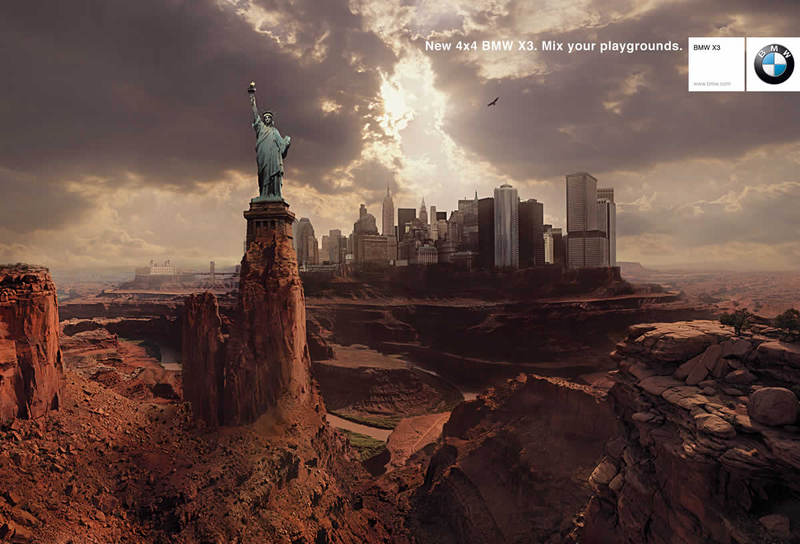

[Image: Another ad for BMW – see the one featuring London – this time transforming New York City into a desert city on the Arizona-Utah border, perched on geological outcrops and overlooking slot canyons. Rumor has it, Lebbeus Woods has an image much like this…? Ad discovered via Design Bivouac, thanks to a tip from Kosmograd. View a slightly larger version].

[Image: Another ad for BMW – see the one featuring London – this time transforming New York City into a desert city on the Arizona-Utah border, perched on geological outcrops and overlooking slot canyons. Rumor has it, Lebbeus Woods has an image much like this…? Ad discovered via Design Bivouac, thanks to a tip from Kosmograd. View a slightly larger version].

Year: 2007

New York City in Sound

[Image: Manhattan, as photographed by Dan Hill].

[Image: Manhattan, as photographed by Dan Hill].

Back in April, BLDGBLOG interviewed Walter Murch. Murch has been a film editor and sound designer for nearly four decades; he has won three Oscars and two BAFTA Awards in the process (among many other accolades); and he is the subject of an excellent, often riveting, book-length collection of interviews, called The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film, conducted and assembled by novelist Michael Ondaatje.

You can read the BLDGBLOG interview with Murch here – where you’ll notice that I ask Walter, toward the end of our discussion, about sounds and the city: what makes cities sound the way they do?

Can these acoustic properties be artistically re-shaped, or somehow musically used?

In response, Murch cites a short essay written by filmmaker Michelangelo Antonioni in which Antonioni describes what it feels like to listen to Manhattan – as one would listen to a distant symphony, or to the sounds of a unfamiliar instrument.

That essay, with a new introduction by Walter Murch, is now reprinted here, in full, on BLDGBLOG.

by Walter Murch

Manhattan: remorseless grid of right-angle streets rescued by a jumble-sale of architectural styles thrown together by history and human will-power. Paris (or Prague, or perhaps any other European city): ancient broken crockery of random-angled streets repaired by architecture of great stylistic and cultural coherence.

Confronted with the classically American paradox of Manhattan’s simultaneous rigidity and exuberance, the refined European sensibility discovers that…

…beauty in the European sense has a premeditated quality. There was always an aesthetic intention and a long-range plan. That’s what enabled Western man to spend decades building a Gothic cathedral or a Renaissance piazza. The beauty of New York rests on a completely different base. It’s unintentional. It arose independent of human design, like a stalagmitic cavern. Forms which are in themselves quite ugly turn up fortuitously, without design, in such incredible surroundings that they sparkle with a sudden wondrous poetry.

—Franz, from The Unbearable Lightness of Being by Milan Kundera

Growing up on Riverside Drive in Manhattan, I never questioned the stalagmites in which we lived: our gang would roam across the rooftops, scrambling up and down the two or three stories difference in height between adjacent apartment buildings, all erected in the 1890s in different vernaculars of the Italianate Palazzo style. The cornices that capped taller buildings would jut perplexedly into thin air, and the cornices of shorter ones would nuzzle up awkwardly against the window of someone’s bathroom.

It was only years later when I was living in the Prati district – Rome’s version of Manhattan’s Upper West Side – that I saw cornices as they were intended: a continuous horizontal line atop several buildings, gathering them together in a single conceptual frame. When I returned to my old neighborhood in Manhattan, it now looked wondrously stalagmitic.

Sometime after the success of his film Blow-Up (1966), the Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni visited Manhattan, thinking of setting his next project in New York. Confused and overwhelmed by the city’s visual foreignness, he decided to listen rather than to look: to eavesdrop on the city’s mutterings as it emerged into consciousness from the previous night’s sleep. Sitting in his room on the 34th floor of the Sherry-Netherland Hotel, Antonioni kept a journal of everything he heard from six to nine in the morning… Perhaps some inadvertent sound might provide the key to unlock the mysteries of this foreign world.

[Image: Looking down at the roof of Manhattan’s Sherry-Netherland Hotel, via New York Architecture Images].

[Image: Looking down at the roof of Manhattan’s Sherry-Netherland Hotel, via New York Architecture Images].

His New York film was never made, but the pages of Antonioni’s bedside vigil survive, and were published at a conference on film sound that I attended in Copenhagen in 1980. The organizers of that conference – composer Hans-Erik Philip and filmmaker Vibeke Gad – have generously allowed BLDGBLOG to reprint Antonioni’s poetic soundscape of a long-vanished Manhattan, filtered through the Italian sensibility of his acutely sensitive cinematic ear.

The soundtrack for a film set in New York – circa 1970

by Michelangelo Antonioni

There is a constant murmur, hollow and deep: the traffic. And another sound, intermittent: the wind. It comes in gusts, and in the pauses I can hear it sighing, far away, against other skyscrapers. Here, on the thirty-fourth floor, I can feel the vibration of every gust. It gives me a strange feeling as if, for a few moments, my brain freezes. A faint, short-lived siren comes and goes. The noise of two car-horns. A rumble that approaches but is impatiently eclipsed by a sudden buffet of the wind. A tram car.

