Ten quick links for a Monday morning:

[Image: Photo by Richard Caplan for City Limits].

[Image: Photo by Richard Caplan for City Limits].

—An “African burial ground” lies beneath the floor of a bus depot in Harlem, City Limits reports, but “the only stone slab at the site [marking its historical importance] is the concrete floor of the Metropolitan Transit Authority bus garage sitting on top of tons of fill mingled with human remains.” That is subject to change, however, as “the Harlem African Burial Ground Task Force—composed of church leaders, activists, historians and elected officials—seeks preservation and official recognition of the colonial-era cemetery.” As DNAinfo.com adds, “Community members feared upcoming reconstruction of the bus depot, slated to begin in 2015, along with ongoing construction of the Willis Avenue Bridge, could disturb the remains of its former African burial ground located between 126th and 127th Streets along First Avenue.”

[Image: Eleusis, Greece, courtesy of the UCLA Archaeology Field Program].

[Image: Eleusis, Greece, courtesy of the UCLA Archaeology Field Program].

—If I had a spare $8,000, I’d sign up for the UCLA Archaeology Field Program’s Eleusis 3D Archaeological Recording and Visualization Project: “Eleusis is world famous as the location of the Eleusinian Mysteries—a significant Athenian religious festival—and is located some 14 miles west of Athens opposite the island of Salamis. The students will record the site’s extensive architectural remains using terrestrial laser scanning, photogrammetry, GIS and GPS. 3D computer visualization and animation technologies will be used to re-create areas of the site.”

[Image: Dubai’s abandoned Arabian Canal project: “The Arabian Canal was meant to run for 75 kilometres through the desert,” photographer Tom Gara explains, “surrounded by luxury villas and apartment towers, creating an entire new city and doubling the size of Dubai”].

[Image: Dubai’s abandoned Arabian Canal project: “The Arabian Canal was meant to run for 75 kilometres through the desert,” photographer Tom Gara explains, “surrounded by luxury villas and apartment towers, creating an entire new city and doubling the size of Dubai”].

—”It will require an army of 10,000 construction workers, hundreds of giant drills and bulldozers, and four years of digging to get the job done,” we read courtesy of The National back in 2008. “A billion cubic metres of earth will be removed from the ground and turned into hills that rise as high as the Emirates Towers Hotel.”

The 75-kilometre-long Arabian Canal will join the ranks of the great civil engineering legends of the earth—like the Suez and Panama canals. Yet, unlike its predecessors, Dubai’s new US$11bn (Dh40.4bn) canal is being dug solely for its value to property development. On its banks a new city will rise with museums, hotels, apartment buildings, villas, shops—and a population of 1.5 million people.

Unfortunately, it is now a ruin—or, more properly speaking, an abandoned excavation cut through the Earth like a little-known desert work by Michael Heizer.

[Image: The shallow acidic lakes of desert Australia, courtesy of NASA-JSC].

[Image: The shallow acidic lakes of desert Australia, courtesy of NASA-JSC].

—”Life not only survives but thrives in Australian lakes where conditions may be as harsh as those on ancient Mars,” New Scientist reports. “The lakes are very shallow and periodically fill with rainwater before partially evaporating, which concentrates the salts within them. They may be the closest equivalents on Earth of the shallow pools thought to have once dotted Mars.”

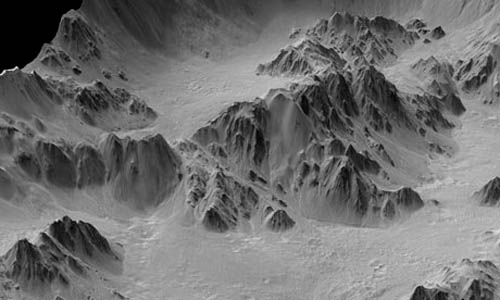

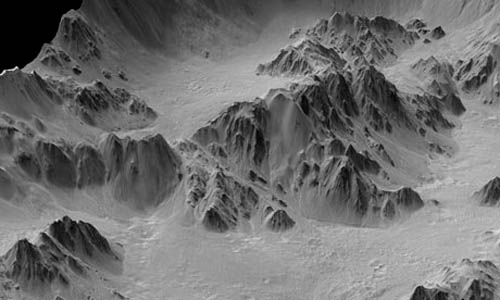

[Image: Cliffs of Mars, courtesy of NASA].

[Image: Cliffs of Mars, courtesy of NASA].

