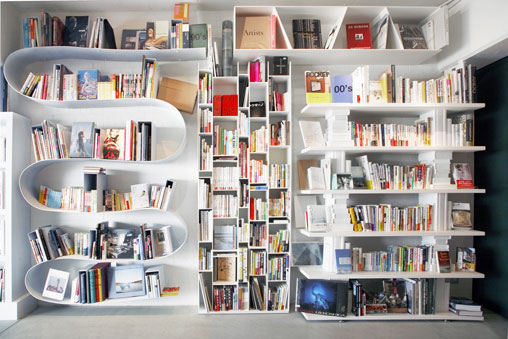

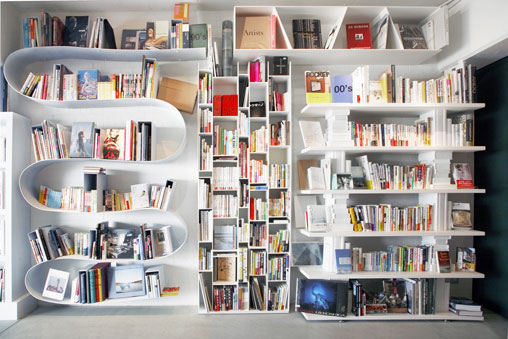

[Image: Bookstore for Shibuya Publishing, Japan, designed by Hiroshi Nakamura].

[Image: Bookstore for Shibuya Publishing, Japan, designed by Hiroshi Nakamura].

Through a combination of publisher review copies and the slow-to-end fire sale at my favorite local bookstore, Stacey’s – they’ve gone out of business and are selling everything at 50% off, including now even the furniture – BLDGBLOG’s home office is awash in books. Since there literally is not enough time left in a person’s life to read all of these, I decided that I would instead start a new, regular series of posts on the blog called “Books Received” – these will be short descriptions of, and links to, interesting books that have crossed my desk.

Note that these lists will include books I have not read in full – but they will never include books that don’t deserve the attention.

Note, as well, that if you yourself have a book you’d like to see on BLDGBLOG, get in touch – send us a copy, and, if it fits the site, we’ll mention your title in a future Books Received.

1) Oase #75 and #76 — Oase is an excellent architecture and urban studies journal published by the Netherlands Architecture Institute and designed by Karel Martens of Werkplaats Typografie. Oase #75 is the 25th anniversary issue, and includes essays from Jurjen Zeinstra (“Houses of the Future”), René Boomkens (“Modernism, Catastrophe and the Public Realm”), and Frans Sturkenboom (“Come una ola de fuerza y luz: On Borromini’s Naturalism”), among many, many others. To be honest, there is so much interesting material in this issue that it’s hard to know where to start; look for this in specialty architecture bookstores and definitely consider picking up a copy. Meanwhile, Oase #76 arrived just in time for me to quote part of its interview with photographer Bas Princen in The BLDGBLOG Book – but the entire issue, bilingually printed in both English and Dutch and themed around what the editors call “ContextSpecificity,” is worth reading. There’s a whole section on “In-Between Buildings,” itself coming between long looks at context, tradition, and the generation of architectural form. #76 also includes virtuoso displays of how to push the typographic grid. A new favorite.

1) Oase #75 and #76 — Oase is an excellent architecture and urban studies journal published by the Netherlands Architecture Institute and designed by Karel Martens of Werkplaats Typografie. Oase #75 is the 25th anniversary issue, and includes essays from Jurjen Zeinstra (“Houses of the Future”), René Boomkens (“Modernism, Catastrophe and the Public Realm”), and Frans Sturkenboom (“Come una ola de fuerza y luz: On Borromini’s Naturalism”), among many, many others. To be honest, there is so much interesting material in this issue that it’s hard to know where to start; look for this in specialty architecture bookstores and definitely consider picking up a copy. Meanwhile, Oase #76 arrived just in time for me to quote part of its interview with photographer Bas Princen in The BLDGBLOG Book – but the entire issue, bilingually printed in both English and Dutch and themed around what the editors call “ContextSpecificity,” is worth reading. There’s a whole section on “In-Between Buildings,” itself coming between long looks at context, tradition, and the generation of architectural form. #76 also includes virtuoso displays of how to push the typographic grid. A new favorite.

