[Images: (left) An archaeologist examines soil cores. (right) Researchers plot lost roads across the grounds of Monticello. Courtesy of the Glenn A. Black Laboratory of Archaeology at IU Bloomington].

[Images: (left) An archaeologist examines soil cores. (right) Researchers plot lost roads across the grounds of Monticello. Courtesy of the Glenn A. Black Laboratory of Archaeology at IU Bloomington].

It’s hard to resist a caption referring to a “team of researchers” who have used their “electrical resistivity profiler to discover long-buried roads around the historic Virginia home” of 18th century U.S. president Thomas Jefferson. But that’s exactly what you’ll see courtesy of a recent press release from Indiana University.

Specifically, we read, a team of Indiana University archaeologists have “conducted a landscape study to find evidence of two lost roads: a ‘kitchen road’ that serviced the Monticello kitchen, and a formal carriageway that circled along the Ellipse Fence marking the edge of the East Lawn and the formal landscape in front of Monticello.”

A combination of soil cores and direct electrical data helped that team outline this otherwise lost geography at the heart of U.S. presidential history and across the original lawns of American Palladianism. Jefferson, as you might know, was an architect, one heavily influenced by the texts and buildings of Andrea Palladio. American architecture, from day one, was, in a sense, a facsimile: created, with far-reaching variations and personal stylistic quirks, based on reproduced manuscripts from Europe.

In any case, stepping back: beneath Jefferson’s lawn are lost roads.

I’m reminded here of an amazing story published two years ago in the New York Times about “ancient roads,” dating from colonial times, in the U.S. state of Vermont.

[Image: Walking an “ancient road” in Vermont; photo by Joseph Sywenkyj for The New York Times].

[Image: Walking an “ancient road” in Vermont; photo by Joseph Sywenkyj for The New York Times].

As the The New York Times explained back then, a 2006 state law gave Vermont residents a strong incentive to uncover the buried throughways in, around, and through their often quite rural towns. Indeed, “citizen volunteers are poring over record books with a common, increasingly urgent purpose: finding evidence of every road ever legally created in their towns, including many that are now impassable and all but unobservable.”

These “elusive roads”—many of them “now all but unrecognizable as byways”—are lost routes, connecting equally erased destinations. In almost all particular cases, they have barely even left a trace on the ground; their presence is almost entirely textual.

They are not just lost roads; they are road that have been deterrestrialized.

If these ancient routes can be re-discovered, however, then Vermont state law dictates that they can also be added to official town lands (and thus be eligible for some kind of federal something-or-other). Accordingly:

Some towns, content to abandon the overgrown roads that crisscross their valleys and hills, are forgoing the project. But many more have recruited teams to comb through old documents, make lists of whatever roads they find evidence of, plot them on maps and set out to locate them.

And, in what is surely one of the most interesting geographical subplots in recent newspaper publishing, we read: “Even for history buffs, the challenge is steep: evidence of ancient roads may be scattered through antique record books, incomplete or hard to make sense of.”

Like something out of the poetry of Paul Metcalf, or even William Carlos Williams, the descriptions found in these old documents are narrative, impressionistic, and vague. They “might be, ‘Starting at Abel Turner’s front door and going to so-and-so’s sawmill,’ said Aaron Worthley, a member of the ancient roads committee in Huntington, southeast of Burlington. ‘But the house might have burned down 100 years ago. And even if not, is the front door still where it was in 1815? These are the kinds of questions we’re dealing with.'”

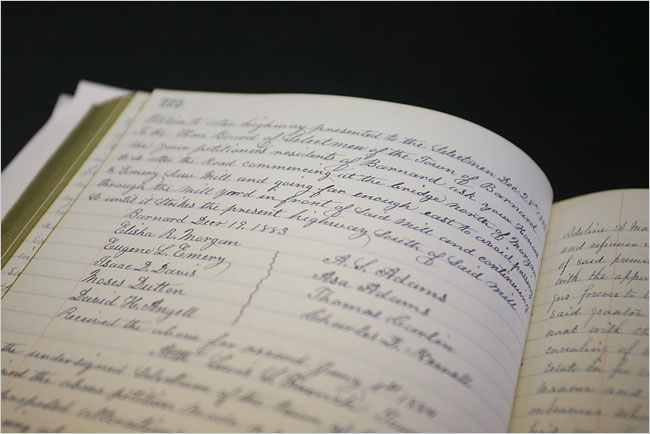

[Image: A hand-written inventory of Vermont’s ancient routes; photo by Joseph Sywenkyj for The New York Times].

