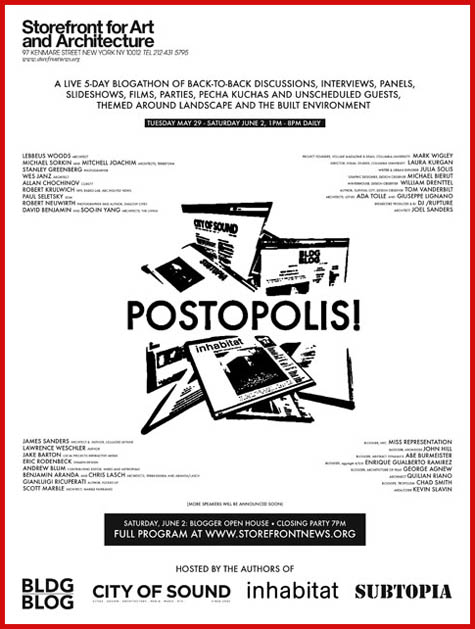

A poster for Postopolis! will be coming out soon (without a red border), including the list of speakers as it now stands – and I’m unbelievably excited about this thing. I really can’t wait.

A poster for Postopolis! will be coming out soon (without a red border), including the list of speakers as it now stands – and I’m unbelievably excited about this thing. I really can’t wait.

So: scattered over the course of five days, from May 29 to June 2, from 1pm-8pm everyday, at the Storefront for Art and Architecture in New York City, you’ll be hearing from, among many others yet to be announced:

Lebbeus Woods, Laura Kurgan, Michael Sorkin & Mitchell Joachim, Stanley Greenberg, Joel Sanders, Susan Szenasy, DJ /rupture, Andrew Blum, Jake Barton, William Drenttel, Tom Vanderbilt, Michael Bierut, Lawrence Weschler, Robert Krulwich, Benjamin Aranda & Chris Lasch, Randi Greenberg, Allan Chochinov, Julia Solis, Ada Tolla & Giuseppe Lignano, Scott Marble, Paul Seletsky, Robert Neuwirth, Wes Janz, James Sanders, Eric Rodenbeck, Kevin Slavin, Gianluigi Ricuperati, Quilian Riano, Miss Representation, Enrique Gualberto Ramirez, George Agnew, Chad Smith, Abe Burmeister, John Hill… and a lot more to come (including unannounced guests who just happen to be in New York that week).

So it should be a blast.

Stay tuned for specific times and so on, coming soon – and if you’re anywhere near NY, please consider stopping by: it’s not an academic conference, and the more people the merrier…

Finally, the other three blogs involved in planning all this are City of Sound, Inhabitat, and Subtopia – with the indispensible help of Joseph Grima, from the Storefront for Art and Architecture.

Sci-Fi Mecca

So it looks like Wired liked our science fiction and film panel, held last week.

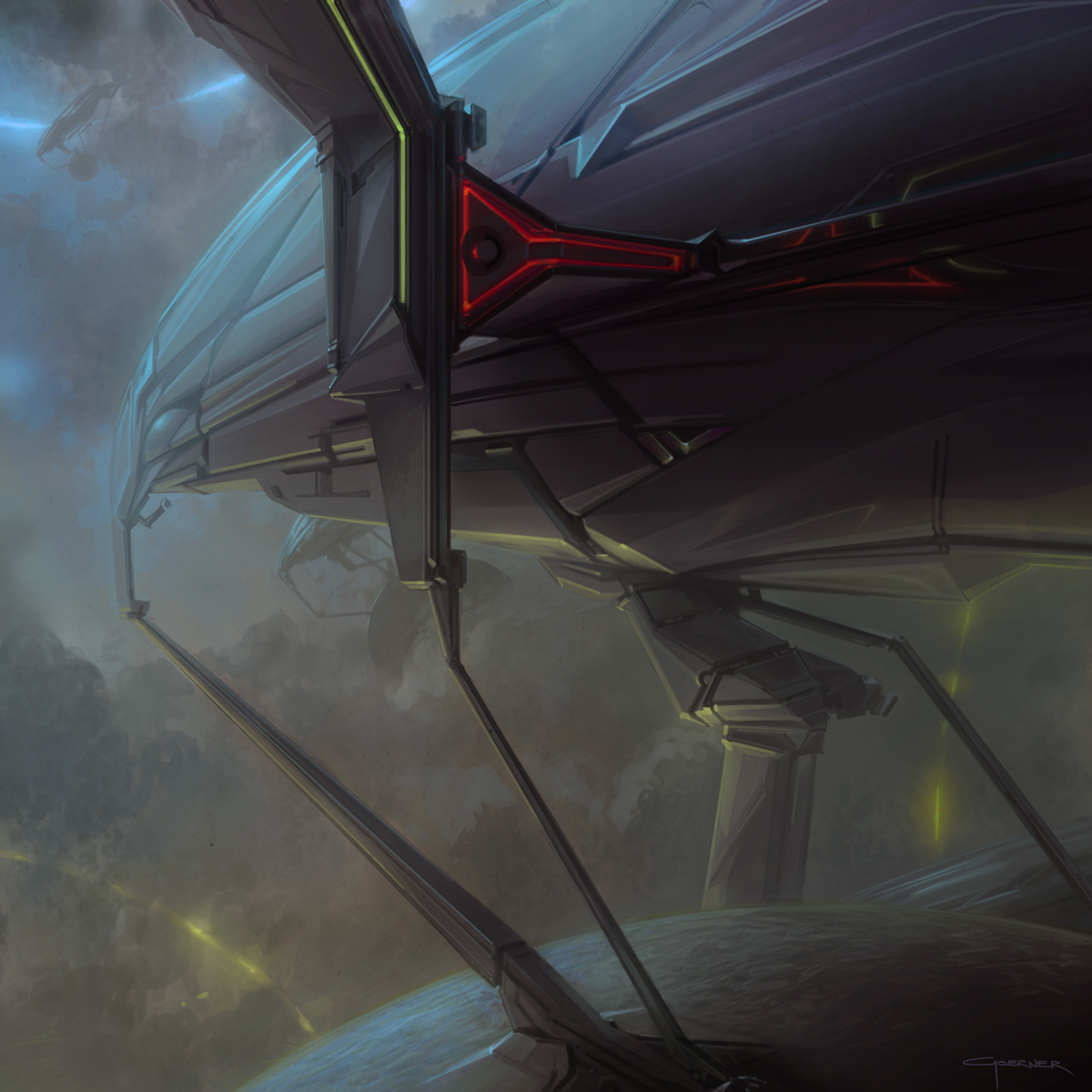

[Image: Courtesy of Mark Goerner – here’s a large version].