—Speaking of Mars, “the new Mars pictures are a confrontation with the sublime,” Sam Leith opines in the Guardian. “Look at these photographs of Mars, and you often can’t tell if you’re looking at miles, or metres, or microns. It’s a scale with nothing human to anchor it. It suggests an unsettling kinship between the alienness of both the very tiny and the very large.”

[Image: “A floating container vessel used by the UK during the 1982 Falklands War,” courtesy of Popular Science].

[Image: “A floating container vessel used by the UK during the 1982 Falklands War,” courtesy of Popular Science].

—The ever-awesome Popular Science—whose Twitter feed is well-worth following—explains that “a modular, self-assembling floating platform delivered by cargo ships could provide a cheaper naval base for military forces” in their battle against piracy. Making BLDGBLOG’s long-stated comparisons between Archigram and DARPA seemingly explicit, the “Tactically Expandable Maritime Platform (TEMP),” as it’s known, “would turn the standard ISO containers carried by cargo ships into modules that each serve a specific purpose, such as living quarters, command cells, comm shacks, or weapons stations. Once deployed by cargo ship, the self-propelling modules would use low-level computer brains to assemble themselves into a larger structure.” Mobile, modular, military instant cities at sea. Read a bit more at The Register.

[Image: A glimpse of an Aquapod floating fish farm, courtesy of National Geographic].

[Image: A glimpse of an Aquapod floating fish farm, courtesy of National Geographic].

—For a variety of reasons, that previous story reminds me of this report from National Geographic last summer: “In the future, giant, autonomous fish farms may whir through the open ocean, mimicking the movements of wild schools or even allowing fish to forage ‘free range’ before capturing them once again.” See more images here—and, in the process, read Pruned‘s 2008 take on the Aquapod farm module.