[Image: A hand-written inventory of Vermont’s ancient routes; photo by Joseph Sywenkyj for The New York Times].

While making sense of cryptic references to lost byways is fascinating in and of itself, these acts of perambulatory interpretation are part of a much larger, fairly mundane attempt to end “fights between towns and landowners whose property abuts or even intersects ancient roads.”

In the most infamous legal battle, the town of Chittenden blocked a couple from adding on to their house, saying the addition would encroach on an ancient road laid out in 1793. Town officials forced a showdown when they arrived on the property with chain saws one day in 2004, intending to cut down trees and bushes on the road until the police intervened.

The article here goes on to refer to one local, a lawyer, who explains that “he loved getting out and looking for hints of ancient roads: parallel stone walls or rows of old-growth trees about 50 feet apart. Old culverts are clues, too, as are cellar holes that suggest people lived there; if so, a road probably passed nearby.”

Think of it as landscape hermeneutics: hunting down traces of a disappeared landscape.

What would happen, then, if you discovered that an ancient road actually passes through your house? Your living room is a former throughway, and old paths knot and twirl off to every side; one even leads right through the guest bedroom. And then another road pops up, and another—and you realize that you live on the intersecting scars of a lost built environment, some old village that disappeared or was destroyed in an H.P. Lovecraft-like enigmatic disaster.

[Image: An old Roman road in Britain; photo via Historic UK].

[Image: An old Roman road in Britain; photo via Historic UK].

I’d also be curious, meanwhile, to see what might happen if such a law was passed in a city like London. In an old but interesting review of the book London: City of Disappearances, edited by Iain Sinclair, we’re told that London “is a city of the forgotten.” It is where anyone “can still disappear without trace.” Indeed, London is a city “built upon lost things”; it “towers above forgotten underground rivers and discarded tunnels. It is built upon old graveyards and burial pits.”

Best of all, entire London streets have disappeared: “Catherine Street, Jewin Street, Golden Place are just three of the vanished thoroughfares named in a litany of sorrowful mysteries,” our reviewer points out. “Other streets have been curtailed. Swallow Street has been swallowed by burgeoning London. Grub Street has been renamed Milton Street.”

So what would happen if someone—who liked “getting out and looking for hints of ancient roads”—were to set about such a task elsewhere, in a city made from unstable geographies flashing in and out of county land registers?

I’m reminded here of China Miéville’s short story “Reports of Certain Events in London,” in which “unstable” streets appear and disappear throughout the city. One night they’re there, the next night they’re not.

Or take Chris Carlsson’s explorations of San Francisco’s ghost streets. “Intrepid explorers of San Francisco regularly stumble upon the many ghost streets that still hide all over town, rewarding the patient pedestrian for their diligence,” Carlsson wrote last autumn. “Mostly they are on hillsides where steep grades impeded road building at earlier moments in history, but they’re still presented as if they were through-streets on the maps.”

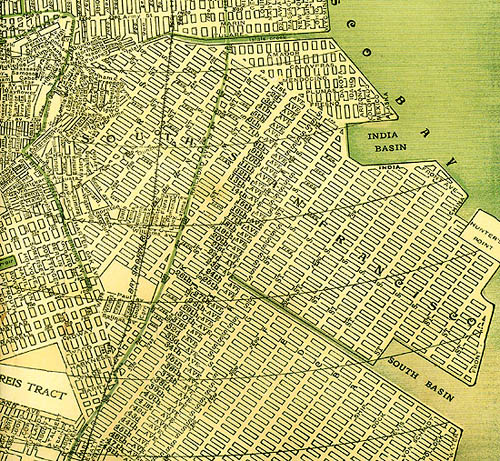

[Image: A map of San Francisco, including many “ghost streets,” courtesy of Streetsblog SF].

