

But, crucially, architects are having a hard time reconciling that, too. The spatial environments currently being designed and built to foster “exercise,” or physically engaged play, today rarely correspond to the activities people seem most excited to pursue.

In fact, I’d suggest that this is part of a much larger narrative, one that includes the decline in interest in heavily formalized Olympic sports, where the rise of alternative activities, such as X Games, parkour, BMX, and skateboarding, are proof that something else could very well fill that niche, but our spatial environments are lagging too far behind.

[Image: The Lake Cunningham Regional Skatepark, via The Skateboarder Mag].

[Image: The Lake Cunningham Regional Skatepark, via The Skateboarder Mag].

Designing the gym of tomorrow

If at least part of the crisis in phys ed today is that school gyms are simply being built wrong, then the obvious next question would be: what should they really look like?

This is, among other things, an architectural problem: what sorts of physical activities have been designed out of the school environment—not to mention the city, the suburb, the home, or the office?

Conversely, what activities should the schools, gyms, and buildings of today actually foster or allow?

[Image: Hyundai Motors FC Clubhouse by Suh Architects, South Korea; via Architizer].

[Image: Hyundai Motors FC Clubhouse by Suh Architects, South Korea; via Architizer].

At the most mundane level, could the architecture of the school building itself somehow absorb or otherwise channel the infamous distractibility and hyper-activity of kids today into deliberately frivolous physical activities (that is, “exercise”)?

In other words, if it looks like those kids in the back of class are literally about to climb the walls from eating too much breakfast cereal, then why not let them? Put whole spiraling labyrinths of climbing walls and tunnels throughout the school, with mats and helmets everywhere, and make exploring these inner wilds a genuine reward for sitting still in class.

There is nothing radical in such an observation, but it is nonetheless a genuine and important social issue: how to inspire, not to mention architecturally encourage, intense physical activity at all ages.

It’s not just urban design that’s “making us fat,” which is, after all, just an overly moralizing way of saying that urban design doesn’t let us have fun. It’s the fact that almost none of our buildings, including our schools and playgrounds, have been built to allow the kinds of physical activities people actually want to engage in these days.

[Image: Aerial view of the Lake Cunningham Regional Skatepark].

[Image: Aerial view of the Lake Cunningham Regional Skatepark].

So, if we go back to the Reebok example from the very beginning of this post, we’ll find an architectural conversation hiding in the details. We see a company realizing that its products no longer correspond to what its potential consumers actually want to do, and then forcing itself to fundamentally redesign those products in order to reflect the needs of this overlooked market.

What is the architectural—or more broadly speaking spatial—equivalent of this, and what should the gyms, schools, and playgrounds of tomorrow actually look like?

