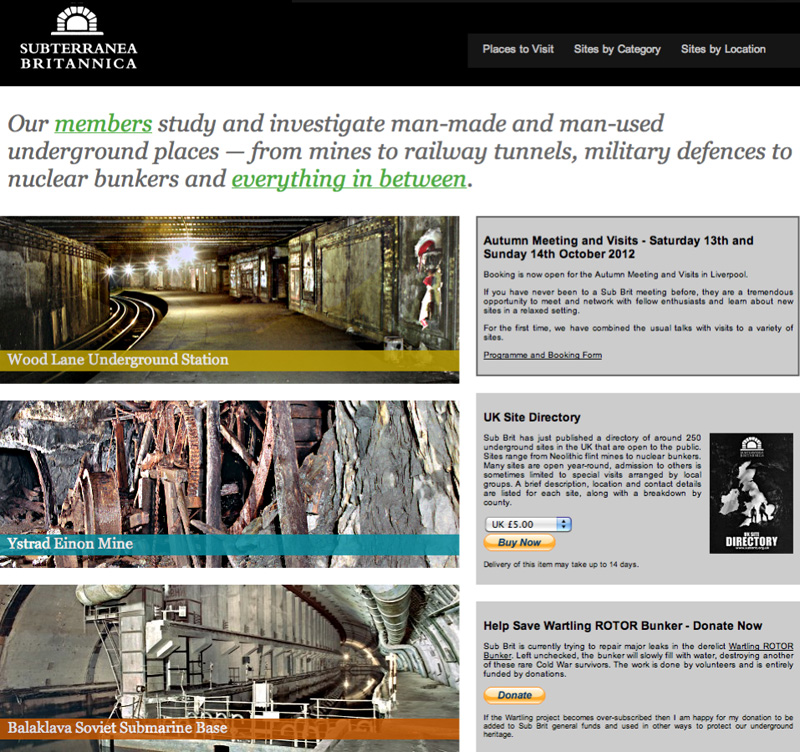

I finally became a paying member of Subterranea Britannica this week, a website and historical organization whose interests (and influence) cast a long shadow over this blog’s early years.

I finally became a paying member of Subterranea Britannica this week, a website and historical organization whose interests (and influence) cast a long shadow over this blog’s early years.

Joining is £28 a year for overseas members and seems well worth it so far, having received my first issue of their internal newsletter, Subterranea, just last night. From Irish souterrains—described as “the ‘underground castles’ of early medieval Ireland, used as strongholds and escape tunnels,” or, in the words of Current Archaeology, “secret tunnels dug to outwit marauding Norsemen”—to World War I tunnels in La Boisselle, France, and from plans for future deep-level “supersewers” beneath both Milwaukee and London to, amongst many other fascinating things, a project I can’t wait to learn more about called the London Power Tunnels, a mafia boss who was captured in an “underground hideout” built twelve miles outside Naples (“access from within the house was via a sliding door on rails in one of the bedrooms,” Subterranea explains), the fact that Northern Ireland had “secret contingency plans” for surviving a nuclear war and they involved stockpiling “more than 100,000 pieces of plastic cutlery,” to the enormous “stacks of gold bars worth £156 billion stored in an old canteen deep below the streets” of London in a former WWII air-raid shelter now used by the Bank of England, there is a mind-boggling amount of interesting things to read.

Even better, membership comes with otherwise unobtainable invitations to events and underground site tours throughout the UK. Consider joining, if this sort of stuff piques your interest.

Category: BLDGBLOG

Secret Soviet Cities

[Images: From ZATO: Secret Soviet Cities during the Cold War at Columbia’s Harriman Institute; right three photographs by Richard Pare].

[Images: From ZATO: Secret Soviet Cities during the Cold War at Columbia’s Harriman Institute; right three photographs by Richard Pare].

Speaking of Van Alen Books: earlier this week, they hosted a panel on the topic of “Secret Soviet Cities During the Cold War.” These were closed cities or ZATO, “sites of highly secretive military and scientific research and production in the Soviet Empire. Nameless and not shown on maps, these remote urban environments followed a unique architectural program inspired by ideal cities and the ideology of the Party.”

The ZATO, we read courtesy of an interesting post on the Russian History Blog, was a “Closed Administrative-Territorial Formation (Zakrytoe administrativno-territorial’noe obrazovanie, ZATO)”:

[T]he cities themselves were never shown on official maps produced by the Soviet regime. Implicated in the Cold War posture of producing weapons for the Soviet military-industrial complex, these cities were some of the most deeply secret and omitted places in Soviet geography. Those who worked in these places had special passes to live and leave, and were themselves occluded from public view. Most of the scientists and engineers who worked in the ZATOs were not allowed to reveal their place or purpose of employment.

In any case, there are two main reasons to post this:

[Image: Photo by I. Yakovlev/Itar-Tass, courtesy of Nature].