It is six o’clock in the morning. Another rumble blends with the first, then drowns it. A faint explosion, far, far away. The wind returns, rising from nothing, spreading, it seems to stretch in the still air, then dies. The hint of a tram, faint, remote. It is not a tram, after all, but another kind of sound I cannot recognize. A truck. A second one, accelerating. Two or three passing cars. The roads in Central Park twist and turn. A line of cars. Their exhausts a kind of organ playing a masterpiece. A moment of absolute silence, eerie. A huge truck passes. It seems so close that I feel I am on the second floor. But that sound, too, quickly fades. A squeal. A ship’s siren, prolonged and melancholy. The wind has dropped. The siren again. The murmur of traffic beneath it. A bell, off key. From a country church. But perhaps it is the clang of iron and not a bell. It comes again. And still once more. A car engine races, furiously, with a sudden spurt of the accelerator. In a momentary hush, the siren again, far away. The metallic echo rises. A terribly noisy truck seems just outside the window. But it is an aircraft. All the sounds increase: car-horns, the siren, trucks; and then they recede, gradually. But no, another rumble, another siren. Irritating, persistent, right across the horizon.

Quarter past six: the same series of sound in waves, each in turn, clearly defined. Brief intervals. A murmur continues. And, always, the siren. An abrupt car-horn, very far away. Another muffled beneath it. Somewhere on a distant street, a car, very fast, perhaps European. The wind swirls against the wall outside. A single gust., immediately swallowed by a raucous truck and then a newer vehicle, steadier. The throb of the two different motors driving off, merging into one. But it is not a truck, it’s an aircraft. No. Not an aircraft. A noise that rises and becomes deafening, only to fade unidentified. All that remains, obsessive, is the siren. And someone whistling (how can that be possible?) instantly drowned by an angry car-horn. Sounds of metal sheets thrown together. Clear and sharp, a winch. The sound of cogs. But it cannot be a winch, and this constant whine is not the siren. More sheets, more metallic. Then a hollow boom, barely audible, but lingering in the air. A faint hum suddenly stops. A car passes, another, then a third, fading, fading, fading. They mingle with other cars, other sounds. An aircraft seems to take off from right beside the building. And as suddenly as it appeared, it is gone. The very beautiful roar of a car, completely appropriate for this moment. It speeds past and dies, distinct, satisfying. Two tones shimmer. A gust of wind.

[Image: A view of Central Park, via Wikipedia].

[Image: A view of Central Park, via Wikipedia].

Half past six: more gusts. A furious flurry of wind between the skyscrapers slides away and buffets across the park. Only a car-horn interrupts, like a slap in the face. The wind drops. A peal of bells in the stillness. And always, the siren. A tone higher now. It wasn’t bells. It is my Italian ear that hears it that way. The sheets of metal. A short clatter, like gunfire. A train passes, perhaps the elevated. A peal, prolonged, and then the siren, abrupt. Gone. The sounds change in a moment, they arise and die again immediately. The hum reasserts itself, advancing like a camouflaged army, approaches, closes in, on the alert, ready to take over completely. It is very close. One can distinguish the wind, the cars, the aircraft, a clash of iron, and the siren. They advance, determined, against this skyscraper hotel. In the forefront, the sound of iron, but the aircraft closes in and takes over alone. And now – nothing. The struggle is over. A small revolution quelled by the authority of a car-horn. The banging of wood. A pause. More banging. They must be moving tables. It sounds like a machine gun that is falling apart. The cars are under fire. They have to pull up and stop. Another siren, more real. The rumble of wheels, but it is not a car. It is the wind, which has risen again. Strong, but not strong enough to cover the aircraft.

Cars. A roar, as if from a cannon, echoless. Here and there, metallic sounds of various intensities. A roar of wind. The roar of a truck. The roar of the elevated railway. Two thuds in different tones. The noise grows and then stops suddenly, as if cut off by the thuds as they start again. Other sounds are born, clear yet unrecognizable. A long, startling car-horn. A sound that does not die, that will never die. I cannot hear it any longer, but it has left me with this certainty. But the sound of the siren is dying. A gust of wind pushes it away, but a truck rises. Then diminishes in turn and mingles with the wind. Some kind of bell.

A voice is heard. The first voice.

Seven o’clock: A blast from the siren, as if to remind me of its existence. Now imperceptible, yet insistent. The squeal of tires. A thundering, a rumble, somewhere underground.

Half-past eight: And now the sun has risen, but the sounds are still the same. With one exception. Drills. Nasty. Destroying a building. They are far away but occasionally, because of the wind, they are perfectly distinct. The other sounds remain. A whistle, shrill, anxious. It repeats – urgently. A noisy engine, I don’t know what kind. And loud, yet distant, the drills. The only change is that it has all become stronger with the daylight. The wind, the cars, the siren. Only the car-horns are less strident, more discrete, a reflection on the drivers who obey New York’s traffic laws: they must use their horns only when absolutely necessary. They cannot afford the fines, and so they obey the law, which seems a little Teutonic. I imagine the drivers in this bewildering noise, melted together, inside their creeping cars: noise that hasn’t the courage to explode, but hovers in the air, in the spring-like, clear, clean winter air.

(BLDGBLOG owes a huge and genuine thank you to Walter Murch, Hans-Erik Philip, Vibeke Gad, and, of course, Michelangelo Antonioni for the permission to reprint this essay. Meanwhile, if this post appealed to you, I’d urge you to take a look at BLDGBLOG’s interview with Walter Murch, where some of these points are developed further – or simply to pick up a copy of The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film, edited by Michael Ondaatje. Of course, Murch is both the subject and author of many other books and articles – links to which can be found embedded in the BLDGBLOG interview. Finally, keep an eye out for Antonioni’s own The Architecture of Vision: Writings and Interviews on Cinema, due out in November 2007).

The Sun, the Grid, and the City

Whilst doing research for an article I’m writing, I found myself browsing through some articles by Sam Roberts of The New York Times. I bookmarked one of them for future reference – only to realize, about half an hour ago, that it was published exactly one year ago today.

So I decided to put it up on BLDGBLOG.

