“Who would want to be an architect?” the Times asks. In answering that question, the article focuses more or less entirely on London’s Bartlett School of Architecture—whose students have been producing some amazing work lately, work that I have often posted about here on BLDGBLOG. Here, here, here, and here, for instance.

But, the article claims, “Leave the future to Bartlett students and we’ll all be living in car-crash spaces that occasionally come into focus as giant mechanised spindly crustacea.”

[Image: “Oops” by C. Loopus].

[Image: “Oops” by C. Loopus].

Reading such things easily prompts the familiar zing of schadenfreude—but it also seems totally inaccurate. If only it were as cut-and-dried as mistaking student work for what someone will produce professionally later; if only it were as easy as extrapolating from someone’s earliest university sketchbooks to see how they’ll someday end up.

I’m reminded here of Lebbeus Woods’s recent short essay on the work of Rem Koolhaas: there was “another Rem,” Lebbeus writes. Looking back at one of Rem’s early projects—an unsuccessful bid for the Parc de la Villette in Paris—Lebbeus suggests:

This project reminds us that there was once a Rem Koolhaas quite different from the corporate starchitect we see today. His work in the 70s and early 80s was radical and innovative, but did not get built. Often he didn’t seem to care—it was the ideas that mattered.

Over on his own blog, Quang Truong puts it more simply: “Young Koolhaas was just so punk.”

(Of course, parenthetically, Truong’s formulation opens up a whole series of possible readings through which we could interpret Rem’s ongoing career moves; we could say, for instance, that Rem is still “punk,” to use that term deliberately, but his decisions to work for clients like the Chinese government are just him giving the finger to you. That is, if punk is a universal form of energetic rebellion, then don’t assume that every punk will remain forever on your side).

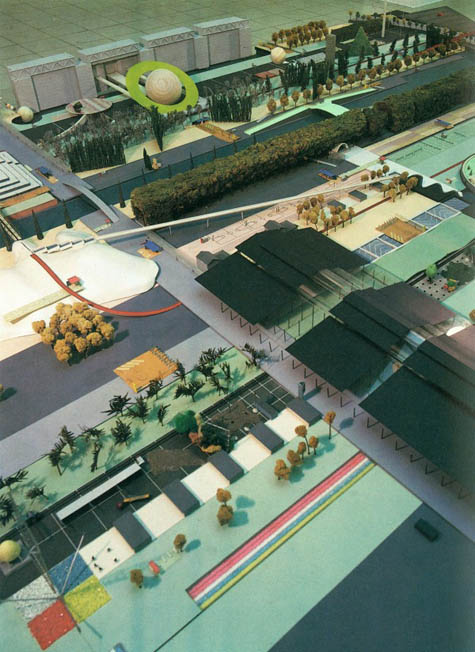

[Image: From Rem Koolhaas’s unbuilt proposal for the Parc de la Villette in Paris, via Lebbeus Woods].

[Image: From Rem Koolhaas’s unbuilt proposal for the Parc de la Villette in Paris, via Lebbeus Woods].

In any case, my point in citing Lebbeus’s essay in this context is to agree with the Times that student work can often stand on the absolute fringes of incomprehensibility, charged with the energy of poetry, myth, or confrontational politics, even verging on functional uselessness—but it’s also an ongoing joke at nearly every architecture crit I’ve been to over the past few years that, upon surviving their final day of project criticism, those students “can now get back to designing minimalist boxes.” In other words, there simply is not the assumption in these studios that now you are prepared only for the construction of rhizomes and biomorphopedic multi-agent typology swarms. There is obviously a problem if that is all you have been taught to do; but it’s not one or the other. Being taught how to make short films about architecture—more on this, below—doesn’t mean you can’t simultaneously be taught how to renovate a kitchen or how to market yourself to new clients.

