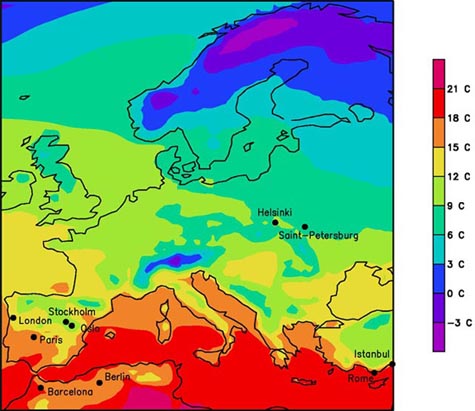

[Image: Future climate map of Europe; the cities have been relocated based on what present locations their future climate will most resemble… or something like that].

[Image: Future climate map of Europe; the cities have been relocated based on what present locations their future climate will most resemble… or something like that].

Last week, the Guardian took a look at what London might look like in 2071. The city, they suggest, will be defined by “heat, dust, and water piped in from Scotland.”

To illustrate the point, that article includes a somewhat cryptic climate map, produced by scientists at the University of Bremen. The map relocates Europe’s capital cities to the present region that most closely resembles their impending future circumstances.

In other words, London, in 2071, will be more like a city on the coast of Portugal today; Paris will feel how central Spain now feels; Berlin, unbelievably, will be like north Africa (one of the coldest summers I’ve ever experienced was in Berlin) – and so on.

These regions are those cities’ “climate analogues.”

In any case, one of the scientists behind the map says that it’s also meant to “help architects and officials who plan buildings, streets and services to adapt to the likely impacts of global warming. ‘If you look at the map you see that Paris moves to the south of Spain. It’s scary that just a few degrees rise will make such a difference. Paris is currently designed to deal with a very different climate, which means designs in future will have to be very different.'”

For exameple: “Houses and buildings in northern Europe typically have windows to the west to make the most of meagre winter sun… ‘But in warmer countries you will never find windows to the west because the sun just pours in all afternoon during the summer.'”

What isn’t mentioned, however, is that architecture will have to change gradually, decade by decade, even year by year; after all, it’d be inappropriate to get rid of all west-facing windows today – and it might still be premature, come 2030 – but, by 2071, perhaps all west-facing windows will be entirely phased out… Or skylights, or rain catchment systems, or winter insulation, or whatever.

But you’ll be able to track changes in the European climate based on what styles of architecture still exist, and where.

Read more at the Guardian.

(Story originally spotted at Kottke).

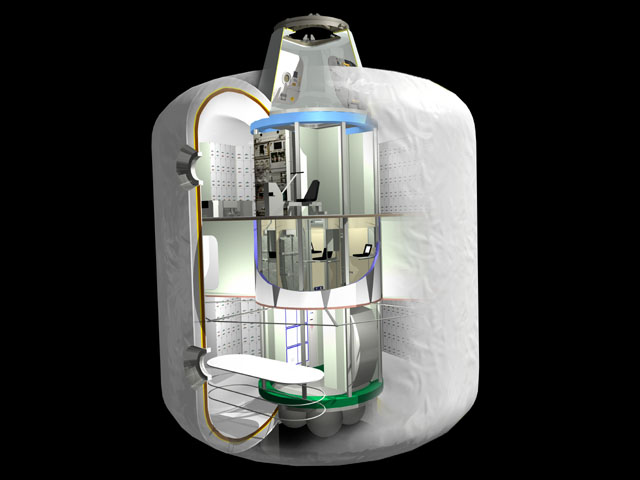

[Image: NASA’s TransHab module, attached to the International Space Station. TransHab designed by Constance Adams; image found via

[Image: NASA’s TransHab module, attached to the International Space Station. TransHab designed by Constance Adams; image found via  [Image: NASA’s TransHab module; image via

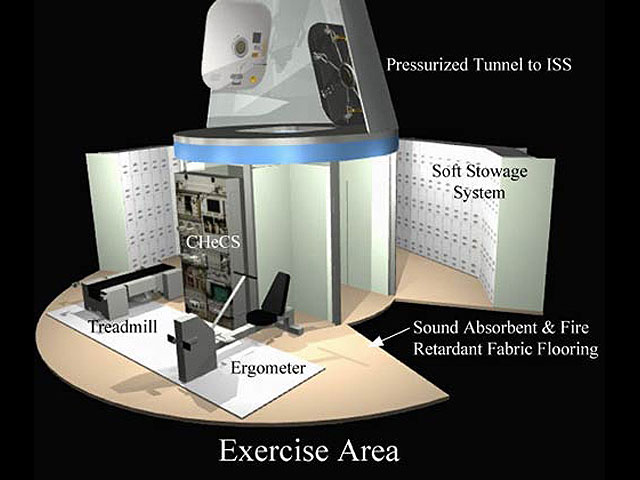

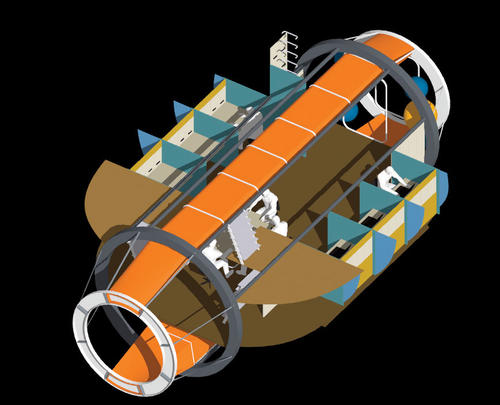

[Image: NASA’s TransHab module; image via  [Image: The TransHab, cut-away to reveal the exercise room and a “pressurized tunnel” no home in space should be without. Image via

[Image: The TransHab, cut-away to reveal the exercise room and a “pressurized tunnel” no home in space should be without. Image via

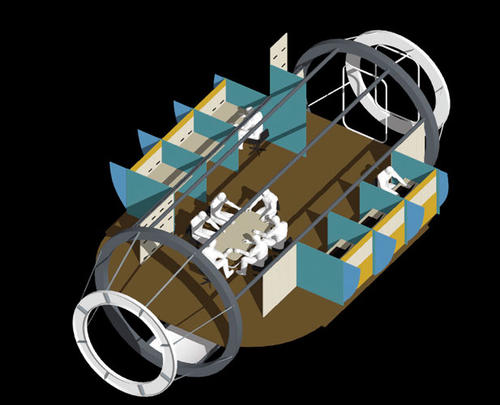

[Images: Georgi Petrov, courtesy of

[Images: Georgi Petrov, courtesy of  [Image: A green Trafalgar, via the

[Image: A green Trafalgar, via the  If you could make your house smell like urine, in other words, all your possessions would be permanently safe…

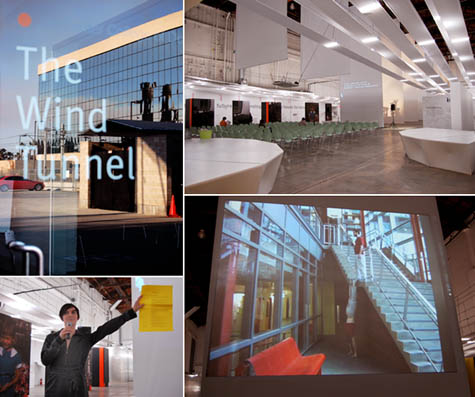

If you could make your house smell like urine, in other words, all your possessions would be permanently safe…  [Image: The final night of the architecture and film festival. From left-right, top-bottom: the

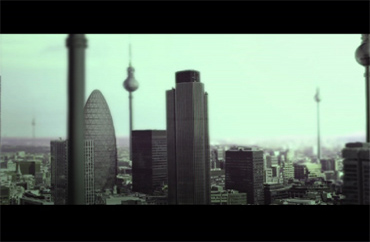

[Image: The final night of the architecture and film festival. From left-right, top-bottom: the  [Image: A scene from Peter Kidger’s The Berlin Infection, produced as part of Kidger’s work with the Bartlett School of Architecture’s

[Image: A scene from Peter Kidger’s The Berlin Infection, produced as part of Kidger’s work with the Bartlett School of Architecture’s  [Image: Outside the wind tunnel – a building rehabbed by

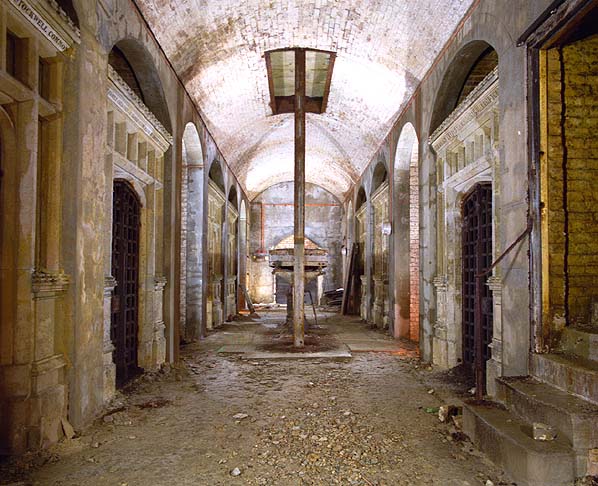

[Image: Outside the wind tunnel – a building rehabbed by  [Image: An underground “coffin lift or ‘catafalque’,” from London’s

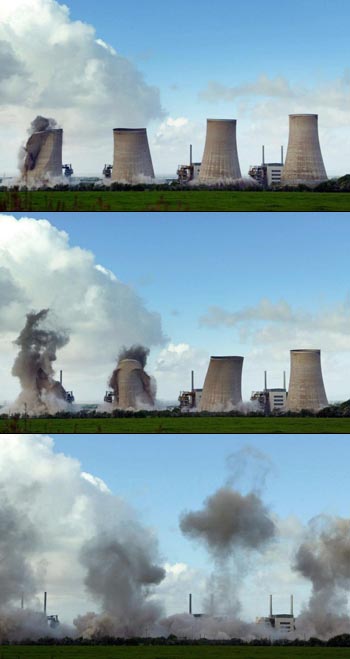

[Image: An underground “coffin lift or ‘catafalque’,” from London’s  [Images: Photos by Neil Burns capture the destruction; via the

[Images: Photos by Neil Burns capture the destruction; via the

[Images: Photos by Andrew Turner and John Smith; via the

[Images: Photos by Andrew Turner and John Smith; via the  [Images: Via

[Images: Via  And so I was thinking today that you could go around Manhattan with a microphone, asking people who have had that dream to describe it, recording all this, live, for the radio – or you ask people who have never had that dream simply to ad lib about what it might be like to discover another room, and you ask them to think about what kind of room they would most like to discover, tucked away inside a closet somewhere in their apartment.

And so I was thinking today that you could go around Manhattan with a microphone, asking people who have had that dream to describe it, recording all this, live, for the radio – or you ask people who have never had that dream simply to ad lib about what it might be like to discover another room, and you ask them to think about what kind of room they would most like to discover, tucked away inside a closet somewhere in their apartment. [Image: From the series

[Image: From the series  [Image: From the series

[Image: From the series  [Image: From the series

[Image: From the series  [Image: From the series

[Image: From the series  According to the BBC, Indian officials have concluded that a “

According to the BBC, Indian officials have concluded that a “