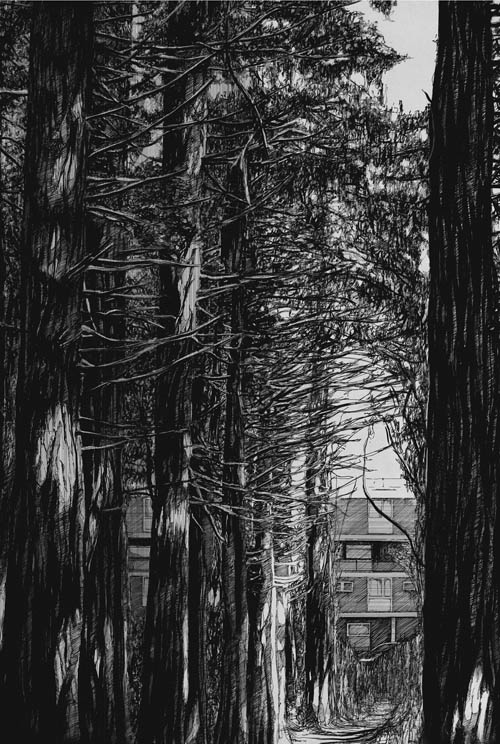

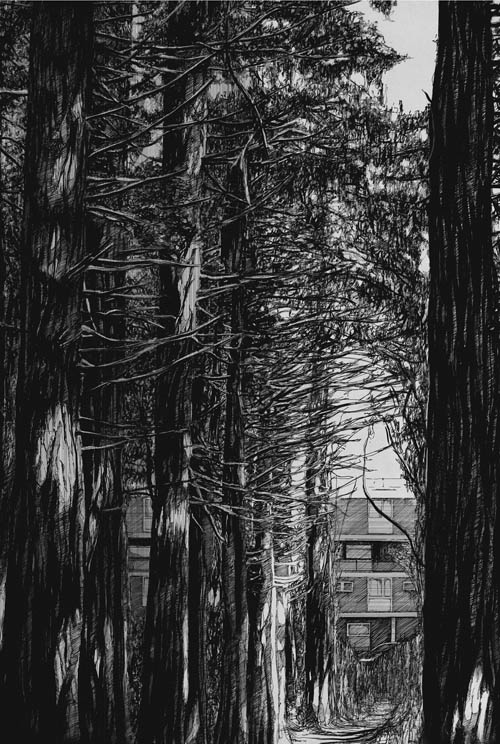

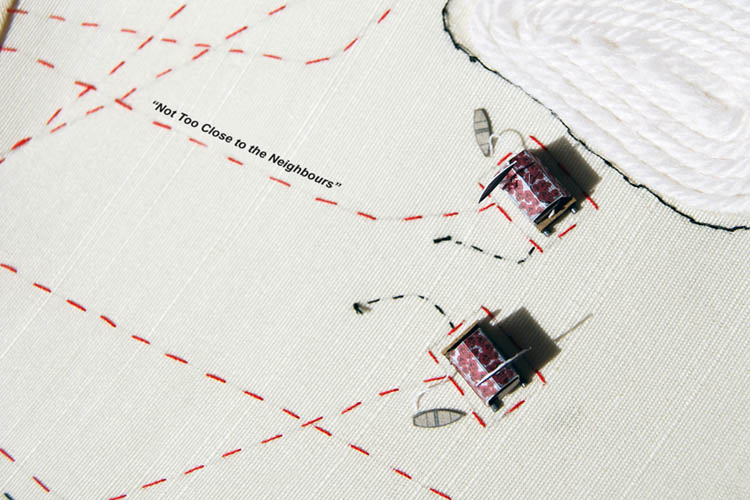

[Image: “The Dormant Workshop” by Tom Noonan, courtesy of the architect].

[Image: “The Dormant Workshop” by Tom Noonan, courtesy of the architect].

While studying at the Bartlett School of Architecture in London, recent graduate Tom Noonan produced a series of variably-sized hand-drawings to illustrate a fictional reforestation of the Thames estuary.