The fact of the matter, anyway, is that very few clients today will actually pay to construct “car-crash spaces that occasionally come into focus as giant mechanised spindly crustacea.” If architecture school is the only time and place in which you can have the freedom to explore that sort of thing, then I don’t see any reason why you should be told not to do so. Again, if that’s all your architecture school offers you, leaving you alone to sort out the business of client management as you go, then of course your educational track needs reconsidering.

However, much of the Times‘s criticism seems predicated on the assumption that, if architecture is a vocational trade, similar to plumbing, then it cannot simultaneously be an expressive art, akin to film, painting, or literature. But, of course, it is both. In fact, the controversy more or less instantly disappears: architecture is the imaginative production of future worlds even as it is the act of building houses for the urban poor or the obtaining of technical skills necessary for rationally subdividing office floorplates.

[Image: From a project by Margaret Bursa for the Bartlett’s Unit 11, taught by Smout Allen].

[Image: From a project by Margaret Bursa for the Bartlett’s Unit 11, taught by Smout Allen].

Having said all this, the Times article ends up being a formulaic list of reasons why such-and-such an industry is doomed to fail—too many people want to pursue it, we read, not enough people want to fund it, and hardly anyone understands anymore what made it so popular in the first place. But replace the word “architecture” with “writing,” and “Bartlett School of Architecture” with “Iowa Writers Workshop”—or use “music” and “Mills College”—and you’d get a nearly identical article.

There are some very real questions to ask about the nature of architectural education today—and, when it comes to things like how architects write, I am probably in agreement with the author of the Times article (and with many of the students quoted in the piece)—but holding up the overall profitability of the industry, and the likely financial success of its individual practitioners, as the only criteria by which we should judge an architecture school seems absurd to me.

I’ll end this simply by citing some provocative statements made in the article’s comments thread—provocative not because I agree with them but because they’re well-positioned to spark debate. I’ll quote these here, unedited, and let people discuss this for themselves.

—The Bartlett “seem to want to be an architecture school and a school of alternate visual media culture at the same time. More often than not these agendas work against each other… They should make a choice and be clear about it. Are you training students to be architects or something else that has to do with architecture? What should a student expect to learn when they finish school? What are you being prepared for. If bartlett graduates go on to become film-makers, and video game designers, and such, maybe its a good idea to say it is not an architecture school and say it is a school of visual media. Then you will attract students with that goal in mind.”

—From the same commenter: “Consider, if a school opens up and starts teaching alternative medicine (acupuncture, aromatherapy, Atkins diet, chiropractic medicine, herbalism, breathing meditation, yoga,etc), gives its graduates medical degrees and sent them off to hospitals and emergency rooms to perform surgery, a lot of people would have a problem with that. This is, in effect, what the architectural profession is doing when it allows schools like the Bartlett to give architecture degrees.”

—”architectural education is still a leftover of that idea of the businessman/artiste producing unusual shapes for art critics”

—”The profession does not work. It’s economically non viable. Our work is pure iteration. Far too time consuming, and as a result, it’s impossible to charge anyone for the work we have actually done.”

And on we go…

(Spotted via @brandavenue and @ArchitectureMNP).

This is exactly why I love seeing what the Bartlett, or any school which isn't teaching what is basically structural engineering, produces each year. And why I'm jealous I didn't study there.

I struggled to get my qualifications, as my work had "visual media" at its heart. Sadly, too many incredibly creative students are put off architecture precisely BECAUSE they are forced to learn to fit their ideas into construction technology, and to simply 'pass exams', when what they want to learn is architecture as an art form. Teaching that you don't have to make something that is buildable tomorrow, but produce ideas that will change architecture is EXACTLY what schools should be doing. There's plenty guys out there who will tell you how to change it to make it stand up. Pretty sure it was Zaha Hadid who said something like:

"I take ideas to my structural engineer, not the other way around. As technology develops, one day, they might just say what I sketched IS possible." I have that on my drawing board. That's right, a drawing board.