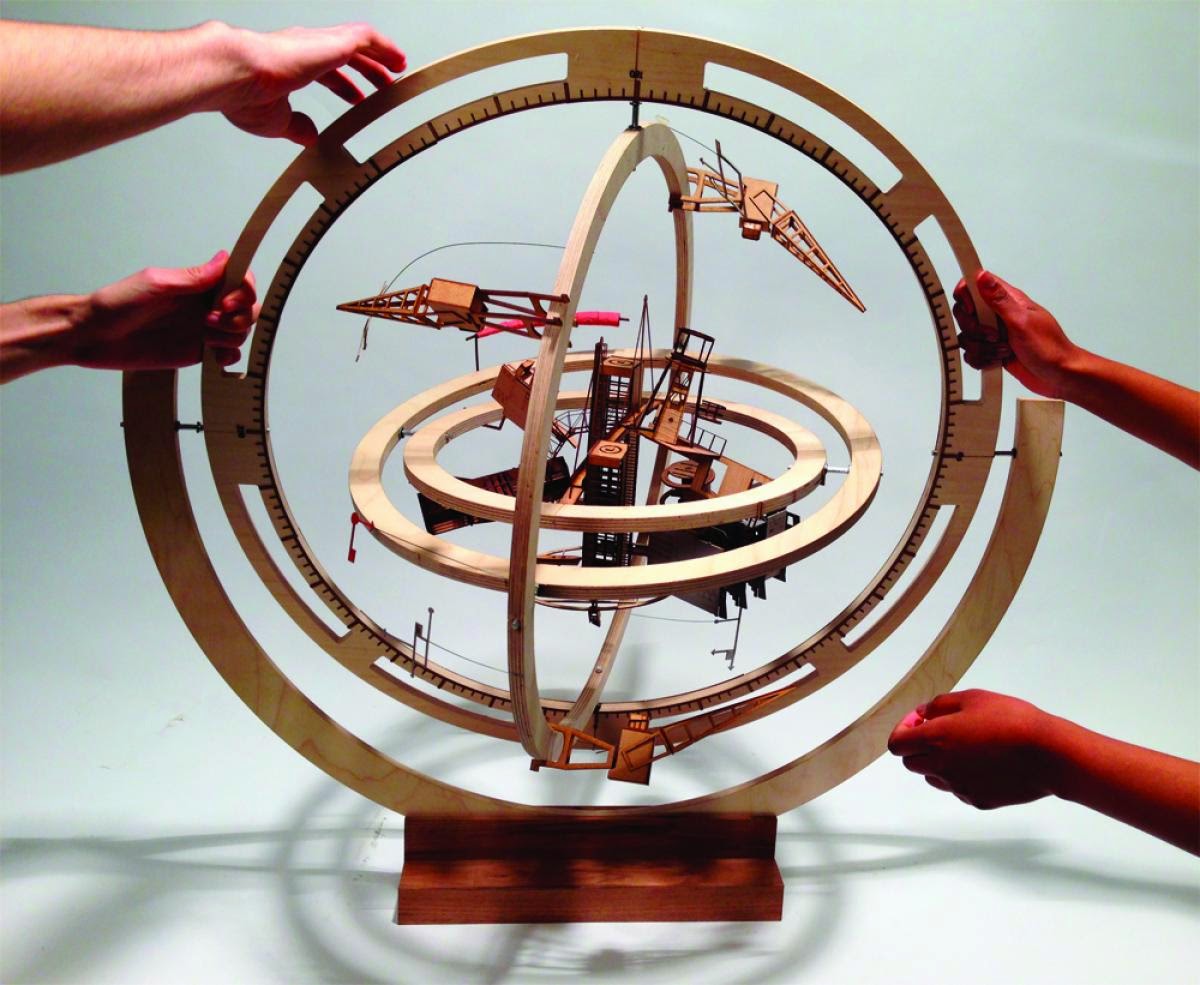

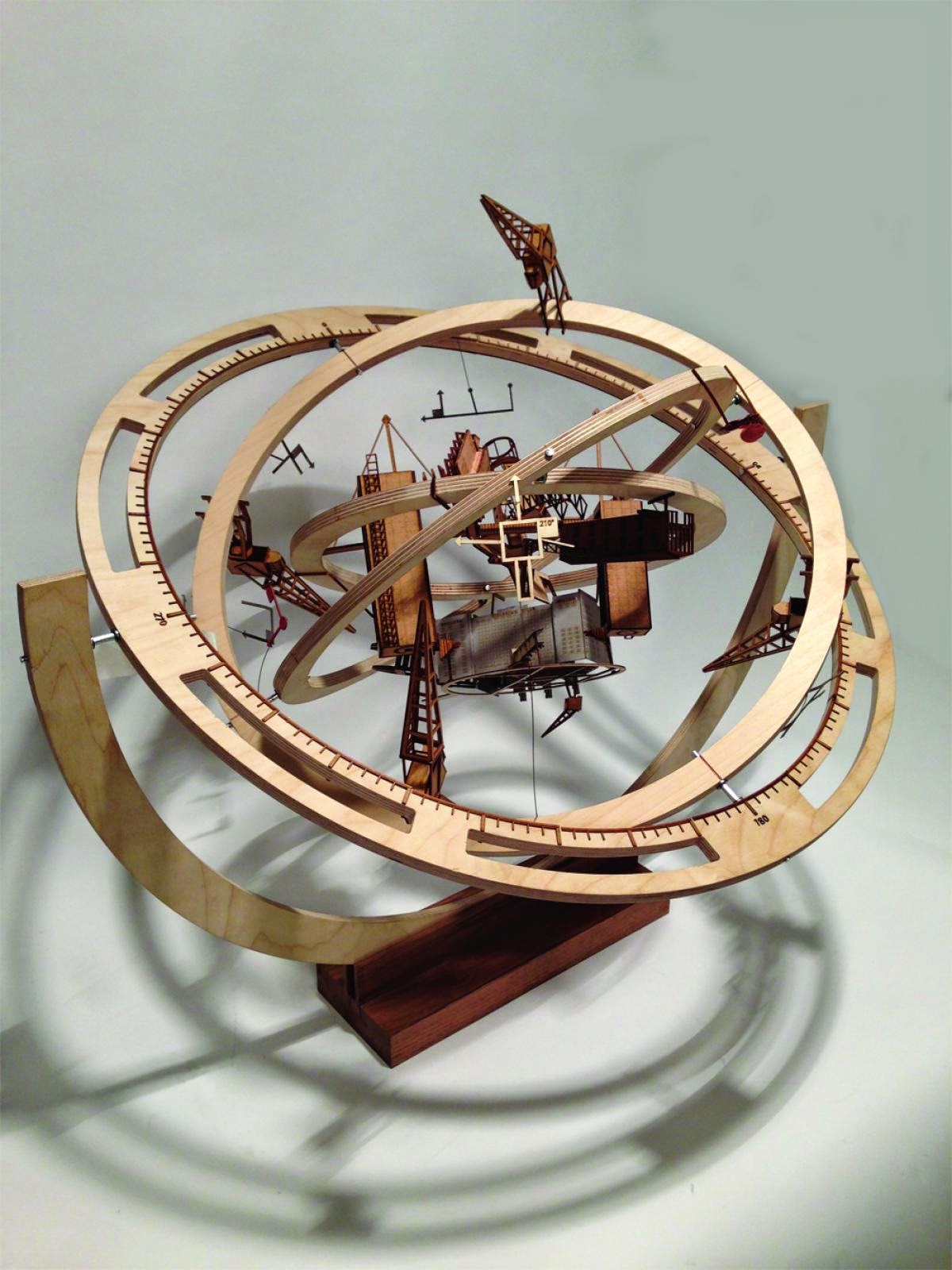

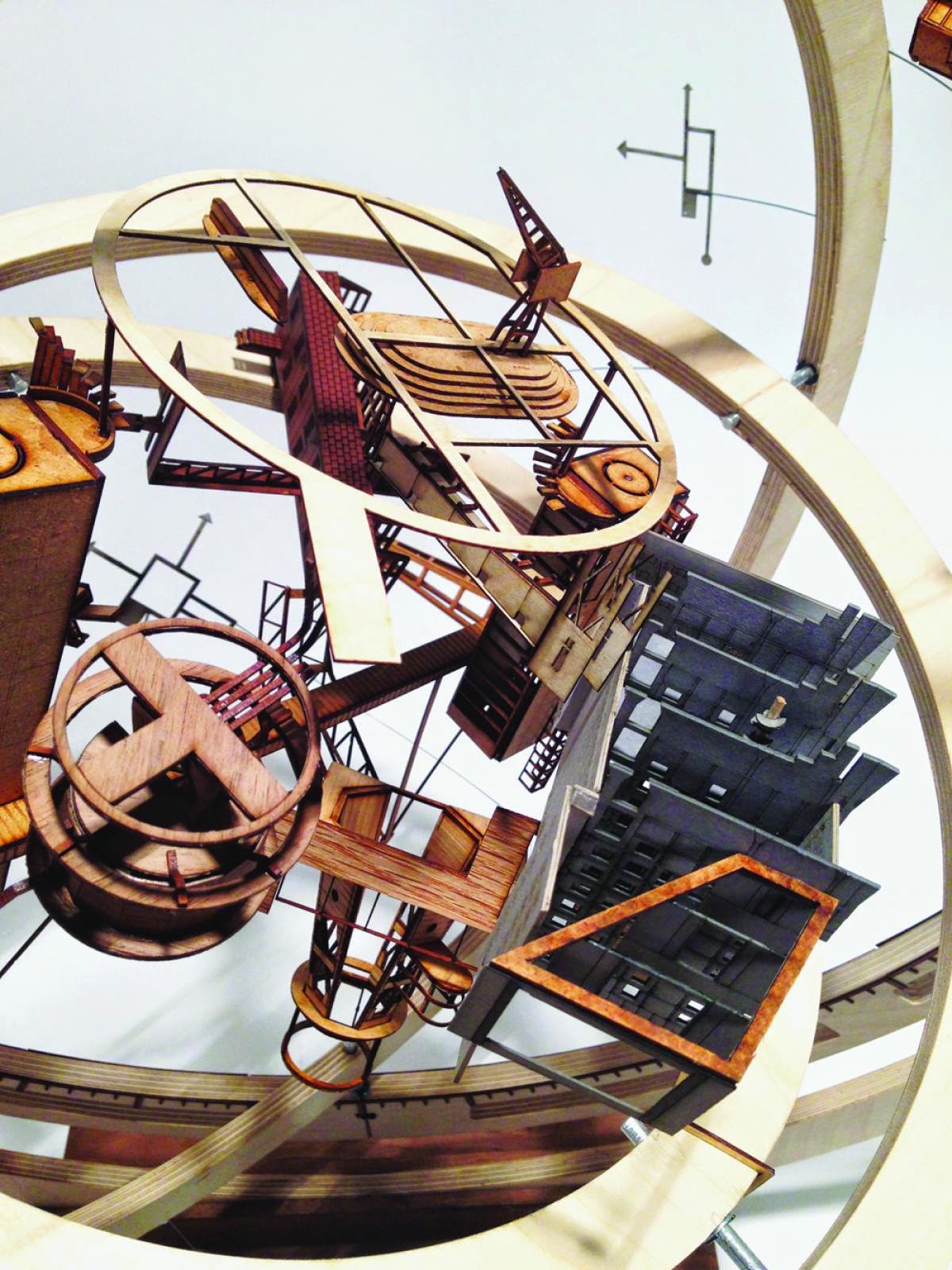

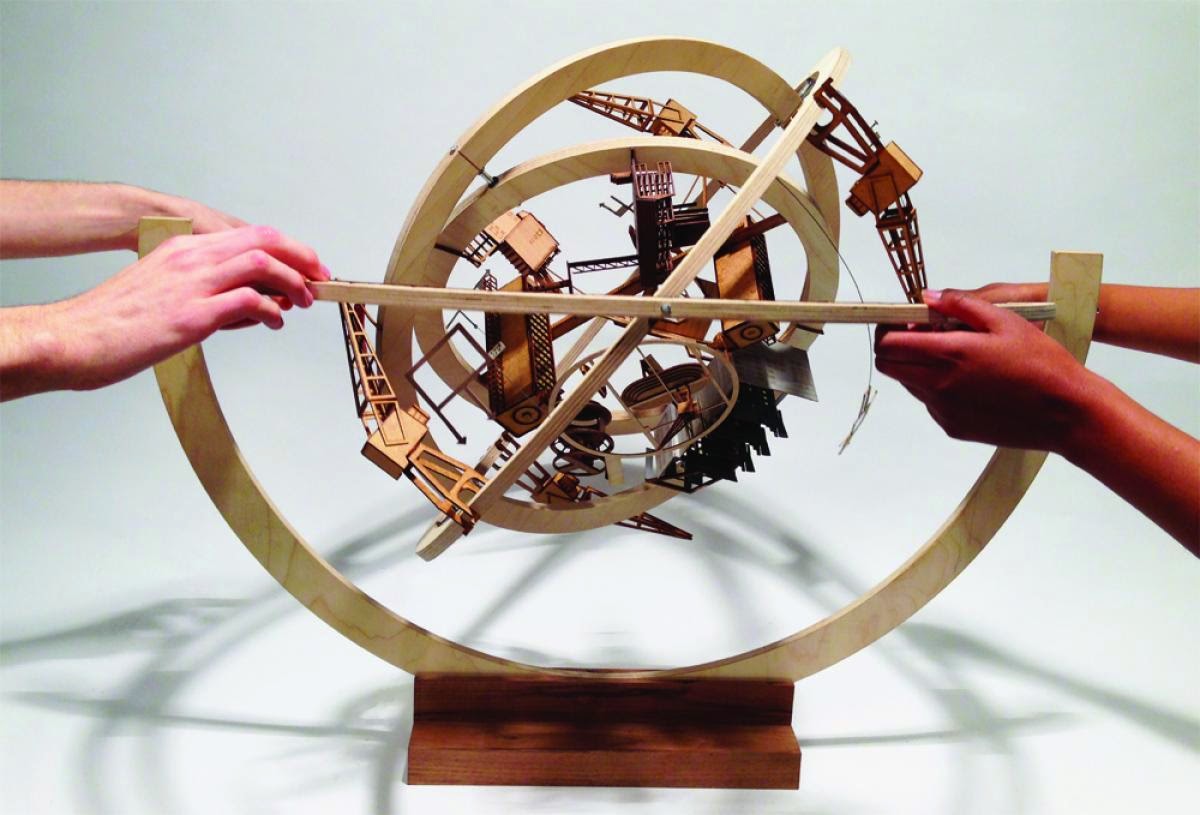

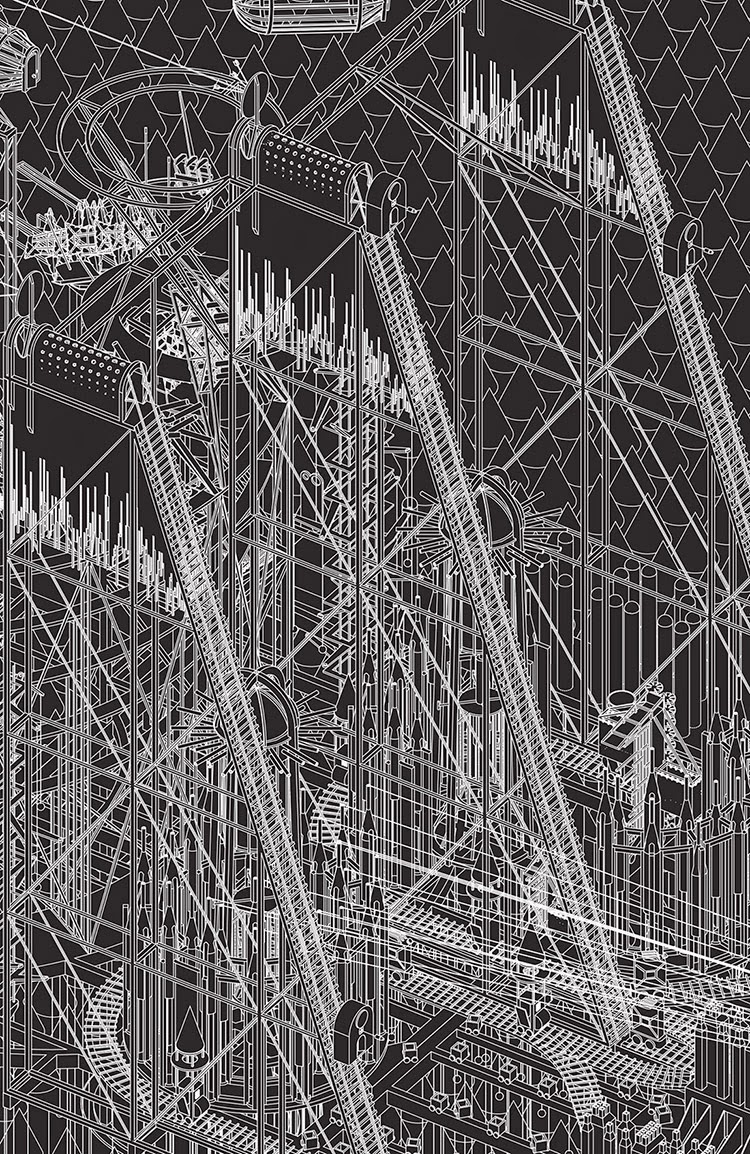

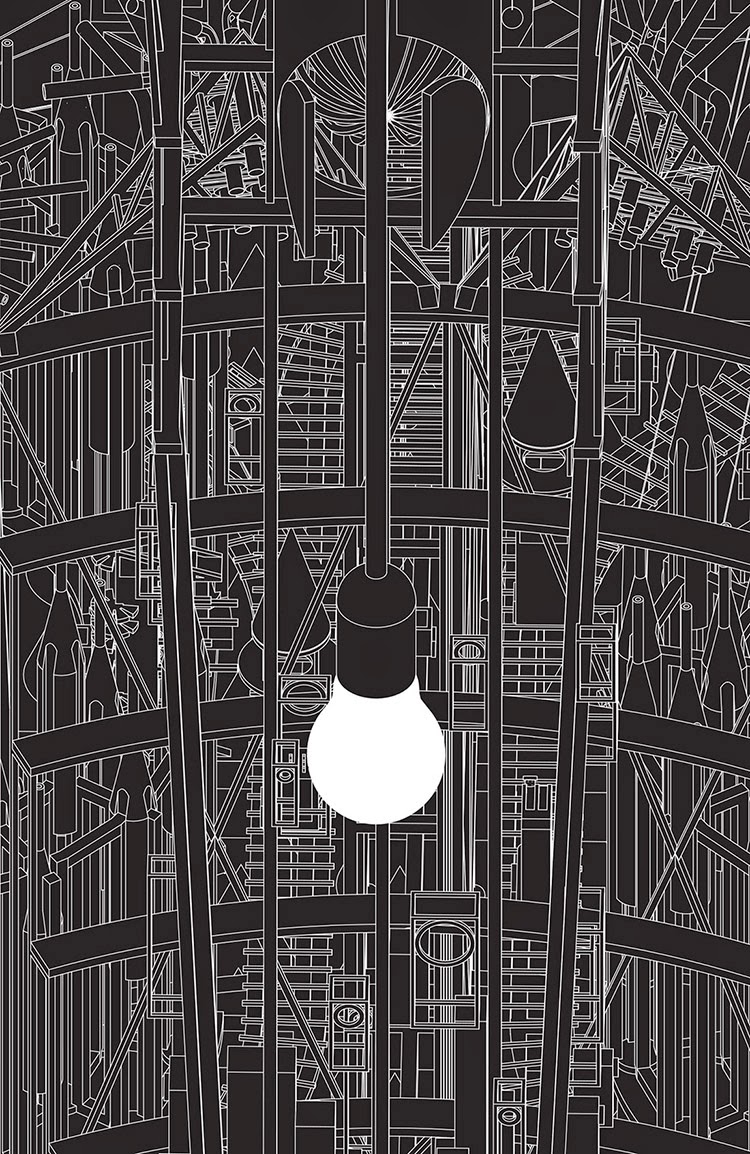

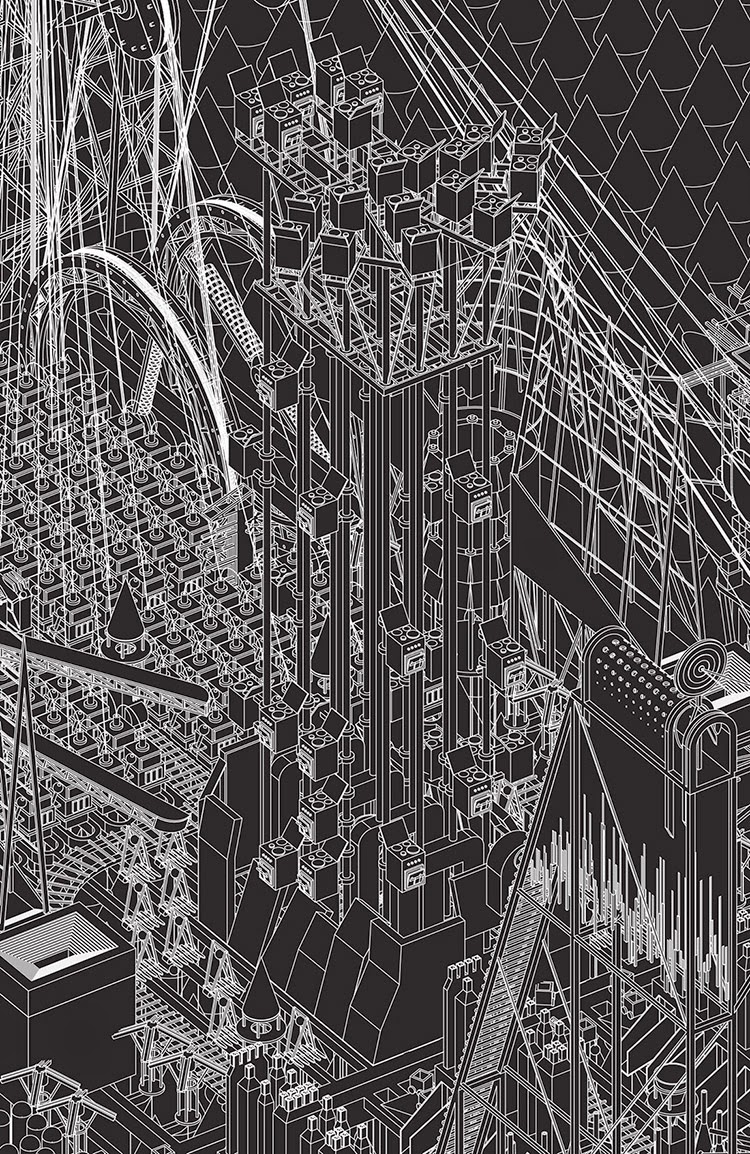

[Image: From “Destination Docklands” by Emma Colthurst; via Lobby].

[Image: From “Destination Docklands” by Emma Colthurst; via Lobby]. [Image: From “Destination Docklands” by Emma Colthurst].

[Image: From “Destination Docklands” by Emma Colthurst]. [Image: From “Destination Docklands” by Emma Colthurst].

[Image: From “Destination Docklands” by Emma Colthurst]. [Image: From “Destination Docklands” by Emma Colthurst].

[Image: From “Destination Docklands” by Emma Colthurst].

[Image: The “Vanessa School” (1973) by Fitch and Co., a retail design firm run by

[Image: The “Vanessa School” (1973) by Fitch and Co., a retail design firm run by

[Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: A “

[Image: A “ [Image: “

[Image: “

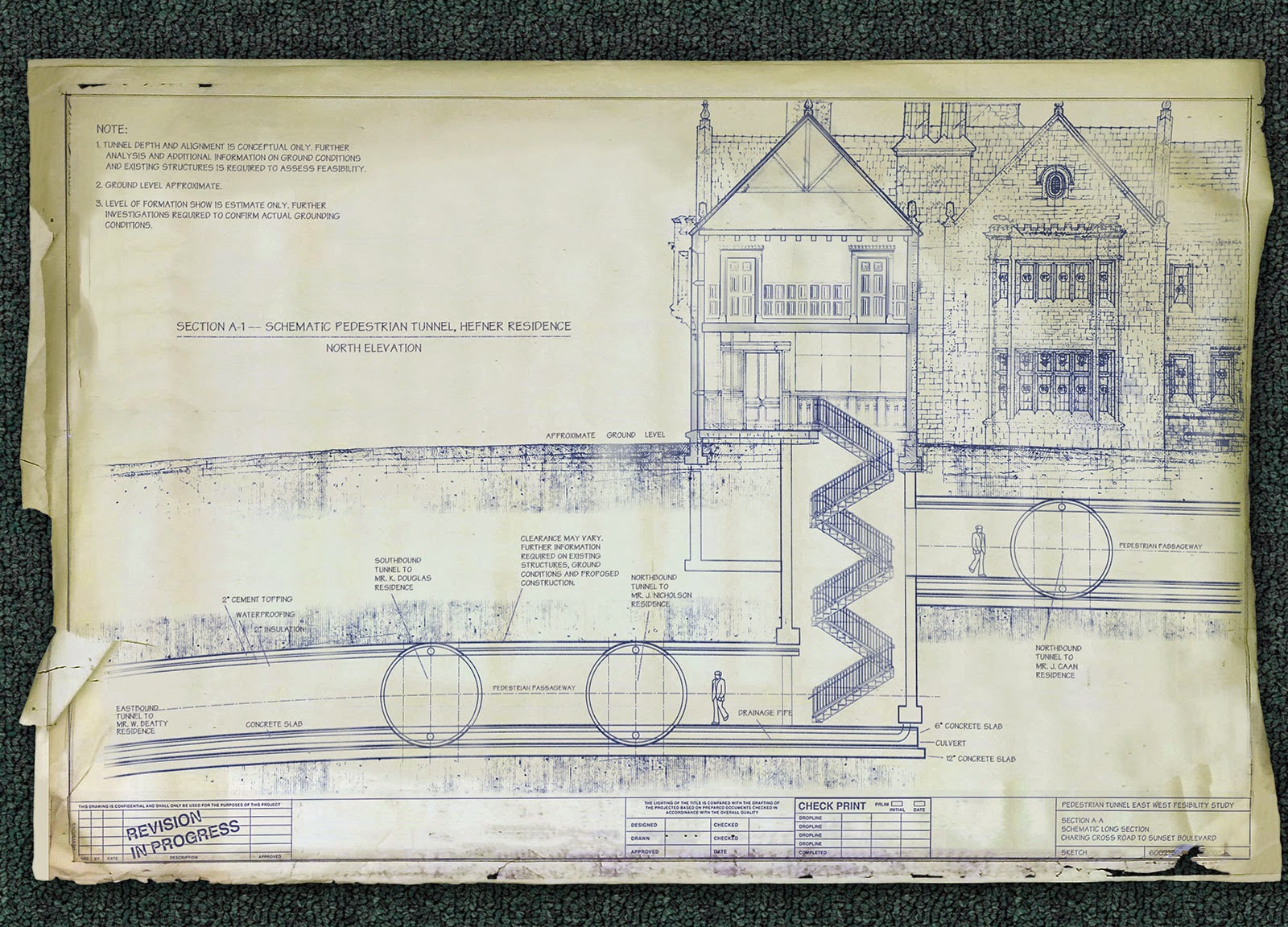

[Image: A blueprint of tunnels rumored to connect the Playboy Mansion with nearby celebrity homes, via

[Image: A blueprint of tunnels rumored to connect the Playboy Mansion with nearby celebrity homes, via

