[Image: The Castle House tower by Hamiltons architects; via Inhabitat].

[Image: The Castle House tower by Hamiltons architects; via Inhabitat].

Unless a “green” building actively remediates its local environment – for instance, scrubbing toxins from the air or absorbing carbon dioxide – that building is not “good” for the environment. It’s simply not as bad as it could have been.

Buildings aren’t (yet) like huge Brita filters that you can install in a city somewhere and thus deliver pure water, cleaner air, better topsoil, or increased biodiversity to the local population.

I hope buildings will do all of that someday – and some architects are already proposing such structures – but, for the most part, today’s “green” buildings are simply not as bad as they could have been.

A high-rise that off-sets some of its power use through the installation of rooftop wind turbines is great: it looks cool, magazine readers go crazy for it, and the building’s future tenants save loads of money on electricity bills. But once you factor in these savings, something like the new Castle House eco-skyscraper still ends up being a net drain on the system.

It’s not good for the environment; it’s just not as bad as it could have been.

[Image: The Castle House tower by Hamiltons architects; via Inhabitat].

[Image: The Castle House tower by Hamiltons architects; via Inhabitat].

My larger point, however, is that you can write about a tower that uses less structural steel, and that tower might be better for the environment than, say, a steel-intensive luxury high-rise with three rooftop wind turbines, but your article probably won’t get 890 Diggs – and so you write about flashy gizmos with huge downsteam maintenance bills, instead.

To use an inappropriately over-simplified example, imagine two identical 60-story high-rises. The architect of Tower A convenes his engineering team one day and they proceed to rearrange some of the building’s internal structural steel; they’re thus able to cut out some cantilevers, for instance, and to eliminate excess building material, more generally. This reduces the structure’s embodied construction energy, by which I mean transport costs, steel manufacture, etc. A few days later, maybe the architect of Tower A even cuts out 10% of the track-lighting, or he makes the office lobbies a tiny bit smaller and, thus, easier to climate-control.

The architect of Tower B makes no such changes – but he does add a wind turbine to the roof.

Architect A has arguably had a much greater impact on his building’s environmental bottom line – but we don’t hear about Architect A.

We hear about Architect B, because wind turbines look great, they are easy to explain, and they don’t require much journalistic research.

Architect B – who has mastered the art of ornamentalizing sustainability – comes off as a hero; Architect A, despite his accomplishments, is overlooked.

Again, my point is simply that relatively unspectacular design decisions can be made in the process of constructing a building that will help lessen that building’s environmental impact – but often these decisions aren’t flashy. They don’t photograph well, and they don’t require cool new pieces of Digg-friendly technology.

And so your building, however not bad it is for the environment, doesn’t receive any free publicity on green building blogs. I’m not pointing fingers, either: this diagnosis is at least as true for BLDGBLOG.

A relatively lame example here is Tudor residential architecture: as I mentioned back in November, Tudor-style houses are remarkably energy efficient. “Wind turbines, solar panels and other hi-tech green devices might get the media attention,” I quote in that earlier post, “but the smartest way to save energy may be to live in a Tudor house and insulate the attic and repair the windows.”

[Image: Little Moreton Hall, “an early model of energy efficiency,” according to the Guardian Weekly].

[Image: Little Moreton Hall, “an early model of energy efficiency,” according to the Guardian Weekly].

In any case, I just think it’s worth pointing out that you can compare a new building to the environmental impact of no building at all – in which case you have quite a high bar to clear before your new building is truly “green” – or you can compare that new building to how bad it might otherwise have been.

If you’re only doing the latter, then almost literally any minor design decision – including ornamental wind turbines or a few arbitrary solar panels – will make that building “green.” In the process, “green building” slowly loses any rigor or integrity it might previously have had.

Wind turbines, solar panels, rainwater catchment systems, etc., are totally awesome – I unironically endorse their architectural use – but they don’t make a building good for the environment. Or at least they don’t yet.

They just make that building less bad for the environment than it would have been without them.

Which is still great – but we shouldn’t mistake restraint for generosity.

In other words, we shouldn’t pretend that a steel-intensive high-rise with a few wind turbines on top is somehow good for us; it’s just not as bad as it could have been.