They seem to be forgetting that pretty much every building ever built was designed like an architect, even if it looks as weird as the Centre Georges Pompidou or as boring as the tract homes endlessly iterated in America.

There's also the fact that almost no one has a single life-long profession anymore. Maybe you trained in architecture school, but go on to be a world-famous blogger and writer about architecture – or a wildly successful web comics writer, so successful it allows you to quit your architecture job.

We do crazy stuff when we're young because we know we're going to do boring stuff when we're old.

Also, you can even make the case that, until recently in human history, there never was architecture school but crazy, wonderous structures were built anyway, so maybe we don't need a school at all!

Of course, you can also take that recent article where they listed the top billionaire-producing higher education institutions in our country. #1 was Harvard, #2 was drop-out. In other words, no education is second only to THE BEST education if you want to become a billionaire.

Personally? I believe the NYT is failing journalism and going the route of sensationalism that most other American media outlets are reaching for, because controversy creates pageviews creates revenue, especially if you have a hot argument going in the comment section that keeps people coming back.

Geoff … this is a pretty important post, and I appreciate your insight here. I think it's also important to keep in mind differences between architecture education in the U.K. and the U.S., as well as difference between schools in the East and West Coast. Having been affiliated with architecture schools for the past 6 years as a critic, teacher, juror, and student in the U.S., I can only say that much of the tension you point out stems from two domains: first, the fact that architecture schools are first and foremost entrusted with preparing students for a professional career; and second, there is the studio system itself, which is aimed towards giving students the ability to defend their project in adverse situations. In short, it is a system that encourages you to be both for and against your client. And though this makes for a very productive and interesting pedagogical model, it can create some heart-wrenching friction, especially in a profession as capital-intensive as architecture.

Geoff: You touch on many important points about architectural education, some of which I've tried to address on my blog in the ARCHITECTURE SCHOOL 101-401 posts. Today, however, I'll address a less important point, concerning Rem Koolhaas.

I don't buy the 'punk' argumant as an explanation for his cooperation with authoritarian or crassly corporate clients in China, Dubai, or Europe. Rem is a master rationalizer. He has turned people's expectations upside down very effectively (he's gotten away with it) for a long time. As I say in my post DELIRIOUS DUBAI:

"One thing for sure, Rem Koolhaas doesn’t hedge his bets. He also knows how to stick his neck out and not lose his head. He has perfected the old debating trick of disarming his critics in advance. Philip Johnson was also a master at this. Before anyone could criticize the pandering commercialism of his office tower designs, he would say, “I’m a whore.” Rem Koolhaas gives this tactic a European sophistication, a rhetorically polished upgrade. He says that he is trying to “find optimism in the inevitable.” The “inevitable” sounds like fate, something beyond human control, and has an ominous ring to it. Death, of course, is the ultimate inevitable, and who could criticize someone who is defiantly optimistic in the face of that? It’s a heroic position, no doubt, if, that is, the inevitable is as certain as it is made to seem. The inevitable in Koolhaas’ discourse is the ultimate world domination by ‘liberal democracy’ and unfettered, free-market, capitalist economics at the expense of other modes of human exchange. He has set out to put an optimistic face on this inexorable process.

Koolhaas has been plying this idea for quite a few years now. In the 80s and 90s, it took the form of “in early Modernism, the heroic thing for architects to do was fight the mainstream; today it is to go along with it.”

And so on.

Rem is a gifted man, but his influence in the realm of ethics has been to show that anything can be rationalized. His brilliance and charisma make ethical compromise glamorous.

Somehow, I can't let this pass without notice.

anyone can dream…it's what normal people do while they make a living or sleep.

there is absolutly nothing to applaude about a school the pushes the envelope to an industry that doesn't exist – academic architecture.

if you want to get crazy do it in post professional grad school.

there are so many pathetic licensed architects out there already…and even if they were "creative" as Rem was in his early days it wouldn't make a difference.

if you can't build it or detail it to be built or figure out what your engineer needs to figure out – you are not an architect, at best a draftsmen with crazy ideas, crazy ideas becasause the guy who knows how to build it had that idea for about 2 seconds and then moved.

imagination and creativity in the sense of academic architecture is a joke…no wonder this profession is damn near useless.