[Image: A map of San Francisco, including many “ghost streets,” courtesy of Streetsblog SF].

Carlsson’s post—something every San Franciscan should read—seemingly paved the way for a later exploration of “San Francisco’s unaccepted streets,” throughways too ephemeral for any real act of archaeology.

This unaccepted geographical unconscious of the city was recently mapped by Nicholas de Monchaux in an awesomely ambitious project called Local Code. It’s hard to exaggerate how interesting this project is; the following embedded video barely does it justice:

Here we are, then, surrounded by lost roads, forgotten throughways, and unaccepted streets. We turn on ground-penetrating radar and we find lost highways. What new cartographies could possibly account for these layers? With avenues leading nowhere and medieval freeways whose stratigraphic routes remain unpaved?

Finally—though by no means answering these questions—roughly two years ago, historian Kitty Hauser published a book called Bloody Old Britain. That book told the story of pilot, and accidental archaeologist, O.G.S. Crawford. Crawford pioneered the use of aerial photography in both discovering and analyzing ancient sites. Learning to read the landscape from the air, on the look-out for German ditches and bunkers, Crawford “would later apply this kind of skill honed in war, the trained interpretation of visual evidence, to the peacetime work of archaeology,” Hauser writes.

In the process, he realized almost instantly that you could detect, from high above, the traces of ancient landscape features that would otherwise have gone unseen. For instance, “at certain times of day, when the sun is low in the sky, the outlines of ancient fields become visible over Salisbury Plain, as shadows throw their ridges and dimples into sharp relief; these are known as ‘shadow sites.’” Much of this comes down to the specific species of plant growing over these landscapes:

Field archaeologists know that vegetation grows differently on soil that has been disturbed, even if that disturbance happened centuries ago. They know that crops grow more luxuriantly over silted-up ditches, and more stunted where there are buried remains. The site of a Roman villa might go unnoticed until a field of wheat grows and ripens, to reveal most strangely the outlines of buried masonry, only to disappear again at harvest. Slight contours or indentations on the land marking out the site of a lost settlement might be invisible to the eye until a low sun throws them into sharp but momentary relief.

Further:

Barley is a more sensitive ‘developer,’ for example, than oats, wheat, or grass, but only in certain soils. Dry spells can bring about remarkably sharp crop sites, like the outline of the medieval tithe barn, complete with buttresses, that appeared in the grass at Dorchester in June of 1938.

Hauser continues, pushing the awe factor:

One of the most remarkable things about aerial archaeology is that very few human processes will completely remove a site from view for ever. It might be decades—centuries even—before the right combination of crop growth, rain, sun, and aerial observer results in a site manifesting itself and being photographed. But unless deep excavations or quarrying are carried out, removing all traces of the site, the possibility remains that one day, under new conditions, it will reveal itself.

And, thus, “Photographs of unimpressive-looking mounds and lumps, the sort of thing one might not notice as one went past in a car or a train, turn out to be burial mounds, still for all we know containing crouching skeletons or buried treasure. You just needed to know where to look.” And Crawford knew where to look: there were ancient archaeological features everywhere, from buried roads to wooden menhirs rotting back into the soil. Britain was very old, Crawford himself could see; it was Bloody Old Britain.

[Image: O.G.S. Crawford and his archaeological airplane; via Kitty Hauser’s Bloody Old Britain].

[Image: O.G.S. Crawford and his archaeological airplane; via Kitty Hauser’s Bloody Old Britain].

What, then, if we could combine all this? Dead streets buried beneath the sprawling lawn of a U.S. president—himself now erased from the historical memory of U.S. Conservatives—crossed with lost streets from San Francisco, wed with linear archaeological sites known only from the air of 1910s England, meeting ancient roads through the hills of rural Vermont, informing short story sci-fi by China Miéville: how does our understanding of the built environment accordingly change?

What ancient routes exist all around us—like the dead streets of California City?

[Image: California City, CA; view much larger!].

[Image: California City, CA; view much larger!].