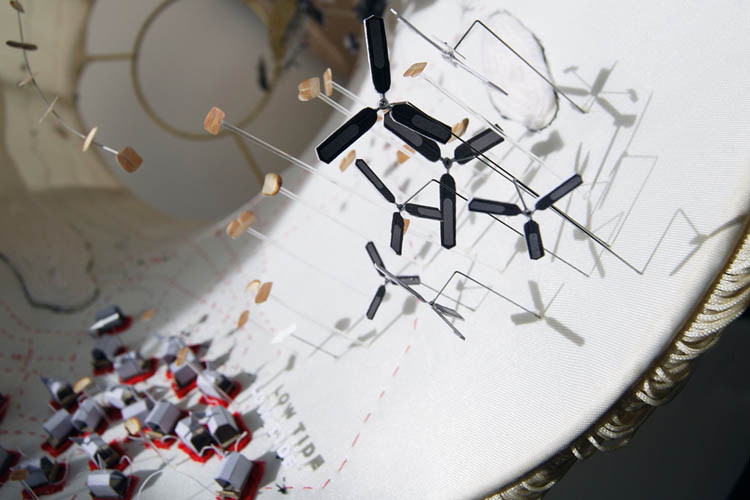

[Image: “Log Harvest 2041” by Tom Noonan, courtesy of the architect].

[Image: “Log Harvest 2041” by Tom Noonan, courtesy of the architect].

Stewarding, but also openly capitalizing on, this return of woodsy nature is the John Evelyn Institute of Arboreal Science, an imaginary trade organization (of which we will read more, below).

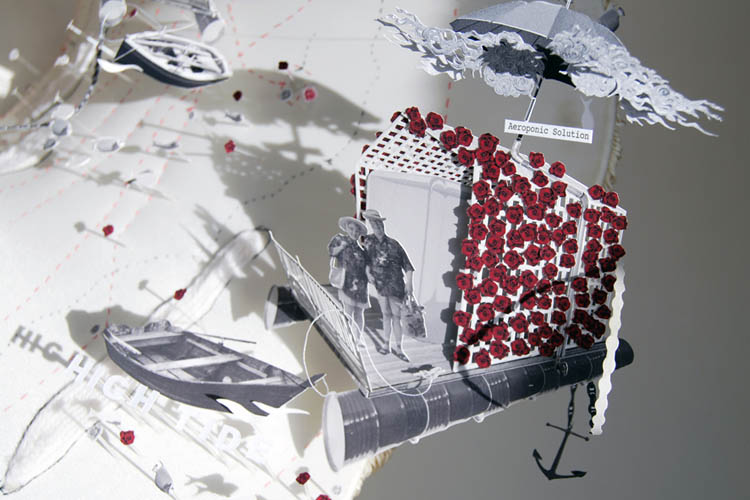

[Image: “Reforestation of the Thames Estuary” by Tom Noonan, courtesy of the architect].

[Image: “Reforestation of the Thames Estuary” by Tom Noonan, courtesy of the architect].

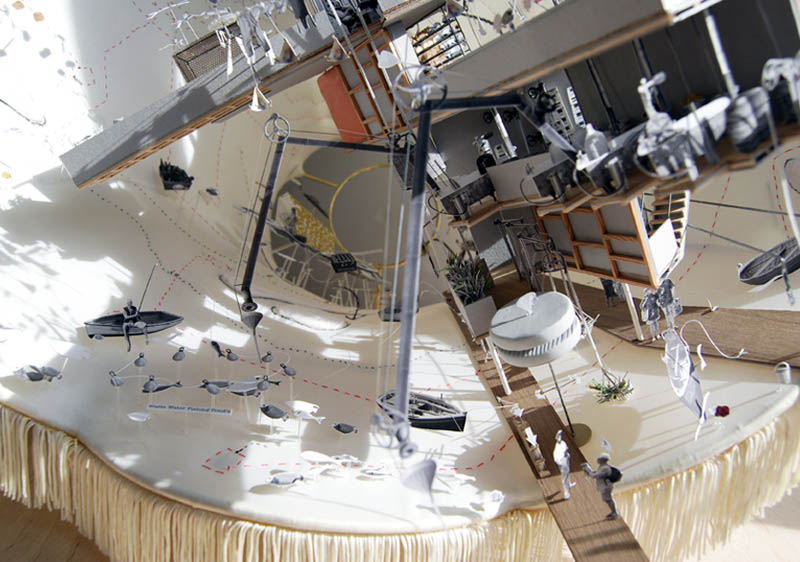

The urban scenario thus outlined—imagining a “future timber and plantation industry” stretching “throughout London, and beyond”—is like something out of Roger Deakin’s extraordinary book Wildwood: A Journey Through Trees (previously described here) or even After London by Richard Jeffreys.