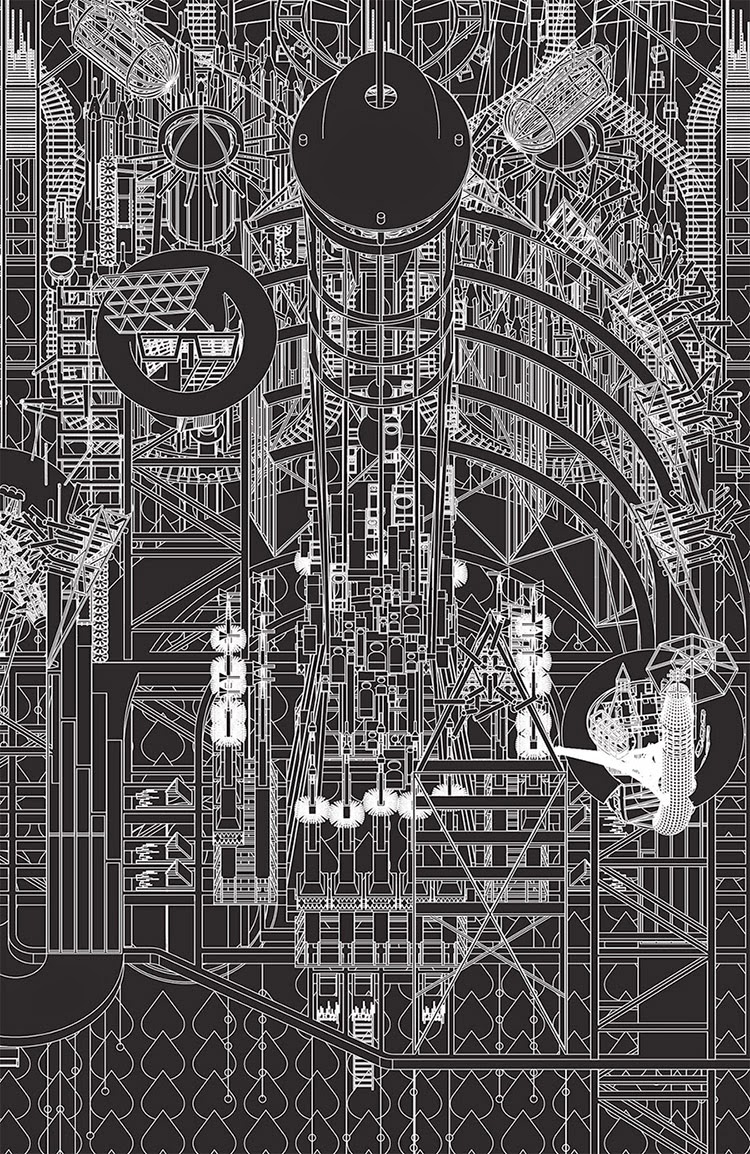

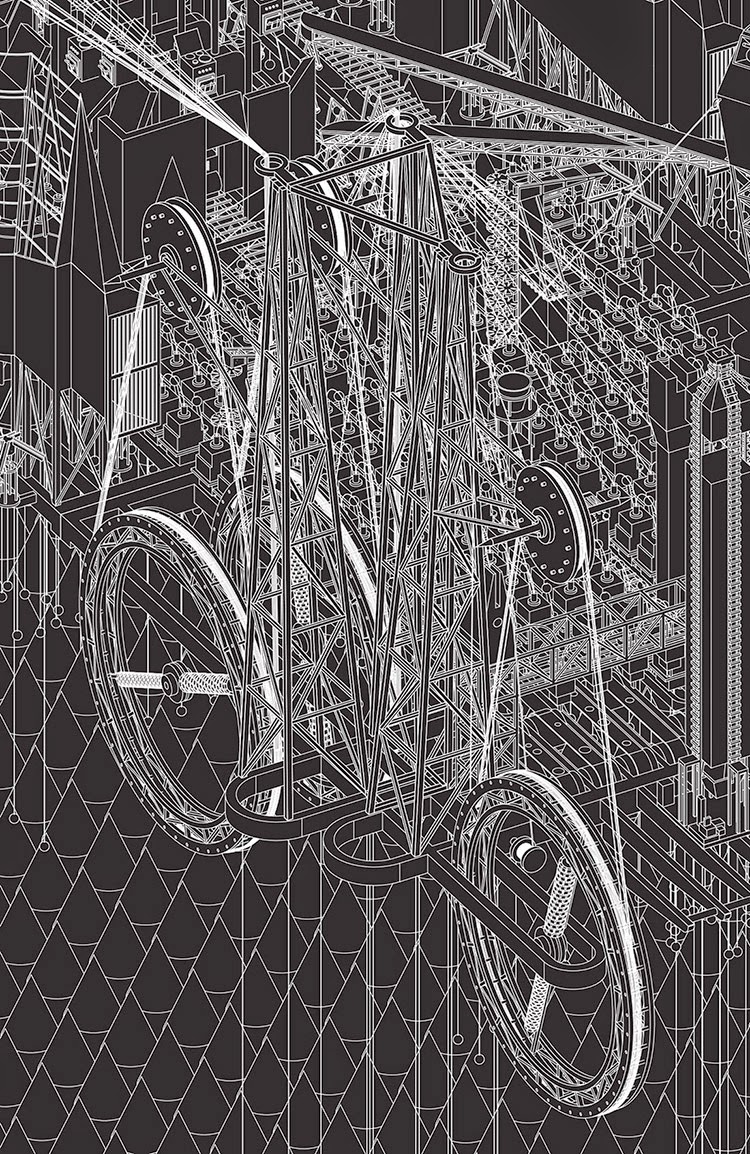

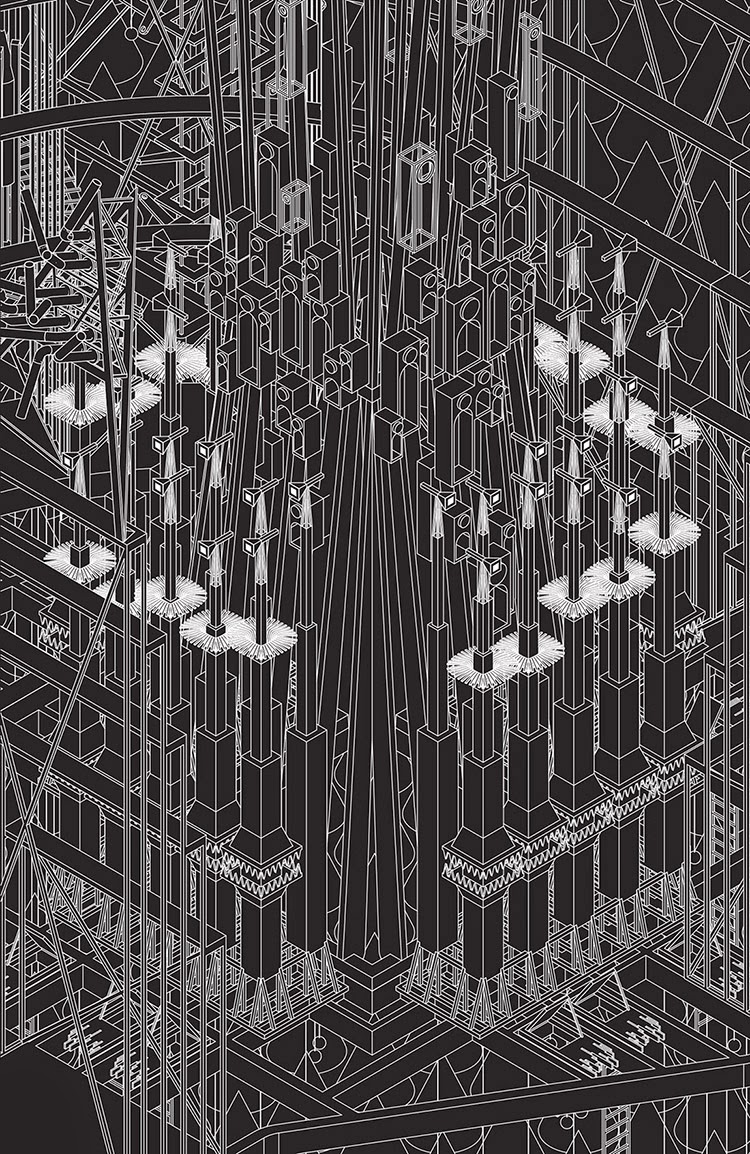

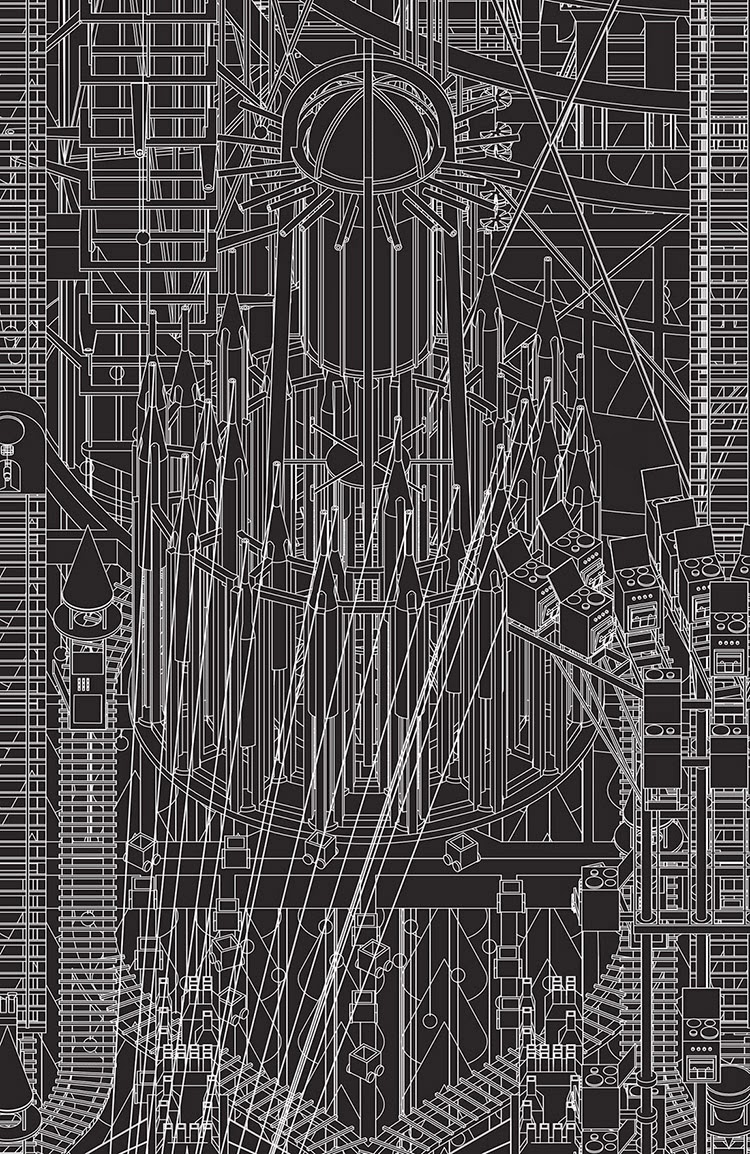

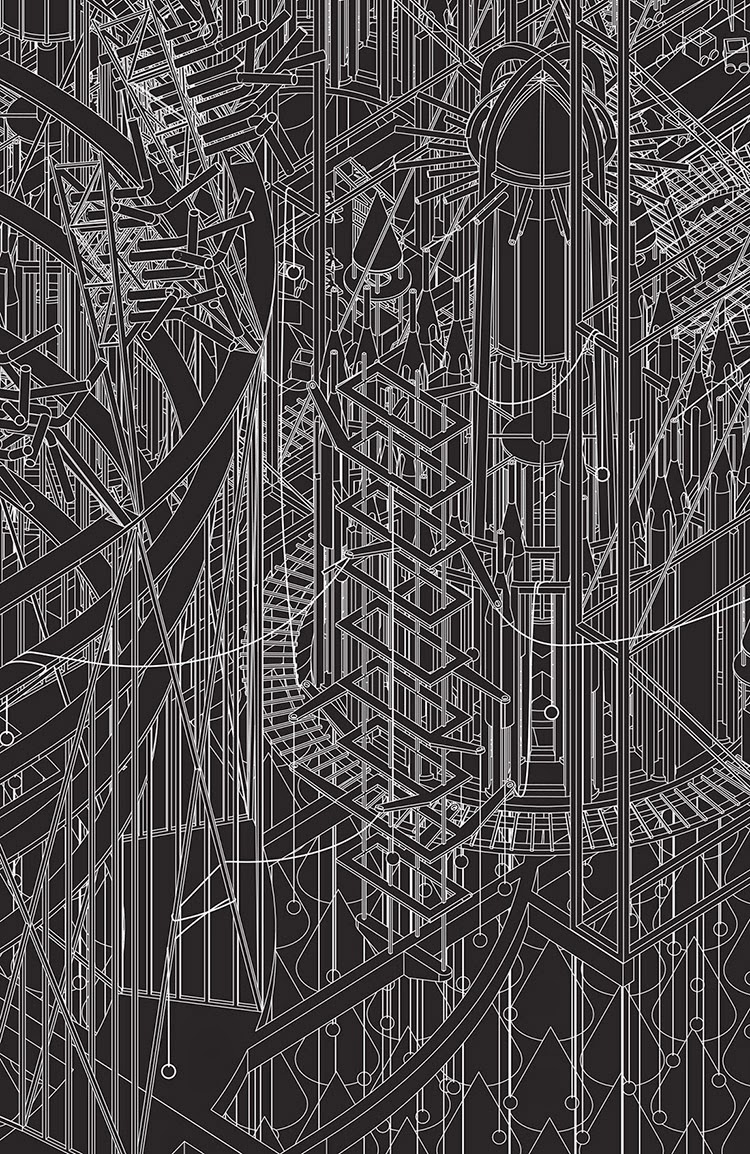

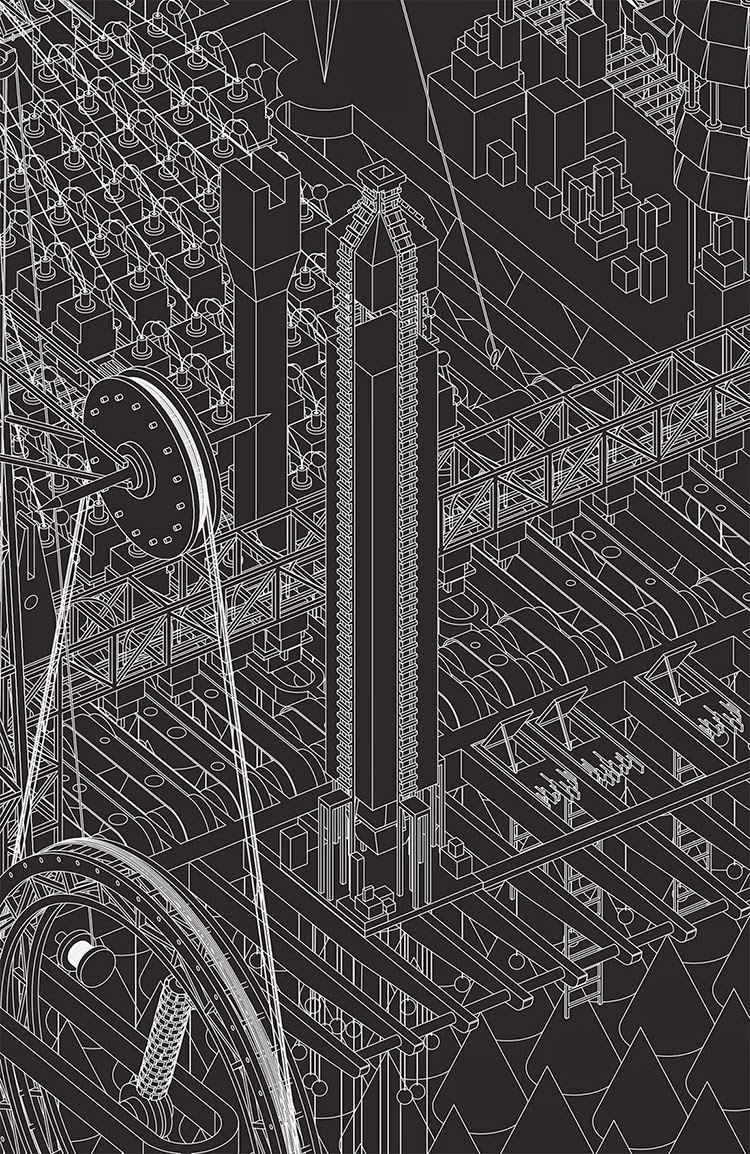

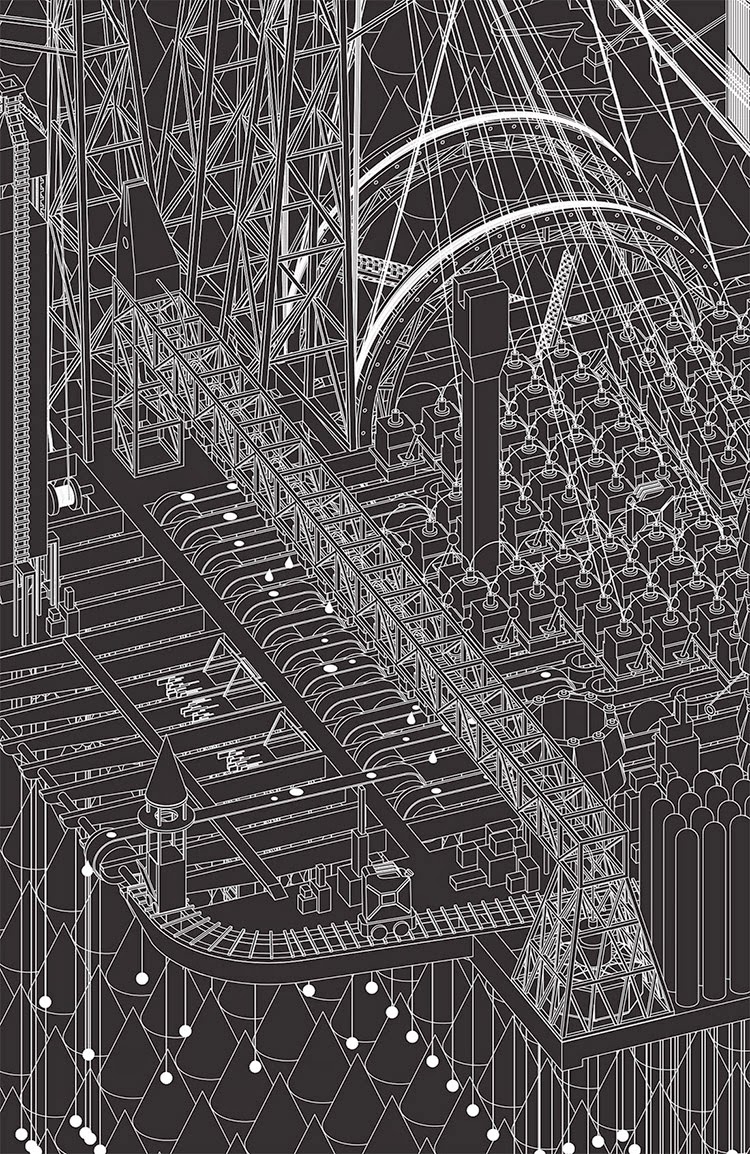

[Image: Grimm City University from Grimm City by

[Image: Grimm City University from Grimm City by  [Image: The Barometer from Grimm City by

[Image: The Barometer from Grimm City by  [Image: The Bremen Town-Musicians from Grimm City by

[Image: The Bremen Town-Musicians from Grimm City by

[Images: Two views of the Church and the neighboring Destruction Structure from Grimm City by

[Images: Two views of the Church and the neighboring Destruction Structure from Grimm City by  [Image: The Timber Factory from Grimm City by

