[Image: Trevor Paglen, “PAN (Unknown; USA-207),” from The Other Night Sky].

[Image: Trevor Paglen, “PAN (Unknown; USA-207),” from The Other Night Sky].

I had the pleasure last winter of attending a lecture by Trevor Paglen in Amsterdam, where he spoke about a project of his called The Last Pictures. As Paglen describes it, “Humanity’s longest lasting remnants are found among the stars.”

Over the last fifty years, hundreds of satellites have been launched into geosynchronous orbits, forming a ring of machines 36,000 kilometers from earth. Thousands of times further away than most other satellites, geostationary spacecraft remain locked as man-made moons in perpetual orbit long after their operational lifetimes. Geosynchronous spacecraft will be among civilization’s most enduring remnants, quietly circling earth until the earth is no more.

Paglen ended his lecture with an amazing anecdote worth repeating here. Expanding on this notion—that humanity’s longest-lasting ruins will not be cities, cathedrals, or even mines, but rather geostationary satellites orbiting the Earth, surviving for literally billions of years beyond anything we might build on the planet’s surface—Paglen tried to conjure up what this could look like for other species in the far future.

Billions of years from now, he began to narrate, long after city lights and the humans who made them have disappeared from the Earth, other intelligent species might eventually begin to see traces of humanity’s long-since erased presence on the planet.

Consider deep-sea squid, Paglen suggested, who would have billions of years to continue developing and perfecting their incredible eyesight, a sensory skill perfect for peering through the otherwise impenetrable darkness of the oceans—yet also an eyesight that could let them gaze out at the stars in deep space.

Perhaps, Paglen speculated, these future deep-sea squid with their extraordinary powers of sight honed precisely for focusing on tiny points of light in the darkness might drift up to the surface of the ocean on calm nights to look upward at the stars, viewing a scene that will have rearranged into whole new constellations since the last time humans walked the Earth.

And, there, the squid might notice something.

High above, seeming to move against the tides of distant planets and stars, would be tiny reflective points that never stray from their locations. They are there every night; they are more eternal than even the largest and most impressive constellations in the sky sliding nightly around them.

Seeming to look back at the squid like the eyes of patient gods, permanent and unchanging in these places reserved for them there in the firmament, those points would be nothing other than the geostationary satellites Paglen made reference to.

This would be the only real evidence, he suggested, to any terrestrial lifeforms in the distant future that humans had ever existed: strange ruins stuck there in the night, passively reflecting the sun, never falling, angelic and undisturbed, peering back through the veil of stars.

[Image: Star trails, seen from space, via Wikimedia].

[Image: Star trails, seen from space, via Wikimedia].

Aside from the awesome, Lovecraftian poetry of this image—of tentacular creatures emerging from the benthic deep to gaze upward with eyes the size of automobiles at satellites far older than even continents and mountain ranges—the actual moment of seeing these machines for ourselves is equally shocking.

