[Image: The brick-arched entryway to a “mysterious Chinese tunnel” in the Pacific Northwest (via)].

[Image: The brick-arched entryway to a “mysterious Chinese tunnel” in the Pacific Northwest (via)].

72 years ago, a man named William Zimmerman sat down with a to tell an agent of the U.S. government to tell a story about “mysterious Chinese tunnels” beneath the Pacific Northwest. His interview was conducted as part of the Federal Writers’ Project, and it can be read online in a series of typewritten documents hosted by the Library of Congress.

Zimmerman claims that “mysterious” tunnels honeycombed the ground beneath the city of Tacoma, Washington. These would soon become known as “Shanghai tunnels,” because city dwellers were allegedly kidnapped via these underground routes – which always led west to the city’s docks – only to be shipped off to Shanghai, an impossibly exotic urban world across the ocean. There, they’d be sold into slavery.

[Image: The cover page for one of many U.S. government documents called “Mysterious Chinese Tunnels“].

[Image: The cover page for one of many U.S. government documents called “Mysterious Chinese Tunnels“].

Subterranean space here clearly exists within an interesting overlap of projections: fantasies of race, exoticism, and a subconscious fear of the underworld all wrapped up into one narrative package. White Europeans had expanded west all the way to the Pacific Ocean – only to find themselves standing in a fog-covered marsh, on earthquake-prone ground, with a “mysterious” race of Chinese dock workers tunneling toward them through the earth, looking for victims… It’s like a geography purpose-built for H.P. Lovecraft: down in the foundations of your city is a mysterious network of rooms, excavated by another race, through which unidentified strangers move at night, conspiring to abduct you.

[Image: Another “mysterious Chinese tunnel” in the Pacific Northwest (via)].

[Image: Another “mysterious Chinese tunnel” in the Pacific Northwest (via)].

In any case, because “construction of the Northern Pacific Railroad required large numbers of railroad laborers,” Zimmerman’s tale begins, “many Chinese coolies” had to be smuggled into the “rapidly growing city of Tacoma.” They “arrive[d] mysteriously,” he says, “smuggled in on ships, and even Indian canoes, from British Columbia.”

Several opium joints were known to be operating in Tacoma. And there was no question in the minds of many people that the narcotic was smuggled in through tunnels from their dens to cleverly hidden exits near the waterfront. They were also convinced that the tunnels were dug by Chinese, either as a personal enterprise or at the behest of white men of the underworld, as no white workmen would burrow the devious mole-like passageways and keep their labors secret.

Zimmerman adds that the Chinese “were forcibly expelled from Tacoma in 1885, but ever [sic] so often the story of the Chinese tunnels bobs up whenever workmen come across them in excavation work.”

[Image: Entries to Tacoma’s mysterious Chinese underworld? Photo by Stephen Cysewski (via)].

[Image: Entries to Tacoma’s mysterious Chinese underworld? Photo by Stephen Cysewski (via)].

Meanwhile, the same year as Zimmerman’s interview – 1936 – a 39-year old man named V.W. Jenkins also sat down with a representative of the Federal Writers’ Project, and he had this story to tell:

In the spring of 1935 when the City Light Department was placing electric power conduits under ground, workmen digging a trench in the alley between Pacific Avenue and ‘A’ Street at a point about 75 feet south of 7th Street, just back of the State Hotel, crosscut an old tunnel about ten feet below the surface of the ground. This tunnel was about three feet wide by five feet high, and tended in a southwesterly direction under the State Hotel, and in the opposite direction southeasterly toward Commencement Bay. I entered the tunnel and walked about 40 or 50 feet in each direction from the opening which we had encountered. There it went under the hotel the tunnel dipped sharply to pass under the concrete footings of the rear wall, proving that the tunnel was dug after the hotel had been built. In the other direction the tunnel had a sharp turn to the left, and after several feet, a gradual curve to the right, so that it was again tending in the same direction as at the opening. About 50 feet from the opening on the Bay side the tunnel began to dip and in another ten feet began to decline very sharply so that it would have been necessary to use a rope to descend safely on the met slippery floor. The brow of the bluff overlooking the waterfront is but a short distance from this point, explaining the need for the rapid downward slope, although it is probable that farther on there is a turn, either right or left, and that the tunnel was dug at an easier grade before emerging at a lower level.

Jenkins then offers this bizarrely wonderful explanation for what else might have formed those tunnels:

Some persons contend that these openings found in the vicinity of Tacoma were caused by trees buried in the glacial age, and after decaying, left the openings in the glacial drift. If this is the true explanation for the tunnel I have described, then the tree that made it must have been a giant that grow such in the shape of a corkscrew.

Of course, there are also “Shanghai tunnels” beneath Portland, Oregon. “All along the Portland waterfront,” we read, “…’Shanghai Tunnels’ ran beneath the city, allowing a hidden world to exist. These ‘catacombs’ connected to the many saloons, brothels, gambling parlors, and opium dens, which drew great numbers of men and became ideal places for the shanghaiers to find their victims. The catacombs, which ‘snaked’ their way beneath the streets of what we now call Old Town, Skidmore Fountain, and Chinatown, helped to create an infamous history that became ‘cloaked’ in myth, superstition, and fear.”

