[Image: River valley outside Kamdesh, Afghanistan, where the “Battle of Kamdesh” occurred, an assault that loosely serves as the basis for part of John Renehan’s novel, The Valley].

[Image: River valley outside Kamdesh, Afghanistan, where the “Battle of Kamdesh” occurred, an assault that loosely serves as the basis for part of John Renehan’s novel, The Valley].

While we’re on the subject of books, an interesting novel I read earlier this year is The Valley by John Renehan. It’s a kind of police procedural set on a remote U.S. military base in the mountains of Afghanistan, fusing elements of investigative noir, a missing-person mystery, and, to a certain extent, a post-9/11 geopolitical thriller, all in one.

Architecturally speaking, the book’s includes a noteworthy scene quite late in the book—please look away now if you’d like to avoid a minor spoiler—in which the main character attempts to learn why a particularly isolated valley on the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan seems so unusually congested with insurgent fighters and other emergent sources of local conflict.

He thus hikes his way up through heavily guarded opium fields to what feels like the edge of the known world, as the valley he’s tracking steadily narrows ever upward until “there were no more river sounds. He’d gotten above the springs and runoff that fed it.” In the context of the novel, this scene feels as if the man has stepped off-stage, ascending to a world of solitude, clouds, and mountain silence.

[Image: Photo courtesy U.S. Army, taken by Staff Sergeant Adam Mancini].

[Image: Photo courtesy U.S. Army, taken by Staff Sergeant Adam Mancini].

What he sees there, however, is that the entire valley, in effect, has been quarantined. A baffling and massive concrete wall has been constructed by the U.S. military across the entire pass, severing the connection between two neighboring countries and forming an absolute barrier to insurgent troop movements. The wall has also decimated—or, at least, substantially harmed—the local economy.

Attempts to blow it up have left visible scars on its flanks. It has become a blackened super-wall, one so far away from regional villages that many people don’t even know it’s there; they only know its side-effects.

“It was an impressive construction,” Renehan writes. “There was no way they got vehicles all the way up here. It must have been heavy-lift helicopters laying in all the pieces and equipment.”

[Image: U.S. military helicopter in Afghanistan, courtesy U.S. Army, taken by by Staff Sgt. Marcus J. Quarterman].

[Image: U.S. military helicopter in Afghanistan, courtesy U.S. Army, taken by by Staff Sgt. Marcus J. Quarterman].

It was a titanic undertaking, “a wall of walls,” in his words, an improvised barrier like something out of Mad Max:

Concrete blast barriers lined up twenty feet high, one against another on the slanting ground, shingled all across the gap, with another layer of shorter walls piled haphazardly atop, and more shoring up the gaps at the bottom. There must have been another complete set of walls built behind the one he could see, because the whole hulking thing had been filled with cement. It had oozed and dried like frosting at the seams, puddling through the gaps at the bottom.

The man puts his hand on the concrete, knowing now that the whole valley had simply been sealed off. It “was closed.”

There are many things that interest me here. One is this notion that a distant megastructure, of which few people are aware, nonetheless exhibits direct and tangible effects on their everyday lives; you might not even know such a structure exists, in other words, but your life has been profoundly shaped by it. The metaphoric possibilities here are obvious.

[Image: Photo courtesy U.S. Army, taken by Spc. Ken Scar, 7th MPAD].

[Image: Photo courtesy U.S. Army, taken by Spc. Ken Scar, 7th MPAD].

But I was also reminded of another famous military wall constructed in a remote mountain landscape to keep a daunting adversary at bay, the so-called “Alexander’s Gates,” a monumental—and entirely mythic—architectural project allegedly built by Alexander the Great in the Caucasus region to keep monsters out of Europe. This myth was the Pacific Rim of its day, we might say.

I first encountered the story of Alexander’s Gates in Stephen T. Asma’s book, On Monsters.