[Image: Courtesy of Mark Goerner – here’s a large version].

The four panelists, Wired writes, showed “art that’s rarely seen outside the film studio: pictures of otherworldy and futuristic cities that special effects crews and CGI geeks use as blueprints to build the backdrops for outer-space fights, alien worlds and castles fit for dragons.”

Read more – and see a lot more images – at Wired.

Meanwhile, some more background on the event can be found here, on BLDGBLOG – or you can even check out ARCHITECT Magazine‘s coverage of the event (although, if you read that article, note that the date for our second screening has been moved from May 9 to May 22).

Finally, if you were there, thanks again for coming out!

The Space of the Bachelor

While researching another post I hope to write soon, about Franz Kafka and a small room in San Francisco, I stumbled upon something else that seemed worth putting up on the blog; it’s from Kafka’s Diaries: 1910-1923.

In an early entry, from 1911, Kafka describes the “unhappiness of the bachelor,” an unhappiness that, for him, seems less dependent on loneliness or personal abandonment – or even on some catastrophic sense of being overlooked by the world, always – than on space: a bachelor never has enough of it.

A bachelor is alone, after all, which means that “so much the smaller a space is considered sufficient for him.”

A bachelor is alone, after all, which means that “so much the smaller a space is considered sufficient for him.”

One could perhaps say that, for Kafka, a bachelor is never spatially respected…

In any case, looking for space – or for the proper space, the one that feels right and “has a few panes of glass between itself and the night” – our bachelor finds that he “moves incessantly, but with predictable regularity, from one apartment to another.”

This goes on – and on – for the rest of his isolated existence until “he, this bachelor, still in the midst of life, apparently of his own free will resigns himself to an ever smaller space, and when he dies the coffin is exactly right for him.”

An Island for Destroyed Cities

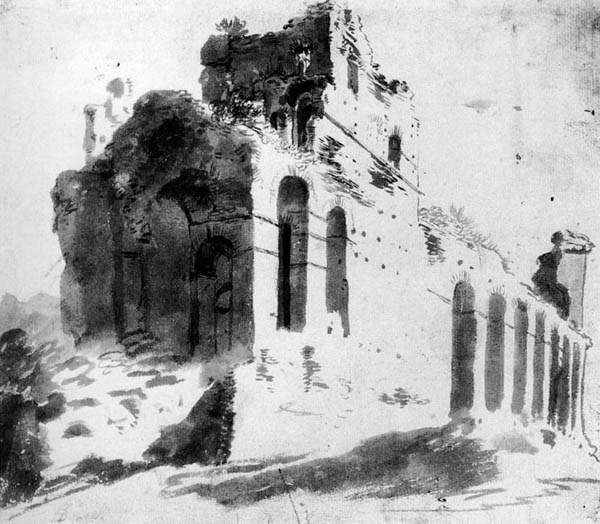

[Image: Ruins of the City Walls (1625-1627) by Bartholomeus Breenbergh].

[Image: Ruins of the City Walls (1625-1627) by Bartholomeus Breenbergh].

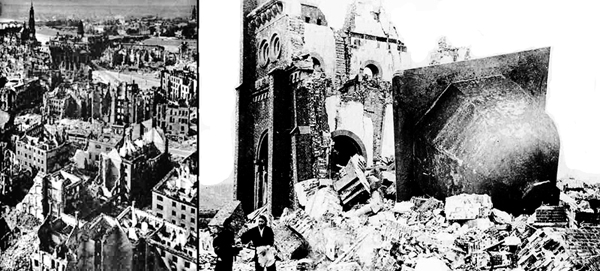

In The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War, Robert Bevan describes, in almost numbing detail, how specific buildings – indeed, whole cities – have been targeted, damaged, or otherwise destroyed by war.

He writes of the “violent destruction of buildings for other than pragmatic reasons,” claiming that “there has always been [a] war against architecture.” This war is fought through the deliberate “eradication” of an enemy’s built environment – that is, “the active and often systematic destruction of particular building types or architectural traditions.”

Some of Bevan’s examples, however, sound less like warfare than a kind of highly complex – and extremely violent – architectural ritual, played out over centuries between rival governments and religions. This is the “repeated demolition or adaptation of each other’s buildings,” and retaliation can sometimes take generations.

For instance, Bevan writes about the site of the cathedral, in Córdoba, Spain, which “started out as a Roman temple” before being destroyed by Christian Visigoths:

A subsequent church on the site was replaced by a mosque following the Arab conquest of the early eighth century. Some seventy years later this was itself demolished to create the first stage of a massive new mosque. The Christian recaptured Córdoba in 1236 and consecrated the building as a cathedral. (…) It is said that the mosque’s lamps were melted down to make new bells for the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, 800 km to the north. This probably seemed only fair, since the lamps had themselves been made from Santiago’s original bells: when the Moors had conquered the city in 997 they had dragged the bells to Córdoba and melted them down into lamps.

Tit for tat.

Bevan also describes how the Bastille, having been stormed in 1789, was reduced to a heap of stones – but these stones were then “broken up and sold as souvenirs,” in a “commodification process repeated with the fragments of the Berlin Wall 200 years later.”

In any case, Bevan goes on to discuss mosques bulldozed in the Balkans, synagogues burnt to the ground in both Poland and Germany, Armenian monasteries reduced to foundation stones as, even today, they are dismantled and reused to build houses in eastern Turkey, the dynamiting of Loyalist mansions by Irish Republican militias, the destruction of the World Trade Center, and even archaeological sites fatally disturbed during the invasion of Iraq – among many, many other such examples, all found throughout Bevan’s book.

These are all, he says, “crimes against architecture.”

More to the point here, when Bevan points out that “the bulldozed remains of the Aladza mosque” were “dumped” by Serbian troops into a nearby river – the ruins were only “identified by the mosque’s distinctive stone columns” – it occurred to me that fragments like these must be numerous enough that you could use them to reassemble complete buildings elsewhere.