When I first mentioned the story of Vermont’s ancient roads two years ago on BLDGBLOG, commenters pointed out things like the Icknield Way, a.k.a. the “oldest road in Britain,” as well as lost railway lines in North Dakota:

I’ve done a lot of ‘landscape hermeneutics’ with former rail lines. I’m working on photographing every town in North Dakota, and most of these towns were built on a rail line. Many of those lines are now long-gone, so there’s often a ridge running through the town where the railroad used to be. Some of the tiniest spots (like Petrel) that still manage to get on the map can only be identified by a swath of cleared land where a railroad siding and depot might have been.

Or, from Ian Milliss, perhaps the best commenter in BLDGBLOG history (punctuation added):

For the last two years I’ve been on a National Trust committee working on heritage listing for Coxs Road, the first road across the Blue Mountains west of Sydney that opened up Australia to European settlement. Its bicentenary is in 2015.

[Image: Three views of Australia’s lost Coxs Road, taken in the Woodford area].

[Image: Three views of Australia’s lost Coxs Road, taken in the Woodford area].

Numerous pieces of it survive intact, and it does, indeed, sometimes disappear under houses. I’ve also been working on an overlay of it for Google Earth and even some virtual sections done using SketchUp… Its entire construction is detailed in the diaries and reports of its builders so that it can still be tracked through farmland where there is no visible trace of it.

It also relates to Australian indigenous mapping via ancestor stories and songlines, to produce virtual highways that can easily be followed but have very little obvious physical evidence of their existence.

Geography is a dream. Like an absorbed twin, we are surrounded by forgotten roads. That there are lost routes even at the spatial core of the U.S. presidency is just one of many surprising acts of poetry that this world seems always capable of.

(Monticello story spotted via Jessica Saraceni’s great newsfeed over at Archaeology Magazine. Of interest, meanwhile, earlier on BLDGBLOG: Ancient Roads, from which part of this post actually comes, Ancient Lights, and Z).

[Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: Photo by Kevin Sellers, courtesy of the

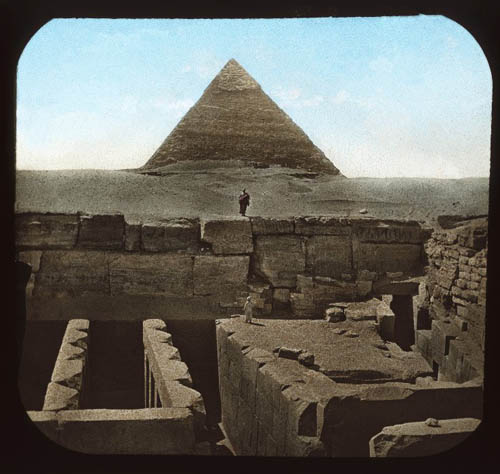

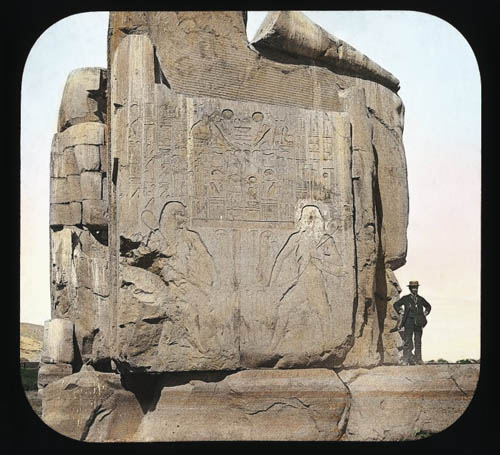

[Image: Photo by Kevin Sellers, courtesy of the  [Image: A pyramid at Giza, the earth archaeo-surgically opened at its base; courtesy of the

[Image: A pyramid at Giza, the earth archaeo-surgically opened at its base; courtesy of the  [Image: Giza, courtesy of the