[Image: Photo by I. Yakovlev/Itar-Tass, courtesy of Nature].

1) Just last week, Nature looked at Soviet-era experiments in these closed cities, where “nearly 250,000 animals were systematically irradiated” as part of a larger medical effort “to understand how radiation damages tissues and causes diseases such as cancer.”

In an article that is otherwise more medical than it is urban or architectural, we nonetheless read of a mission to the formerly closed city of Ozersk in order to rescue this medical evidence from the urban ruins: “After a long flight, a three-hour drive and a lengthy security clearance, a small group of ageing scientists led the delegation to an abandoned house with a gaping roof and broken windows. Glass slides and laboratory notebooks lay strewn on the floors of some offices. But other, heated rooms held wooden cases stacked with slides and wax blocks in plastic bags.” These slides and wax blocks “provide a resource that could not be recreated today,” Nature suggests, “for both funding and ethical reasons.”

Perhaps it goes without saying, but the idea of medical researchers helicoptering into the ruins of a formerly secret city in order to locate medical samples of fatally irradiated mutant animals is a pretty incredible premise for a future film.

[Images: (top) photo by Tatjana Paunesku; (bottom) photo by S. Tapio. Courtesy of Nature].

[Images: (top) photo by Tatjana Paunesku; (bottom) photo by S. Tapio. Courtesy of Nature].

2) More relevant for this blog, you only have five days left to see the exhibition ZATO: Secret Soviet Cities during the Cold War up at Columbia University’s Harriman Institute, featuring “ZATO archival materials, camouflage maps of strategic sites, secret diagrams of changing ZATO names/numbers, [and] ZATO passports.”

That exhibition documents everything from the “special food and consumer supplements given as rewards for the secrecy and ‘otherness’ of the sites,” to the cities’ eerily suburbanized, half-abandoned state today: “Today there are 43 ZATO on the territory of the Russian Federation. Their future is uncertain: some may survive; others may disappear as urban formations within the context of Russian suburbs.” Check it out if you get a chance.

More info at the Harriman Institute.

Papercraft

[Image: Wifi-blocking wallpaper from the Grenoble Institute of Technology].

[Image: Wifi-blocking wallpaper from the Grenoble Institute of Technology].

1) A collaboration between the Grenoble Institute of Technology and the Centre Technique du Papier has produced wifi-blocking wallpaper: a printable electromagnetic shield that “only blocks a select set of frequencies used by wireless LANs, and allows cellular phones and other radio waves through.”

As The Verge explains, the wallpaper uses “conductive ink containing silver crystals” printed in an otherwise innocuous abstract snowflake pattern. In other words, only if you know exactly what to look for—or in a strange moment of speculative paranoia—would you realize that the paper on the walls around you is actually an electronic device.

Competitively priced with standard wallpapers, it might soon be decking and protecting the walls in a house or office near you.

[Image: Printed electronics produce 2D loudspeakers; photo by Hendrik Schmidt, via Printed Electronics World].

[Image: Printed electronics produce 2D loudspeakers; photo by Hendrik Schmidt, via Printed Electronics World].

2) 2D printable loudspeakers have become a reality. Fully functioning speakers can now be “printed with flexography on standard paper” using “several layers of a conductive organic polymer and a piezoactive layer.”

Like something out of The Ticket That Exploded, we read that “paper loudspeakers could, for instance, be integrated into common print products. As such, they offer an enormous potential for the advertising segment.” In other words, books, newspapers, and magazines could soon literally be yelling at you to buy more products. Less cynically, though, this also raises the fairly fascinating possibility that we could someday release songs inside pamphlets, audiobooks inside the very hardcovers they narrate, field recordings inside road maps, or even add strips of ambient acoustics to rooms through loudspeaker wallpaper.

After all, sound wallpapers are, incredibly, also possible, resulting in large-scale, acoustically active surfaces, from objects to interior walls. The rave of the future will be one person with a roll of paper, pasting up sounds till sunrise.

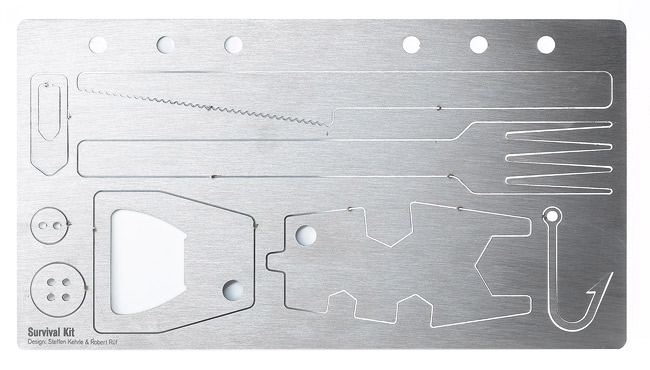

[Images: Lasercut survival kits by Steffen Kehrle].

[Images: Lasercut survival kits by Steffen Kehrle].