More to the point here, when Bevan points out that “the bulldozed remains of the Aladza mosque” were “dumped” by Serbian troops into a nearby river – the ruins were only “identified by the mosque’s distinctive stone columns” – it occurred to me that fragments like these must be numerous enough that you could use them to reassemble complete buildings elsewhere.

You could construct a whole city from fragments of buildings destroyed by war.

For instance, all the gravel, dirt, and foundation stones from ruined buildings and cities around the world could be dropped into shallow waters off the western coast of Greece – forming the base of an artificial island, as large as Manhattan, on which to build your memorial to cities and spaces killed by war…

For instance, all the gravel, dirt, and foundation stones from ruined buildings and cities around the world could be dropped into shallow waters off the western coast of Greece – forming the base of an artificial island, as large as Manhattan, on which to build your memorial to cities and spaces killed by war…

You draw up plans with a local architecture school, plotting a whole new island metropolis constructed from nothing but pre-existing pieces of annihilated architecture – fitting arches with arches and floors with floors.

Within a decade you’ve covered the island in a maze of Chicago tenement housing, Russian churches, Indian temples, and Chinese hutongs; there are Aztec walls and pillars standing inside reconstructed Romanian state houses – before most of pre-WWII Europe begins to appear, together with shattered castles, north African villages, and the weathered masonry of pre-Columbian South America, all the buildings merging one into one another, indistinct, with Mayan rocks and Kurdish roofing joined together atop bricks from Köln and Dresden.

Another decade later and the island-city is complete. There are no cars and no electricity – in fact, no one lives there at all. It sits alone in the waters, covered in wild herbs and home to songbirds, casting shadows on itself, eroding a bit in the occasional rainstorm.

Documentaries about it soon appear on CNN and the BBC.

Only 10 people are allowed on the island at any given time; most of them just take photographs or make sketches, or write letters to loved ones, as they wander, awe-struck, through the narrow streets of this barely remembered desolation, stumbling upon extinct building types and lost statuary – towers of churches destroyed by bombs – hardly even able to conceive how all these places could have been destroyed by human conflict.

They then brush the dust of structures off their shoes as they board the boat to go home, silent, looking back at this island, the sun setting a brilliant orange behind its almost pitch-black silhouette.

Tokyo Revelation

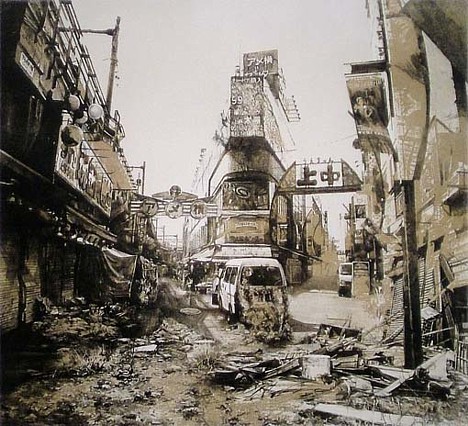

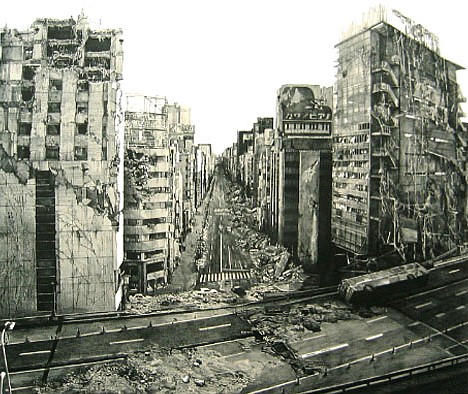

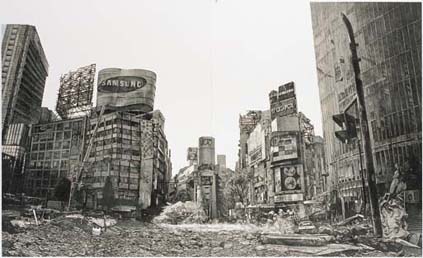

[Image: Ameyoko by Hisaharu Motoda; via Pink Tentacle].

[Image: Ameyoko by Hisaharu Motoda; via Pink Tentacle].

On Wired today, we read that “Japanese photographer Hisaharu Motada [sic] envisions the radioactive and decomposing cityscapes of post-apocalyptic Tokyo in his Neo-Ruins series of photographs.”

[Image: Ginza Chuo Dori by Hisaharu Motoda; via Pink Tentacle].

[Image: Ginza Chuo Dori by Hisaharu Motoda; via Pink Tentacle].

From Motoda’s own website:

In his Neo-Ruins series Motoda depicts a post-apocalyptic Tokyo, where familiar landscapes in the central districts of Ginza, Shibuya, and Asakusa are reduced to ruins and the streets eerily devoid of humans. The weeds that have sprouted from the fissures in the ground seem to be the only living organisms. “In Neo-Ruins I wanted to capture both a sense of the world’s past and of the world’s future,” he explains.

The resulting images are actually lithographs, heavily textured, like aged prints.

[Images: Kabukicho, Shibuya Center Town, and Electric City by Hisaharu Motoda].

[Images: Kabukicho, Shibuya Center Town, and Electric City by Hisaharu Motoda].

Of course, Motoda’s website hosts a number of other works, including this awesome image of Hashima, or Gunkanjima Island, the wonderfully creepy abandoned former mining island off the coast of Japan.

[Image: Hashima by Hisaharu Motoda].

[Image: Hashima by Hisaharu Motoda].

So who’s up for making lithographs of a post-apocalyptic Cairo…? Or Chicago, or Mumbai? I’ll write the wall-text.

(Also found via Pink Tentacle).

Science Fiction and the City: Film Fest Recap

The event last night was a blast, and so I want to thank everyone for coming out, especially the four panelists, Ryan Church, James Clyne, Mark Goerner, and Ben Procter; but I also want to thank Leslie Marcus, from the Art Center College of Design; Kyle Maynard, for his technical assistance; my wife, for photographing the whole thing; Scott Robertson, for putting me in touch with the panelists in the first place; and Jenna Didier & Oliver Hess of Materials & Applications, for helping put this whole event together.