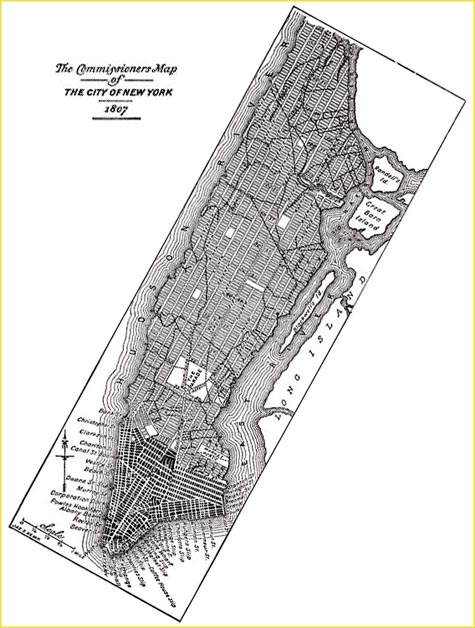

As it happens, then, Manhattan’s mathematically rational street grid is actually rotated 29º off the north-south axis – and this angle has interesting astronomical side-effects.

As it happens, then, Manhattan’s mathematically rational street grid is actually rotated 29º off the north-south axis – and this angle has interesting astronomical side-effects.

In other words, because of the off-center orientation of Manhattan’s street grid, you can only see the setting sun “down the middle of any crosstown street” on two specific days of the year: May 28 and July 13.

July 13 is, of course, next week – so watch out for it.

Manhattan is a solar instrument that only works twice.

So, because of historical decisions made about the logic and purpose of urban planning – and because of the declination of the Earth’s poles – the streets of Manhattan are aligned with the setting sun only two times a year.

Which means that New York is a kind of Hugh Ferrisian Stonehenge: casting shadows on itself till the days when it can truly begin to shine.

In any case, Roberts points out, interestingly, that a rectilinear street grid was not the only arrangement of space considered viable for Manhattan during its earliest days of European settlement:

William Bridges, the city surveyor, explained that one of the commissioners’ chief concerns was ”whether they should confine themselves to rectilinear and rectangular streets, or whether they should adopt some of those supposed improvements, by circles, ovals and stars, which certainly embellish a plan, whatever may be their effects as to convenience and utility.”

Needless to say, the “circles, ovals and stars” lost out to squares and rectangles.

Manhattan is thus now “a nearly perfect place to practice taxicab geometry,” Roberts continues: it is an island “in which the shortest distance between two points is rarely a straight line.”

And yet Manhattan is also an island of astronomical coincidence that, like any structure standing on the surface of the Earth, lines up with the heavens in its own peculiar way.

(Earlier on BLDGBLOG: The architecture of solar alignments).

Movement

The last twelve months have seen all kinds of hellzapoppin’ for BLDGBLOG, from the move out to Los Angeles to the BLDGBLOG book, to a wide variety of other things, including Postopolis!; but the movement isn’t over…

In just two months’ time I’ll be moving up to San Francisco to become a Senior Editor at Dwell magazine.

[Images: The most recent five covers from Dwell magazine].

[Images: The most recent five covers from Dwell magazine].

The job itself looks awesome – and a lot of fun – and it’s in a great office, near the Transamerica Pyramid, only one block away from an architecture bookstore, and I’ll have some really cool co-workers, and a great boss with good taste in German beer, and I’ll even be near my publisher during the book design process, so I’m excited. I can go for walks in the Muir Woods! And look at the Golden Gate Bridge and walk across the hulls of abandoned 19th-century frigates.

A few quick things:

1) BLDGBLOG will continue – in fact, I’m using the entirety of this week to finish up all other freelance commitments, leaving just BLDGBLOG, the BLDGBLOG book, and Dwell. So BLDGBLOG isn’t going anywhere.

2) This doesn’t mean that Dwell will suddenly turn into BLDGBLOG, or vice versa. Dwell, as far as I’m aware, won’t be covering, say, J.G. Ballard and the apocalypse, or gold star hurricanes, or statue disease, or the novels of Rupert Thomson (although they might start covering Mars bungalows – who knows – and the speculative urban futures of global climate change…). But those stories will continue to appear here on BLDGBLOG.

3) I’m a little nervous… A new job… another new city…

4) This also doesn’t mean that Dwell endorses everything – or anything – that I have to say here on the blog; so if I get something wrong, or if I say something stupid… it’s my fault alone.

5) Nervousness aside, I’m incredibly excited about the editorial directions all of this could go in, and I can’t wait to start. I’ve already got a long list of (sometimes absurd) things that I’d like to cover at Dwell, and I really think this is going to be a good time.

[Images: Five more covers from Dwell].

[Images: Five more covers from Dwell].

Anyway, it’s strange to think that I’m leaving Los Angeles! I thought I’d be living here for at least the next 9 or 10 years, growing cancerous and leathery in the sunlight, throwing events about science fiction and the city, so there are loads – and loads – of things that I’ve been meaning to do here that I’ll now just have to squeeze into less than eight weeks.

I’ll miss everything!

The desert! Joshua Tree! Zion National Park! Arizona! The Center for Land Use Interpretation! Baja California! SCI-Arc! The Hollywood Hills! Hell, I’ll even miss the ArcLight.

And I live right across the street from Sony Studios, so nighttime walks past huge, well-lit hangars inside of which films are being produced will become a thing of my southern Californian past…

Anyway, I’ll be in San Francisco starting September 1st or thereabout. And, if you’re in the market for something to read, consider subscribing to Dwell.

Gold Star Hurricane

[Image: A stunning photograph of the Rosette Nebula, taken by Ignacio de la Cueva Torregrosa, courtesy of NASA’s Astronomy Picture of the Day archive. View larger!].

[Image: A stunning photograph of the Rosette Nebula, taken by Ignacio de la Cueva Torregrosa, courtesy of NASA’s Astronomy Picture of the Day archive. View larger!].

A few bits of astronomical news seem worth repeating here on BLDGBLOG:

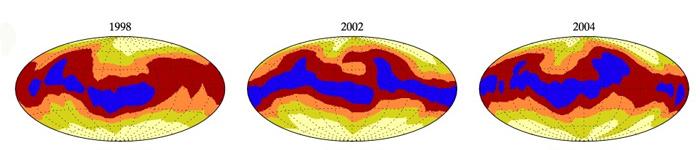

1) Weather has been observed on the surface of a star for the first time. Astronomers have now seen “mercury clouds” moving through the turbulent skies of “a star called Alpha Andromedae.”

[Image: Weather on a star; via New Scientist].

[Image: Weather on a star; via New Scientist].

Because the star does not have a magnetic field, however, scientists have been left scratching their heads over what causes the clouds to form; for the time being, then, no one really knows where these things come from.