3) However, if wifi-blocking wallpaper and printable 2D loudspeakers aren’t your cup of tea, then you can also laser-cut any reasonably stiff 2D surface into an urban survival kit.

Designer Steffen Kehrle‘s work implies that, with the right laser patterns and a thin sheet of cardstock—even wood veneer—the keys to the city could be yours. Done right, this same approach could offer more than just tactical culinary devices, as seen above, but small-scale urban equipment: pop-out objects for navigating the built environment around you.

Mega City Soundtrack

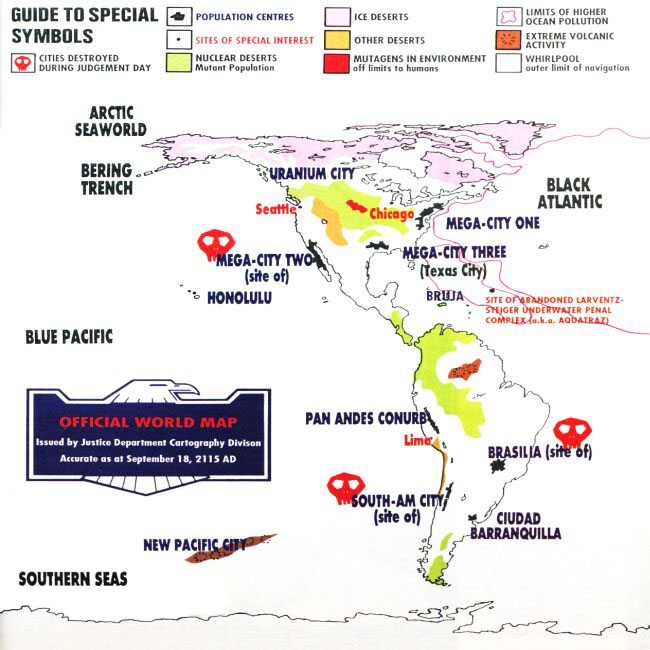

[Image: A map of fictional mega cities, via 2000AD].

[Image: A map of fictional mega cities, via 2000AD].

A short review in the most recent Wire discusses a new album by Geoff Barrow and Ben Salisbury: a speculative urban soundtrack to Mega City One, a “post-apocalyptic sprawl covering the eastern seaboard of the United States” from Judge Dredd. “Portishead’s Geoff Barrow and BBC soundtrack composer Ben Salisbury’s instrumental interpretation” of the city, The Wire writes, “evoke[s] the gunmetal grey of life in Mega City One, its multilevel labyrinth of self-contained blocks, zipstrips and boomways reflecting darkly in the album’s tarnished metallic textures and gridlike structures.”

The retro-Alan Howarthian synthesizers, a “rigorously imagined sound map” of the city, can be streamed in full via Bandcamp.

For those of you in London, meanwhile, Barrow and Salisbury will perform excerpts from the “weirdly addictive“—or is it “hackneyed“?—album at Orbital Comics on 16 May.