In that latter book, Jeffreys describes a thoroughly post-human London, as the ruined city is reconquered by forests, mudflats, aquatic grasses, and wild animals: “From an elevation, therefore,” Jeffreys writes, “there was nothing visible but endless forest and marsh. On the level ground and plains the view was limited to a short distance, because of the thickets and the saplings which had now become young trees… By degrees the trees of the vale seemed as it were to invade and march up the hills, and, as we see in our time, in many places the downs are hidden altogether with a stunted kind of forest.”

Noonan, in a clearly more domesticated sense—and it would have been interesting to see a more ambitious reforestation of all of southeast England in these images—has illustrated an economically useful version of Jeffreys’s eco-prophetic tale.

[Image: “Lecture Preparations” by Tom Noonan, courtesy of the architect].

[Image: “Lecture Preparations” by Tom Noonan, courtesy of the architect].

From Noonan’s own project description:

The reforestation of the Thames Estuary sees the transformation of a city and its environment, in a future where timber is to become the City’s main building resource. Forests and plantations established around the Thames Estuary provide the source for the world’s only truly renewable building material. The river Thames once again becomes a working river, transporting timber throughout the city.

It is within these economic circumstances that the John Evelyn Institute of Arboreal Science can establish itself, Noonan suggests:

The John Evelyn Institute of Arboreal Scienc eat Deptford is the hub of this new industry. It is a centre for the development and promotion of the use of timber in the construction of London’s future architecture. Its primary aim is to reintroduce wood as a prominent material in construction. Through research, exploration and experimentation the Institute attempts to raise the visibility of wood for architects, engineers, the rest of the construction industry and public alike. Alongside programmes of education and learning, the landscape of the Institute houses the infrastructure required for the timber industry.

They are similar to an organization like a cross between TRADA and the Wooodland Trust, say.

[Image: “Urban Nature” by Tom Noonan, courtesy of the architect].

[Image: “Urban Nature” by Tom Noonan, courtesy of the architect].

And the Institute requires, of course, its own architectural HQ.

[Image: “Timber Craft Workshop” by Tom Noonan, courtesy of the architect].

[Image: “Timber Craft Workshop” by Tom Noonan, courtesy of the architect].

Noonan provides that, as well. He describes the Institute as “a landscape connecting Deptford with the river,” not quite a building at all. It is an “architecture that does not conform to the urban timeframe. Rather, its form and occupation is dependent on the cycles of nature.”

The architecture is created slowly—its first years devoid of great activity, as plantations mature. The undercroft of the landscape is used for education and administration. The landscape above becomes an extension of the river bank, returning the privatised spaces of the Thames to the public realm. Gaps and cuts into the landscape offer glimpses into the monumental storage halls and workshops below, which eagerly anticipate the first log harvest. 2041 sees the arrival of the first harvest. The landscape and river burst in a flurry of theatrical activity, reminiscent of centuries before. As the plantations grow and spread, new architectures, infrastructures and environments arise throughout London and the banks of the Thames, and beyond.

The drawings are extraordinary, and worth exploring in more detail, and—while Noonan’s vision of London transformed into a working forest plantation would have benefitted from some additional documentation, such as maps*—it is a delirious one.

[Image: “Thames Revival” by Tom Noonan, courtesy of the architect].

[Image: “Thames Revival” by Tom Noonan, courtesy of the architect].

Considering the ongoing overdose of urban agriculture imagery passing through the architecture world these days, it is refreshing simply to see someone hit a slightly different note: to explore urban forestry in an aesthetically powerful way and to envision a world in which the future structural promise of cultivated plantlife comes to shape the city.

*I wrote this without realizing that the package of images sent to me did not include the entire project—which comes complete with maps.

[Image: The lyrics from “Desk Crit” by Crash Cadet].