I wonder, though, how far this “weather” metaphor really goes: are there storms, and hurricanes, and tornadoes? Is there actual convection up there, in the outer atmosphere of Alpha Andromedae, and, if so, is there ever precipitation – frozen mercury snowing down toward the star’s core on slow currents of helium gas?

While we’re on the subject, I’m also curious if there are any religious systems that use “hurricanes of mercury” as a kind of divine threat. You will be struck down by a hurricane of mercury…

After all, aren’t Mormons worried about being consumed by “hurricanes of fire”?

In which case a hurricane of, say, argon – or a tornado of germanium – isn’t all that much of a stretch.

[Image: A reflection nebula in Cepheus, beautifully photographed by Giovanni Benintende, courtesy of NASA’s Astronomy Picture of the Day].

[Image: A reflection nebula in Cepheus, beautifully photographed by Giovanni Benintende, courtesy of NASA’s Astronomy Picture of the Day].

Or perhaps a hurricane of transition metals could come blowing in over the islands of Stockholm, coating that city in a smooth new shell of mineralogical forms…

2) Meanwhile, some stars are apparently plated in gold.

“Scattered through space,” we read, “are some peculiar stars that seem to contain more gold, mercury and platinum than ordinary stars such as our Sun.”

These stars are referred to as being “chemically peculiar.”

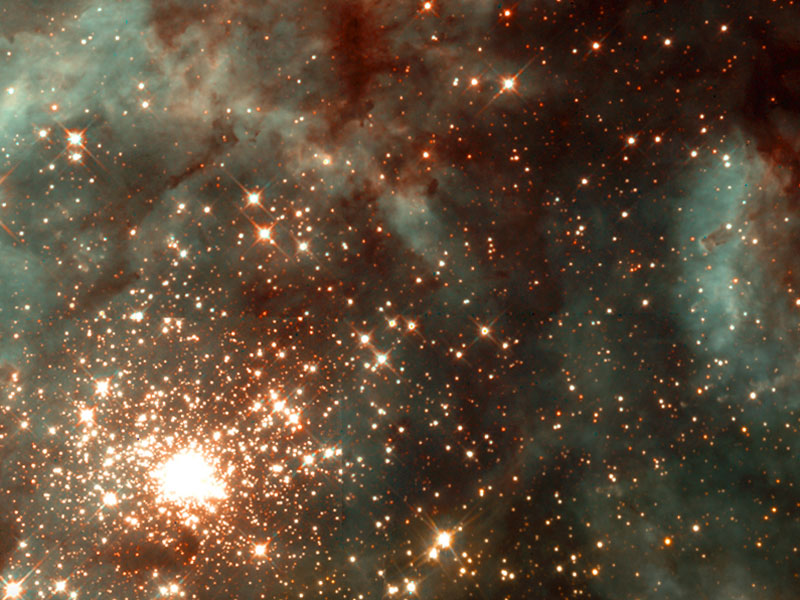

[Image: Star Cluster R136, photographed by NASA, et. al.].

[Image: Star Cluster R136, photographed by NASA, et. al.].

One star, in particular, which astronomers have named “chi Lupi,” has 100,000 times as much mercury as the Sun, and 10,000 times as much gold, platinum, and thallium.

What’s really, really cool about this, though, is that chi Lupi can apparently be thought of as a series of concentric shells, where each shell consists primarily of one element; the locations of these shells are determined by the atomic weights of the elements they contain.

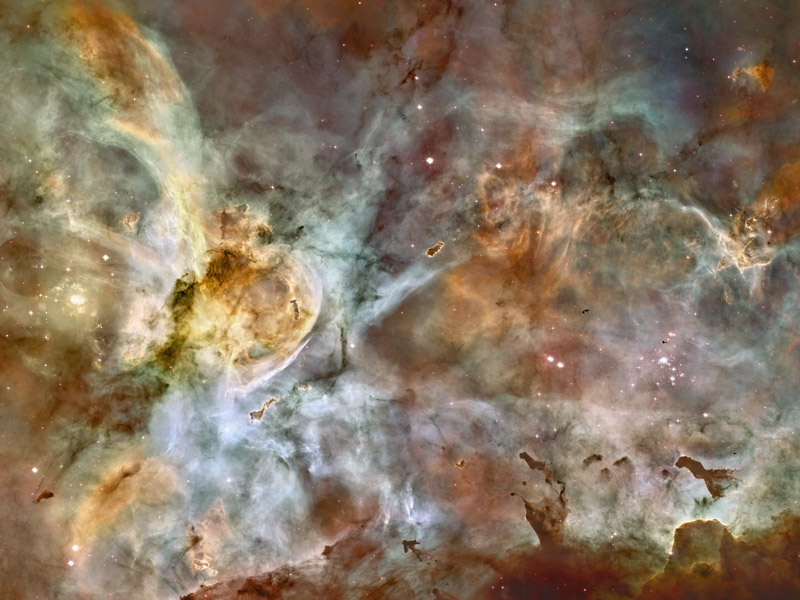

[Image: The Carina Nebula, photographed by NASA, et. al.; view bigger!].

[Image: The Carina Nebula, photographed by NASA, et. al.; view bigger!].

In other words, “the heavy metals in the star were pushed outwards by the radiation pressure of the star’s ultraviolet light, but were kept from escaping by gravity.” On chi Lupi, for instance, there is a shell of mercury in the “stellar photosphere.”

Thin outer layers of gold can thus be found on this and other “chemically peculiar” stars throughout the universe.

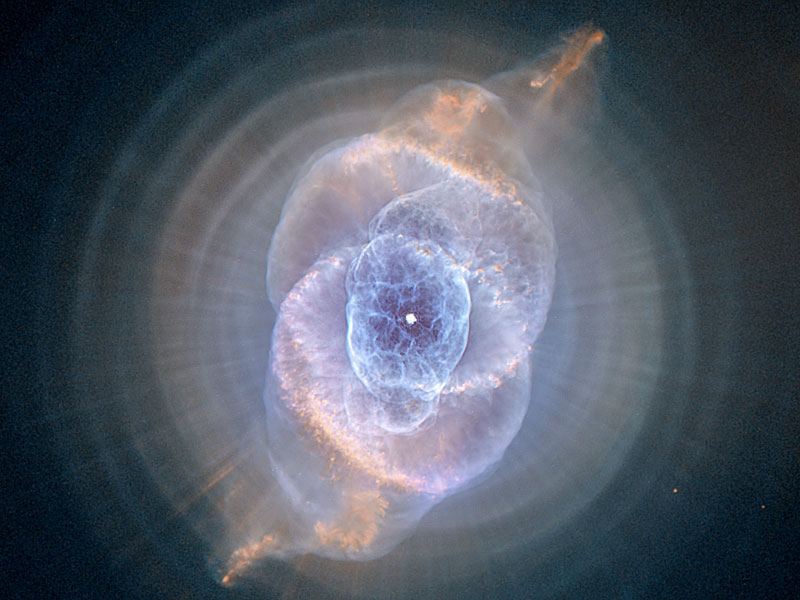

[Image: The Cat’s Eye nebula, photographed by NASA, et. al.].