Water vs. World

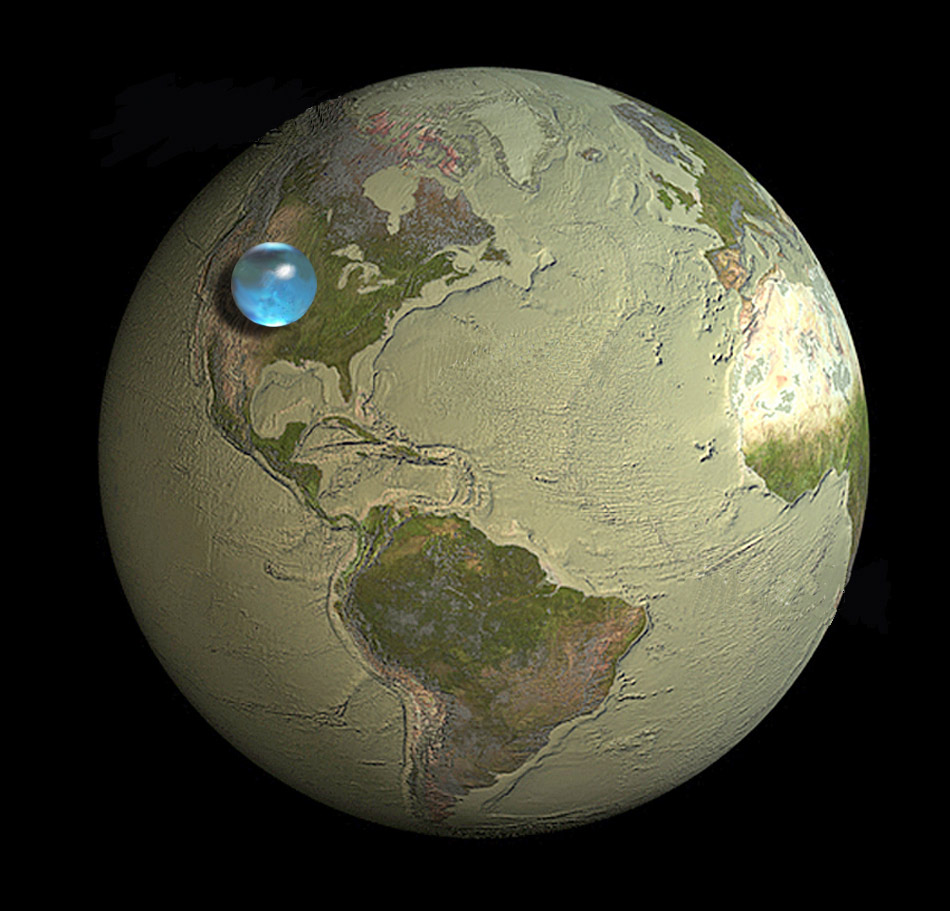

[Image: Illustration by Jack Cook, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution; courtesy of the USGS].

[Image: Illustration by Jack Cook, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution; courtesy of the USGS].

In Charles Fishman’s compelling exploration of water on Earth, The Big Thirst, there is a shocking statement that, despite the apparent inexhaustibility of the oceans, “the total water on the surface of Earth (the oceans, the ice caps, the atmospheric water) makes up 0.025 percent of the mass of the planet—25/10,000ths of the stuff of Earth. If the Earth were the size of a Honda Odyssey minivan,” he clarifies, “the amount of water on the planet would be in a single, half-liter bottle of Poland Spring in one of the van’s thirteen cup holders.”

This is rather remarkably communicated by an illustration from the USGS, reproduced above, showing “the size of a sphere that would contain all of Earth’s water in comparison to the size of the Earth.” That’s not a lot of water.

Only vaguely related, meanwhile, there is an additional description in Fishman’s book worth repeating here.

[Image: The Orion nebula, photographed by Hubble].

[Image: The Orion nebula, photographed by Hubble].

In something called the Orion Molecular Cloud, truly vast amounts of water are being produced. How much? Incredibly, Fishman explains, “the cloud is making sixty Earth waters every twenty-four hours”—or, in simpler terms, “there is enough water being formed sufficient to fill all of Earth’s oceans every twenty-four minutes.” This is occurring, however, in an area “420 times the size of our solar system.”

Anyway, Fishman’s book is pretty fascinating, in particular his chapter, called “Dolphins in the Desert,” on the water reuse and filtration infrastructure installed over the past 10-15 years in Las Vegas.

(Via @USGS).