[Images: The event, photographed by Nicola Twilley. From left to right, top to bottom, you’re seeing the Wind Tunnel itself; BLDGBLOG introducing the speakers; Mark Goerner and James Clyne; the audience; Ben Procter; some of Ben’s concept art for Superman Returns; Ryan Church, Mark Goerner, and James Clyne; Ben Procter presenting while Ryan Chuch looks on (two images); and Ryan Church presenting some of his concept art for Star Wars II: Attack of the Clones, with Ben Procter and Mark Goerner visible either side].

[Images: The event, photographed by Nicola Twilley. From left to right, top to bottom, you’re seeing the Wind Tunnel itself; BLDGBLOG introducing the speakers; Mark Goerner and James Clyne; the audience; Ben Procter; some of Ben’s concept art for Superman Returns; Ryan Church, Mark Goerner, and James Clyne; Ben Procter presenting while Ryan Chuch looks on (two images); and Ryan Church presenting some of his concept art for Star Wars II: Attack of the Clones, with Ben Procter and Mark Goerner visible either side].

There were some slips here and there – including nearly ten seconds of awesomely explosive feedback that put Merzbow to shame – and the Q&A period at the end barely got off the ground before we had to move on to screening the films; but I was really excited to see a full house – Wired magazine was even there – and to get a look at so many truly awesome works of concept art, from impossible structures and fantasy buildings to hybridized cities and a planet made from bridges – not to mention surreal juxtapositions of Czech cubism, military aerodynamism, automotive design, origami, Hieronymous Bosch, High Gothic machine-towers, and “what the Roman empire would have looked like if it had had structural steel.”

It was also great just to meet the panelists themselves, finally, and to have contributed at least a tiny bit to the beginnings of a much larger conversation about film, science fiction, and architecture.

With any luck, then, there will be another event of the same nature soon – or possibly a web feature here on BLDGBLOG – so we can continue what we started: to look at more of this stuff, and to ask these guys more questions, and maybe even to find out what it means that architecture students, for instance, know all about Archigram and Piranesi and the Pamphlet Architecture series, and they know all about paper architects from Boullée to Lebbeus Woods, but so many genuinely exciting architectural ideas – from science fiction films and the background of Hollywood blockbusters – are only casually, if ever, discussed.

As it is, the canon of accepted architectural history excludes this stuff – for no real reason. Unless it’s Metropolis or maybe Jacques Tati. But architects should be watching Minority Report as much as they read Charles Jencks or even Rem Koolhaas.

In any case, I thought the event was fun, though I apologize for the wild bursts of feedback and for the 5-minute delay in starting – but I’m glad you came out, if you did, and I hope you had a good time. And if you found the conversation cut too short at the end – as I did – then feel free to say what you wished had been said at the time, here in the comments.

Otherwise, watch out for a follow-up event/interview/feature at some point this summer.

Finally, thanks to the filmmakers who we featured last night. If you liked Bradford Watson’s 2x4x96, in particular, here’s more information, including how to contact Bradford himself; and if my description of Thorsten Fleisch’s movie using crystals grown directly on film – or geology turned into cinema – here it is.

Next up: May 22nd, 8-10pm, in the same converted Wind Tunnel in Pasadena, nearly two hours’ worth of short films about architecture, also brought to you by BLDGBLOG and Materials & Applications…

Stay tuned.

The Film Fest Cometh!

More information about the event and a gigantic version of this poster are both available…

More information about the event and a gigantic version of this poster are both available…

No RSVP is required; street parking should be ample; the building looks like this; it can be found here; 8:00pm is the starting point; and, if you show up, you’ll hear concept artists Ryan Church, James Clyne, Mark Goerner, and Ben Procter all discussing film, space, science fiction, and architecture. The films will be screened at the end.

Hope to see you there!

Meanwhile, a second night, entirely devoted to films about architecture, landscape, and the city, is still to come – once that date is finalized, we’ll have another announcement.

(Image in poster by James Clyne; for more images, by all four artists, don’t miss the film fest Flickr page).

Great streets, campuses, and pedestrian nostalgia

[Image: A street in Central Park, via Wikipedia].

[Image: A street in Central Park, via Wikipedia].

I went to an event the other night about “great streets,” held in a small theater on Venice Boulevard, in Los Angeles, about six blocks from my apartment. I walked there.

The point of the event was apparently:

1) To discuss the importance of greening the public realm… to make our communities inherently more walkable

2) To identify the most effective methods for funding these projects

3) To better understand the bureaucratic obstacles to creating more environmentally sustainable streets & sidewalks

There was also a fourth purpose: to figure out how urban space can accomodate “bikes, cars, pedestrians, flora & fauna, watershed management, open space, street vendors, retail, recreation & relaxation, [and] transit.”

All of which sounds like a great event to me, with an awesome purpose, coming at an interesting time for urban planning; but the conversation almost immediately turned into something far stranger and infinitely less important – because the moderator turned the whole thing into a kind of “what’s your favorite street in LA?” quiz.

Without going further into why that bothered me – such as the rather obvious fact that an event about “great streets” really has nothing at all to do with “your favorite street in LA,” which both narrows the topic and makes everyone waste time thinking about how they can out-cool one another, coming up with more and more obscure streets that only they have the poetic sense to celebrate – I just want to point out a few quick things.

First of all, I think it was only mentioned twice that a street can be anything other than infrastructure devoted to automotive transport – in other words, “streets” inherently just mean space for cars.

For instance, the moderator reversed his own question at one point and asked: “What’s your least favorite street in LA?” And he explained himself by adding something like: “You know, a street you get irritated on while driving.”

The whole thing was about cars.

Not only did this totally contradict the way the event pitched itself – after all, it should have been billed as a public conversation in which you get to listen to strangers explaining what streets in LA they like to drive on and why (thus attracting a totally different audience) – but it missed so many opportunities in which to talk about great streets.

After all, it was an event about great streets.

Something that become immediately clear, for instance, was that no one’s favorite street was a pedestrian-only walkway through New York City’s Central Park, or, say, Pearl Street in Boulder, Colorado (of course, neither of those are in LA – further demonstrating the weird absurdity of limiting a conversation about “great streets” to “cool drives across Los Angeles”).