[Image: Giza, courtesy of the

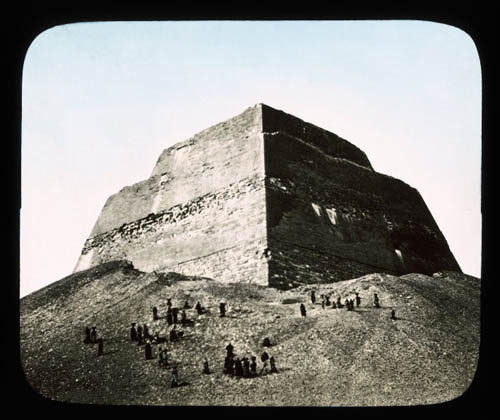

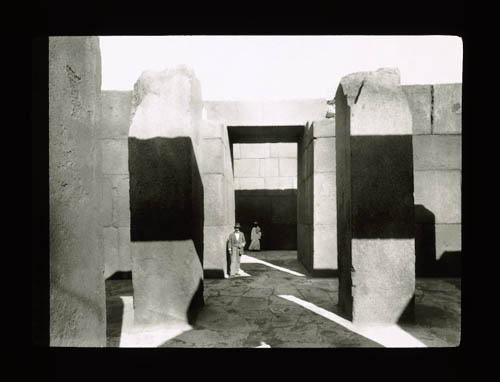

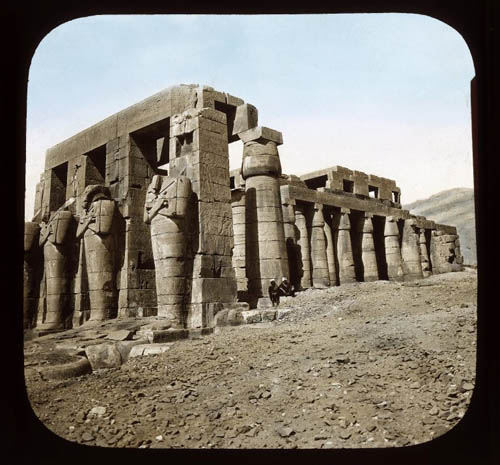

[Images: Brutalism at Giza, circa 2,500 B.C.; courtesy of the

[Images: Brutalism at Giza, circa 2,500 B.C.; courtesy of the

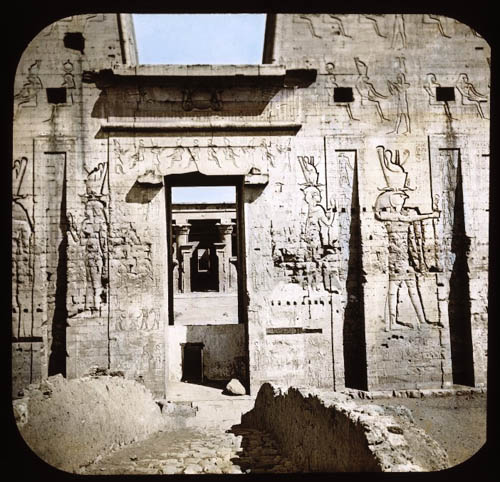

[Image: Ruins in light, courtesy of the

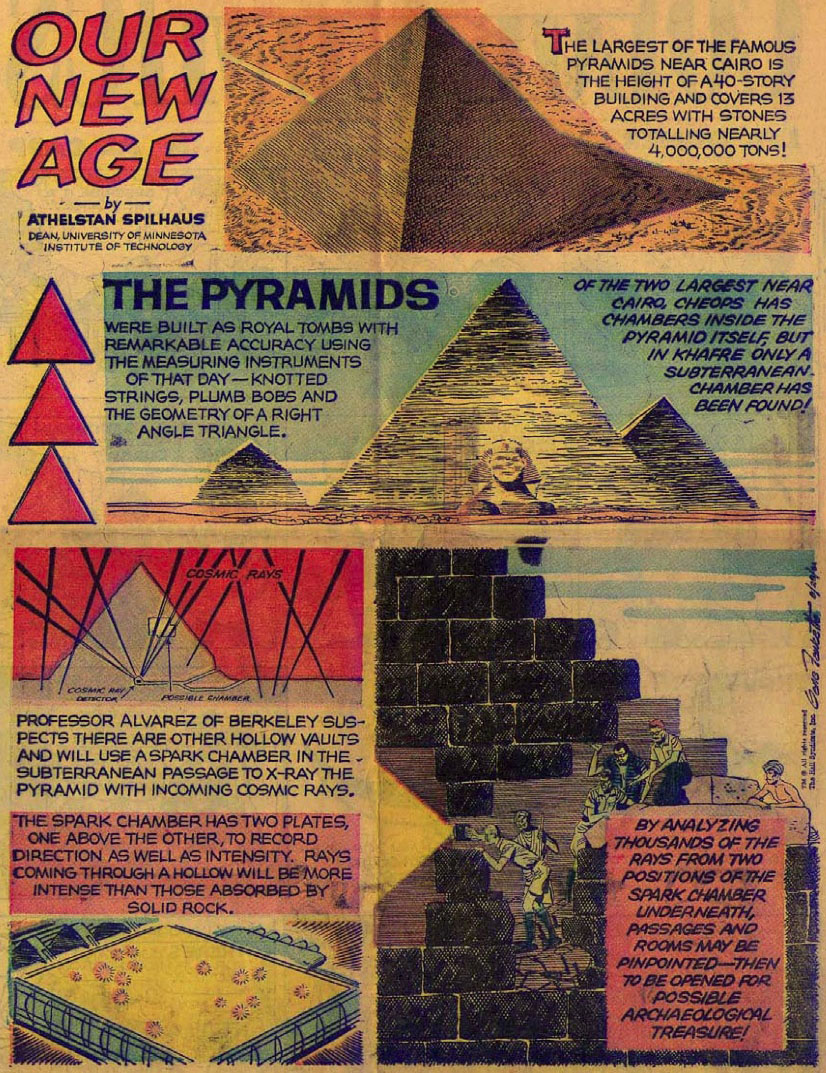

[Image: Ruins in light, courtesy of the  [Image: An illustrated depiction of the physicists’ sub-pyramidal adventures; view

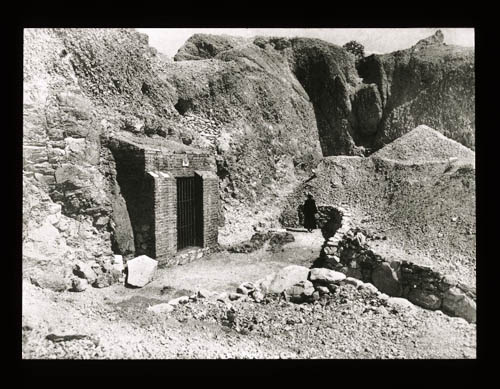