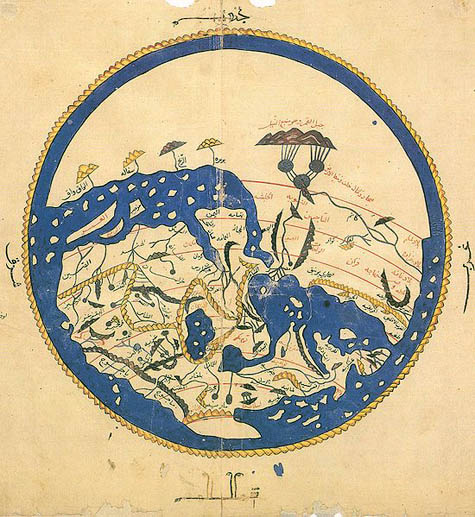

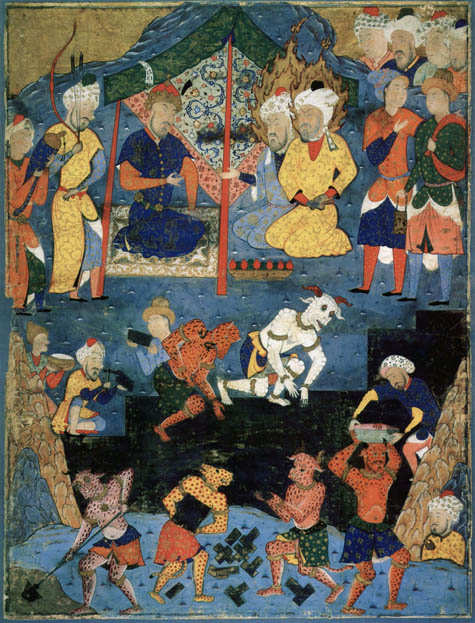

Alexander supposedly chased his foreign enemies through a mountain pass in the Caucasus region and then enclosed them behind unbreachable iron gates. The details and the symbolic significance of the story changed slightly in every medieval retelling, and it was retold often, especially in the age of exploration. (…) The maps of the time, the mappaemundi, almost always include the gates, though their placement is not consistent. Most maps and narratives of the later medieval period agree that this prison territory, created proximately by Alexander but ultimately by God, houses the savage tribes of Gog and Magog, who are referred to with great ambiguity throughout the Bible, and sometimes as individual monsters, sometimes as nations, sometimes as places.

On the other side of Alexander’s Gates was what Asma memorably calls a “monster zone.”

[Image: Photo courtesy U.S. Army, taken by U.S. Army Pfc. Andrya Hill, 4th Brigade Combat Team].

[Image: Photo courtesy U.S. Army, taken by U.S. Army Pfc. Andrya Hill, 4th Brigade Combat Team].

In any case, you can learn a bit more about the gates in this earlier post on BLDGBLOG, but it instantly came to mind while reading The Valley.

Renehan’s bulging “wall of walls,” constructed by U.S. military helicopters in a hostile landscape so remote it is all but over the edge of the world, purely with the goal of sealing off an entire mountain valley, is a kind of 21st-century update to Alexander’s Gates.

In fact, it makes me wonder what sorts of megastructures exist in contemporary global military mythology—what urban legends soldiers tell themselves and each other about their own forces or those of their adversaries—from underground super-bunkers to unbreachable desert walls. What are the Alexander’s Gates of today?

[Image: The Dariel Pass in the Caucausus Mountains, rumored possible site of the mythic

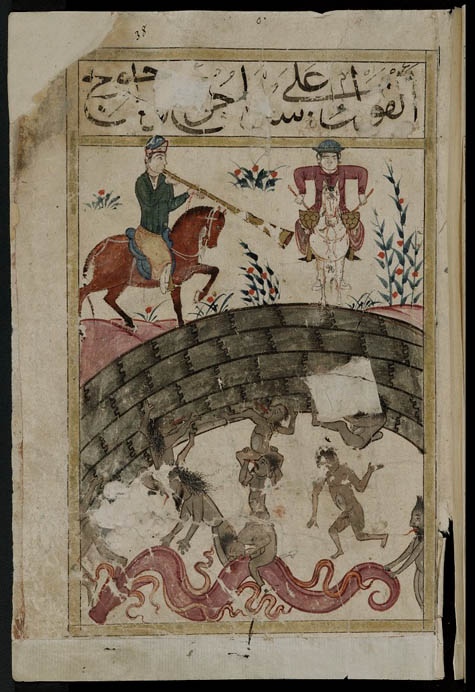

[Image: The Dariel Pass in the Caucausus Mountains, rumored possible site of the mythic  [Image: Constructing the wall of Dhul-Qarnayn, mythic isotope to Alexander’s Gates].

[Image: Constructing the wall of Dhul-Qarnayn, mythic isotope to Alexander’s Gates]. [Image: The geography of Us vs. Them, in a “12th century map by the Muslim scholar Al-Idrisi. ‘Yajooj’ and ‘Majooj’ (Gog and Magog) appear in Arabic script on the bottom-left edge of the Eurasian landmass, enclosed within dark mountains, at a location corresponding roughly to Mongolia.” Via

[Image: The geography of Us vs. Them, in a “12th century map by the Muslim scholar Al-Idrisi. ‘Yajooj’ and ‘Majooj’ (Gog and Magog) appear in Arabic script on the bottom-left edge of the Eurasian landmass, enclosed within dark mountains, at a location corresponding roughly to Mongolia.” Via  [Image: Constructing the wall of Dhul-Qarnayn, via

[Image: Constructing the wall of Dhul-Qarnayn, via  [Image: A map of the

[Image: A map of the