For that matter, no one mentioned that their favorite street was a walking path on the campus of UCLA or Oxford.

But that’s because people seem to hear the word “street” and they immediately assume it means cars – a “street” means infrastructure for the near-exclusive use of trucks and automobiles.

A street means something I can drive my car on.

In fact, something I think about more and more lately is the possibility that Americans get as nostalgic as they do about college – identifying themselves as graduates of certain universities to a degree, and with a passion, that I genuinely think is alien to most cultures – whatever that means – not simply because college represents the only four years in which they might have pursued their real interests, but because, in the United States, college is a totally different lifestyle.

In fact, something I think about more and more lately is the possibility that Americans get as nostalgic as they do about college – identifying themselves as graduates of certain universities to a degree, and with a passion, that I genuinely think is alien to most cultures – whatever that means – not simply because college represents the only four years in which they might have pursued their real interests, but because, in the United States, college is a totally different lifestyle.

You walk everywhere.

The campus where you live and study has trees, and paths, and benches to sit on. It’s really nice. No wonder you miss it.

You can go outside and throw a football, or throw a frisbee, and you can ride a bike – and you don’t have to worry about being hit by a truck, or sprayed in the face by several pounds’ worth of carcinogens (such as car exhaust).

In other words – and this theory is transparently absurd, but I nonetheless think that its rhetorical value is such that I’ll give it space here – if you look at the particular colleges in the United States that seem to inspire the highest levels of lifelong loyalty, nostalgia, and even sports team fanaticism, you’ll find places like the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, or UCLA, or my own school, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, or even Penn State, or Georgetown – but the unifying factor there is not simply that all those schools have awesome sports teams, which they do, but that they all have really nice campuses.

So you graduate with your law degree and you move to Ft. Worth and you hang Michigan banners all over your office walls – but that nostalgic loyalty is not simply because you miss playing beer pong, it’s because you miss being able to walk around everywhere.

It’s a particularly intense form of pedestrian nostalgia.

In any case, college is like discovering a different world, tucked away inside the United States – and it’s a world that’s been built for human beings.

After all, you get at least a tiny bit of exercise everyday; you wake up, drinking coffee outside on the way to class or to work; you don’t worry about parking, or about auto theft; you see familiar people hanging out, and you can even stop off and talk to them, standing under oak trees.

You can jump around and be a total moron in your own body, outside with the friends who actually know you.

But if you do that now, commuting to work in an automobile, you get pulled over by state troopers, tasered in the face – and then you show up on Boing Boing.

It’s a different world.

It’s not a world built for you anymore. It’s a world built for cars.

In many ways, it’s as if being an adult in the United States really means changing your everyday landscape. Instead of benches, paths, people, and sunlight, you get cars, parking lots, strangers, and road rage.

If you lived in a city that looked like a college campus, you could walk to the bank; you could walk to the grocery store; you could walk to work; you could even walk to the cinema and see Spiderman 3 – and you wouldn’t have to do it alongside cars, or even crossing the paths of cars.

You’d live and work and commute on foot, walking on great streets under awesomely huge and beautiful trees – and there’d be benches to sit on, and people you know outside reading books, and you could actually understand what it means for “a day” to pass by. After all, there’s evening, and there’s mid-day, and there’s morning – and so you’d actually experience the passage of time.

You wouldn’t have to look back at the age of 35 and wonder where all that time went.

Anyway, I don’t care if you’re walking to a church or to a gun range, to a mosque or to a nightclub – the point is that you’re out there walking, feeling proud – you’re not mistaking a linked series of carcinogenic parking lots for the best your nation can do – and streets no longer have to mean cars.

Cars are awesome – I love cars, in fact I literally fantasize about owning a Toyota Tacoma. Which is a truck.

But cars are for highways, and for hauling things, and for escaping wild bear attacks. Cars are for going camping, and for driving to Baltimore because you’re bored and DC sucks.

But cars are not for everyday urban use.

If I can be permitted to go on a tiny bit longer here, let me also mention one more thing.

If I can be permitted to go on a tiny bit longer here, let me also mention one more thing.

Living out here in LA, I’m increasingly convinced that Americans simply don’t see how much paved space they’re surrounded by at any given moment.

There’s an intersection in Los Angeles, for instance, just south of Beverly Center – and it’s so ridiculously huge that I think you could fit Trafalgar Square, the Piazza San Marco, Rittenhouse Square, and, say, Berlin’s Monbijouplatz all tucked safely inside of it. In other words, it could be a pedestrian wonderland of benches and trees and places to lie out in the sun, and throw a baseball, and whatever else it is that you want to do out there under the skies of California.

Instead, it’s an intersection – and it’s one of the largest expanses of concrete I’ve ever seen.

I genuinely believe that if you measured the total square footage of that intersection alone, you’d see that at least three or four of the “great squares of Europe” would fit right in. Conversely, if you took all the piazzas, squares, parks, and plazas of Europe, and you turned them into parking lots, even a city like Bologna could look an awful lot like Los Angeles.

In any case, this week’s “great streets” event missed so many opportunities to discuss great streets as if they might be something other than just more space for automobiles – or that the open space between opposing buildings should be used for any other purpose than driving on.

There was no recognition that streets can be places to walk, or bike, or jog, or hang out with your kids, or flirt with foreign tourists, where you can read a book, and get a tan, and throw objects at your bestfriend so that he can catch them and throw them back at you, repeatedly, in a sportsman-like fashion – that would be a great street, too, in other words, and yet cars would be nowhere to be found.

Not even Toyota Tacomas.

As I say, finally, I’m not “anti-car” – despite that fact that we’re running out of oil.

I just don’t think that cars should be even remotely convenient when it comes to personal travel within cities.

Sorry.

It was just depressing to realize that the moderator at the event the other night was obsessed with a new plan out here to turn Pico and Olympic Boulevards into one-way express routes, running east and west across Los Angeles; which seemed to prove, somehow, that the infrastructure of the city should, in all cases, keep pace with car ownership.

What was genuinely never discussed, though, was not the idea that we need more highways and parking lots and one-way express lanes because everyone owns a car, but that everyone owns a car because they’re surrounded by highways and parking lots and one-way express lanes.

What else are you supposed to do in that kind of landscape?

How else can you react?