"The profession does not work. It’s economically non viable. Our work is pure iteration. Far too time consuming, and as a result, it’s impossible to charge anyone for the work we have actually done."

I feel very sympathetic to this, although I don't know what they mean by "iteration" here. I'm a dressmaker, and if I were to bill anyone for all the time I spend researching, working out dress patterns in my sketchbook before drafting them, hunting through fabric stores, etc., the cost would be ridiculous. It's hard enough to get people to pay for the actual cutting and sewing.

In some ways though I feel like what I should be charging for is the hustling and salesmanshipping, convincing people that it is worth it to buy custom-made, because that feels like work, instead of the designing, cutting, sewing, fititng, which feels like fun. I'm sure there are plenty of architects out there who feel the same way.

A very interesting post.

Just a brief comment on Koolhaas and the Parc de la Villette. Seeing his model pictured here, it hardly looks unbuildable to me. In fact, it looks very much like Tschumi's winning bid and the park that exists today!

The Delirious track assimilates and invokes strangeness, it seems the nature of operating has been based on the intentional exploration of natural systems and their organic patterns mixed with mediated space, tech and pop materialism. Yet today we have to believe in cheap n chic and innovate in order to create from basic materials, as resources are dwindling and the age of waste and excess is over and its the age of connecting with a new system with which we can bring reflection and a timelessness…into space and its formulation is on its way.

A tutor at the Bartlett once told me: "leave the world, it will sink anyway."

The teaching at the Bartlett is of unique value and the great ideas circulating form interesting and innovative designers, but retreating into the rhetorical exercise of drawing is a risk, especially in a moment like this. Architecture students should be trying to keep the world from sinking, rather than cautiously closing themselves in small submarines, leaving punks like Koolhaas and his corporate contractors to shape our world. Being punk is stupid: get angry, design buildings, even to make just 40 square meters of our reality better.

Some of the reaction reminds me of the passage from Leon van Schaik's Spatial Intelligence which Dan Hill quoted in his commentary on the Sentient City exhibition:

“To complete with this practical glamour our forebears went to the heart of making in architecture – its technologies of carving, moulding, draping or assembling – when they staked their claim to be caretakers of a body of knowledge for society. The architectural capacity to think and design in three and four dimensions, our highly developed spatial intelligence, was overlooked, and for the profession space became, by default, something that resulted from what was construction … What if our forebears had professionalised architecture around spatial intelligence rather than the technologies of shelter? Might society find it easier to recognise what is unique about what our kind of thinking can offer?”

Interesting that the work at Bartlett is described, essentially, as an assault on the status of the profession as a body of technical knowledge (particularly here, which was linked in the comments at the Times) — that if you have time to do these things in school and yet still go by the same title 'architect', then that implies that the technical knowledge is not essential to being an architect — while, from another perspective, the strict delineation of architecture as that body of technical knowledge can be seen as the root of the marginalization of architecture. The trick, though (as Anon 12:34 says), is that it is relatively easy to convince a client that technical knowledge is worth paying for, and relatively difficult to convince a client that the deployment of other kinds of architectural knowledge — whether 'the imaginative production of future worlds' or 'spatial intelligence' — is worth funding.

Lebbeus, I'm a reader and a fan of your Architecture School series, which I'll link to here for ease of reference:

Architecture School 101

Architecture School 102

Architecture School 201

Architecture School 202

Architecture School 301

Architecture School 302

Architecture School 401

AS401 Buffalo Analog

The series is worth reading.