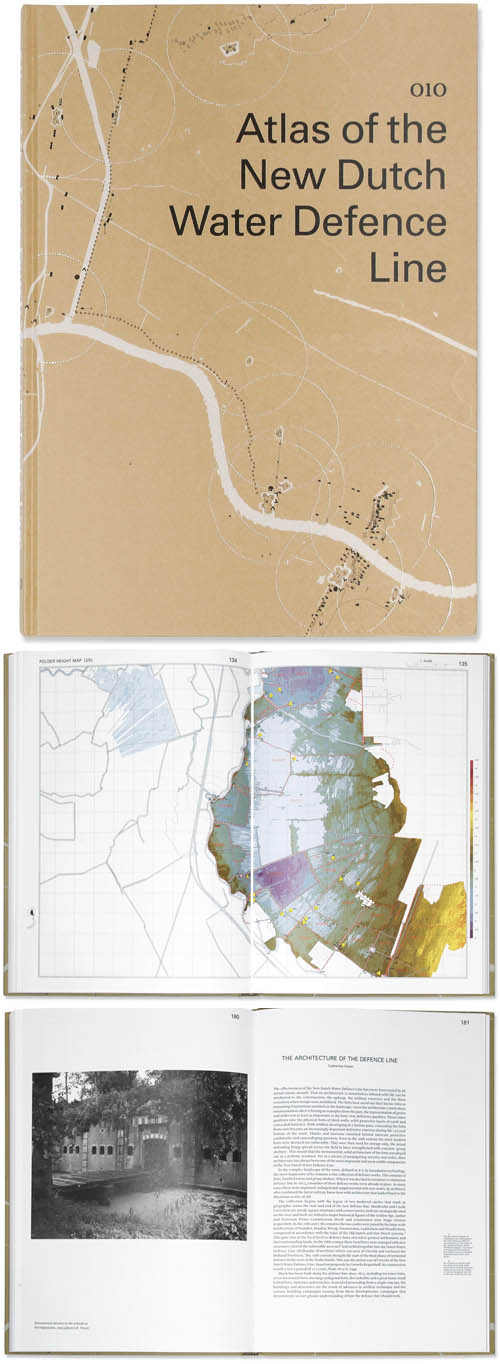

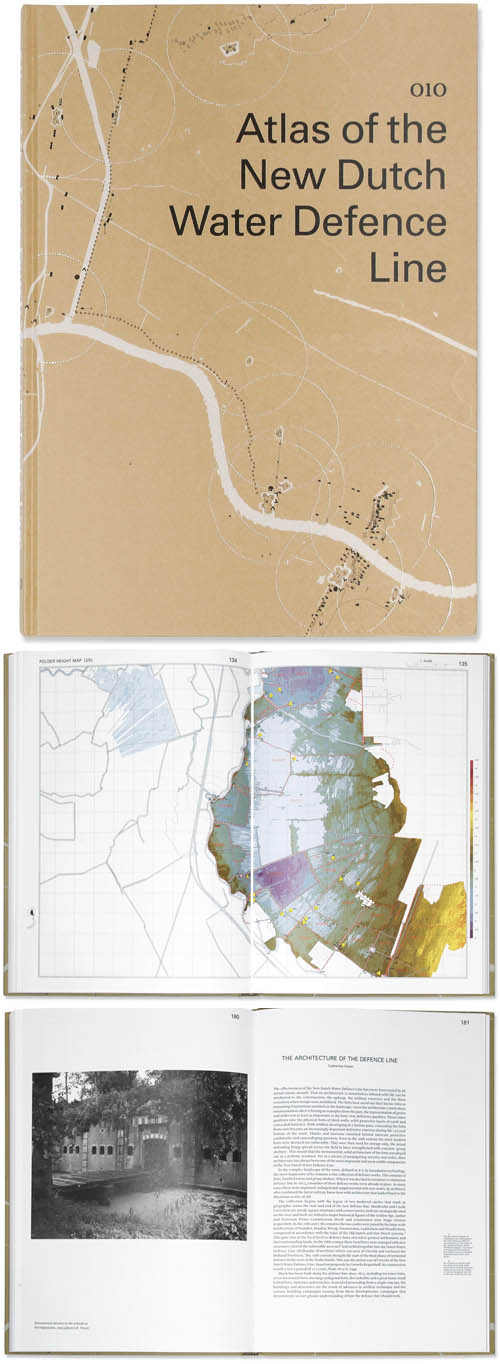

[Images: From Atlas of the New Dutch Water Defense Line].

[Images: From Atlas of the New Dutch Water Defense Line].

—I really want to read this book, but I have yet to find a copy: Atlas of the New Dutch Water Defense Line.

This atlas addresses the New Dutch Water Defense Line (Nieuwe Hollandse Waterlinie) on a themed basis. Its position in the landscape, the forts, the inundation system, the geomorphology, the strategic system and recent developments can be read off in maps rendered so as to give an understanding of all aspects of the defense line landscape. The defense line reveals itself as a many-tentacled military defensive system of forts, group shelters and polders which can be flooded at the threat of war. The maps show the cohesion of the defense line as a landscape-strategic structure as well as the topographic composition of this structure in layers and components. The more detailed maps of the forts display the wealth of historic places, insertions in the landscape and defining elements.

It’s beautifully designed, as well.

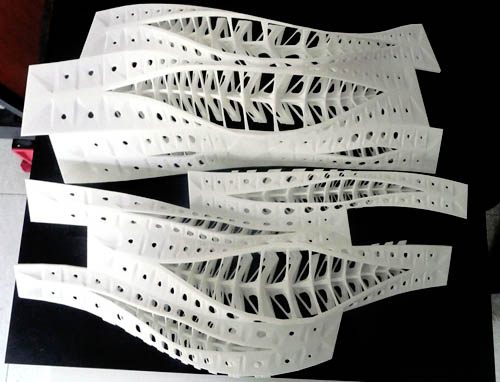

[Image: From a project by nARCHITECTS].

[Image: From a project by nARCHITECTS].

—”Abandoned neighborhoods. Boarded-up harbor facilities. An oil refinery submerged under several feet of brackish water. The Statue of Liberty slowly sinking into the sea. ‘Rising Currents: Projects for New York’s Waterfront,’ a new show at the Museum of Modern Art, reflects a level of apocalyptic thinking about this city that we haven’t seen since it was at the edge of financial collapse in the 1970s,” writes the beleaguered architecture critic for the New York Times. The show—open now through October 11, 2010—includes work by ARO and dlandstudio, LTL Architects, Matthew Baird Architects, nARCHITECTS, and SCAPE.

[Image: Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty, courtesy of Geographical].

[Image: Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty, courtesy of Geographical].

—Finally, “an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) is exactly what it says it is,” Geographical magazine explains: “a precious landscape whose distinctive character and natural beauty are so outstanding that it is in the nation’s interest to safeguard them.” Check out Geographical‘s guide to the UK’s 40 official sites of Outstanding Natural Beauty, including the Ring of Gullion, the Sperrins, the dams and ruins of Nidderdale, the abandoned mines of the Tamar Valley, and many more.