I would hope that at least long-term readers know that this blog is “pro-sustainability” – I’ll even sheepishly point out my own interview with Ed Mazria – but I think it’s extremely important to realize that you may be building less bad high-rises, but you are still building high-rises. I remain radically unconvinced that a “green” skyscraper is better than no skyscraper at all – and yet green skyscraper enthusiasts are out high-fiving each other as if their own positive energy is enough to counteract carbon emissions from the global steel industry.

This is actually one of the reasons why I like Ed Mazria and his Architecture 2030 organization so much.

In a recent press release, Architecture 2030 pointed out that “the CO2 emissions from only one medium-sized (500 MW) coal-fired power plant” are enough to negate the effects of planting 300,000 trees in only ten days, among other amazing statistics – including the fact that the entire Architecture 2030 effort, as applied to building renovations, would be negated by the “CO2 emissions from just one 750 MW coal-fired power plant each year” from now till 2030.

If we want to be “green,” Mazria’s press release implies, then a far more effective route toward that goal is to change the coal industry – not to become a luxury high-rise developer in Miami’s South Beach (or, worse, in Dubai).

[Image: The Lighthouse, in Dubai; via Treehugger].

[Image: The Lighthouse, in Dubai; via Treehugger].

Being not as bad as you could have been is not a viable future goal for sustainable architecture.

Build something that genuinely improves the environment – build something that has a measurably negative carbon footprint, for instance, from the manufacture of its steel to the billing of its electricity – and then I’ll be as excited as you are about how “green” the project really is.

Until then, people who are only guilty of screwing the environment over partially win huge accolades: thank you, we say, for only mugging two people last night – I thought you were going to mug three…

Which is positive reinforcement, sure – but it’s not necessarily good for the state of architectural sustainability.

(I apprehensively want to make clear that this post may have been motivated by a post at Inhabitat, but it is in no way meant as an attack on that site; I’ve linked to, hosted an event with, and even written several posts for Inhabitat. I also want to make clear that I am 100% behind so-called green building practices; I just don’t think a “green” building should be mistaken for an environmental improvement; otherwise it’s like mistaking fat-free pound cake for health food: deluded by the packaging, you eat tons of the stuff and you end up like Dom DeLuise).

[Images: Rosslyn Chapel, container of symphonies].

[Images: Rosslyn Chapel, container of symphonies]. [Image: The intricate ceilingry of Rosslyn Chapel, photographed by

[Image: The intricate ceilingry of Rosslyn Chapel, photographed by  [Image: The Rosslyn Chapel doorway, photographed by

[Image: The Rosslyn Chapel doorway, photographed by  [Image: A spectator gazes out at the wave that will destroy him; via

[Image: A spectator gazes out at the wave that will destroy him; via  [Image: Center for Biodiversity by Tecla, part of the

[Image: Center for Biodiversity by Tecla, part of the  [Image: A parking garage and “river remodelling” structure by Labics, part of the

[Image: A parking garage and “river remodelling” structure by Labics, part of the  [Image: The Center for Biodiversity by Tecla, via the

[Image: The Center for Biodiversity by Tecla, via the

[Images: The Waterfall Home by Nemesi, via the

[Images: The Waterfall Home by Nemesi, via the  [Image: A “Hydraulics Museum & Panoramic Bar” by Sudarch, part of the

[Image: A “Hydraulics Museum & Panoramic Bar” by Sudarch, part of the  [Images: A topographical view of the Valle dei Mulini, via the

[Images: A topographical view of the Valle dei Mulini, via the  What made the night particularly memorable, however, was that I had to park several blocks away – and so, to get back to my car in the darkness, the sun having set on Los Angeles, I found myself walking past the

What made the night particularly memorable, however, was that I had to park several blocks away – and so, to get back to my car in the darkness, the sun having set on Los Angeles, I found myself walking past the  So we’ll be talking, I assume, about things like cities and writing and architecture, but also about war and music and climate change, by way of science, Athanasius Kircher, contemporary politics, and – of course – Weschler’s brand-new-in-paperback book

So we’ll be talking, I assume, about things like cities and writing and architecture, but also about war and music and climate change, by way of science, Athanasius Kircher, contemporary politics, and – of course – Weschler’s brand-new-in-paperback book  We’re still (always!) looking for

