[Image: A collage of various buildings by Robert Scarano, from photos by Gabrielle Plucknette for the New York Times].

[Image: A collage of various buildings by Robert Scarano, from photos by Gabrielle Plucknette for the New York Times].

After reading today that a New York appeals court has upheld a ban on architect Robert Scarano, preventing him from practicing in the city, I found this fascinating anecdote published a few months ago about one of the tactics Scarano has used to get his developments cleared by the Department of Buildings. Quoting the New York Times at length:

It’s the summer of 2008. A young couple decides to buy an 800-square-foot apartment in a new condo building on the gentrifying outer edge of a fashionable Brooklyn neighborhood. The buyers go to close on the place, and as they’re signing away half a million dollars, the building’s developer, keeping a wary eye on the hovering lawyers, leans over and whispers something. There’s a second bathroom in the apartment, he says, one that does not appear on the floor plan—its doorway is concealed behind an inconspicuous layer of drywall. At first, the buyers think the developer is kidding. This is before the crash, near the peak of the market, and no one’s giving away a square inch. But the developer says no, he’s dead serious, just look. So a few days after they buy the place, the couple takes a sledgehammer to their wall.

Like something out of House of Leaves—or a kind of architectural Advent calendar, in which various walls are knocked down at specific times of the year to reveal whole new rooms and corridors behind them—the building contained more space than its own exterior had indicated.

Later, the article’s author goes on to attend a party in another of Scarano’s buildings: “‘There’s a secret room,’ [the party’s host] told me, conspiratorially. Up on the mezzanine level, next to a pair of D.J.’s turntables, he knocked on a wall. It sounded hollow.”

I have to admit that this totally blows my mind. Imagine another room within that room whose doorway is also sealed behind drywall—and then other rooms within that room, and further corridors and stairs and entrances. Tap, tap, tap—you navigate by sound, knocking deeper and deeper into an architectural world you only reveal by means of careful deconstruction. Amidst this labyrinth of drywalled rooms, you realize the true extent of your property, which extends so far beyond what you originally thought was your building that you end up, at one point, standing in another zip code.

[Image: The underground city of Derinkuyu].

[Image: The underground city of Derinkuyu].

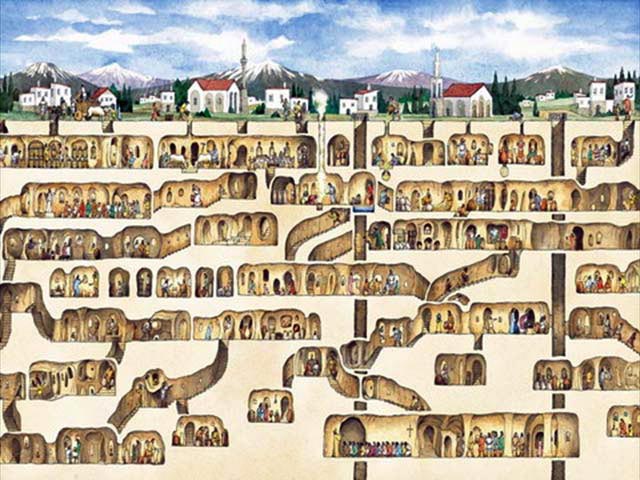

In a way, I’m reminded of the massive underground city of Derinkuyu, which, as Alan Weisman explains in The World Without Us, was discovered entirely by accident:

No one knows how many underground cities lie beneath Cappadocia. Eight have been discovered, and many smaller villages, but there are doubtless more. The biggest, Derinkuyu, wasn’t discovered until 1965, when a resident cleaning the back wall of his cave house broke through a wall and discovered behind it a room that he’d never seen, which led to still another, and another. Eventually, spelunking archeologists found a maze of connecting chambers that descended at least 18 stories and 280 feet beneath the surface, ample enough to hold 30,000 people—and much remains to be excavated. One tunnel, wide enough for three people walking abreast, connects to another underground town six miles away. Other passages suggest that at one time all of Cappadocia, above and below the ground, was linked by a hidden network. Many still use the tunnels of this ancient subway as cellar storerooms.

In any case, for Scarano it was not always about literally hiding extra rooms inside a building; it was often just a matter of using certain words—like basement—instead of others—like cellar—to hide his intentions. For instance, “Scarano tried to build a two-story addition to the roof of [an] old warehouse by transferring floor area from the building’s lowest level, which he planned to convert to parking, to the top of the roof. But the zoning code distinguished between a basement (which is partly above ground, defined as habitable, and therefore counted toward the floor-area ratio) and a cellar (which is underground and uninhabitable). Opponents accused Scarano of trying to finesse the difference, and eventually the Department of Buildings declared the space a cellar. New height limits have been established in the neighborhood, and the partly built addition is coming down.”

Or this: Scarano “adapted the zoning rules that applied to warehouse conversions. Under certain circumstances, the code classified loft mezzanines as storage space, not floor area, and Scarano assured developers their new building plans could slip through this loophole.”

It’s hermeneutics—as if the spatial expansion of whole neighborhoods is really just a graph of certain words used in different contexts. As if vocabulary itself materializes, precipitating out as alternative spatial futures for the city. Indeed, the New York Times writes, “in Scarano’s view, the city’s code was a Talmudic document, open to endless avenues of interpretation. Through a variety of arcane strategies, he could literally pull additional real estate out of the air.”

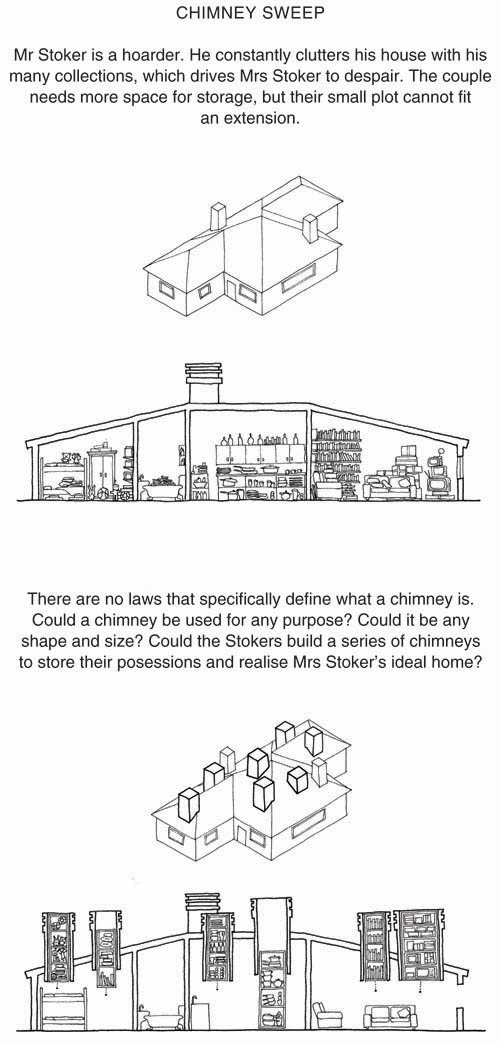

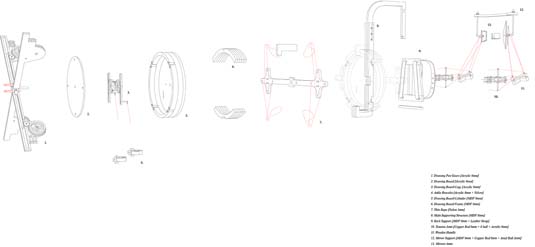

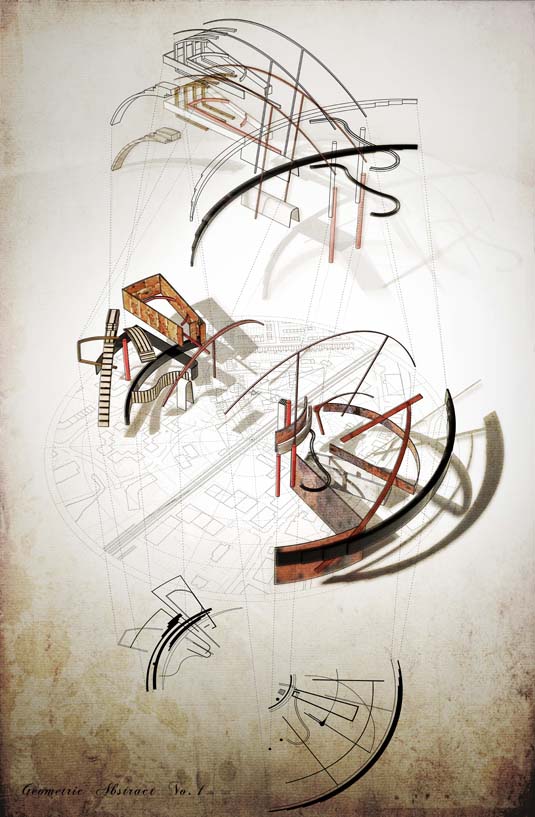

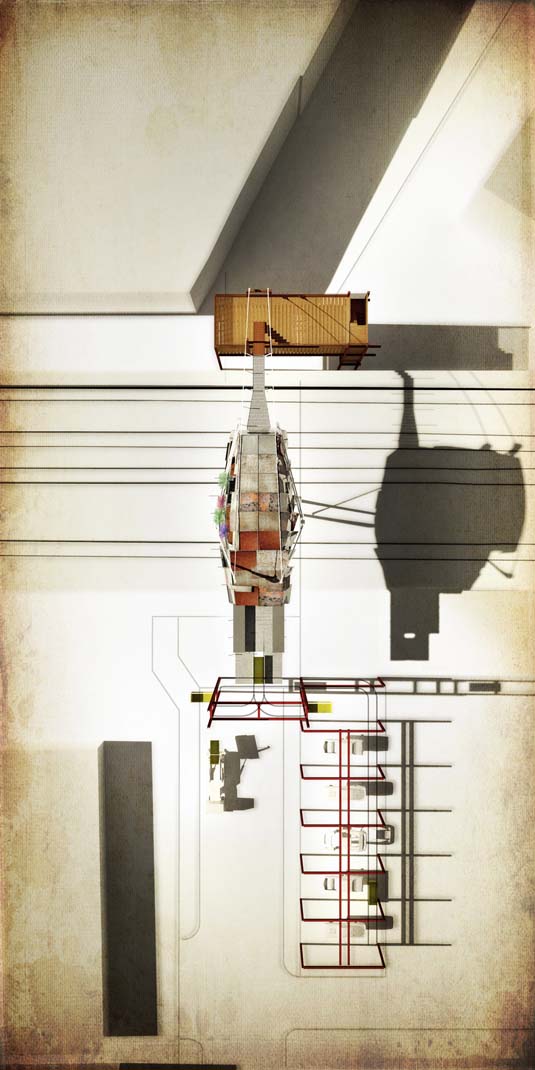

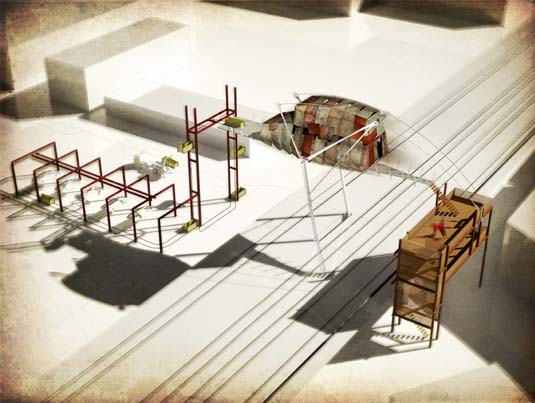

I’ve long been a fan of David Knight and Finn Williams, two London architects with an encyclopedic knowledge of that city’s building permissions and zoning codes (I highly recommend their book SUB-PLAN: A Guide to Permitted Development, as well as Knight’s recent guest post on Strange Harvest). The following image, taken from that book, is just one example of the type of interpretation-based spatiality so often abused by Scarano.