[Image: The Timber Factory from Grimm City by  [Image: The Ink Factory from Grimm City by

[Image: The Ink Factory from Grimm City by  [Image: The Confession Booths from Grimm City by

[Image: The Confession Booths from Grimm City by  [Image: The Morning Star from Grimm City by

[Image: The Morning Star from Grimm City by  [Image: The Parliament from Grimm City by

[Image: The Parliament from Grimm City by

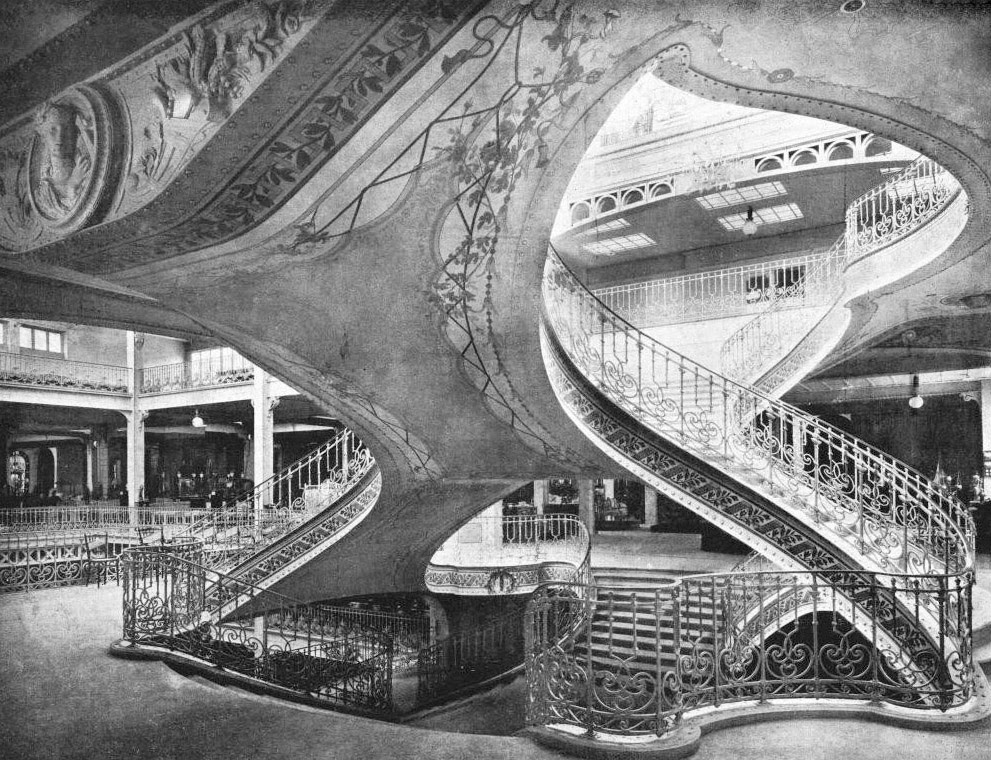

[Image: A staircase in the

[Image: A staircase in the

[Image: Stairs inside the New York Life Insurance building, Minneapolis, by

[Image: Stairs inside the New York Life Insurance building, Minneapolis, by

[Image: Unrealized proposal for a “Palace of Water and Light” (1940) designed by Pier Luigi Nervi for the never-held 1942 Universal Exhibition in Rome;

[Image: Unrealized proposal for a “Palace of Water and Light” (1940) designed by Pier Luigi Nervi for the never-held 1942 Universal Exhibition in Rome;

[Image: Pier Two Athletic Center by Maryann Thompson Architects, Brooklyn; via

[Image: Pier Two Athletic Center by Maryann Thompson Architects, Brooklyn; via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Images:

[Images:

[Images: “

[Images: “ [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: Hyundai Motors FC Clubhouse by Suh Architects, South Korea; via

[Image: Hyundai Motors FC Clubhouse by Suh Architects, South Korea; via  [Image: Aerial view of the

[Image: Aerial view of the

[Image: “

[Image: “