I was in Maastricht, Netherlands, for a couple nights last week, mostly as a way to break-up my trip across the Atlantic and thus help get over jet-lag before attending an archaeology conference (where I currently type this).

I went specifically to Maastricht, however, because it’s home to an astonishing number of subterranean sites, from 800-year-old limestone mines and 17th-century star fortifications to NATO defense bunkers. I basically checked into my hotel then disappeared underground for the rest of the visit.

Here are some pics.

My morning started here, at the entrance to the Casemates Waldeck, a labyrinth of defensive earthworks complete with tunnels, counter-mine tunnels, barracks, and firing positions. Large parts of the system were then later repurposed as civilian air-raid shelters during WWII.

The geometric logic of the forts was—among other things—to lure enemy attackers in over cliff-like artificial drops and ridges, thinking they were on their way to the heart of the city. However, this simply trapped them between huge brick walls, directly in front of disguised gun emplacements, many of which were deliberately aimed at stomach-height to maximize suffering.

If you go through the door seen in the above photographs, meanwhile, you end up inside a bewildering system of multi-level tunnels weaving around for kilometers beneath the outer edge of the city.

Because the city has expanded and grown over the centuries, whole neighborhoods now sit atop these structures; if you live in Maastricht, you might very well have disused military fortification tunnels running under your basement.

What’s more, not all of the tunnels are mapped—which means that some are neither maintained nor stabilized. Apparently, seasonal floods have led to sinkholes above, as streets partially collapse into the system.

And that’s just one of many, many underground sites you can tour.

The next place I headed was called the Zonneberg Caves—which are not natural caves, but a colossal limestone mine—and I honestly can say I would spend entire weeks down there.

I’m just randomly typing facts from memory, because I’m on a break from a conference and want to get these photos up, which means I will almost certainly get a few details wrong, but I believe they said that “only” 80 or so kilometers of these ancient limestone mines remain from more than 200, and that the first shafts were cut in the 13th century.

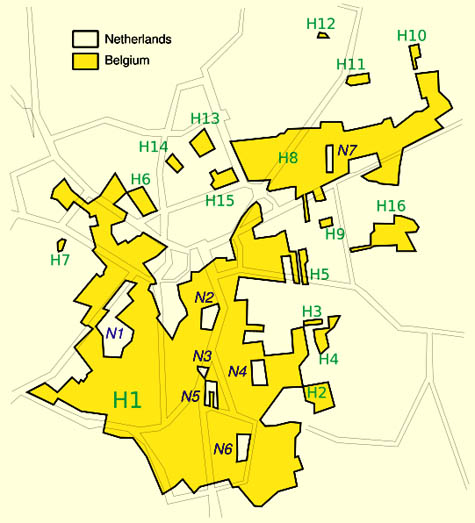

The mines extend all the way over the international border into Belgium. The Belgian tunnels are apparently closed to the public, yet people sneak into them all the time.

There are 20th-century artworks painted on the walls, much older graffiti etched directly into rock, and massive corridors extending off on all sides into darkness.

If you’re into the underground and ever have an opportunity to spend more time than a tour down there, I would recommend it without any hesitation—and I will be deeply, deeply jealous.

The site is even complete with a little church altar.

Bear in mind, this is all still the same day.

The next site I went to was accessed through a locked metal door in the rock (pictured above). This system, known as the North Caves, is actually physically connected to the Zonneberg Caves, although it would take an hour or more to get between them underground. Like I say, I would go back there and wander around in a heartbeat.

The added interest of this latter system is that parts of it were used during WWII to house paintings by the Old Masters, protecting them from Nazi plunder and stray Allied bombs alike.

At the end, you go into a place called “the Vault” to see where Rembrandts and other paintings were hung while war waged above.

Finally, after many hours underground, I walked outside—and the first thing I saw was this rainbow. A cheesily enjoyable end to a fantastic day.

If you’re tempted to see any of these places yourself, and you hope to do so legally, check out Maastricht Underground for potential tours.

[All photos by Geoff Manaugh/BLDGBLOG.]

[Image: Proposal for a converted

[Image: Proposal for a converted  [Image: Proposal for a converted

[Image: Proposal for a converted  [Image: Proposal for a converted

[Image: Proposal for a converted  [Image: Cabin by

[Image: Cabin by  [Image: Cabin by

[Image: Cabin by

[Images: Cabin by

[Images: Cabin by  [Image: Cabin by

[Image: Cabin by  [Image: The strange, island-like spaces of micro-sovereignty within the town of

[Image: The strange, island-like spaces of micro-sovereignty within the town of