[Image: An illustrated depiction of the physicists’ sub-pyramidal adventures; view  [Image: Tombs at Abu Simbel, Egypt, courtesy of the

[Image: Tombs at Abu Simbel, Egypt, courtesy of the  [Image: The hollow hills of Egypt’s

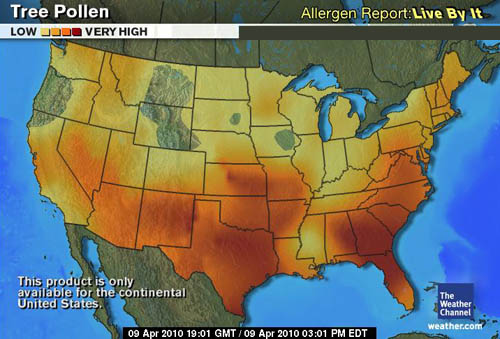

[Image: The hollow hills of Egypt’s  [Image: Tree pollen map, brought to you by the

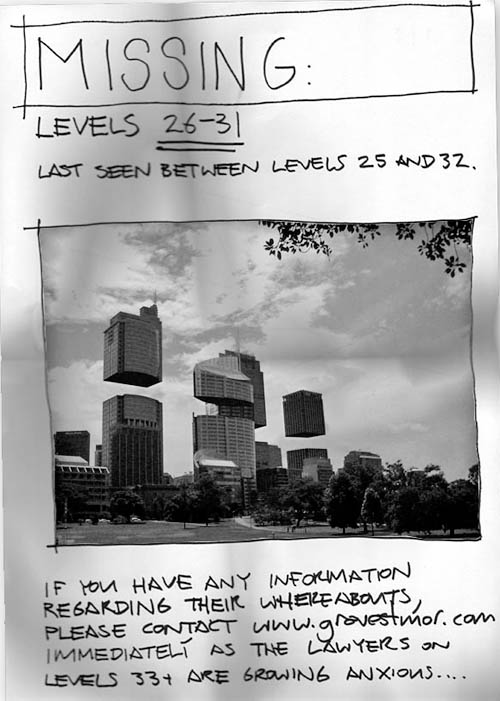

[Image: Tree pollen map, brought to you by the  [Image: Proposal for a new

[Image: Proposal for a new  [Image: Super Colossal’s competition-winning design for

