[Image: Walking an “ancient road” in Vermont; photo by Joseph Sywenkyj for The New York Times].

[Image: Walking an “ancient road” in Vermont; photo by Joseph Sywenkyj for The New York Times].

Half-forgotten slashes of land, cutting through, around, and over the hills of Vermont, might actually be “ancient roads,” dating back to colonial times – and a 2006 state law has given the residents of nearby towns a strong incentive for uncovering these buried throughways.

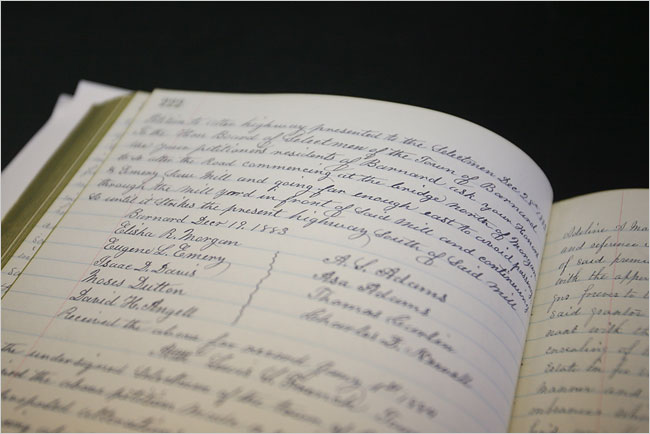

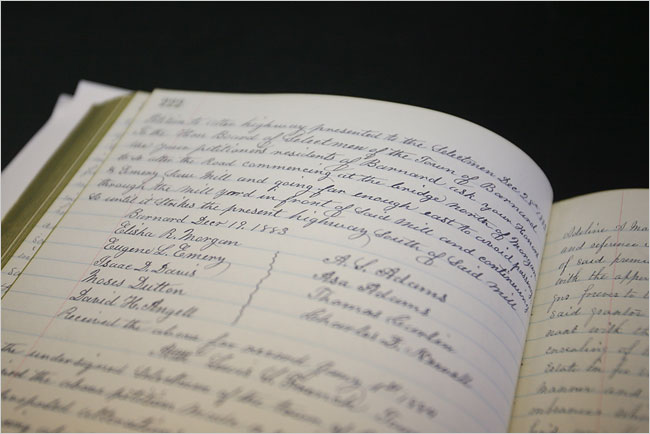

According to The New York Times, “citizen volunteers are poring over record books with a common, increasingly urgent purpose: finding evidence of every road ever legally created in their towns, including many that are now impassable and all but unobservable.” These “elusive roads” – many of them “now all but unrecognizable as byways” – are lost routes, connecting equally erased destinations.

In almost all cases, they’ve barely even left terrestrial traces; in fact, as we’ll see, their presence is almost entirely textual.

If these roads can be re-discovered, however, then they can be added to official town lands. Accordingly:

Some towns, content to abandon the overgrown roads that crisscross their valleys and hills, are forgoing the project. But many more have recruited teams to comb through old documents, make lists of whatever roads they find evidence of, plot them on maps and set out to locate them.

And, in what is surely one of the most interesting geographical subplots in recent newspaper publishing, we read: “Even for history buffs, the challenge is steep: evidence of ancient roads may be scattered through antique record books, incomplete or hard to make sense of.”

Indeed, like something out of the poetry of Paul Metcalf, or even William Carlos Williams, the descriptions found in these old documents are narrative, impressionistic, and vague. They “might be, ‘Starting at Abel Turner’s front door and going to so-and-so’s sawmill,’ said Aaron Worthley, a member of the ancient roads committee in Huntington, southeast of Burlington. ‘But the house might have burned down 100 years ago. And even if not, is the front door still where it was in 1815? These are the kinds of questions we’re dealing with.'”

[Image: A hand-written inventory of Vermont’s ancient routes; photo by Joseph Sywenkyj for The New York Times].

[Image: A hand-written inventory of Vermont’s ancient routes; photo by Joseph Sywenkyj for The New York Times].

While making sense of cryptic references to lost byways is fascinating in and of itself, these acts of perambulatory interpretation are part of a much larger, fairly mundane attempt to end “fights between towns and landowners whose property abuts or even intersects ancient roads.”

In the most infamous legal battle, the town of Chittenden blocked a couple from adding on to their house, saying the addition would encroach on an ancient road laid out in 1793. Town officials forced a showdown when they arrived on the property with chain saws one day in 2004, intending to cut down trees and bushes on the road until the police intervened.

The article refers to one local, a lawyer, who explains that “he loved getting out and looking for hints of ancient roads: parallel stone walls or rows of old-growth trees about 50 feet apart. Old culverts are clues, too, as are cellar holes that suggest people lived there; if so, a road probably passed nearby.”

Think of it as landscape hermeneutics: hunting down traces of a disappeared landscape.

So what would happen, then, if you discovered that an ancient road actually passes through your house – that your living room is a former throughway, and old paths knot and twirl off to every side, one leading right through the guest bedroom? And then another road pops up, and another – and you realize that you live on the intersecting scars of a lost built environment, some old village that disappeared or was destroyed in some H.P. Lovecraft-like enigmatic disaster.

I’m also curious, though, to see what might happen if such a law was passed in a city like London. In an old but interesting review of London: City of Disappearances, a book edited by Iain Sinclair, we’re told that London “is a city of the forgotten.” It is where anyone “can still disappear without trace.” Indeed, London is a city “built upon lost things”; it “towers above forgotten underground rivers and discarded tunnels. It is built upon old graveyards and burial pits.”

More to the point here, entire streets have disappeared: “Catherine Street, Jewin Street, Golden Place are just three of the vanished thoroughfares named in a litany of sorrowful mysteries,” our reviewer points out. “Other streets have been curtailed. Swallow Street has been swallowed by burgeoning London. Grub Street has been renamed Milton Street.”

So what if someone who liked “getting out and looking for hints of ancient roads” were to set about such a task elsewhere? I’m reminded here of China Miéville’s short story “Reports of Certain Events in London” – a perennial reference on BLDGBLOG – in which “unstable” streets appear and disappear throughout the city. One night they’re there, the next night they’re not.

[Image: An old Roman road in Britain; photo via Historic UK].

[Image: An old Roman road in Britain; photo via Historic UK].

But what to make of entire unstable geographies that flash in and out of county land registers, with distant echoes appearing in the hand-written captions of family albums and in old, yellowing letters between loved ones? Could you re-trace ancient roads based on such sources? What if the county’s land archivist was Borges?

Perhaps it’d be a bit like reconstructing all of postwar Berlin, or Dresden, or Hiroshima, based only on geographical descriptions found in the journals of former residents.

How piece together a whole city from a position of extreme textual remove?

I suppose the answer to that question might be found in Vermont over the next few months, with people jogging up and down hillsides, and in and out of archives, tracking down the specters of an older terrain – territorial marks of a vanished world on top of which they’ve been living all along.

(Of interest, earlier on BLDGBLOG: Ancient Lights and Z).

I’ve been going through old magazines to find articles that I hope to read, re-read, or even incorporate into the final edits of the BLDGBLOG Book – and so tonight I came across the January 2007 issue of Metropolis.

I’ve been going through old magazines to find articles that I hope to read, re-read, or even incorporate into the final edits of the BLDGBLOG Book – and so tonight I came across the January 2007 issue of Metropolis. Tomorrow I’ll be down in San Luis Obispo, helping to judge a competition called

Tomorrow I’ll be down in San Luis Obispo, helping to judge a competition called  [Image: A flying logo, or Flogo].

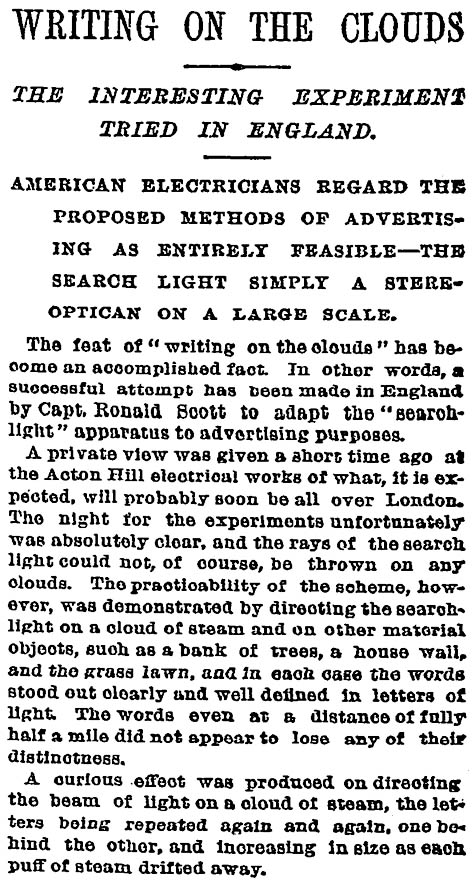

[Image: A flying logo, or Flogo]. [Image: From an article published in 1892 in the New York Times. Read as

[Image: From an article published in 1892 in the New York Times. Read as  1) If you put this into the context of weather control as an emerging technique for urban design – for instance, what we’re seeing in

1) If you put this into the context of weather control as an emerging technique for urban design – for instance, what we’re seeing in  4) Perhaps we all really should give up internet-based blogging and switch instead to the sky. I could buy a small shack on a hill somewhere in Los Angeles and grow a beard. Turning my back on representational form, I’ll emit abstractions of well-made foam into the sky on windy days. Air sculptures, like something by