[Image: The Cat’s Eye nebula, photographed by NASA, et. al.].

3) Finally, we’ve all heard about things like this before, but “one of the largest and most luminous stars in our galaxy” is also “a surprisingly prolific building site for complex molecules important to life on Earth.”

The discovery furthers an ongoing shift in astronomers’ perceptions of where such molecules can form, and where to set the starting line for the chain of events that leads from raw atoms to true biology.

That “true biology” can be tracked back to the stars is nothing new; but the fact that a star called VY Canis Majoris – “a red hypergiant star estimated to be 25 times the Sun’s mass and nearly half a million times the Sun’s brightness” – is burning with pre-biotic compounds, “including hydrogen cyanide (HCN), silicon monoxide (SiO), sodium chloride (NaCl) and a molecule, PN, in which a phosphorus atom and a nitrogen atom are bound together,” is apparently reason to get excited.

[Image: The Ophiuchius reflection nebula, photographed by Takayuki Yoshida; courtesy of NASA’s Astronomy Picture of the Day].

[Image: The Ophiuchius reflection nebula, photographed by Takayuki Yoshida; courtesy of NASA’s Astronomy Picture of the Day].

First, let me quickly say that I love – love! – the idea that biologists might someday study stars in their quest to understand the chemical origins of molecular biology; and, second, I’m curious if we could combine these three articles – asking: could storms of living matter form on the outer surface of a star, reaching hurricane strength as they blow in whorls and vortical currents across gold-plated skies?

The first astronomer to discover a living storm should win some sort of prize, I think.

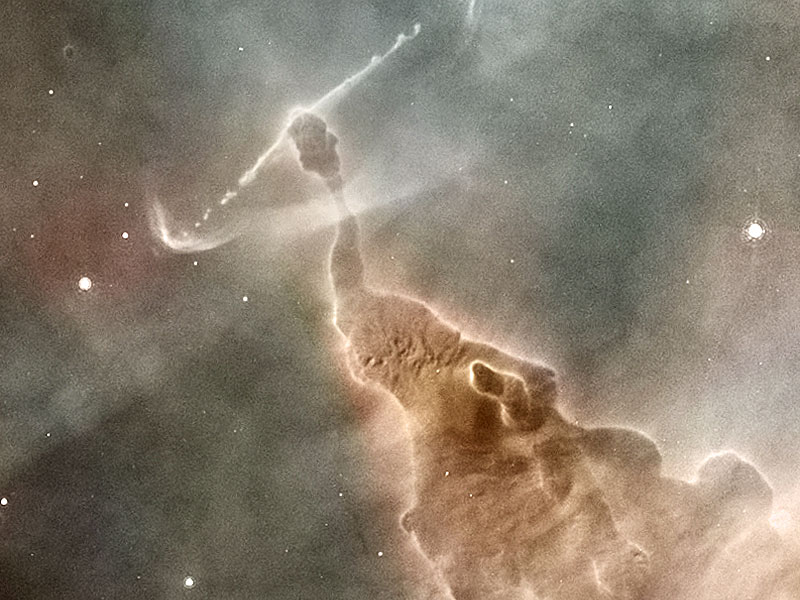

[Image: The Carina Nebula, via NASA’s awesomely fun Astronomy Picture of the Day

[Image: The Carina Nebula, via NASA’s awesomely fun Astronomy Picture of the Day

].

In any case:

Even simple phosphorus-bearing molecules such as PN are of interest to astrobiologists because phosphorus is relatively rare in the universe – yet it is necessary for constructing both DNA and RNA molecules, as well as ATP, the key molecule in cellular metabolism.

These chemicals “can later find their way into newborn solar systems” – although it had been thought that “any molecules that condensed from the cooling, expelled gas would later be destroyed by the intense ultraviolet radiation emitted by the star.”

An expanding star, it was thought, like something out of the Greek myths, thus sterilized its progeny.

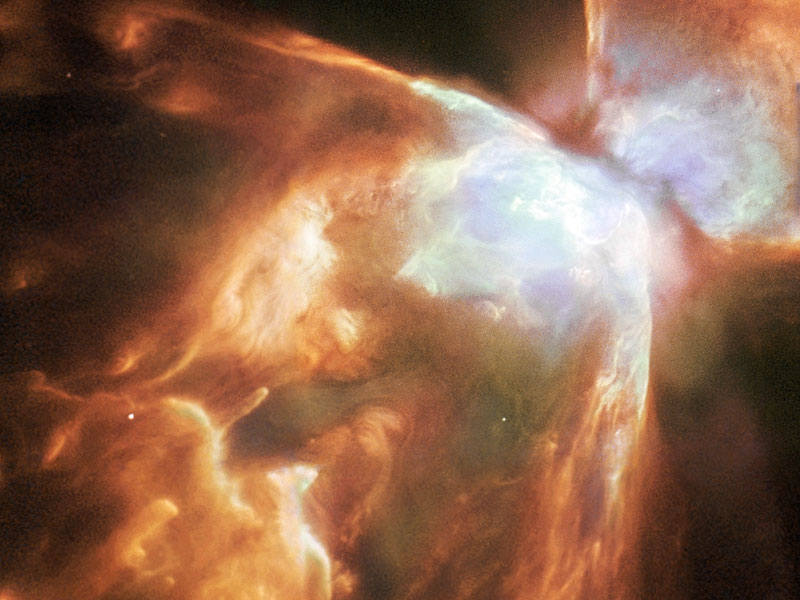

[Image: NGC 6302 – like some sort of exploding angel – photographed by A. Zijlstra and NASA].

[Image: NGC 6302 – like some sort of exploding angel – photographed by A. Zijlstra and NASA].

