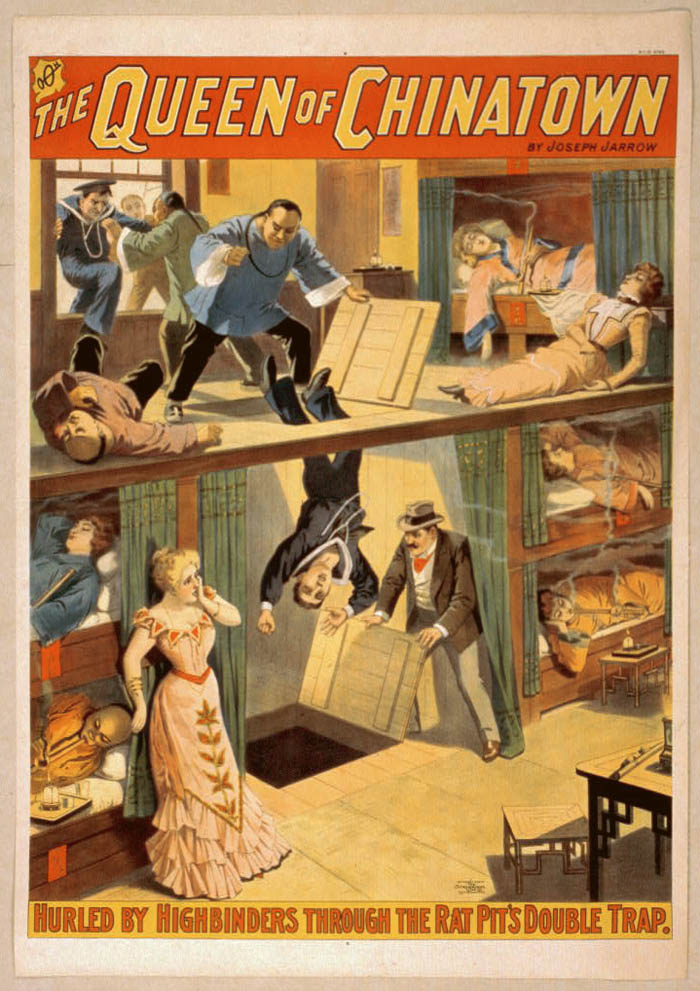

[Image: Poster for “The Queen of Chinatown” by Joseph Jarrow, courtesy of the Library of Congress].

[Image: Poster for “The Queen of Chinatown” by Joseph Jarrow, courtesy of the Library of Congress].

Someone should write a short history of the trapdoor as a spatial plot device in Broadway plays, literary fiction, Hollywood thrillers, dreams, CIA plots, and more. How does the trapdoor—as an unexpected space of strategic perforation and architectural connection—serve to move a plot forward and to give spatial form to characterization?

The “Queen of Chinatown” poster seen above, for instance, with its sprung floor collapsing beneath the weight of a hapless sailor, seems to promise an entire urban district—“Chinatown” as an Orientalist fantasy of inscrutable passageways and other devious spatial practices—illicitly Swiss-cheesed with unexpected wormholes. Chutes, pits, wells, and shafts are perhaps distributed throughout the neighborhood, we’re led to imagine, giving the erstwhile “Queen” her strategic mastery of the area. Chinatown becomes a hive of “mysterious Chinese tunnels,” a porous space guarded not through high fortress walls or even by watchmen or CCTV, but through a camouflaged network of surprise openings, like architectural sinkholes, that no one can predict and of which only one person knows the true extent.

That poster suggests an alternative version of Christopher Nolan’s recent heist film, Inception: there are opium addicts slumbering in a warren of stacked bunkbeds in an off-the-books Chinatown dream academy, and there is a man—an anonymous investigative agent of the state—crashing through the floor into this world of broadly Asiatic decor. A multi-layered hive of architectural space seen sliced through in section, where trapdoors lead to further trapdoors. Inception as an 1890s heist caper, serialized on the popular stage.

[Image: A still from Inception, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Image: A still from Inception, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

In any case, a spatial history of trapdoors—in film, literature, myth, dreams, and theater—would make an amazing pamphlet or book, perhaps part of a larger series of pamphlets looking at other minor architectural typologies—like log flumes and National Park trail structures and hay mazes.

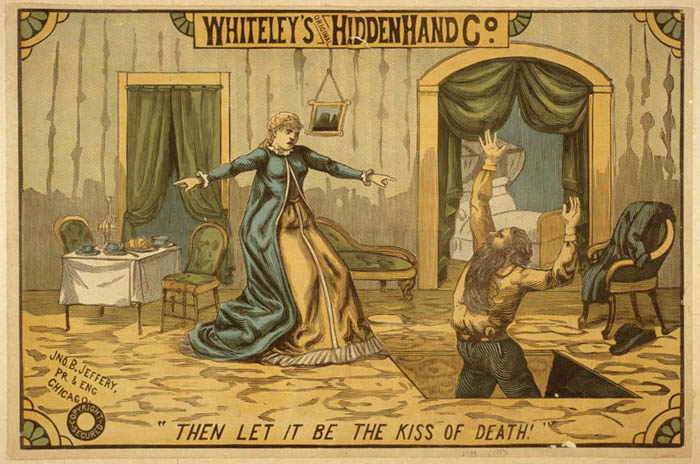

[Image: “Then let it be the kiss of death!” Courtesy of the Library of Congress].

[Image: “Then let it be the kiss of death!” Courtesy of the Library of Congress].

The two posters reproduced here, both available through the Library of Congress, are at least one place to start.

See also Michel Gondry's Smirnoff ad, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3SdlAXq45VY, which was somewhat recycled for Being John Malkovich (TBH I thought the ad was Jonze too).

Great idea! I love it. You should continue this. Give yourself a year to complete it. -Wrongtable

Mitchell and Webb with a trap door built to code: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ipaf-NXqF7Q

Geoff,

You might be interested in a piece I wrote for Bright Lights Film Journal on the spatial imagination of the film 'Confessions of an Opium Eater' (there's a reference to your "Mysterious Chinese Tunnels" post). http://www.brightlightsfilm.com/71/71confessions_nortz.php

Also, there was a charming little book written around 1900 called "Secret Chambers and Hiding Places" which is available online (http://www.gutenberg.org/files/13918/13918-h/13918-h.htm). It's Anglo-centric, but it's about the only book length treatment of the topic…

Maybe it should be mentioned that the cover of "The Queen of Chinatown" shows the so called "Shanghaiing" meaning to force sailors into service.

But anyway, thanks a lot for the wonderful images.

TV Tropes [http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/TrapDoor] has a great summary of the use of trapdoors in film and literature. Would be a great research project.

Not forgetting Middleton's 1657 Jacobean play "Women Beware Women", in which the villain is killed by his own trap: a trapdoor in the floor with a large caltrop underneath it.

I'm surprised that I get the opportunity to be the first to mention this:

"BERK!! Where's my breakfast?"

If you're British, and over 30, the mention of the word trapdoor can mean only one thing.

http://www.80scartoons.co.uk/trapdoor2.php

The screenshot also looks like Nolan wanted to return to the set of The Prestige (where the trapdoor is actually a red herring).