[Image: From SUB-PLAN: A Guide to Permitted Development by David Knight and Finn Williams].

[Image: From SUB-PLAN: A Guide to Permitted Development by David Knight and Finn Williams].

Whether or not hiding entire rooms behind drywall is part of London’s “permitted development” is something we’ll have to ask Knight and Williams.

(Thanks to a tip from Nicola Twilley).

[Image:

[Image:

[Image: The “

[Image: The “

[Images: The “

[Images: The “

[Images: The “

[Images: The “

[Images: The “

[Images: The “ [Images: The “

[Images: The “

[Images: The “

[Images: The “

[Image: Allied bombers in World War 2; via

[Image: Allied bombers in World War 2; via

[Image: The infrastructure of

[Image: The infrastructure of  [Image: “

[Image: “

[Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:  [Image:

[Image:

[Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

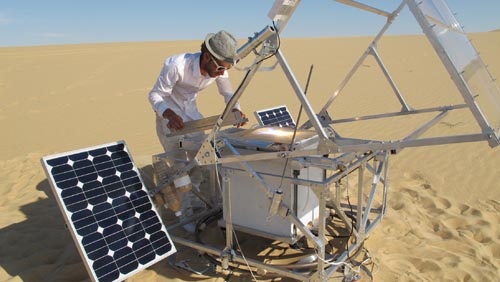

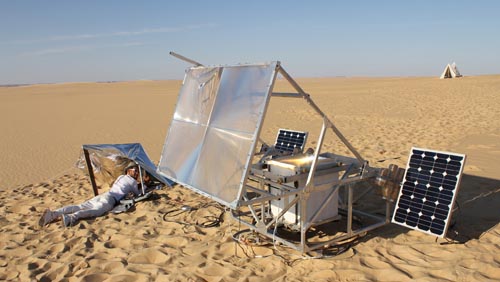

[Image:  [Image: From Armin Blasbichler’s bank robbery course; via

[Image: From Armin Blasbichler’s bank robbery course; via  [Image: From Armin Blasbichler’s bank robbery course; via

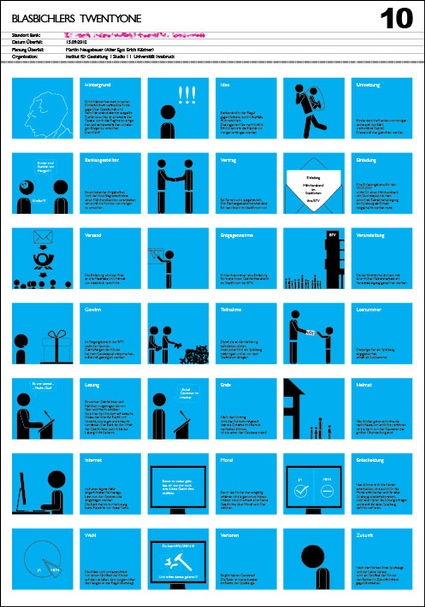

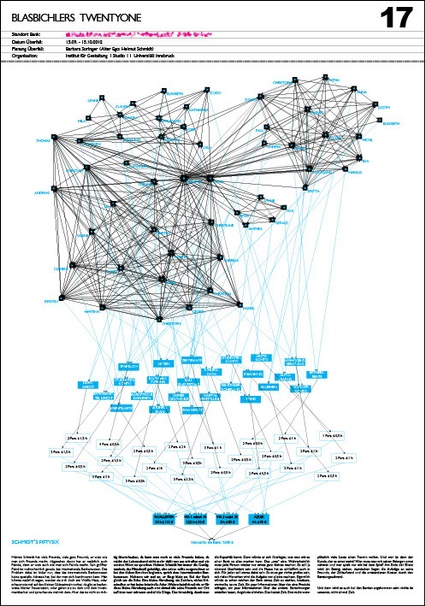

[Image: From Armin Blasbichler’s bank robbery course; via  [Image: Internet-in-a-suitcase, via the

[Image: Internet-in-a-suitcase, via the