(Some links via Archaeology. Don’t miss Quick Links 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8).

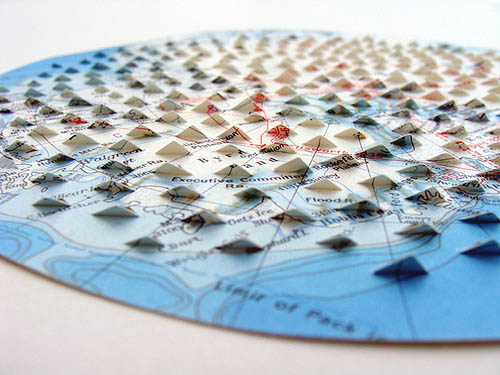

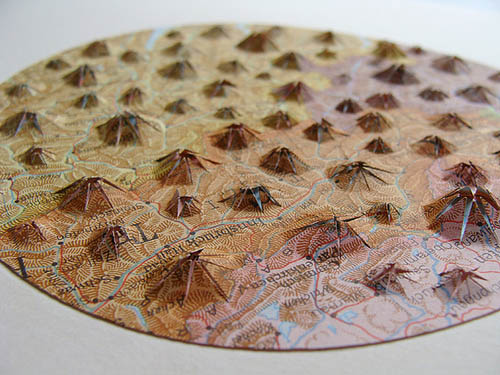

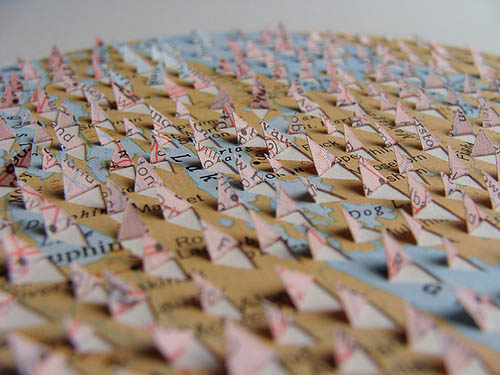

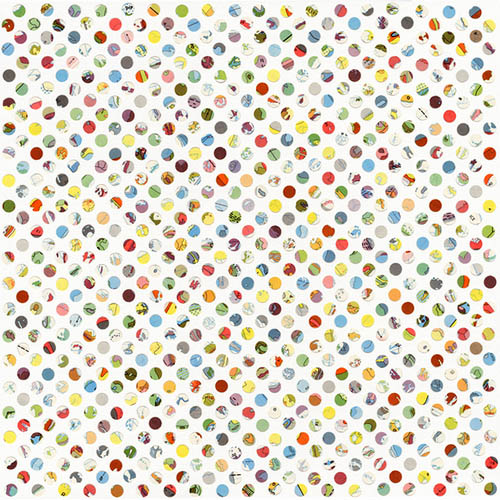

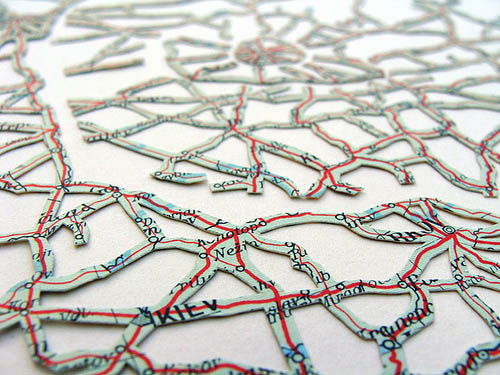

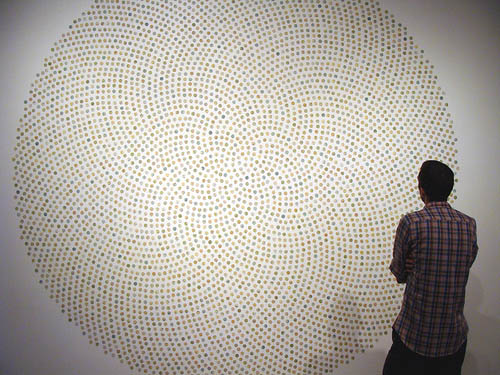

[Image: From Trophy Hunter by Bryan Christiansen, on display at the Nevada Museum of Art till May 9].