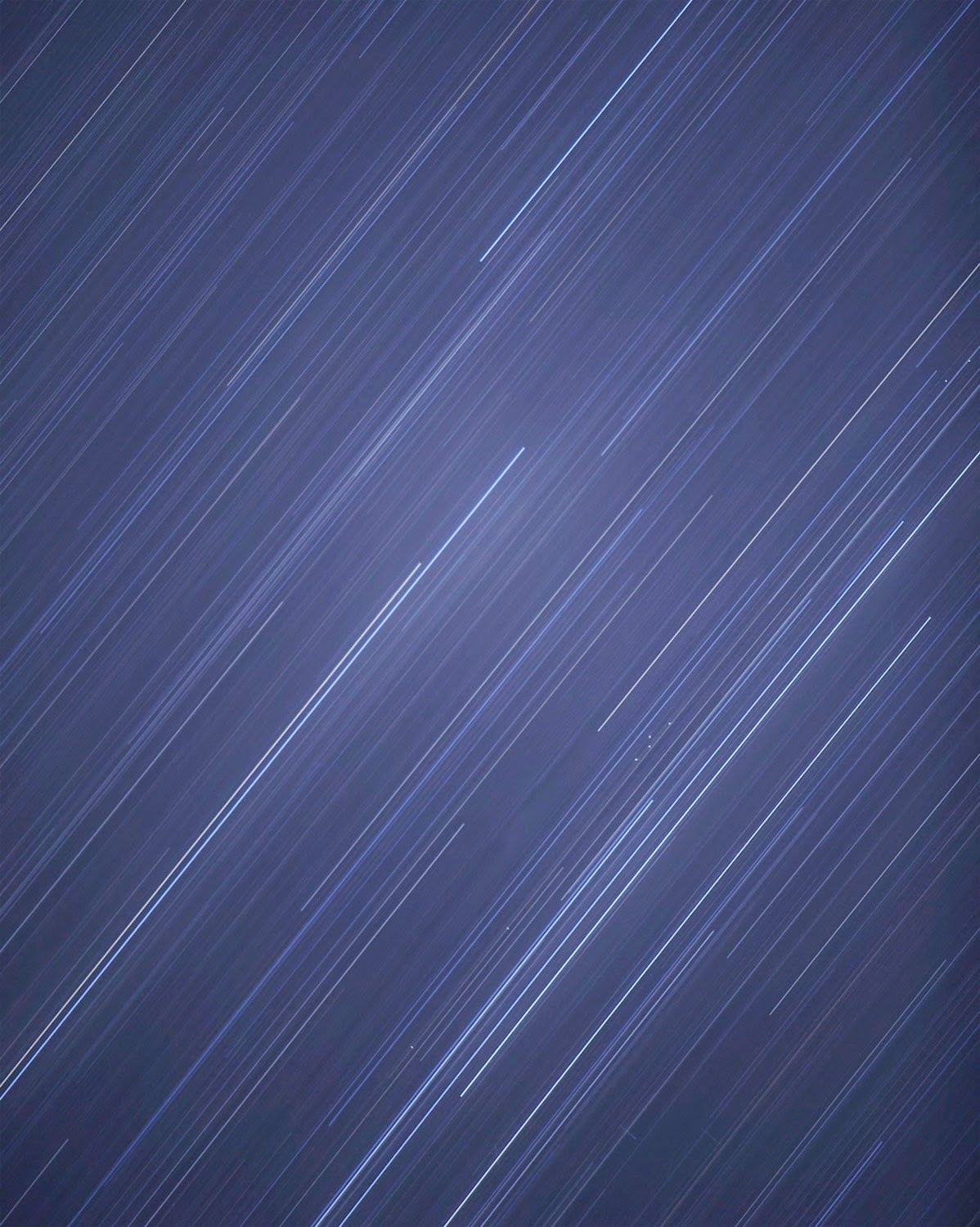

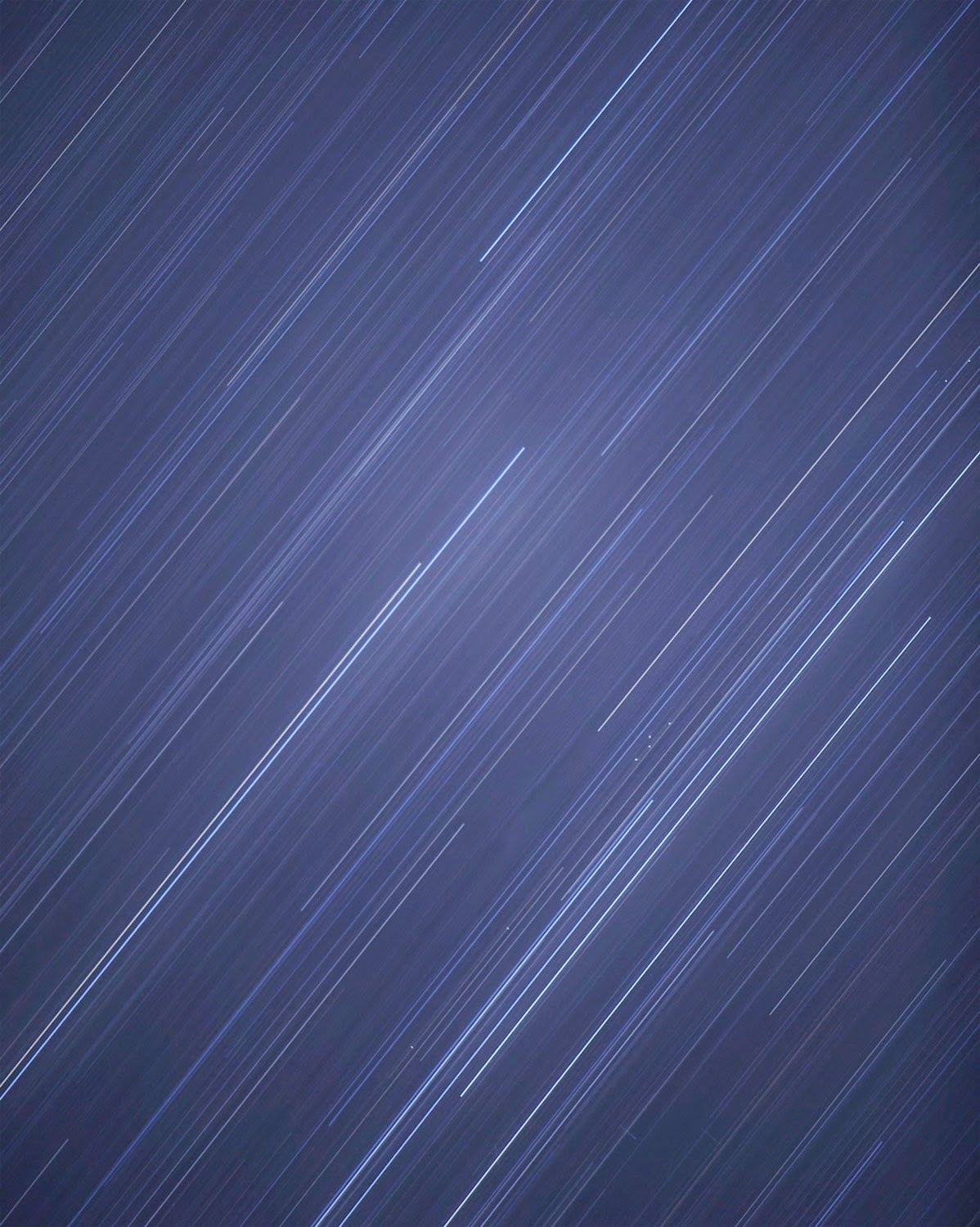

By now, for example, we have all seen so-called “star trail” photos, where the Earth’s rotation stretches every point of starlight into long, perfect curves through the night sky. These are gorgeous, if somewhat clichéd, images, and they tend to evoke an almost psychedelic state of cosmic wonder, very nearly the opposite of anything sinister or disturbing.

[Image: More star trails from space, via Wikipedia].

[Image: More star trails from space, via Wikipedia].

Yet in Paglen’s photo “PAN (Unknown; USA-207)”—part of another project of his called The Other Night Sky— something incredible and haunting occurs.

Amidst all those moving stars blurred across the sky like ribbons, tiny points of reflected light burn through—and they are not moving at all. There is something else up there, this image makes clear, something utterly, unnaturally still, something frozen there amidst the whirl of space, looking back down at us as if through cracks between the stars.

[Image: Cropping in to highlight the geostationary satellites—the unblurred dots between the star trails—in “PAN (Unknown; USA-207)” by Trevor Paglen, from The Other Night Sky].

[Image: Cropping in to highlight the geostationary satellites—the unblurred dots between the star trails—in “PAN (Unknown; USA-207)” by Trevor Paglen, from The Other Night Sky].

The Other Night Sky, Paglen explains, “is a project to track and photograph classified American satellites, space debris, and other obscure objects in Earth orbit.”

To do so, he uses “observational data produced by an international network of amateur satellite observers to calculate the position and timing of overhead transits which are photographed with telescopes and large-format cameras and other imaging devices.”

The image that opens this post “depicts an array of spacecraft in geostationary orbit at 34.5 degrees east, a position over central Kenya. In the lower right of the image is a cluster of four spacecraft. The second from the left is known as ‘PAN.'”

What is PAN? Well, the interesting thing is that not many people actually know. Its initials stand for “Palladium At Night,” but “this is one mysterious bird,” satellite watchers have claimed; it is a “mystery satellite” with “an unusual history of frequent relocations,” although it is to be found in the eastern hemisphere, stationed far above the Indian Ocean (Paglen took this photograph from South Africa).