In other words, the space comes first; with this many parking lots, you can’t walk anywhere.

So, even as it was announced that Los Angeles is the most polluted city in the country, and even as LA is now expanding several highways and investing what appears to be absolutely nothing in cool transportation ideas – such as pimped-out mini-buses or light rail – this event, meant as a way to discuss “the importance of greening the public realm,” so that our communities can become “inherently more walkable,” turned into a celebration of driving in Los Angeles.

Which is great – I love driving in Los Angeles. I even have a few favorite streets here.

But:

1) A “street” is not simply space devoted to automobiles. It’s a place of movement, outdoors, that connects different destinations.

2) Cities could be designed to look like college campuses, full of trees and paths and benches and interchangeable varieties of long walks between different locations – whether those locations are churches, bookstores, police stations, football stadiums, private homes, or hash bars.

3) The reason you need a car is because you’re surrounded by highways and parking lots – it’s not the other way around. City planners need to realize this.

But none of that ever came up the other night. It was a missed opportunity.

Not that I chimed in; lamely, I left the minute it ended and walked home to eat some dinner.

Postopolis!

A few months ago, I got a call from Joseph Grima, the director of New York’s legendary Storefront for Art and Architecture gallery. Joseph wanted to put together some kind of event about architecture blogs – how blogs are participating in, redefining, and sometimes even leading the architectural conversation today, on the street, in the schools, at practicing design firms, etc.

A few months ago, I got a call from Joseph Grima, the director of New York’s legendary Storefront for Art and Architecture gallery. Joseph wanted to put together some kind of event about architecture blogs – how blogs are participating in, redefining, and sometimes even leading the architectural conversation today, on the street, in the schools, at practicing design firms, etc.

If architecture blogs are now changing what people talk about in fields ranging from urban planning, public transport, landscape architecture, green design, architectural history, and even archaeoastronomy and documentary filmmaking, then surely there should be some way to celebrate that, and to mark it with a public event or exhibition?

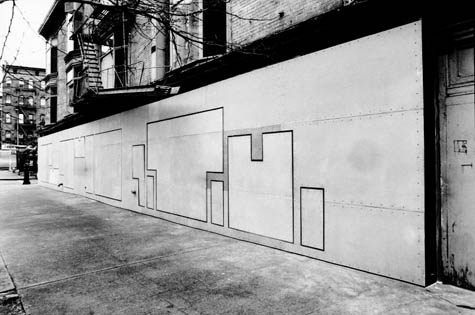

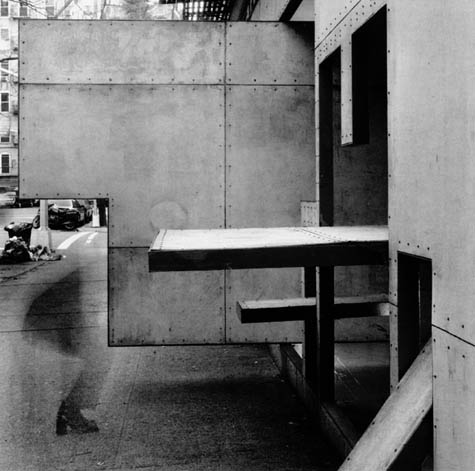

[Image: New York’s Storefront for Art and Architecture, with its famous hinged facade, designed by Steven Holl and Vito Acconci].

[Image: New York’s Storefront for Art and Architecture, with its famous hinged facade, designed by Steven Holl and Vito Acconci].

So I said yes, in an instant, then waited for things to develop – only to learn that the event would take place over five straight days of near-continuous activity, that I’d be flown all the way to New York City for it, and that Jill Fehrenbacher of Inhabitat, Bryan Finoki of Subtopia, and Dan Hill of City of Sound would also be involved (Alex Trevi of Pruned couldn’t make it).

The four of us would be given total freedom to plan whatever we wanted (provided it had at least something to do with architecture, space, landscape, and the city) – to take the same motivating energy behind our various blog posts, interviews, dialogues, plotlines, reviews, ideas, rants, histories, surveys, etc., and to recreate that in person, organizing lectures, panels, pecha kuchas, film screenings, live interviews, readings, casual mingling, wine drinking, purposeful caffeine experimentation, and maybe even some walking tours and site visits… and we’d do it at all from Tuesday, May 29, to Saturday, June 2, 2007.

The event would be called Postopolis! – exclamation point included.

[Image: The Storefront for Art and Architecture, New York City].

[Image: The Storefront for Art and Architecture, New York City].

The four of us are still in the process of assembling speakers and guests, from architects and city planners to urban explorers, military historians, novelists, and documentary filmmakers – not to mention musicians, photographers, ecologists, climate change scientists, plate tectonicists, and so on – and we’ll even be putting together an event within the event so that other architecture bloggers can join in.

After all, Postopolis! is meant to be about architecture blogs – not just about the four of us – so expanding the conversation to include as many other bloggers as possible only makes sense.

In any case, it should be awesomely and unbelievably fun – five days to talk about everything, nonstop, live from the Storefront in Manhattan.

[Image: The Storefront for Art and Architecture, New York City].

[Image: The Storefront for Art and Architecture, New York City].

More info will continue to come out on all of our blogs over the next month, so check back often – but if you’re anywhere near New York City that week, please feel free to stop by. You’ll see City of Sound, Inhabitat (check out Jill gracing the pages of Vogue this month), Subtopia, and myself, in person, with hundreds of our favorite blog posts printed out and plastered all over the walls…

Finally, thanks to Joseph Grima at the Storefront for Art and Architecture for asking us to put this together!

Finally, thanks to Joseph Grima at the Storefront for Art and Architecture for asking us to put this together!

Landscape Futures

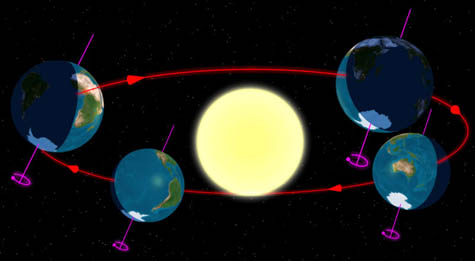

I’m increasingly fascinated by the ways in which climate change works hand in hand with, and even directly leads to, geographic change, or the physical alteration of existing landscapes.

What interests me even more, however, is the idea that landscape change can sometimes come first – a volcanic eruption, or a redirected river – sending the Earth’s climate out of wack.

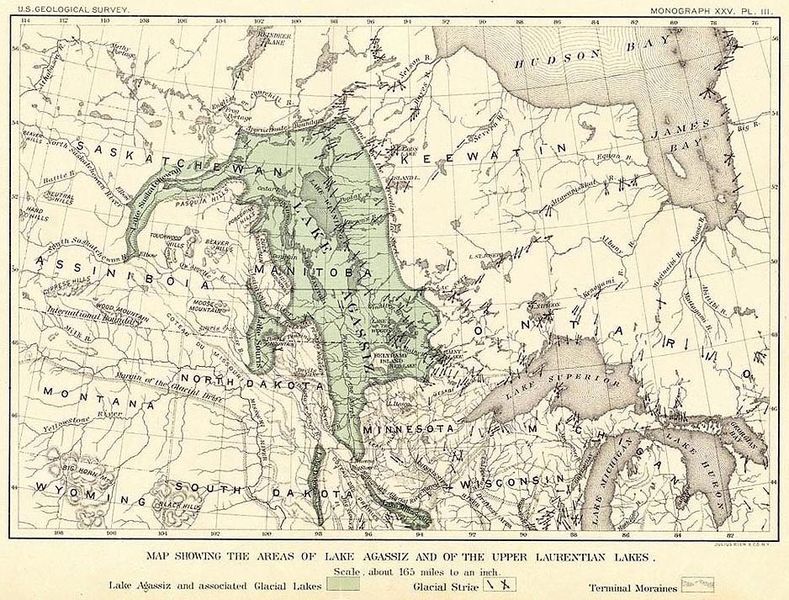

[Image: Lake Agassiz, an ancient glacial lake whose draining may have changed the global climate].

[Image: Lake Agassiz, an ancient glacial lake whose draining may have changed the global climate].

Roughly 13,000 years ago, for instance, Lake Agassiz, a gigantic freshwater lake “bigger than all of the present-day Great Lakes combined,” broke through its ice dam and flooded up the St. Lawrence Seaway, roaring directly into the Atlantic. As a result, certain oceanic currents shut down and the existing pattern of global temperatures changed in a matter of months.

Or another example: 55 million years ago, the “volcanic eruptions that created Iceland might also have triggered one of the most catastrophic episodes of global warming ever seen on Earth,” New Scientist reported last week.

In other words, the formation of Iceland was “accompanied by violent volcanic eruptions that built layers of basalt rock 7 kilometres thick.” (!) All that new rock packed “a total volume of 10,000,000 cubic kilometres, enough to build a proto-Iceland in the newly-born north Atlantic.”

In the process, though, this “huge volcanic eruption… unleashed so much greenhouse gas into the atmosphere that world temperatures rose by as much as 8°C.”

The effect “was disastrous for most life… killing off many deep-sea species.”

[Image: The completely unrelated, but nonetheless beautiful, Arenal Volcano in Costa Rica].

[Image: The completely unrelated, but nonetheless beautiful, Arenal Volcano in Costa Rica].

On the other hand, these sorts of changes can obviously work both ways: climate change comes first, affecting rainfall, thus forming deserts where there were once great plains – or any variety of other global warming scenarios.

In an article in The Guardian last week, Mark Lynas explained how the Sand Hills of Nebraska were once part of a vast desert, larger than the Sahara – “an immense system of sand dunes that spread across the Great Plains from Texas in the south to the Canadian prairies in the north,” Lynas writes.

But if you overlook the existence of federal irrigation projects, and other government water subsidies, the only major difference between then and now is 1ºC.

In other words, it’s only one degree cooler today than it was when huge sand dunes roamed across North America.

Meanwhile, Lynas goes on to explore how, with every jump of only 1ºC in the average planetary temperature today, wildly different landscapes become possible around the world.

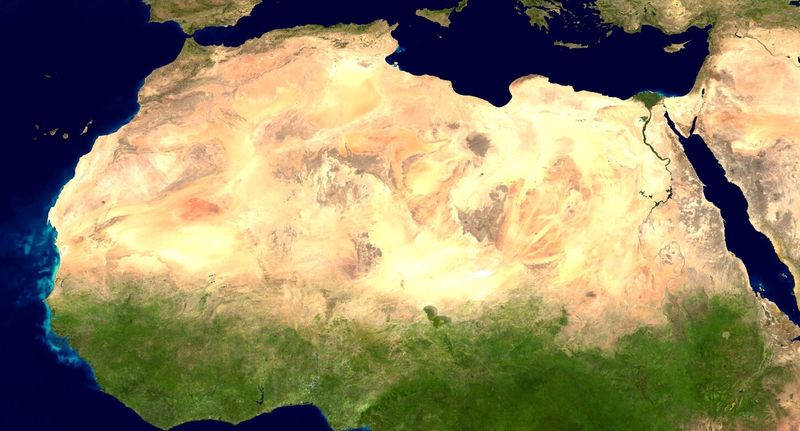

The one possibility that truly blows me away – and even makes me want to make a science fiction film, or write a graphic novel, or even publish a BLDGBLOG book of short stories set in this insane new landscape – is this: once Europe is 4ºC hotter than it is today, “new deserts will be spreading in Italy, Spain, Greece and Turkey: the Sahara will have effectively leapt the Straits of Gibraltar.”

Imagining the cities of northern Italy buried in sand – with Renaissance statuary chest-deep in dunes…

[Image: The Sahara desert, waiting to spring upon the unsuspecting streets of Paris… Via Wikipedia].

[Image: The Sahara desert, waiting to spring upon the unsuspecting streets of Paris… Via Wikipedia].

Lynas continues:

In Switzerland, summer temperatures may hit 48ºC, more reminiscent of Baghdad than Basel. The Alps will be so denuded of snow and ice that they resemble the rocky moonscapes of today’s High Atlas – glaciers will only persist on the highest peaks such as Mont Blanc. The sort of climate experienced today in Marrakech will be experienced in southern England…

And so on.

However, I don’t mean to celebrate the annihilatory effects of global climate change here; I simply mean to point out that: 1) some of these changes are deliriously surreal and, as such, they’re actually quite fun to think about; and 2) a very, very strange future awaits our descendents, should anything even remotely like this come to pass.