Lost Lakes of the Empire State Building

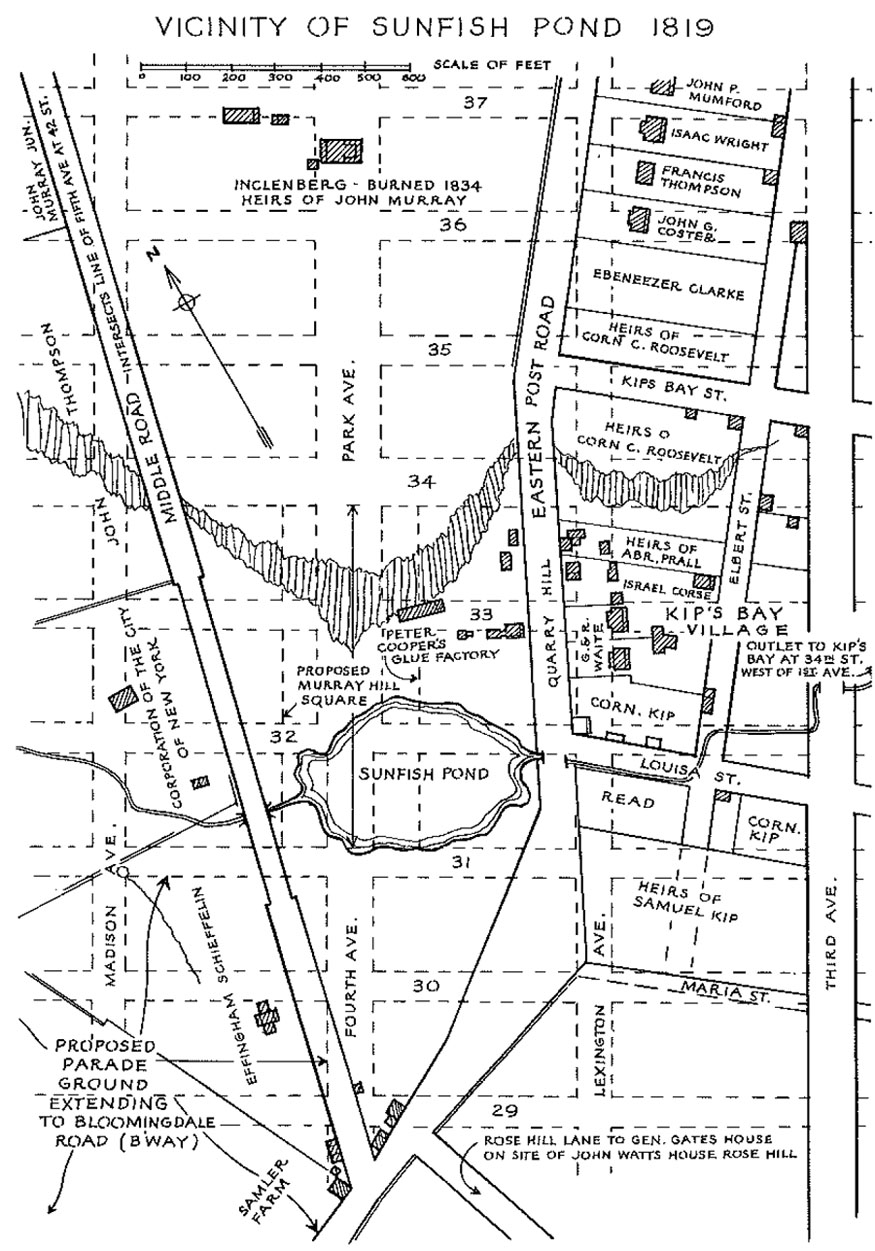

[Image: Sunfish Pond].

[Image: Sunfish Pond].

Something I’ve meant to post about for awhile—and that isn’t news at all—is the fact that there is a lost lake in the basement of the Empire State Building. Or a pond, more accurately speaking.

After following a series of links leading off from Steve Duncan’s ongoing exploration of New York’s “lost streams, kills, rivers, brooks, ponds, lakes, burns, brakes, and springs,” I found the fascinating story of Sunfish Pond, a “lovely little body of water” at the corner of what is now 31st Street and Fourth Avenue. “The pond was fed both by springs and by a brook which also carried its overflow down to the East River at Kip’s Bay.”

Interestingly, although the pond proper would miss the foundations of the Empire State Building, its feeder streams nonetheless pose a flood risk to the building: the now-buried waterway “leading from Sunfish Pond still floods the deep basement of the Empire State Building today.”

To a certain extent, this reminds me of a line from the recent book Alphaville: “Heat lightning cackles above the Brooklyn skyline and her message is clear: ‘You may have it paved over, but it’s still a swamp.'” That is, the city can’t escape its hydrology.

But perhaps this makes the Empire State Building as good a place as any for us to test out the possibility of fishing in the basements of Manhattan: break in, air-hammer some holes through the concrete, bust out fishing rods, and spend the night hauling inexplicable marine life out of the deep and gurgling darkness below.

Astrobiology and Drowned Nations

There’s a lot going on again this week at Studio-X NYC. Two quick things to put on your radar, in case you’re near New York:

[Image: NASA astrobiologist Lynn Rothschild measures solar radiation, via NASA].

[Image: NASA astrobiologist Lynn Rothschild measures solar radiation, via NASA].

1) Tonight at 6:30pm, we’ve got NASA astrobiologist Lynn Rothschild coming in to discuss her work, from extreme environments here on Earth, where scientists test for the limits of life, to the irradiated landscapes of Mars. We’ll look at the nature of biology, the possibilities for synthetic life, unexpected alternatives to DNA, and other mind-bending experiments that ask, in Rothschild’s words, “Where do we come from? Where are we going? and Are we alone?” Architect Ed Keller will be co-moderating this live interview.

2) Tomorrow, beginning at 6pm, we’ve got a massive line-up, including, I’m thrilled to say, an interview with Michael Gerrard, Andrew Sabin Professor of Professional Practice at Columbia Law School, discussing “drowning nations and climate change law. The list of whole countries at risk from sea-level rise is both extraordinary and growing, from the Marshall Islands to the Maldives, posing a series of unanswered questions about migration, citizenship, geopolitical power, and even the very definition of a state. As a 2010 article on ClimateWire asks, citing Gerrard’s work, “If a Country Sinks Beneath the Sea, Is It Still a Country?”

[Image: Male, capital of the Maldives, via Wikipedia].

[Image: Male, capital of the Maldives, via Wikipedia].

Gerrard was instrumental in organizing a conference last year called “Threatened Island Nations: Legal Implications of Rising Seas and a Changing Climate,” inspired by the “unique legal questions posed by rising oceans.” Central to our conversation tomorrow night will be what that last link calls “the sovereignty of submerged nations”:

Would the countries continue to have legal recognition like the Order of Malta, which ceded its island territory long ago but continues to be treated like a sovereign for some purposes? Would they retain their seats in the United Nations and other international bodies?

Here, it’s interesting to note recent suggestions that the “entire nation of Kiribati” might—or might not—move en masse to Fiji, to escape rising sea levels.

We will be interviewing Michael Gerrard only from 6-6:45pm, so don’t be late.