[Image: From Trophy Hunter by Bryan Christiansen, on display at the Nevada Museum of Art till May 9]. [Image: From Trophy Hunter by Bryan Christiansen at the Nevada Museum of Art].

[Image: From Trophy Hunter by Bryan Christiansen at the Nevada Museum of Art]. [Image: Trophy Hunter by Bryan Christiansen at the Nevada Museum of Art].

[Image: Trophy Hunter by Bryan Christiansen at the Nevada Museum of Art].

[Images: From Trophy Hunter by Bryan Christiansen at the Nevada Museum of Art].

[Images: From Trophy Hunter by Bryan Christiansen at the Nevada Museum of Art].

[Images: Trophy Hunter by Bryan Christiansen, on display at the Nevada Museum of Art].

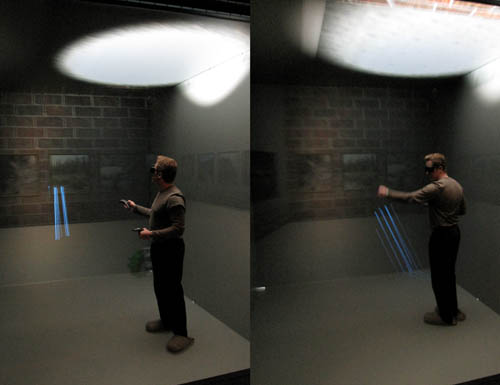

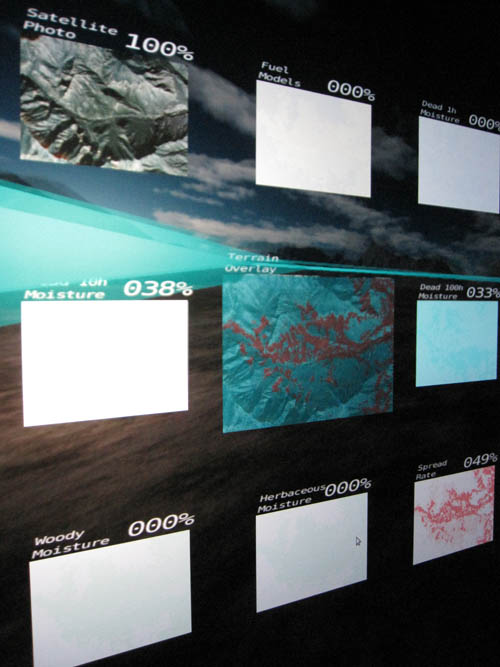

[Images: Trophy Hunter by Bryan Christiansen, on display at the Nevada Museum of Art]. [Image: The CAVE at the Desert Research Institute in Reno, now called the

[Image: The CAVE at the Desert Research Institute in Reno, now called the

[Image: Daniel Coming, Principle Investigator of the

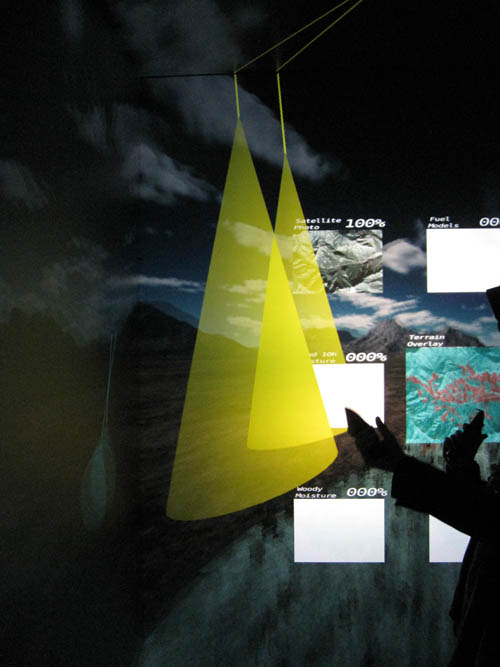

[Image: Daniel Coming, Principle Investigator of the  [Image: Touring virtual light].