Actually, 3): it’s also worth pointing out that, today, a novel set in an abandoned Rome, crawling with sand dunes, would be considered a work of science fiction – but, in one hundred years’ time, such a setting may be much closer to social realism. In other words, literary genres will also be forced to adapt in an era of rapid climate change. (This same topic is actually discussed in BLDGBLOG’s forthcoming interview with novelist Kim Stanley Robinson).

Finally, all of these speculative landscapes of the future have already begun to inspire something of a new golden age for international law. The future of Canada’s “Northwest Passage” is a perfect example of this.

As ice continues to thaw throughout the Canadian Arctic, a fantastically convenient shipping route, reaching from the Atlantic through to Asia, is taking shape. This route cuts right through Canada’s sovereign terrain – but, with such huge sums of money at stake for international trade, will the Canadian government be able to maintain control over the seaway…?

The question, then, involves whether the Northwest Passage should be considered a “transit passage” – and, thus, subject to Canadian law – or an “international strait” – thus, outside of Canada’s reach.

[Image: The Northwest Passage, as imagined by Sir John Ross, 1819].

[Image: The Northwest Passage, as imagined by Sir John Ross, 1819].

According to a recent essay in the London Review of Books, “Canada claims that the passage constitutes Canadian internal waters” – but the United States, perhaps unsurprisingly, “insists that the passage is an ‘international strait’.”

However, the essay goes on to explain that treating the Passage as an international strait – which means it will be free from Canadian regulations, controls, and other legal constraints – may actually pose unexpected consequences in the realm of international security.

Anyway – etc. etc.

Basically, what I think is cool here is that large-scale terrestrial transformation in an era of rapid climate change is already beginning to impact upon fantastically mundane questions – of law, property, sovereignty, and so on – showing that no matter how sci-fi a situation may likely be, you can always find some way to fit it into human legislation.

In any case, I’m sure I’ll be returning to this topic soon.

The architecture of solar alignments

[Image: The solar-aligned ruins of Chankillo, Peru; via the BBC].

[Image: The solar-aligned ruins of Chankillo, Peru; via the BBC].

The Chankillo ruins, near the Peruvian coast, made the news a few months back when they were discovered to be an ancient solar observatory.

According to NASA, some archaeologists “have nicknamed the ruin’s central complex the ‘Norelco ruin’ based on its resemblance to a modern electric shaver.”

Just southeast of the “electric shaver,” however, are a series of structures called “the Thirteen Towers, which vaguely resemble a slightly curved spine.”

[Image: Photo by Ivan Ghezzi, demonstrating solar alignments with the “slightly curved spine” of the Thirteen Towers; via the BBC].

[Image: Photo by Ivan Ghezzi, demonstrating solar alignments with the “slightly curved spine” of the Thirteen Towers; via the BBC].

Quoting NASA:

The Thirteen Towers were the key to the scientists conclusion that the site was a solar observatory. These regularly spaced towers line up along a hill, separated by about 5 meters (16 feet). The towers are easily seen from Chankillo’s central complex, but the views of these towers from the eastern and western observing points are especially illuminating. These viewpoints are situated so that, on the winter and summer solstices, the sunrises and sunsets line up with the towers at either end of the line. Other solar events, such as the rising and setting of the Sun at the mid-points between the solstices, were aligned with different towers.

The BBC quotes a man called Clive Ruggles, professor of archaeoastronomy in Leicester, England: “These towers have been known to exist for a century or so. It seems extraordinary that nobody really recognised them for what they were for so long.”

[Image: Like some kind of machine embedded in the surface of the earth, it’s the Chankillo Observatory. Courtesy of GeoEye/SIME, via NASA’s Earth Observatory].

[Image: Like some kind of machine embedded in the surface of the earth, it’s the Chankillo Observatory. Courtesy of GeoEye/SIME, via NASA’s Earth Observatory].

For all that, though, the surrounding landscape at Chankillo is itself just extraordinary; you can’t see it in the images above, however, so take a look at this image – or even at this huge version of that image, or even at this truly gigantic (3.4mb) version.

Meanwhile, I’m a genuine sucker for solar-alignment theories involving landscapes and architecture; in fact, I was just talking to someone about this the other day.

Yet I’m even more of a sucker for unintentional examples of such things – like houses with pitched gable roofs that accidentally line-up with the sun every summer solstice…

I’ve talked about this kind of thing on BLDGBLOG before – but that doesn’t mean I won’t do it again.

For instance: one day, a science writer in her late 30s gets an email saying that she’s being sent to report on iceberg calving off the western coast of Greenland.

She takes a boat, along with some climate scientists and oceanographers, and they find themselves inside the region of study by the second week of June. Icebergs are flowing past the ship on all sides; no one can believe how many there are. Measurements are taken; the icebergs continue to drift.

The days grow longer.

[Image: Via Wikipedia].

[Image: Via Wikipedia].

Then, on the morning of the summer solstice, our science journalist can’t sleep. She’s been up all night, flipping her pillow over and back, shoving the blankets off then pulling them tight again, etc. etc.

Finally, she gets out of bed and wanders out onto the deck of the ship – where she sees the sun of the summer solstice just hanging there.

Incredibly, though, a perfect line of drifting icebergs – ten, twenty, thirty icebergs – stretches out, one after the other, toward the horizon. The effect is uncanny; it looks as if the icebergs have been deliberately placed there, sculpted into an unbroken line by unseen forces – and right above them, of course, is the summer sun, casting a reflective line of golden light from one icy peak to the next.

It’s as if, for that precise moment, from the deck of that particular ship, for that one woman alone, the Arctic seascape has been arranged to line up with the solstice.

In any case, I think there should be an ongoing competition – or at least some kind of internet archive – for photographic proof of unexpected solar alignments: four times a year, perhaps – on the solstices and equinoxes – you go out and search for weird alignments of the sun…

In a small town outside Albany, the windows of every house in one particular cul-de-sac light up, the sun shining straight through house after house, in a perfectly straight line, as if they’d been built for the purpose, a monumental solar observatory the exact size and shape of suburbia – till one family closes their curtains, and the effect is gone.

(Earth Observatory image found via del.icio.us/pruned).