4) Perhaps we all really should give up internet-based blogging and switch instead to the sky. I could buy a small shack on a hill somewhere in Los Angeles and grow a beard. Turning my back on representational form, I’ll emit abstractions of well-made foam into the sky on windy days. Air sculptures, like something by  [Image: Untitled (2001) by Maurizio Cattelan, courtesy of the Marian Goodman Gallery, via the

[Image: Untitled (2001) by Maurizio Cattelan, courtesy of the Marian Goodman Gallery, via the  [Image: Cairo, photographed by

[Image: Cairo, photographed by  [Image: Cairo, as featured on an old postcard, originally uploaded by Flickr user

[Image: Cairo, as featured on an old postcard, originally uploaded by Flickr user  [Image: Walking an “ancient road” in Vermont; photo by Joseph Sywenkyj for

[Image: Walking an “ancient road” in Vermont; photo by Joseph Sywenkyj for  [Image: A hand-written inventory of Vermont’s ancient routes; photo by Joseph Sywenkyj for

[Image: A hand-written inventory of Vermont’s ancient routes; photo by Joseph Sywenkyj for  [Image: An old Roman road in Britain; photo via

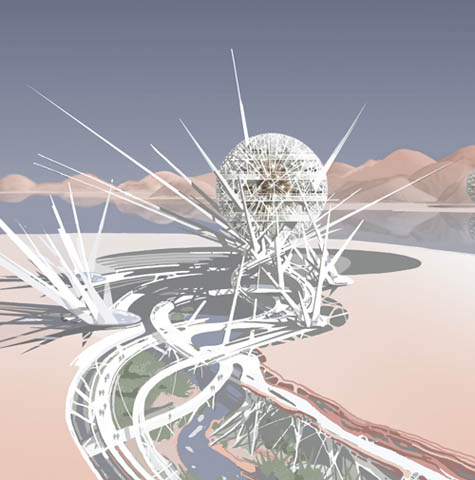

[Image: An old Roman road in Britain; photo via  [Image: Design by

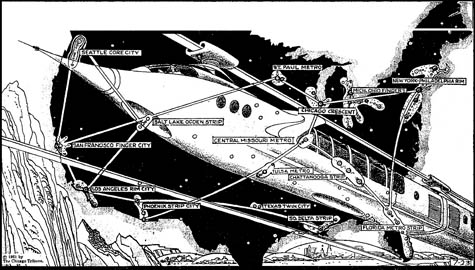

[Image: Design by  [Image: The Super-Metropolis of 1975, via

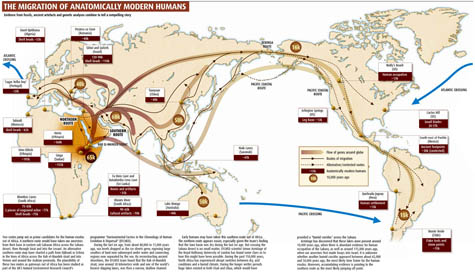

[Image: The Super-Metropolis of 1975, via  [Image: A map of possible human migration routes out of Africa and the Middle East; via

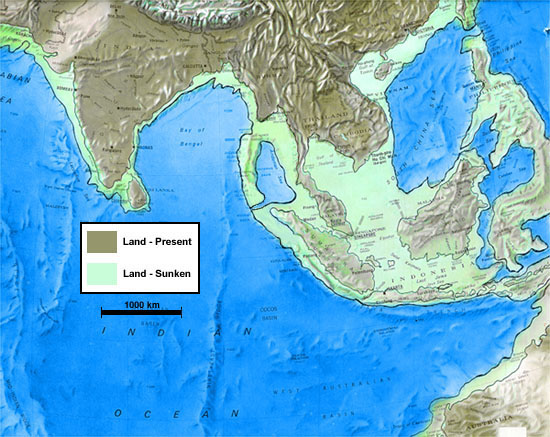

[Image: A map of possible human migration routes out of Africa and the Middle East; via  [Image: A map of southeast Asia during the Ice Age; note how much dry land there could have been. This certainly isn’t the greatest map in the world; it’s just all I could find – and it comes from a site claiming that this somehow proves Atlantis was real…].

[Image: A map of southeast Asia during the Ice Age; note how much dry land there could have been. This certainly isn’t the greatest map in the world; it’s just all I could find – and it comes from a site claiming that this somehow proves Atlantis was real…]. [Image: The Resort from the Ocean by

[Image: The Resort from the Ocean by  [Image: Photo by David Monniaux, via

[Image: Photo by David Monniaux, via  [Image: Architecture in the Costa del Sol as photographed by

[Image: Architecture in the Costa del Sol as photographed by  We’ve got

We’ve got  Also, this will only be the first of many such events: Dwell Conversations should be a really fun new series of talks, taking place in three cities over the next several months.

Also, this will only be the first of many such events: Dwell Conversations should be a really fun new series of talks, taking place in three cities over the next several months.