[Image: The lyrics from “Desk Crit” by Crash Cadet].

[Image: “The Dormant Workshop” by

[Image: “The Dormant Workshop” by  [Image: “Log Harvest 2041” by

[Image: “Log Harvest 2041” by  [Image: “Reforestation of the Thames Estuary” by

[Image: “Reforestation of the Thames Estuary” by  [Image: “Lecture Preparations” by

[Image: “Lecture Preparations” by  [Image: “Urban Nature” by

[Image: “Urban Nature” by  [Image: “Timber Craft Workshop” by

[Image: “Timber Craft Workshop” by  [Image: “Thames Revival” by

[Image: “Thames Revival” by  [Image: Photo courtesy of Andrea Tintori and

[Image: Photo courtesy of Andrea Tintori and  [Image: Photo courtesy of Andrea Tintori and

[Image: Photo courtesy of Andrea Tintori and  [Image: A fenced-off, back alley security stair in Toronto, via

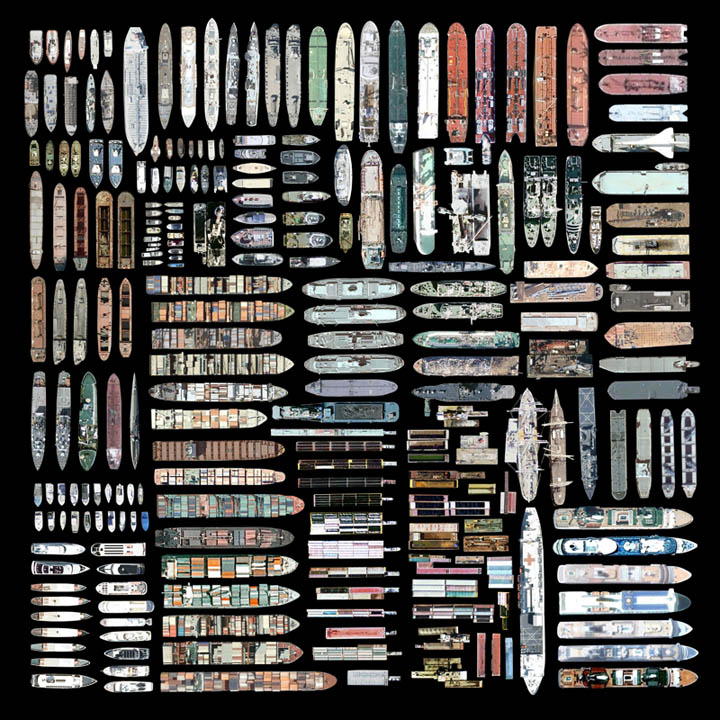

[Image: A fenced-off, back alley security stair in Toronto, via  [Image: Oceangoing ships clipped and stitched from Google Maps by artist

[Image: Oceangoing ships clipped and stitched from Google Maps by artist

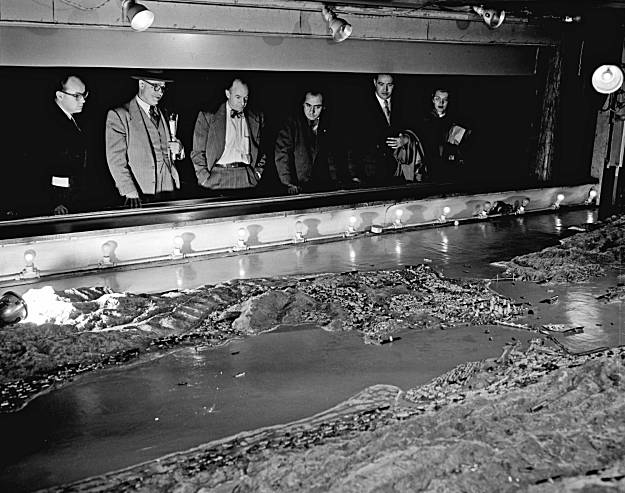

[Image: Photo by Barney Peterson, courtesy of the

[Image: Photo by Barney Peterson, courtesy of the  [Image: Photo by Barney Peterson, courtesy of the