2) Blank Spots on the Map: The Dark Geography of the Pentagon’s Secret World by Trevor Paglen (Dutton) — Trevor Paglen is an “experimental geographer” at UC-Berkeley, well-known – perhaps infamous – for his successful efforts in tracking unmarked CIA rendition flights around the world. Using optical equipment normally associated with astronomy, Paglen has managed to photograph the goings-on of deep desert military bases and has even been able to follow US spy satellites through what he calls “the other night sky.” This book serves more or less as an introduction to Paglen’s work, from Afghanistan to Los Alamos.

3) The Thief at the End of the World: Rubber, Power, and the Seeds of Empire by Joe Jackson (Penguin) — Jackon’s book, new in paperback, explores the industrial implications of monopoly plantlife, telling the story of Henry Wickham, who “smuggled 70,000 rubber tree seeds out of the rainforests of Brazil and delivered them to Victorian England’s most prestigious scientists at Kew Gardens.” This led directly to the “great rubber boom of the early twentieth century,” we read – which itself resulted in such surreal sites as Henry Ford’s failed utopian-industrial instant city in the rain forest, Fordlandia. Here, Jackson describes that city, now in ruins and like something from a novel by Patrick McGrath:

The American Villa still stands on the hill. The green and white cottages line the shady lane, but the only residents now are fruit bats and trap-door tarantulas. The state-of-the-art hospital shipped from Michigan is deserted. Broken bottles and patient records litter the floor. A towering machine shop houses a 1940s-era ambulance, now on blocks. A riverside warehouse built to hold huge sheets of processed rubber holds six empty coffins arranged in a circle around the ashes of a small campfire.

Check out Jackson’s website for a bit more.

4) Ghettostadt: Łódź and the Making of a Nazi City by Gordon J. Horwitz (Harvard University Press) — By choosing the historical experience of Łódź, Poland, during its political assimilation and ethnic ghettoization by the Nazis, Gordon Horwitz shows how a long series of seemingly minor bureaucratic decisions can radically alter the normal urban order of things, paving the way for something as nightmarish as the Final Solution. This latter fact Horwitz memorably describes as “a phenomenon so unexpected and outrageous in design and execution as to exceed the then-understood limits of organized human cruelty.” About Łódź itself, he writes: “Secured by German arms, reshaped by German planning and technical expertise, the city was to be remade inside and out.” Horwitz shows how property confiscation, spatial rezoning, and literal new walls transformed Łódź into a Ghettostadt.

4) Ghettostadt: Łódź and the Making of a Nazi City by Gordon J. Horwitz (Harvard University Press) — By choosing the historical experience of Łódź, Poland, during its political assimilation and ethnic ghettoization by the Nazis, Gordon Horwitz shows how a long series of seemingly minor bureaucratic decisions can radically alter the normal urban order of things, paving the way for something as nightmarish as the Final Solution. This latter fact Horwitz memorably describes as “a phenomenon so unexpected and outrageous in design and execution as to exceed the then-understood limits of organized human cruelty.” About Łódź itself, he writes: “Secured by German arms, reshaped by German planning and technical expertise, the city was to be remade inside and out.” Horwitz shows how property confiscation, spatial rezoning, and literal new walls transformed Łódź into a Ghettostadt.