Immediately following that live interview, we will kick off a roundtable discussion on the future of sovereignty, governance, citizenship, and the nation-state, looking at a range of unique geographic and spatial scenarios, from the Arctic to the Internet. Joining us—many via Skype—will be: Benjamin Bratton, director of the Center for Design and Geopolitics at UC-San Diego; architect Ed Keller; Tom Cohen, co-editor with Claire Colebrook of the Critical Climate Change series from Open Humanities Press; science fiction novelist Peter Watts; architect and urbanist Adrian Lahoud, editor of Post-Traumatic Urbanism; and Dylan Trigg, author of, among other things, The Aesthetics of Decay.

Studio-X NYC is at 180 Varick Street, Suite 1610, 16th floor; here is a map. These events are free and open to the public, and no RSVP is required.

Performing Mars

[Image: Image via Karst Worlds].

[Image: Image via Karst Worlds].

An ice cave in Austria was recently used as a test landscape for experimental spacesuits and instrumentation systems—including 3D cameras—that might someday be used by humans on Mars.

The Dachstein ice cave was chosen, Stuff explains, “because ice caves would be a natural refuge for any microbes on Mars seeking steady temperatures and protection from damaging cosmic rays.”

[Images: (top and bottom) Photos by Katja Zanella-Kux; middle photos via Karst Worlds].

[Images: (top and bottom) Photos by Katja Zanella-Kux; middle photos via Karst Worlds].

Many images available at the Dachstein Mars Simulation Liveblog—including this series of 25 images courtesy of the Austrian Space Forum—document the testing process, which ranged from the beautifully surreal, as a fully space-suited man rolls strange devices down slopes of ice inside the planet, to the nearly postmodern, as crowds of normally dressed tourist onlookers are revealed at the edges of the show cave, watching this odd performance unfold.

And all this is in addition to the “obstacle course” developed for wearers of the spacesuit—reverse-engineering terrain from a particular type of clothing, or landscape design as an outgrowth from fashion—in the parking lot and nearby paved spaces of a research center in Austria. “The course included four snow-mountain passages, almost 40 meters of rock climbing and more than 60 meters of slushy snow terrain amongst others”—including “drawing bright ‘rocks’ to make the simulation happen” accurately.

Walking amidst painted representations of geology, wearing a suit designed for the atmosphere of another planet, and temporarily moving below the surface of the earth to throw pieces of specialty equipment down ice slopes, attached to ropes, the team was able to, by means of props and in William L. Fox’s words, “perform Mars on Earth.”

(Spotted via Karst Worlds).