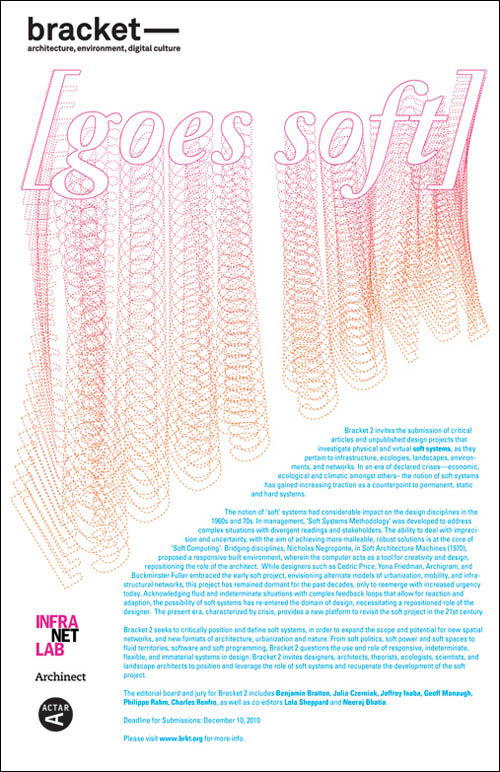

[Image: Photo by Barney Peterson, courtesy of the  Just a quick reminder that you have till December 10 to submit to

Just a quick reminder that you have till December 10 to submit to

[Image: A toy antique oscilloscope by Andrew Smith, courtesy of

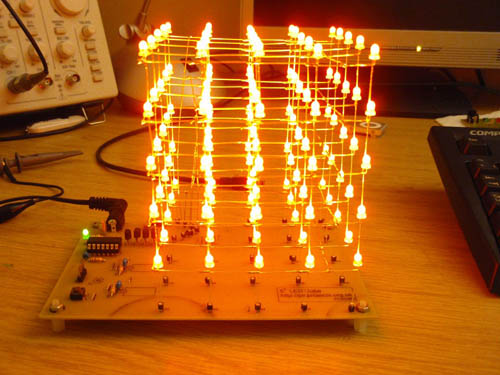

[Image: A toy antique oscilloscope by Andrew Smith, courtesy of  [Image: An LED cube by