But there’s good news for we living creatures: the “ejected material” that later seeds fledgling solar systems with prebiotic compounds also “contains clumps of dust particles that apparently shield the molecules and can shepherd them safely into interstellar space.”

Note the “shepherd” metaphor.

Anyway, this all seems to suggest “that the chemistry that leads to life may be more widespread in the universe and more robust than previous studies have suggested.”

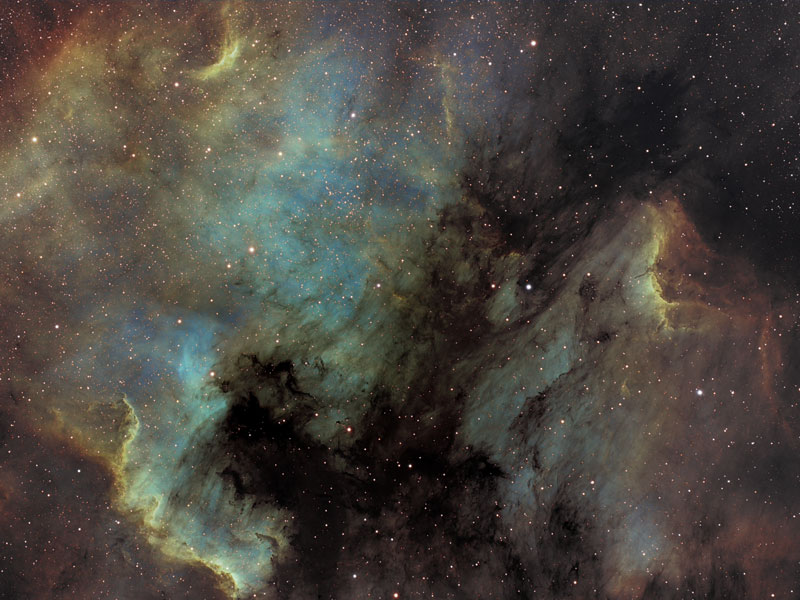

[Image: NGC 7000, the North America nebula, alongside the Pelican nebula; photographed by Nicolas Outters, courtesy of NASA’s Astronomy Picture of the Day].

[Image: NGC 7000, the North America nebula, alongside the Pelican nebula; photographed by Nicolas Outters, courtesy of NASA’s Astronomy Picture of the Day].

These astrobiological studies will soon be helped along by a “high-altitude radio interferometer, consisting of 50 dishes – each 12 metres wide – currently under construction” in Chile’s Atacama Desert.

[Image: Another view of NGC 7000; I can’t find the origin of this photograph, unfortunately – but the minute I can credit this to the appropriate photographer or institution, I will do so!].

[Image: Another view of NGC 7000; I can’t find the origin of this photograph, unfortunately – but the minute I can credit this to the appropriate photographer or institution, I will do so!].

(Earlier on BLDGBLOG: The uttermost reaches of solar influence, Struck by loops, An electromagnetic Grand Canyon, moving through space, Bulletproof, and Planetarium Among the Dunes).

London Canyonlands (pt. 2)

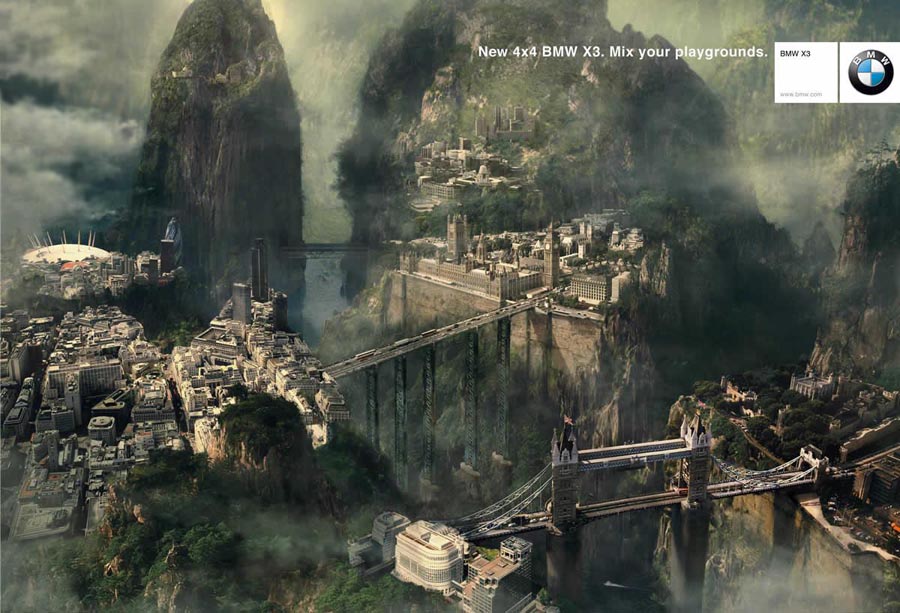

[Image: A BMW ad, showing us London geologically mixed, across a series of bridges and viaducts, with, say, Rio de Janeiro, Angkor Wat, and maybe… Macchu Picchu? View larger. Found via things magazine].

[Image: A BMW ad, showing us London geologically mixed, across a series of bridges and viaducts, with, say, Rio de Janeiro, Angkor Wat, and maybe… Macchu Picchu? View larger. Found via things magazine].

(Earlier on BLDGBLOG London Canyonlands and Offshore (again)).

More space in the space hotel

[Image: Outside the space hotel… in space. You can see the Earth’s curvature in the lower right-hand corner. Courtesy of Bigelow Aerospace].

[Image: Outside the space hotel… in space. You can see the Earth’s curvature in the lower right-hand corner. Courtesy of Bigelow Aerospace].

The space hotel is back in the news.

According to the BBC, an “experimental spacecraft designed to test the viability of a hotel in space has been successfully sent into orbit” by a private company called Bigelow Aerospace.

The “inflatable and flexible core of the spacecraft expands to form a bigger structure after launch.” Which is helpful, because Bigelow’s ultimate goal is “to build a full-scale space hotel, dubbed Nautilus, which will link a series of inflatable modules together like a string of sausages.”

However, two distracting bits of news then enter the story…

First, the BBC reports that “the company has sent a collection of pictures and other memorabilia from fee-paying customers keen to see their personal possessions photographed in space.” And, second, we learn that the company “also hopes to activate a space-based bingo game to be played by people back on Earth.”

1) Why would you want your personal possessions to be photographed in space? Here’s my desk lamp… in space. Here are my dinner plates. Here is my couch.