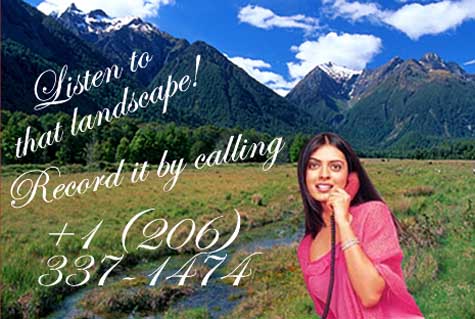

We’re still (always!) looking for  The basic idea, if you’re curious, is to open up the artistic possibilities of field recordings to anyone with a telephone – whether that’s a mobile phone, a public phone, or even a phone attached to the wall in your kitchen.

The basic idea, if you’re curious, is to open up the artistic possibilities of field recordings to anyone with a telephone – whether that’s a mobile phone, a public phone, or even a phone attached to the wall in your kitchen.  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  From the artist’s website:

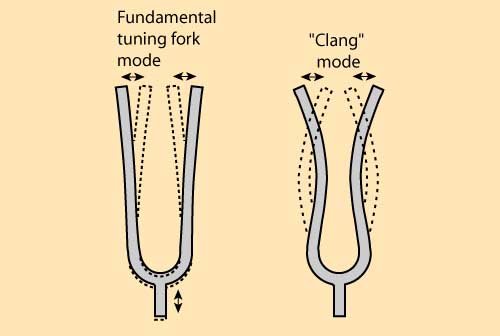

From the artist’s website: The basic trouble, the article says, is that we haven’t sent microphones to many of the places we know so well visually.

The basic trouble, the article says, is that we haven’t sent microphones to many of the places we know so well visually.  [Image: The canyonlands of Mars; courtesy of NASA].

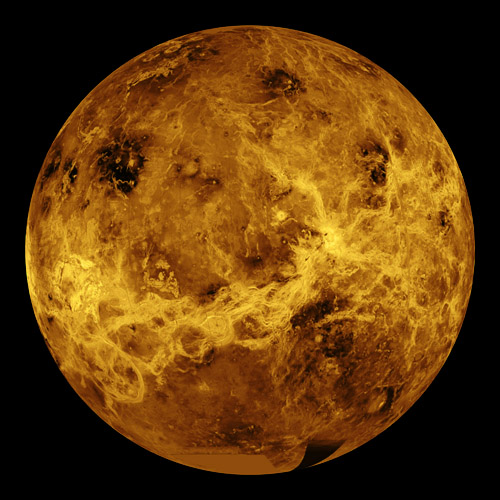

[Image: The canyonlands of Mars; courtesy of NASA]. [Image: A stunning view of Venus, which looks more solar than planetary; courtesy of NASA].

[Image: A stunning view of Venus, which looks more solar than planetary; courtesy of NASA]. [Image: The Earth’s moon].

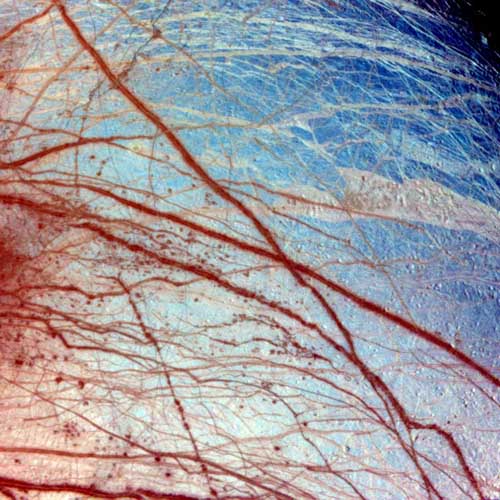

[Image: The Earth’s moon]. [Image: The cracked icy surface of Europa].

[Image: The cracked icy surface of Europa]. [Note: This post was originally written for

[Note: This post was originally written for  Of course, this would not be the first time someone has suggested that cities have a certain sound, unique to them, or that cities should learn to cultivate their unique sonic qualities.

Of course, this would not be the first time someone has suggested that cities have a certain sound, unique to them, or that cities should learn to cultivate their unique sonic qualities.  In his 1964 novel

In his 1964 novel