Breaking Out and Breaking In Finale

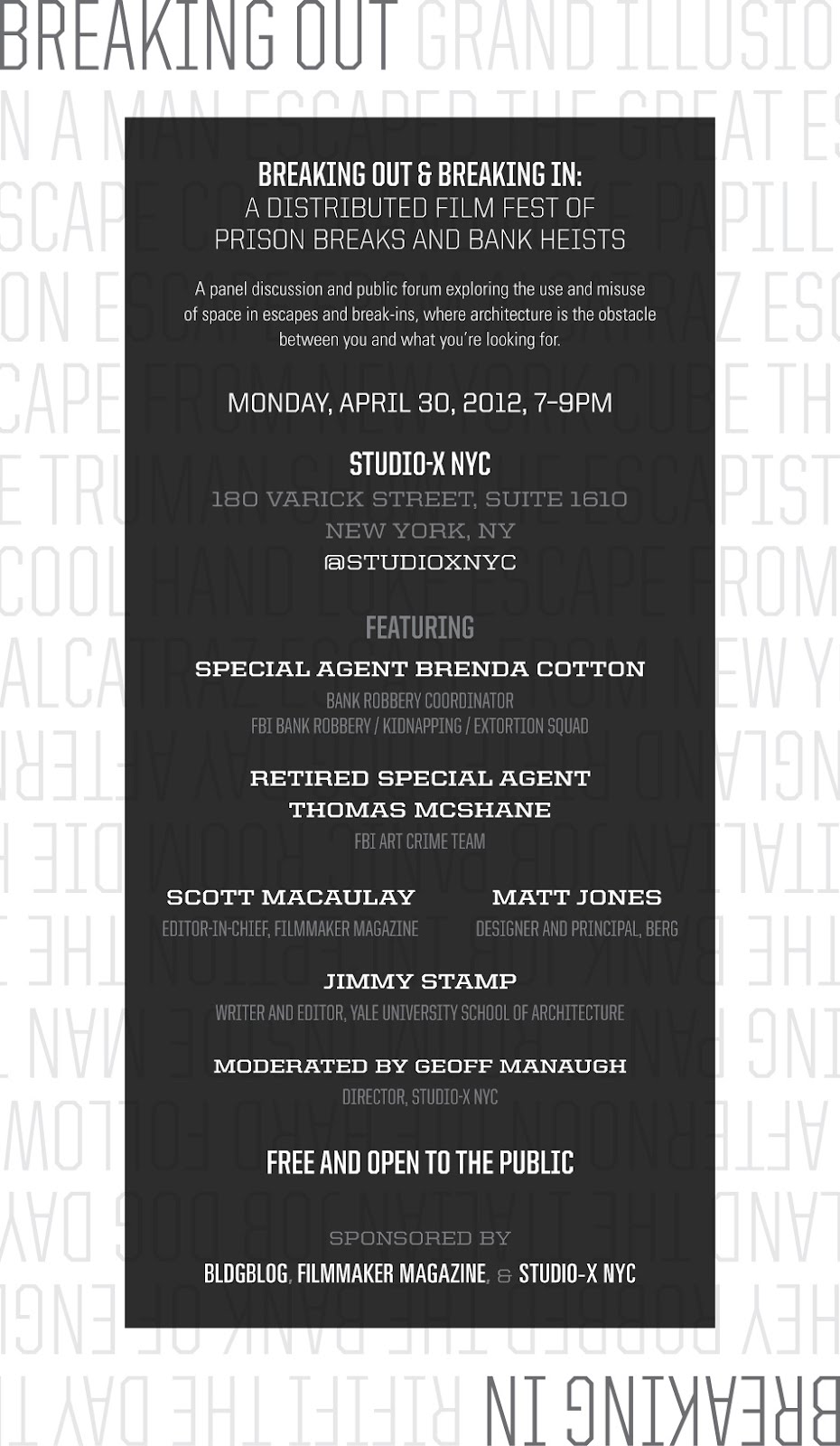

[Image: Poster design by Atley Kasky of Outpost].

[Image: Poster design by Atley Kasky of Outpost].

Although I hope to post again about the specific topics to be discussed at this event, I didn’t want to lose any more time in announcing the Breaking Out and Breaking In final public event to be hosted at Columbia University’s Studio-X NYC on Monday, April 30, featuring a unique and exciting panel of discussants drawn from the worlds of film, design, history, architecture, and the FBI.

Stop by to hear Special Agent Brenda Cotton, Bank Robbery Coordinator for the FBI’s Bank Robbery/Kidnapping/Extortion Squad; Thomas McShane, Retired FBI Special Agent from the Bureau’s Art Crime Team and co-author of Stolen Masterpiece Tracker; Scott Macaulay, editor-in-chief of Filmmaker Magazine, co-sponsors of the Breaking Out and Breaking In film festival; Matt Jones, designer and principal at BERG; and Jimmy Stamp, writer and editor at the Yale University School of Architecture and co-organizer of last year’s symposium on the architecture of the getaway, the hideout, and the coverup.

The event is free, open to the public, and kicks off on April 30 at 7pm sharp. We’ll be at 180 Varick Street, Suite 1610, on the 16th floor; here’s a map. Stop by for a panel discussion and open Q&A about the spatial scenarios of real and cinematic crimes, from armored car heists to panic rooms, from Boston art thefts to Los Angeles bank tunnels, and from the internal layouts of financial institutions to the unanticipated criminal side-effects of urban design, exploring the built environment from the perspective of the crimes that can be planned and foiled there.

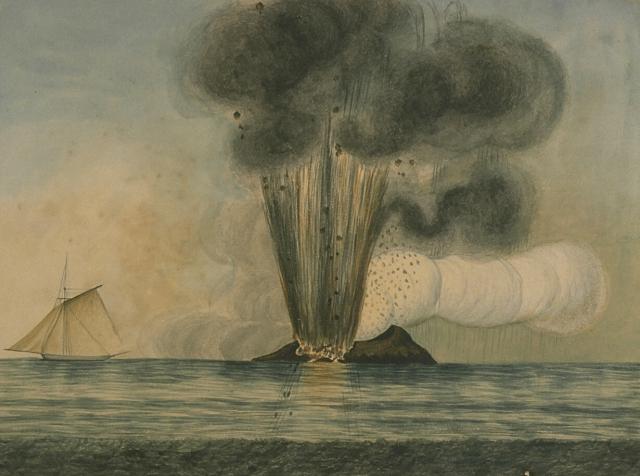

Ephemeral islands and other states-in-waiting

[Image: Temporary islands emerge from the sea, via].

[Image: Temporary islands emerge from the sea, via].

In the Mediterranean Sea southwest of Sicily, an island comes and goes. Called, alternately and among other names, depending on whose territorial interests are at stake, Graham Bank, Île Julia, the island of Ferdinandea, or, more extravagantly, a complex known as the Campi Flegrei del Mar di Sicilia (the Phlegraean Fields of the Sicily Sea), this geographic phenomenon is fueled by a range of submerged volcanoes. One peak, in particular, has been known to break the waves, forming a small, ephemeral island off the coast of Italy.