[Image: Super Colossal’s competition-winning design for  [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: Via

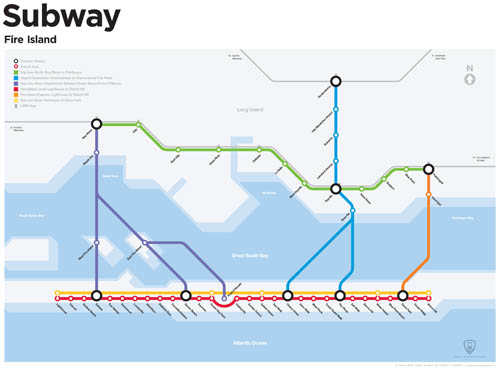

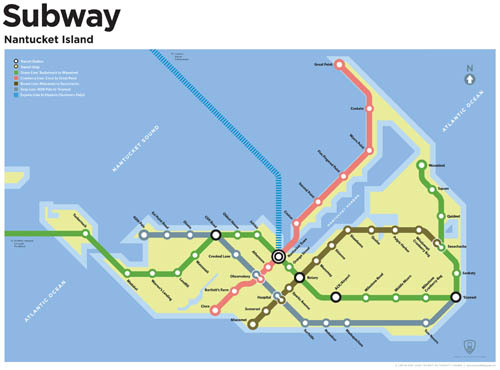

[Image: Via  [Image: A speculative future subway map by

[Image: A speculative future subway map by

[Images: Maps by

[Images: Maps by  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: The

[Image: The

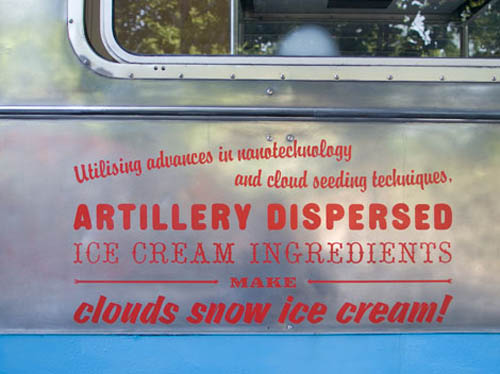

[Images: From the

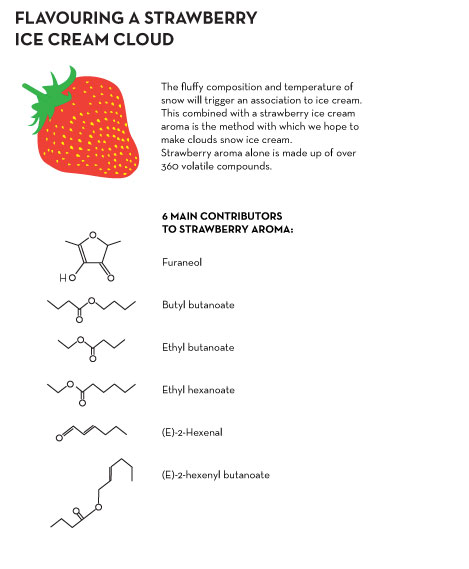

[Images: From the  [Image: A how-to guide for precipitating strawberry ice cream by Zoe Papadopoulou and Cathrine Kramer].

[Image: A how-to guide for precipitating strawberry ice cream by Zoe Papadopoulou and Cathrine Kramer]. [Image: From a previous

[Image: From a previous  [Image: From a previous

[Image: From a previous  [Images: Photos from previous

[Images: Photos from previous  [Image: From a previous

[Image: From a previous  [Image: O.T. (2006) by

[Image: O.T. (2006) by  [Image: Abstract thought is a warm puppy (2008) by

[Image: Abstract thought is a warm puppy (2008) by  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images:

[Images: