Andrew Maynard‘s Holl House starts off as a vertical column, then unlocks into a horizontal network of hinged structures –

– in a process described by this diagram:

Sure, there could be loads and loads of stress fracture problems, pinched fingers and drunken accidents – the whole damn thing folding up as you hit the wrong button, collapsing into bed – but put several of these things together and you’ve either got the most exciting micro-city in the world, or an Oscar-winning set for a new science fiction film. Or both.

If I were rich, I’d buy fourteen of them.

But meanwhile, the designer, Andrew Maynard, appears to have no shortage of great ideas. I only today got around to reading a whole profile of his work posted on Archinect last month, and I was practically laughing out loud some of it’s so good.

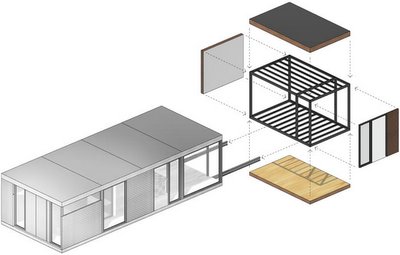

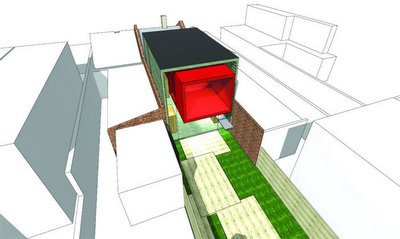

Check out his prefab entry to the 2004 VicUrban affordable housing competition.

“How can the housing industry make exciting, well designed and cheap housing?” Maynard asks. “Easy, mimic the car industry.”

“The dimensions of the basic module are dictated by the maximum dimensions available to be transported legally on Australian roads without permits.”

The house is then assembled on-site –

– where “work is minimised to the installation of a steel ‘train track’ footing system allowing the prefabricated modules to simply be slid into place. The prefabricated module is based on a rigid galvanised steel frame with plasterboard internal finish and stained farmed pine external skin.”

Soon you could have an entire community: “Alternating between single storey and double storey allows estates to have a visual diversity based on a single modular form. The flat bituminous roof also allows rooves to easily become trafficable outdoor areas for second storey spaces.”

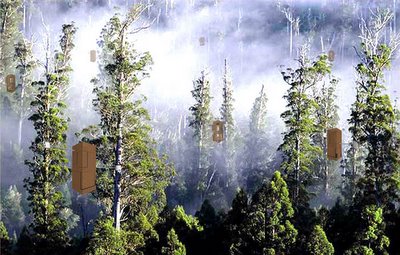

Then there’s Maynard’s Styx Valley Protest Structure, which was designed to assist anti-logging protests in Tasmania’s Styx Valley Forest.

As Maynard writes: “The Styx Valley Forest is a pristine wilderness in south western Tasmania. It is home to the tallest hardwood trees in the world averaging over 80 metres… Many of the trees are over 400 years old… Unfortunately the Styx Valley falls just outside [Tasmania’s] South West National Park and it is now under attack from logging companies.”

How does the Protest Structure work? “Rather than inserting the structure into the canopy of a single tree, the structure is designed to attach itself to three trees,” so that only “a small number of structures can secure the well being of a large area of pristine wilderness.”

I would think, however, that even without this ostensibly protective purpose, such structures would be amazing places to spend time. Somewhere between Swiss Family Robinson and Return of the Jedi, they could serve as little writing labs, up in the trees, or just places where you can clear your mind and breathe.

Again, BLDGBLOG would buy fourteen of them if it could.

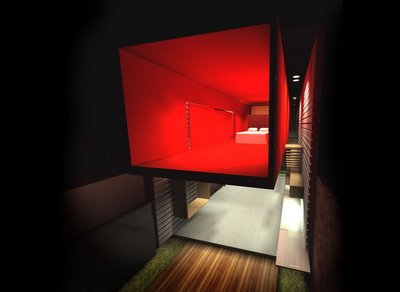

Somewhere between furniture and inhabitable architecture, there are some really great ideas on Maynard’s site; check out the Design Pod, the 2nd Sproule House, the Conceptual Library for Japan and the Cog House for starters.