5) Condemned Building by Douglas Darden (Princeton Architectural Press) — The late Douglas Darden’s work seems both underknown and underexposed (perhaps because so little of it can be found online). This book, published in 1993, collects ten speculative projects, including the Museum of Impostors, the Clinic for Sleep Disorders, and the Oxygen House, complete with plans, models, elevations, and historical engravings. Darden’s work is an interesting hybrid of narrative fiction, visual storytelling, and architectural design – and so naturally of great interest to BLDGBLOG. For instance, his “Temple Forgetful” project weds amnesia, flooding, and the mythic origins of Rome. Good stuff.

6) Architecture Depends by Jeremy Till (MIT Press) — Architectural theory written with the rhetorical pitch of a blog, Architecture Depends is a kind of from-the-hip philosophy of “rogue objects,” construction waste, massive landfills, “lo-fi architecture,” and the fate of buildings over long periods of time. As Till states in the book’s preface, “Mess is the law.”

7) Wired for War: The Robotics Revolution and Conflict in the Twenty-first Century by P.W. Singer (Penguin) — An extremely provocative look at the future of war in an age of robot swarms and autonomous weaponry, Singer’s book is nonetheless a bit too casual for its own good (reading that Singer wrote the book because robots are “frakin’ cool” doesn’t help me trust the author’s sense of self-editing). Having said that, there is so much here to discuss and explore further that it’s impossible not to recommend the book – eyepopping micro-histories of individual war machines come together with Singer’s on-the-scene anthropological visits to robotics labs and military testing grounds, by way of Artificially Intelligent snipers, drone “motherships” forming militarized constellations in the sky, and even “mud batteries” and automated undersea warfare. Like Singer’s earlier Corporate Warriors – another book I would quite strongly recommend – the often terrifying implications of Wired for War nag at you long after you’ve stopped reading. For what it’s worth, by the way, this book seems almost perfectly timed for the release of Terminator Salvation.

8) Sand: The Never-Ending Story by Michael Welland (University of California Press) — This book is awesome, and I hope to draw a much longer post out of it soon. Only slightly marred by an unfortunate subtitle, Welland’s book is disproportionately fascinating, considering its subject matter. On the other hand, “it has been estimated,” he writes, “that on the order of a billion sand grains are born around the world every second” (emphasis his) – so the sheer ubiquity of his referent makes the book worth reading. From the early history of sand studies to the aerial physics of dunes – by way of the United States’ little-known WWII-era Military Geology Unit – the interesting details of this book are inexhaustible.

8) Sand: The Never-Ending Story by Michael Welland (University of California Press) — This book is awesome, and I hope to draw a much longer post out of it soon. Only slightly marred by an unfortunate subtitle, Welland’s book is disproportionately fascinating, considering its subject matter. On the other hand, “it has been estimated,” he writes, “that on the order of a billion sand grains are born around the world every second” (emphasis his) – so the sheer ubiquity of his referent makes the book worth reading. From the early history of sand studies to the aerial physics of dunes – by way of the United States’ little-known WWII-era Military Geology Unit – the interesting details of this book are inexhaustible.

9) A Passion for Nature: The Life of John Muir by Donald Worster (Oxford University Press) — Donald Worster has written a long biography of John Muir, the naturalist and writer who once famously climbed as high as he could into the canopy of a Californian forest during a lightning storm so that he could see what it was like to experience nature firsthand. At its most basic, Worster’s book explores the natural landscape of the American West as “a source of liberation.”

Going into wild country freed one from the repressive hand of authority. Social deferences faded in wild places. Economic rank ceased to matter so much. Bags of money were not needed for survival – only one’s wits and knowledge. Nature offered a home to the political maverick, the rebellious child, the outlaw or runaway slave, the soldier who refused to fight, and, by the late nineteenth century, the woman who climbed mountains to show her strength and independence.

Worster himself is an environmental historian at the University of Kansas.

10) Le Corbusier: A Life by Nicholas Fox Weber (Alfred A. Knopf) — I’m strangely excited to read this, actually – and I say “strangely” because I am not otherwise known for my interest in reading about Le Corbusier. But Nicholas Fox Weber’s approximately 765 pages of biographical reflection on Corbu’s life look both narratively satisfying, as a glimpse into the man’s daily ins and outs over eight decades, but also architecturally minded, contextualizing Le Corbusier’s spatial work within his other political (and libidinal) interests. I hope to dive into this one over the summer.