And, when it does, several nation-states are quick to claim it, including, in 1831, when the island appeared above water, “the navies of France, Britain, Spain, and Italy.” Unfortunately for them, it eroded away and disappeared beneath the waves in 1832.

It then promised to reappear, following new eruptions, in 2002 (but played coy, remaining 6 meters below the surface).

The island, though, always promises to show up again someday, potentially restarting old arguments of jurisdiction and sovereignty—is it French? Spanish? Italian? Maltese? perhaps a micronation?—so some groups are already well-prepared for its re-arrival. As Ted Nield explains in his book Supercontinent, “the two surviving relatives of Ferdinand II commissioned a plaque to be affixed to the then still submerged volcanic reef, claiming it for Italy should it ever rise again.” This is the impending geography of states-in-waiting, instant islands that, however temporarily, redraw the world’s maps.

The story of Ferdinandea, as recounted by that well-known primary historical source Wikipedia and seemingly ripe for inclusion in the excellent Borderlines blog by Frank Jacobs, is absolutely fascinating: it’s appeared on an ornamental coin, it was visited by Sir Walter Scott, it inspired a short story by James Fenimore Cooper, it was depth-charged by the U.S. military who mistook it for a Libyan submarine, and it remains the subject of active geographic speculation by professors of international relations. It is, in a sense, Europe’s Okinotori—and one can perhaps imagine some Borgesian wing of the Italian government hired to sit there in a boat, in open waters, for a whole generation, armed with the wizardry of surveying gear and a plumb bob dangling down into the sea, testing for seismic irregularities, as if casting a spell to coax this future extension of the Italian motherland up into the salty air.

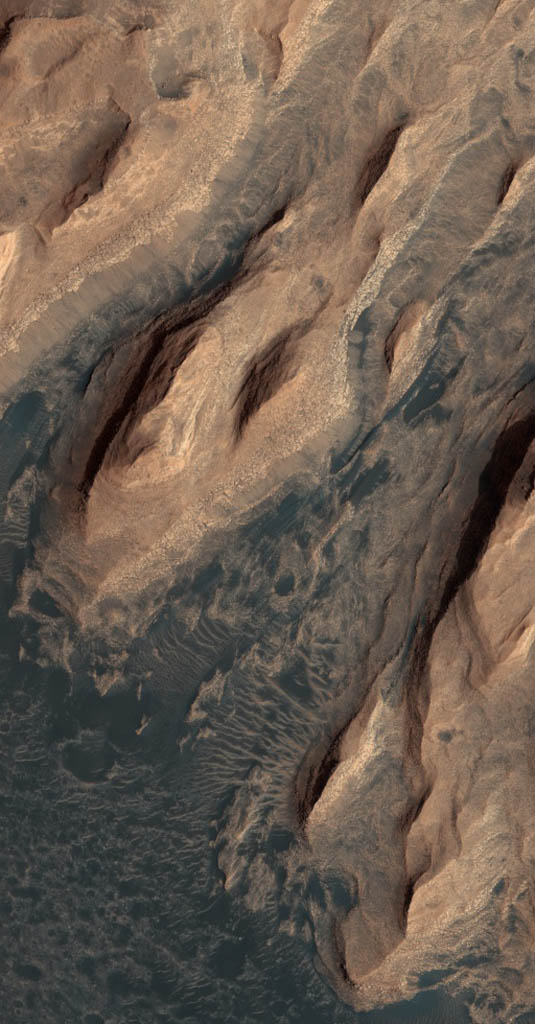

Glass Hills of Mars

More than 10 million square kilometers of landscape on the surface of Mars, a region nearly the size of Europe, is made of glass—specifically volcanic glass, “a shiny substance similar to obsidian that forms when magma cools too fast for its minerals to crystallize.”

[Image: An otherwise randomly grabbed image of Mars from the fantastic HiRISE site].

[Image: An otherwise randomly grabbed image of Mars from the fantastic HiRISE site].

In a paper called “Widespread weathered glass on the surface of Mars,” authors Briony Horgan and James F. Bell III, from the School of Earth and Space Exploration at Arizona State University, go on to suggest that “the ubiquitous dusty mantle covering much of the northern plains [of Mars] may obscure more extensive glass deposits” yet to be mapped.

Although it’s worth emphasizing that this glass is present mostly in the form of “Eolian” grains—that is, small pieces of windblown sand accumulating in dune fields—it is, nonetheless, a sublime scene to consider, with endless glass ridges and hills rolling off beneath stars and red dust storms, slippery to the touch, as hard as bedrock, cold, perhaps glistening and prismatic inside with distorted reflections of constellations, like blisters of light on a television screen coextensive with the surface of the planet. You could slide from one hill to the next, for hours—for days—alone on a frozen ocean of self-reflecting landforms, dizzy with the images locked within.

(What would a glass farm look like, agriculture carved into crystalline ridges, cultivating strange geologies? Meanwhile, ages ago, in a different lifetime on BLDGBLOG: Mount St. Helens of Glass).