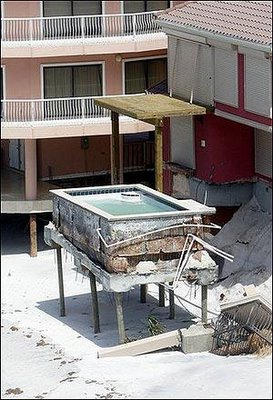

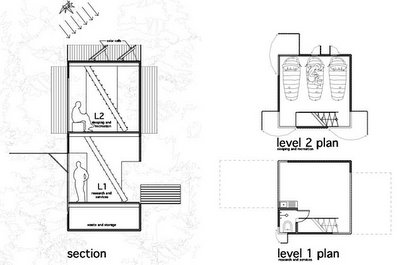

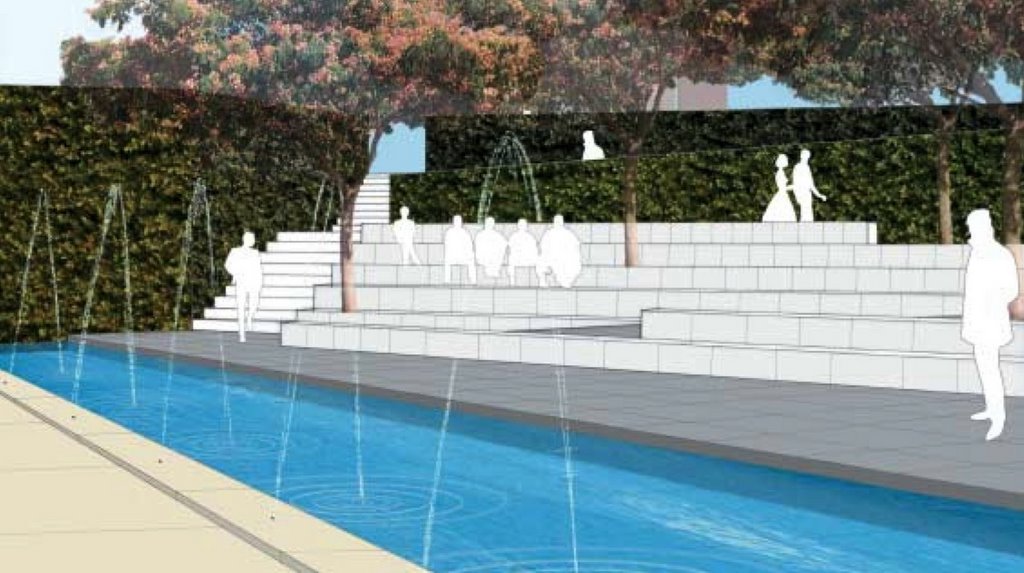

Here are some images of the 2nd Sproule House – but check out the site for more:

(For some other cool and prefabulous structures, see BLDGBLOG’s own Garage conversions, and Inhabitat’s frequently updated prefab database).

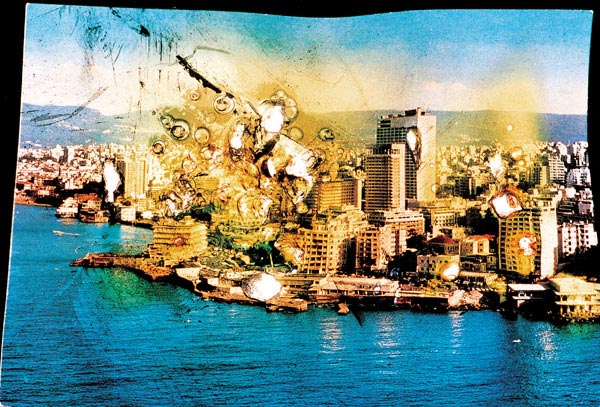

[Image: From Wonder Beirut, 1997-2004, by Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige].

[Image: From Wonder Beirut, 1997-2004, by Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige].

[Image: By

[Image: By

[Images: By

[Images: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: Bernard Khoury,

[Image: Bernard Khoury,  [Image: Bernard Khoury,

[Image: Bernard Khoury,