* * *

All

Books Received:

August 2015,

September 2013,

December 2012,

June 2012,

December 2010 (“Climate Futures List”),

May 2010,

May 2009, and

March 2009.

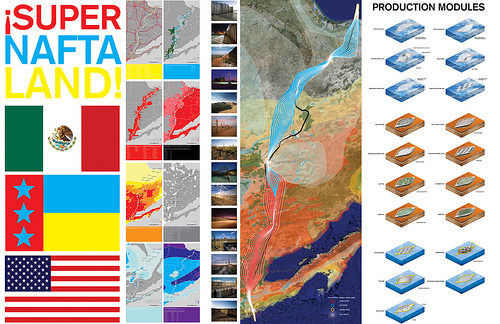

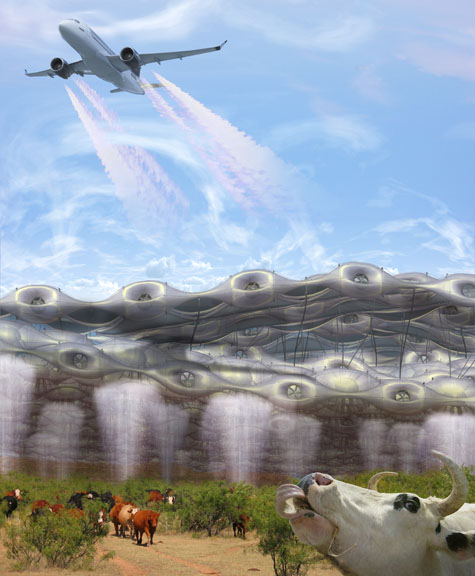

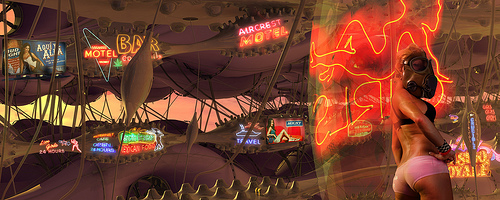

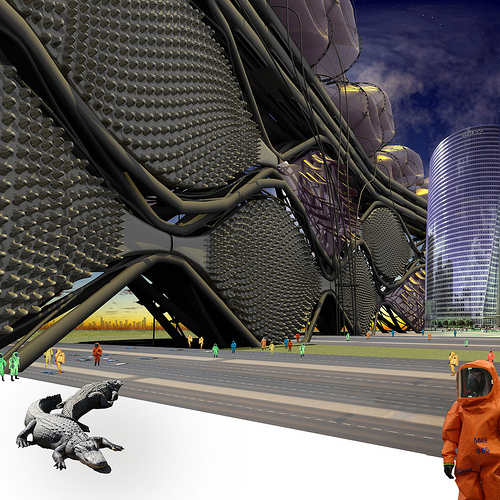

[Image: From ¡Super NAFTA Land! by Richie Gelles].

[Image: From ¡Super NAFTA Land! by Richie Gelles].

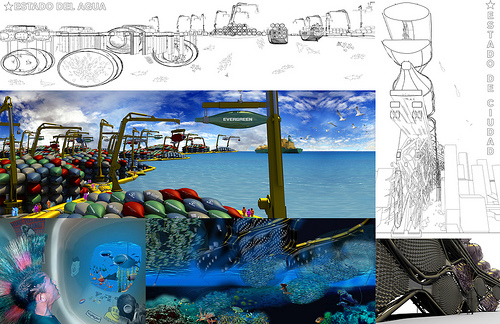

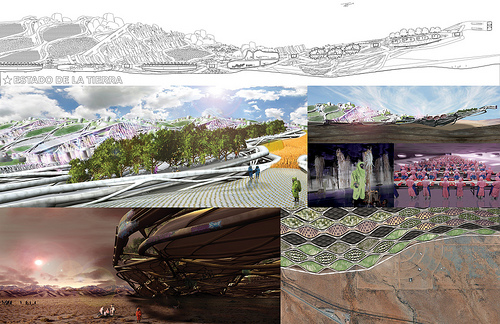

[Images: From ¡Super NAFTA Land! by Richie Gelles; be sure to view the sections much larger: Estado de la Tierra and Estado del Aire].