As Paglen writes, “PAN is unique among classified American satellites because it is not publically claimed by any intelligence of military agency. Space analysts have speculated that PAN may be operated by the Central Intelligence Agency.” Paglen and others have speculated about other possible meanings of the name PAN—check out his website for more on that—but what strikes me here is less the political backstory behind the satellites than the visceral effect such an otherwise abstract photograph can have.

In other words, we don’t actually need Paglen’s deep-sea squid of the far future with their extraordinary eyesight to make the point for us that there are now uncanny constellations around the earth, sinister patterns visible against the backdrop of natural motion that weaves the sky into such an inspiring sight.

These fixed points peer back at us through the cracks, an unnatural astronomy installed there in secret by someone or something capable of resisting the normal movements of the universe, never announcing themselves while watching anonymously from space.

[Image: Cropping further into “PAN (Unknown; USA-207)” by Trevor Paglen, from The Other Night Sky].

[Image: Cropping further into “PAN (Unknown; USA-207)” by Trevor Paglen, from The Other Night Sky].

For more on Trevor Paglen’s work, including both The Last Pictures and The Other Night Sky, check out his website.

[Image: From a PDF by Dresser Rand].

[Image: From a PDF by Dresser Rand].

[Image: Untitled (Uranium tailings); Mexican Hat, UT, 2005, by Victoria Sambunaris, from

[Image: Untitled (Uranium tailings); Mexican Hat, UT, 2005, by Victoria Sambunaris, from  [Image: Untitled (talc mine benches); Cameron, MT, 2009, by Victoria Sambunaris, from

[Image: Untitled (talc mine benches); Cameron, MT, 2009, by Victoria Sambunaris, from  [Image: Untitled (Houses); Wendover, UT, 2007, by Victoria Sambunaris, from

[Image: Untitled (Houses); Wendover, UT, 2007, by Victoria Sambunaris, from

[Image: “The Polygon Nuclear Test Site 1 (After the Event),” Kazakhstan (2011); photo by

[Image: “The Polygon Nuclear Test Site 1 (After the Event),” Kazakhstan (2011); photo by  [Image: “The Polygon Nuclear Test Site VII,” Kazakhstan (2011); photo by

[Image: “The Polygon Nuclear Test Site VII,” Kazakhstan (2011); photo by  [Image: “Priozersk (Military Housing)” Kazakhstan (2011); photo by

[Image: “Priozersk (Military Housing)” Kazakhstan (2011); photo by  [Image: “The Aral Sea I (Officers Housing),” Kazakhstan (2011); photo by

[Image: “The Aral Sea I (Officers Housing),” Kazakhstan (2011); photo by

[Image: A “

[Image: A “

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: “Colour experiment no. 61,” 2014; photo by Jens Ziehe, via

[Image: “Colour experiment no. 61,” 2014; photo by Jens Ziehe, via  [Image: “Colour experiment no. 58,” 2014; photo by Jens Ziehe, via

[Image: “Colour experiment no. 58,” 2014; photo by Jens Ziehe, via  [Image: “Colour experiment no. 60,” 2014; photo by Jens Ziehe, via

[Image: “Colour experiment no. 60,” 2014; photo by Jens Ziehe, via  [Image: Installation view of “

[Image: Installation view of “

[Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

[Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Image: The Broelschool, Kortrijk, Belgium, via

[Image: The Broelschool, Kortrijk, Belgium, via  [Images: Some internal views of the Broelschool, via

[Images: Some internal views of the Broelschool, via  [Image: “

[Image: “

[Image:

[Image:  [Image: Star trails, seen from space, via

[Image: Star trails, seen from space, via  [Image: More star trails from space, via

[Image: More star trails from space, via  [Image: Cropping in to highlight the geostationary satellites—the unblurred dots between the star trails—in “PAN (Unknown; USA-207)” by

[Image: Cropping in to highlight the geostationary satellites—the unblurred dots between the star trails—in “PAN (Unknown; USA-207)” by  [Image: Cropping further into “PAN (Unknown; USA-207)” by

[Image: Cropping further into “PAN (Unknown; USA-207)” by

[Image: From a

[Image: From a  [Image: Photographer uncredited; via the

[Image: Photographer uncredited; via the