The same website linked above describes the actual process of so-called Shanghai’ing:

The victims were held captive in small brick cells or makeshift wood and tin prisons until they were sold to the sea captains. A sea captain who needed additional men to fill his crew notified the shanghaiiers that he was ready to set sail in the early-morning hours, and would purchase the men for $50 to $55 a head. ‘Knock-out drops’ were then slipped into the confined victim’s food or water.

Unconscious, they were then taken through a network of tunnels that ‘snaked’ their way under the city all the way to the waterfront. They were placed aboard ships and didn’t awake until many hours later, after they had ‘crossed the bar’ into the Pacific Ocean. It took many of these men as long as two full voyages – that’s six years – to get back to Portland.

It all sounds like some prehistoric narrative of the afterlife – a shaman’s tale of a near-death experience: you’re blacked out and led through mysterious tunnels inside the earth, only to wake up surrounded by the oceanic, on your way to another world.

This site offers quite a lot of history of the Tacoma tunnels, and ten minutes of Googling will reveal at least a dozen blog posts and assorted minor newspaper articles about the phenomenon; but there’s something particularly intriguing about an official oral history, conducted by the U.S. government, in which tales of subterranean geography are revealed. The papers have the feel of a kind of national psychoanalysis, where each session takes the form of geographic speculation. More practically, such interviews are a fantastic premise for a short novel or film.

[Image: Photo by Michael Cook. “Looking into the bottom of the William B. Rankine G.S. wheelpit from the Rankine tailrace“].

[Image: Photo by Michael Cook. “Looking into the bottom of the William B. Rankine G.S. wheelpit from the Rankine tailrace“].

Briefly, though, I’m also reminded of BLDGBLOG’s interview with Michael Cook, an urban explorer based in Toronto, posted last summer.

Toward the end of that interview, I asked Cook “if there’s some huge, mythic system out there that you’ve heard about but haven’t visited yet” – some long-rumored underworld that might only be speculation. Cook replies:

I guess the most fabled tunnel system in North America is the one that supposedly runs beneath old Victoria, British Columbia. It’s supposedly connected with Satanic activity or Masonic activity in the city, and there’s been a lot of strange stuff written about that. But no one’s found the great big Satanic system where they make all the sacrifices.

You know, these legends are really… there’s always some sort of fact behind them. How they come about and what sort of meaning they have for the community is what’s really interesting. So while I can poke fun at them, I actually appreciate their value – and, certainly, these sort of things are rumored in a lot of cities, not just Victoria. They’re in the back consciousness of a lot of cities in North America.

(With huge thanks to Alexis Madrigal, who sent me a link to the Tacoma tunnels last summer).