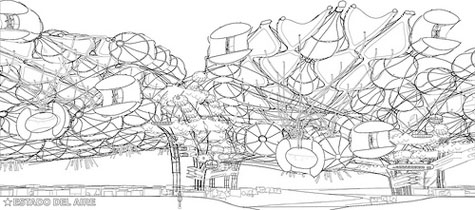

[Images: From ¡Super NAFTA Land! by Richie Gelles; be sure to view the sections much larger: Estado de la Tierra and Estado del Aire]. [Image: From ¡Super NAFTA Land! by Richie Gelles].

[Image: From ¡Super NAFTA Land! by Richie Gelles]. [Image: From the amazing Superheroes series by photographer

[Image: From the amazing Superheroes series by photographer  [Image: Bookstore for Shibuya Publishing, Japan, designed by

[Image: Bookstore for Shibuya Publishing, Japan, designed by  1)

1)  4)

4)  8)

8)  [Image: Logo by

[Image: Logo by  [Image: So good you can’t see it: a hunter wearing a

[Image: So good you can’t see it: a hunter wearing a

[Images: Two more examples of

[Images: Two more examples of  [Image: This suit apparently only weights 2.25 lbs. Photo courtesy of

[Image: This suit apparently only weights 2.25 lbs. Photo courtesy of  [Image: From

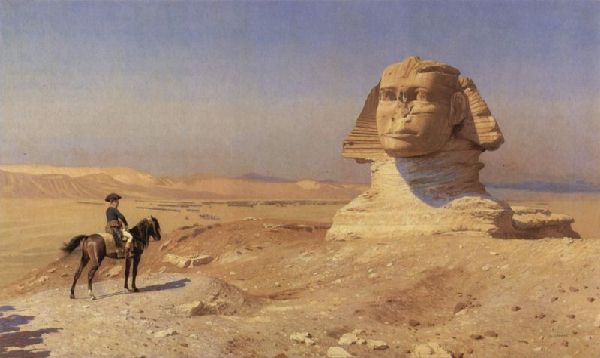

[Image: From  [Image: Napoleon in Egypt].

[Image: Napoleon in Egypt]. [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image:

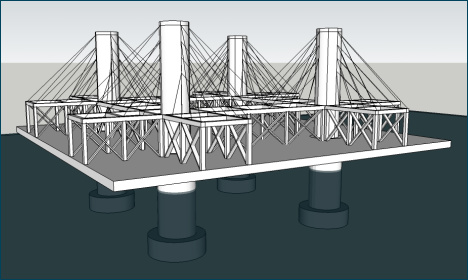

[Image:  [Image: The basic platform; design your seastead atop this and

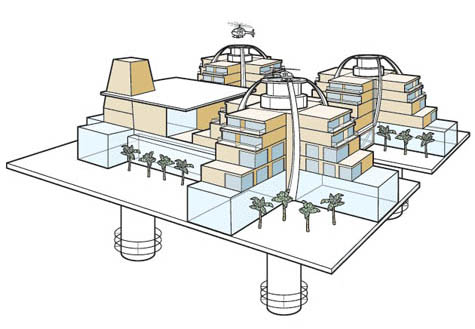

[Image: The basic platform; design your seastead atop this and  [Image: The sample design].

[Image: The sample design]. [Image: An illustrated variation of the sample design, from

[Image: An illustrated variation of the sample design, from