2a) Does “space-based bingo” somehow augment one’s experience of the game? I suppose it would. How does it work? Would there actually be an astronaut up there calling out numbers? And would you have to get up there in order to collect your prize?

2b) What about space-based Trivial Pursuit? An unnamed man, or woman, in orbit over the Earth’s surface starts asking a series of difficult questions about history, science, politics, and the arts. The start of the game is never announced; the questions are broadcast on an AM radio station; you never know if you’ve won.

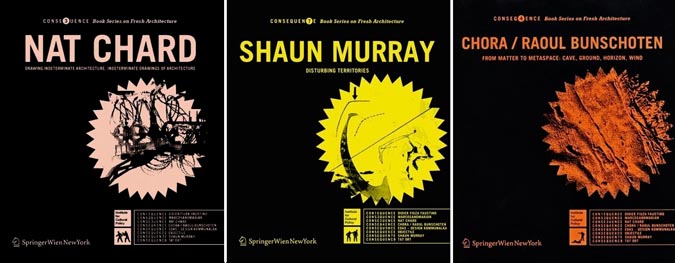

Disturbing Indeterminate Horizons of Fresh Architecture

[Images: Three covers from Springer‘s Consequence Book Series on Fresh Architecture].

[Images: Three covers from Springer‘s Consequence Book Series on Fresh Architecture].

Does anyone know anything about these books? More specifically, have you read them – and, if so, how are they? Well-produced? Interesting? Over-academic? Boring? Life-changing and amazing?

I can only find the most basic book descriptions online – and most of those are in German – and I would simply order one of these to see what they’re actually like (I don’t have access to an architecture library) but they seem a little bit over-priced. A 100-page pamphlet for $25.95…?

Anyway, if anyone’s ever run across one of these, let me know. The three books, above, are by Nat Chard, Shaun Murray, and Chora/Raoul Bunshoten, respectively.

Thanks!

The Deck

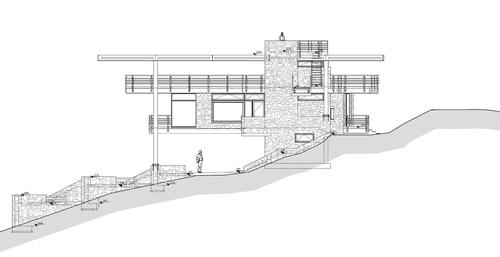

[Image: Sergio Bianchi’s Bellegra retreat, via Metropolis].

[Image: Sergio Bianchi’s Bellegra retreat, via Metropolis].

In an unfortunately subscriber-only article, Metropolis calls our attention to “an artists’ retreat in Bellegra, a small town 40 miles southeast of Rome.”

The building, we read, was designed by Sergio Bianchi, whose “idea for a Modernist villa designed according to the principles of organic architecture,” proved to be so controversial in the context of Italy’s “archaic building laws” that it took more than six years to construct.

The design itself was “inspired” by Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater. Metropolis writes that, “although the villa – which has a biological sewage system and a roof fitted for solar panels – is more visually and environmentally harmonious with the landscape than its neighbors, a group of squat clay-tile-roof stucco homes, it provoked strong resistance from local authorities.”

Those authorities said, somewhat unbelievably, that the building “was too much like science fiction.”

[Image: Sergio Bianchi’s Bellegra retreat, via Metropolis].

[Image: Sergio Bianchi’s Bellegra retreat, via Metropolis].

In any case, I’m posting this really just because I love the deck – in fact, I love the whole structure of this building.

I love how, as you can see in that first picture, above, there’s a small room, not quite cantilevered, elevated over an outdoor patio – and that, above that room, there’s a deck, poised under a slatted horizontal screen that allows you to watch the sky.

I also love the little walkway that extends beyond the right-hand side of the picture. The whole thing is like this maze of platforms, decks, patios, and cantilevered rooms, connected by terraces, hanging off a limestone core in the middle of the Italian countryside.

I’d like two, please.

Ground Conditions

[Image: San Francisco, photographed in profile from Sausalito].

[Image: San Francisco, photographed in profile from Sausalito].

In preparation for an overnight business trip to San Francisco this weekend, I was flipping through the Lonely Planet Guide to San Francisco – when I read something that is surely old news for anyone living in that city, but that nonetheless completely blew me away.

It turns out that part of San Francisco is actually built on the wrecked and scuttled remains of old ships.

[Image: A shipwreck that has absolutely no connection to San Francisco].

[Image: A shipwreck that has absolutely no connection to San Francisco].

The Lonely Planet guide writes that “most of this walk [through the streets near the Embarcadero] is over reclaimed land, some of it layered over the scores of sailing ships scuttled in the bay to provide landfill.”

Stunned – and absolutely fascinated by this sort of thing – I determined to learn more.

And it’s true: a good part of coastal San Francisco is not built on solid ground, but on the forgotten residue of buried ships.

In an image that makes me want to cry it’s so cool, the basements of some 19th-century San Francisco homes weren’t basements at all… they were the hulls of lost ships.

“As late as Jan 1857,” we read, “old hulks still obstructed the harbor while others had been overtaken by the bayward march of the city front and formed basements or cellars to tenements built on their decks. Even now [1888] remains of the vessels are found under the filled foundations of houses.”

In other words, when you walked downstairs to grab a jar of preserved fruit – you stepped into the remains of an old ship.

It’s almost literally unbelievable.

[Image: Another shipwreck – unrelated, as far as I’m aware, to San Francisco].

[Image: Another shipwreck – unrelated, as far as I’m aware, to San Francisco].

Best of all, those ships are still down there – and they’re still being discovered.

In the late 1960s, as San Francisco was building its BART subway system, discoveries of ships and ship fragments occurred regularly. Over the following decades, ships and pieces of ships appeared during several major construction projects along the shore. As recently as 1994, construction workers digging a tunnel found a 200-foot-long (61-meter) ship 35 feet (11 meters) underground. Rather than attempt to remove the ship – which would have been both costly and dangerous – they simply tunneled right through it. When buried ships are found, they’re sometimes looted for bottles, coins, and other valuable antiques frequently found inside. Among the prizes found in the ships have been intact, sealed bottles of champagne and whiskey, nautical equipment, and a variety of personal effects from the passengers and crews.

I’m just waiting for some rare and world-destroying virus to be found, festering away in the subterranean hold of an abandoned schooner, forgotten by city historians…

Some random cable guy discovers it, digging down into someone’s backyard to fix a transmission problem. His shovel cracks through the outer wooden shell of a 19th-century frigate, releasing a cloud of invisible bacteria… he inhales it… his brain begins to bleed… Eli Roth directs the film version.