[Image: An LED cube by  [Image: “GPS pigeons” by

[Image: “GPS pigeons” by

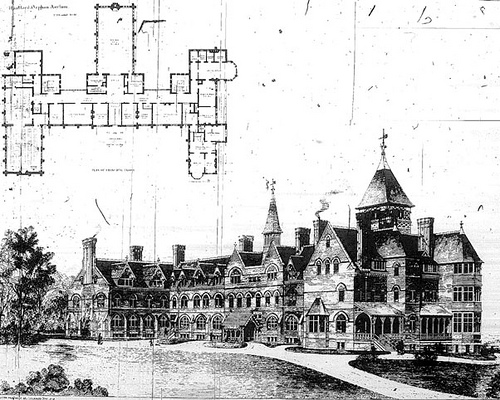

[Image: An old asylum and its floorplan, courtesy of the

[Image: An old asylum and its floorplan, courtesy of the

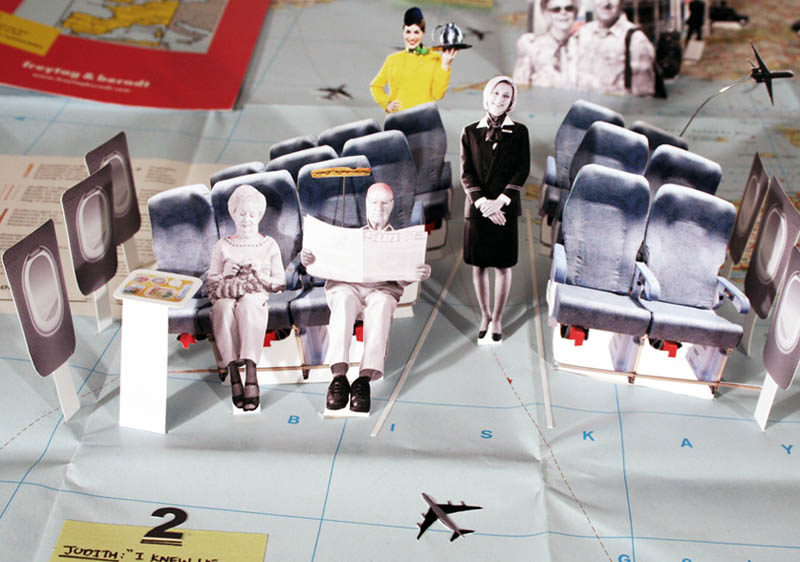

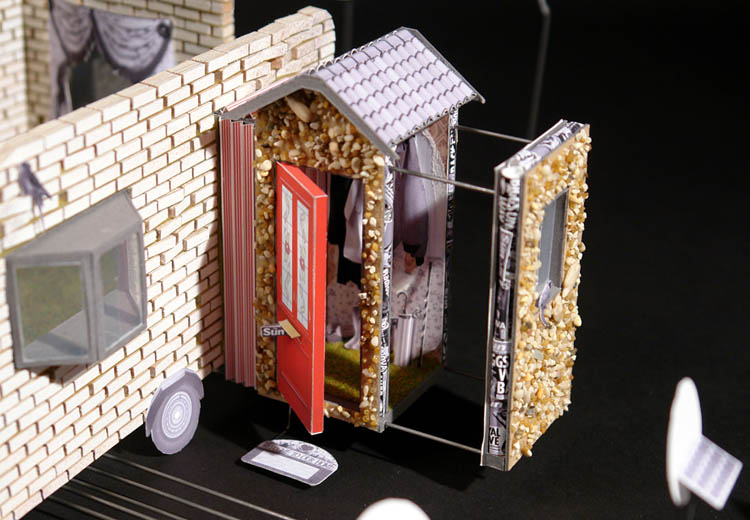

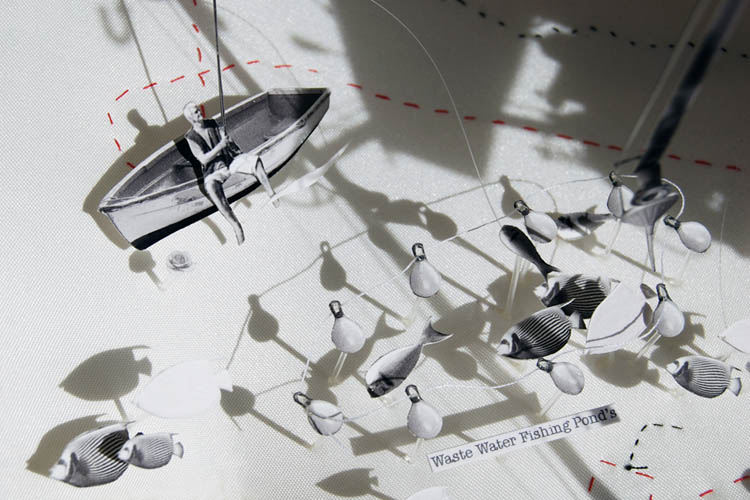

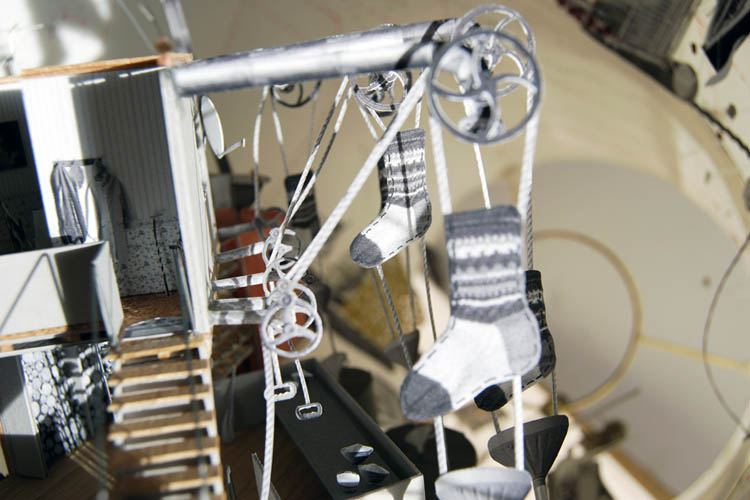

[Image: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Image: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by  [Image: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Image: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by