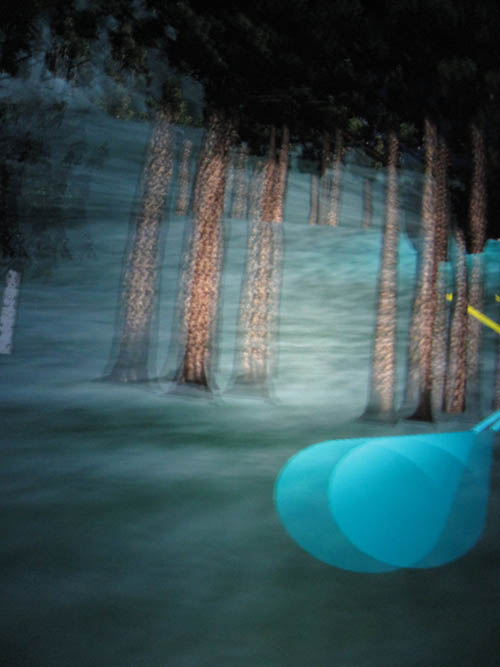

[Image: Touring virtual light].

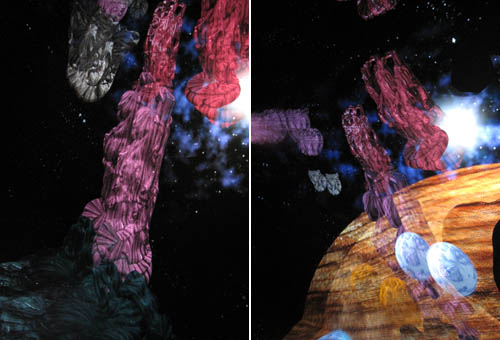

[Image: Cthulhoid satellites appear in space before you, rotating three-dimensionally in silence].

[Image: Cthulhoid satellites appear in space before you, rotating three-dimensionally in silence].

[Images: Photos by BLDGBLOG and

[Images: Photos by BLDGBLOG and  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: Work by

[Image: Work by  [Image: Work by

[Image: Work by

[Images:

[Images:  [Image: By

[Image: By

[Images: All works by

[Images: All works by  [Image: By

[Image: By

[Images: All works by

[Images: All works by  [Image: Work by

[Image: Work by

[Images: By

[Images: By  [Image: Map via University of Maine

[Image: Map via University of Maine  [Image: U.S. helicopter over Baghdad,

[Image: U.S. helicopter over Baghdad,  [Image: Photo by Richard Caplan for

[Image: Photo by Richard Caplan for  [Image: Eleusis, Greece, courtesy of the

[Image: Eleusis, Greece, courtesy of the  [Image: Dubai’s abandoned Arabian Canal project: “The Arabian Canal was meant to run for 75 kilometres through the desert,” photographer

[Image: Dubai’s abandoned Arabian Canal project: “The Arabian Canal was meant to run for 75 kilometres through the desert,” photographer  [Image: The shallow acidic lakes of desert Australia, courtesy of NASA-JSC].

[Image: The shallow acidic lakes of desert Australia, courtesy of NASA-JSC]. [Image: Cliffs of Mars, courtesy of NASA].

[Image: Cliffs of Mars, courtesy of NASA]. [Image: “A floating container vessel used by the UK during the 1982 Falklands War,” courtesy of

[Image: “A floating container vessel used by the UK during the 1982 Falklands War,” courtesy of  [Image: A glimpse of an

[Image: A glimpse of an  [Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From a project by

[Image: From a project by  [Image: Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty, courtesy of

[Image: Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty, courtesy of  [Image: Thesis project by Vincenzo Reale, from a course taught by Alessio Erioli at the University of Bologna; photo by

[Image: Thesis project by Vincenzo Reale, from a course taught by Alessio Erioli at the University of Bologna; photo by  [Image: Thesis project by Riccardo La Magna, from a course taught by Alessio Erioli at the University of Bologna; photo by

[Image: Thesis project by Riccardo La Magna, from a course taught by Alessio Erioli at the University of Bologna; photo by  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From the

[Image: From the  [Image: Inside

[Image: Inside

[Images: Cladding for

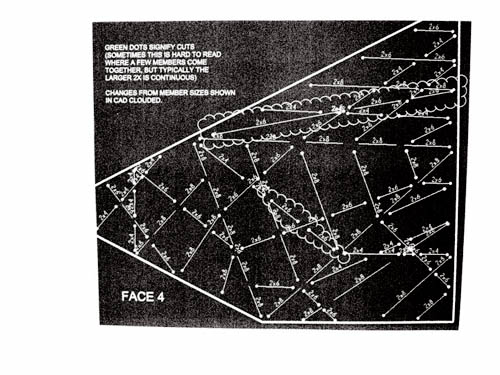

[Images: Cladding for  [Images: Assembly diagrams for

[Images: Assembly diagrams for