But this also reminds me of the now classic film Quatermass and the Pit – a movie which genuinely needs to be remade, and I would gladly serve as a screenplay consultant – in which London Tube excavations uncover a buried spaceship… out of which emerge weird aliens intent on vanquishing the Queen’s English. Or something like that.

But the question remains: do you really know what’s beneath your house or apartment…?

An entire armada of lost fishing ships, now rotting in the mud, nameless and undiscovered, shivering with every earthquake.

If these reefs are islands

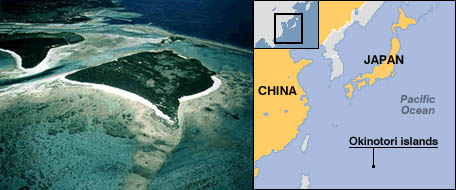

[Images: Japan’s Okinotori Islands, via the BBC, next to an unrelated image of a different reef; all reef images used in this post are from different locations].

[Images: Japan’s Okinotori Islands, via the BBC, next to an unrelated image of a different reef; all reef images used in this post are from different locations].

The BBC recently revisited the story of why Japan is now growing coral reefs in a bid to extend their territorial sovereignty into the Philippine Sea.

Successfully transplanting and cultivating these reefs would, in theory, allow Japan “to protect an exclusive economic zone off its coast”—expanding Japanese maritime power more than 1,000 miles south of Tokyo.

According to the Law of the Sea, Japan can lay exclusive claim to the natural resources 370km (230 miles) from its shores. So, if these outcrops are Japanese islands, the exclusive economic zone stretches far further from the coast of the main islands of Japan then it would do otherwise. To bolster Tokyo’s claim, officials have posted a large metal address plaque on one of them making clear they are Japanese. They have also built a lighthouse nearby.

However, the major geopolitical question remains: are these reefs truly islands?

At the moment, the Okinotori Islands (as they’re called) are merely “rocky outcrops”; but, by artificially enhancing their landmass through reefs—using reef “seeds” and “eggs”—Japan can create sovereign territory.

At the moment, the Okinotori Islands (as they’re called) are merely “rocky outcrops”; but, by artificially enhancing their landmass through reefs—using reef “seeds” and “eggs”—Japan can create sovereign territory.

This means that they’ll win economic control over all the minerals, oil, fish, natural gas, etc. etc., located in the area—providing friendly sea routes for American military ships in the process.

The U.S., of course, thinks that Japan’s sovereign reefs are a great idea; China, unsurprisingly, thinks the whole thing sucks.

In fact, we read:

Chinese interest in Okinotori lies in its location: along the route U.S. warships would likely take from bases in Guam in the event of a confrontation over Taiwan. China’s efforts to map the sea bottom, apparently so its submarines could intercept U.S. aircraft carriers in a crisis, have drawn sharp protests from Japan that China is violating its EEZ.

Which means that these artificial encrustations of living matter, planted for political reasons at the beginning of the 21st century, could very well influence the future outcome of marine combat between the United States and China.

A tiny bit more information about all this is available at the Times.

So the rest of this story could go in any number of directions:

So the rest of this story could go in any number of directions:

1) A speculative survey of other “rocky outcrops” and manmade reefs, to see who might be able to claim them and why. For instance, if Japan’s reef-based territorial ambitions are successful, could this establish a legal precedent for other such experimental terrains?

Or perhaps it could mean that the U.S. will turn away from Treasury-depleting global military adventurism to spend money on more interesting projects within its own borders—funding a whole new series of Hawaiian islands, designed by Thom Mayne, that would extend Hawaii archipelagically toward Asia…

Greece, inspired, would then expand the Cyclades with a cluster of designer islands, slowly growing to dominate the Mediterranean once again—a kind of inverse-Odyssey in which the islands themselves do all the traveling…

Or maybe there’ll be a whole new terrestrial future in store for Scotland’s Outer Hebrides, or for the Isle of Man, or for Friesland—or perhaps even a whole new Nova Scotia, extending hundreds of nautical miles into the waters of the north Atlantic, a distant, fog-shrouded world of melancholic introspection, visited by poets…

2) It’s worth remembering that the possession of land and territory has not always been a recognized marker of political sovereignty—so the Earth, in the sense of geophysical terrain, is here being swept up into a model of human governance that has only existed for a few hundred years, and which may only exist for a few decades more. So, under a different political system, these artificial reefs would be quite literally meaningless.

3) The generation of new territory for the purpose of extending—or consolidating—political power is nothing new. As but one example, I happen to be reading The Conquest of Nature: Water, Landscape, and the Making of Modern Germany, a book that “tells the story of how Germans transformed their landscape over the last 250 years by reclaiming marsh and fen, draining moors, straightening rivers, and building dams in the high valleys.”

The relevance of this here, in the context of artificial Japanese reefs in the south Pacific, is that Frederick the Great used hydrological reclamation projects—i.e. marsh draining and river redirection—literally to create new territory; this expanded the political reach of Prussia by generating more Earth upon which German-speaking settlers could then build farms and villages. All in all, this was a process of both “agricultural improvement and internal colonization,” and it “increasingly assumed the character of a military operation.”

As David Blackbourn, the book’s author, further notes: “External conquests created additional territory on which to make internal conquests, spaces on the map out of which new land could be made.” Indeed: “For Prussia, a state that was expanding through military conquest across the swampy North European plain, borders and reclamation went together.”

4) Finally, last week New Scientist ran a whole bunch of little articles called “The last place on Earth…” In each case, that leading phrase was followed by a subheading, such as: “…to be discovered,” or “…where no explorer has set foot.”

Another of those articles was: “…to be unclaimed by any nation.”

As the magazine comments in that piece: “States will go to great lengths to secure territorial claims over what appear to be worthless pieces of land.” After all, “owning even a remote rock can significantly extend a nation’s access to marine resources such as oil and fish.”

But those “great lengths” to which the nations of tomorrow may someday go could include the outright geo-architectural construction of whole new landmasses, islands, and offshore microcontinents. These terrains will be governed by Kurtzian technocrats, with iron fists, whose unchecked cruelty will inspire the literary classics of the 22nd century…

In any case, all of these points seem to imply that architects may need to brush up on their marine geotechnical skills—as well as on the legal issues surrounding the archipelagic future of political sovereignty.