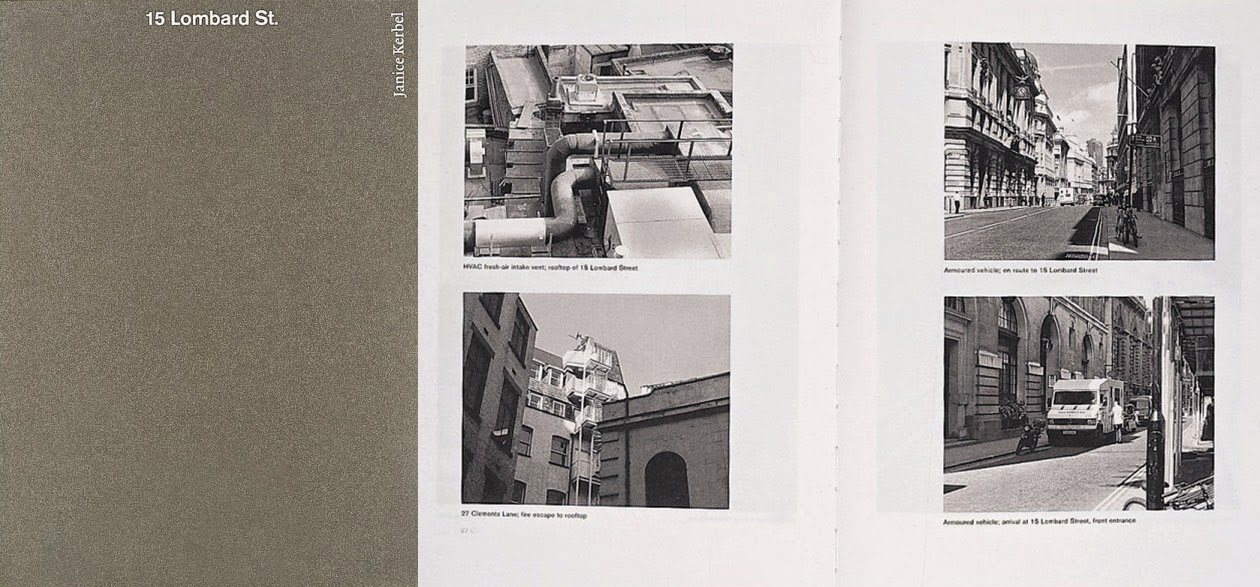

[Image: The cover and a spread from

[Image: The cover and a spread from

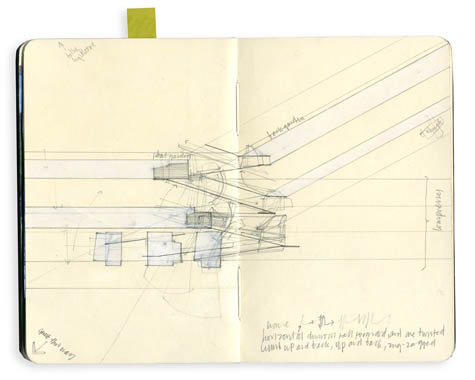

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: The brick-arched entryway to a “mysterious Chinese tunnel” in the Pacific Northwest (

[Image: The brick-arched entryway to a “mysterious Chinese tunnel” in the Pacific Northwest ( [Image: The cover page for one of many U.S. government documents called “

[Image: The cover page for one of many U.S. government documents called “ [Image: Another “mysterious Chinese tunnel” in the Pacific Northwest (

[Image: Another “mysterious Chinese tunnel” in the Pacific Northwest ( [Image: Entries to Tacoma’s mysterious Chinese underworld? Photo by Stephen Cysewski (

[Image: Entries to Tacoma’s mysterious Chinese underworld? Photo by Stephen Cysewski ( [Image: Photo by

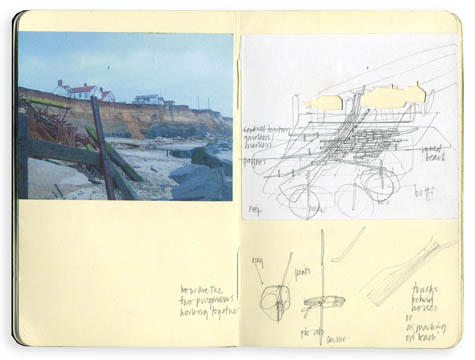

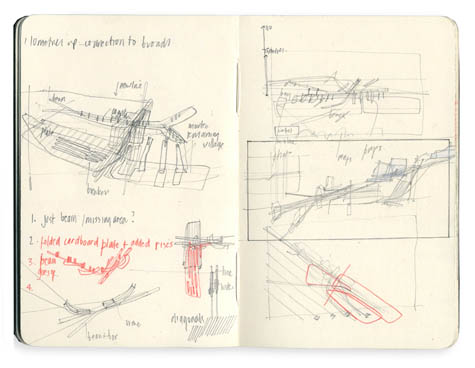

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Sketches by

[Image: Sketches by

[Images: Sketches by

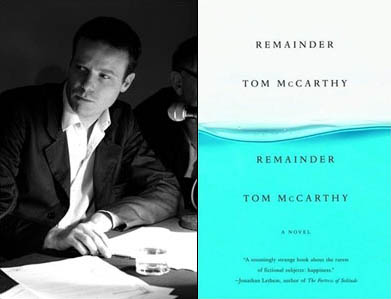

[Images: Sketches by  [Image: Tom McCarthy and

[Image: Tom McCarthy and  [Images: Poison ivy, resplendent in high-CO2 environments. Photos by Steve Legato for

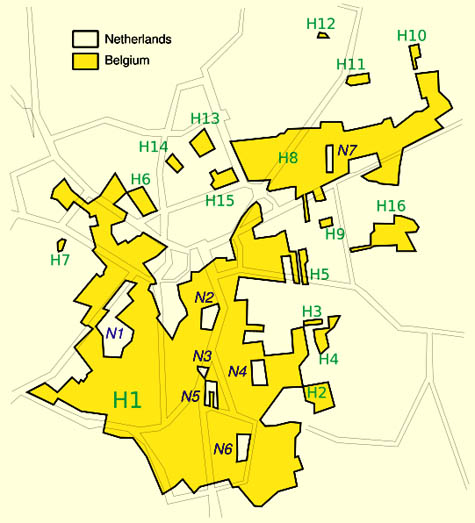

[Images: Poison ivy, resplendent in high-CO2 environments. Photos by Steve Legato for  [Image: The strange, island-like spaces of micro-sovereignty within the town of

[Image: The strange, island-like spaces of micro-sovereignty within the town of  Before we get there, though – and before I sidetrack myself pointing out that “diplomatic folklore” would be an amazingly interesting literary sub-genre – Ascherson’s paper is about the fluid nature of “international space.” He focuses particularly on the changing natures of both terrain and sovereignty – and how the definition of one always affects the definition of the other.

Before we get there, though – and before I sidetrack myself pointing out that “diplomatic folklore” would be an amazingly interesting literary sub-genre – Ascherson’s paper is about the fluid nature of “international space.” He focuses particularly on the changing natures of both terrain and sovereignty – and how the definition of one always affects the definition of the other.  [Image: BLDGBLOG speaks with

[Image: BLDGBLOG speaks with

[Images: Interviewing

[Images: Interviewing  [Image: The

[Image: The