But I want to point out that I tried quite carefully to frame and qualify my comment about Koolhaas and "punk." My point was not to say that I do, indeed, think Koolhaas's early work was "punk," and that Rem has, in fact, kept this strain of rebellion alive in his work by accepting commissions from politically suspicious clients—i.e. working for the Chinese government is Rem's way of spray-painting the walls of Western morality, like wearing a swastika t-shirt or getting drunk on national television.

What I was trying to say is that, if we accept Quang Truong's formulation, that Koolhaas was just so punk, then this opens up the interpretive possibility that Rem is still punk, only he is no longer on Truong's side; that is, when a person you once admired for his or her rebellious inclinations begins to rebel against you, it's easy to feel like they've gone over to the dark side.

But all of that first requires that we accept the formulation that Rem was punk—and I didn't mean for my citation of the statement to come across as blanket endorsement.

Who knows if that makes any more sense! But that was the original impulse behind my parenthetical comment about Rem and punk.

Having said that, though, it's a legitimate question: When your own preferred figures of rebellion begin to mock you, how are you supposed to understand that switch in positions? Have you changed, or have they?

Re: Geoff "Have you changed, or have they?"

Yes.

What bunk? Most intelligent students get exactly what typical architectural schools are pushing. It's a farce. They tell you to design some unbuildable gee-whiz piece of crap, and they go home to they're lovely traditional homes in the historic part of town. They tell students who question that they are simplistic morons, but when they're non-architect mate says "I like gothic, or potery barn" they say ok.

If architectural school where engineering school, we'd all be living in caves. If architectural school where art school… it already is.

i didnt know there were any architecture schools that taught architecture.

What a cynical bunch we are! As someone who enjoyed the esoteric frivolity of architecture school whilst working in the brutal economic reality of practice (the latter as part of my degree no less), I'm sure I'm not the only one who experienced and thoroughly enjoyed the best of both worlds.

If I’d merely wanted technical knowledge, I would have gone to a college program in architectural technology, or more likely, into engineering school. I didn’t want that. This article implies that university should be about teaching skills, not necessarily getting an education; that age-old argument. I will always be grateful for the emphasis my architecture school placed on multi-disciplinary, theoretically-demanding, and craft-based endeavors. That such projects resulted in time-space impossibilities, scaled impracticalities, and a lack of building code analysis was not the point. The point was we all emerged as citizens with highly refined spatial sensibilities, a tendency to look beyond the obvious, and a comfort level in activities as diverse as literary analysis and welding. (and yes, even the latter two have come in handy over the years) Some of us went on to be filmmakers, artists, etc., but everyone who wanted to become an architect did so, and as we are now partners and associates in our chosen firms, our so-called crazy architectural education is a continuous source of inspiration and formation in our daily work.

Architecture school is like law school in that one spends years there studying the field and learning principles and approaches, then one has to take a whole new course on how the law actually works in order to practice. Of course, not everyone who goes to law school practices law, nor does every architecture student practice architecture.

I think the whole process of design school, or at least the ones like Bartlett, is to teach you to think for yourself, and to hon that skill.

Not everyone can think like this, but basically people pay architects to think of things that they couldn't, and that is exactly what is being taught at Bartlett it seems to me.

Yes, there is a rigor to being a professional that must be learned too, but that is best honed in a professional setting. Architects must be creative and practical at the same time. A difficult feat.

Perhapes the designs at bartlett are underconstrained, but I don't get that impression. I think the constrants are probably a little more off the wall that in the real world, but as long as you are learning to be creative whil keeping mind the constraints of the context in which yo uare designing, you are learning a valuable skill.

I say Bravo to Bartlett's approach.

Saint – Just curious as to who you're referring to when you wrote "or a wildly successful web comics writer, so successful it allows you to quit your architecture job."

I think Saint might have been referring to me except I am neither wildly successful, neither have I quit my architecture job. 🙂

Anyway, here is my response to some of the questions raised here:

My Response