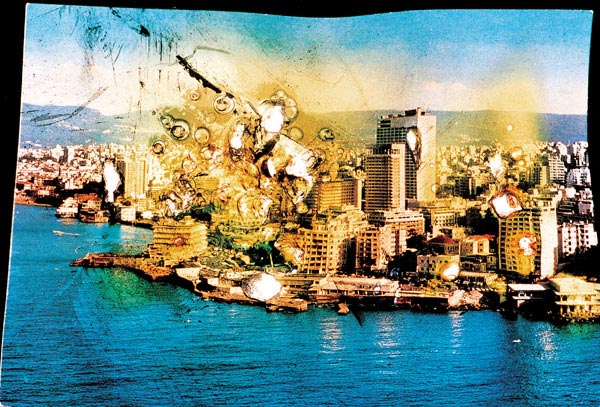

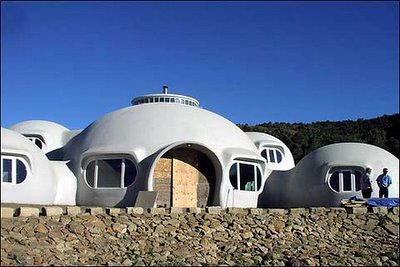

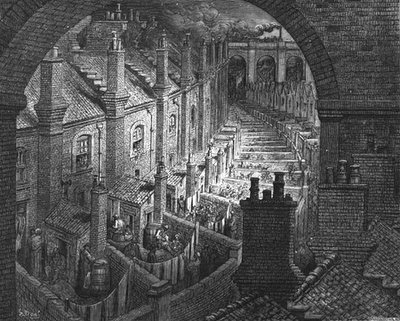

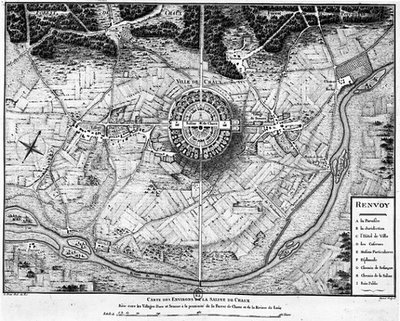

“War, however tragic, is often a source of architectural invention,” writes Farès el-Dahdah.

“Beirut’s recent civil warfare produced many such inventions,” he suggests. “Black drapes, eight stories high and hung across urban interstices shielded pedestrians from the deadly trajectory of a sniper’s view so as to veil one fighting camp from another. Shipping containers were filled with sand and arranged as divisive labyrinths along frontlines… Entering a building became an oblique experience as one was forced to slither sideways behind oil barrels filled with concrete. War is inevitably linked with architectural experience…”

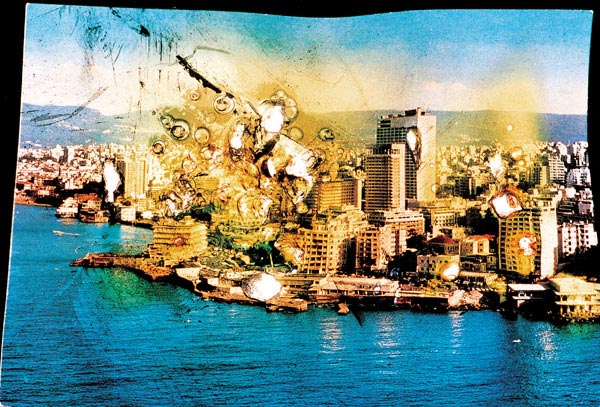

[Image: From Wonder Beirut, 1997-2004, by Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige].

[Image: From Wonder Beirut, 1997-2004, by Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige].

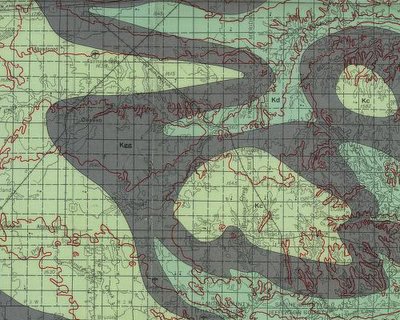

According to architect Rodolphe el-Khoury in an article for Alphabet City #6, “In Beirut’s centre-city, where the busiest and densest structures once stood, now lies an empty field… a tabula rasa at the very heart of the city. This cleared ground has no discernible physical differentiation: all traces of streets and building masses are now erased. Also obliterated are the property lines, zoning envelopes and other invisible but no less ‘real’ demarcations which customarily determine or reflect urban morphologies.”

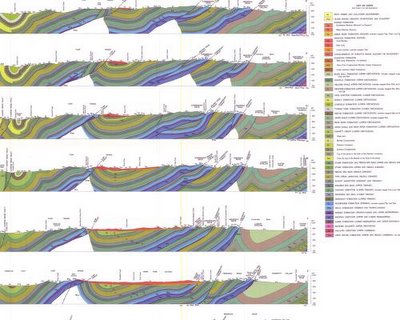

The larger, urban-geographic effects of war are well-described in this article by Katja Simons: “In the years of war, Beirut was divided along ideological and religious lines. A new mental map of the city emerged. The city was renamed East and West Beirut and was divided by the Green Line of demarcation… Self-sufficient sub-centers developed in different parts of the city, preventing civic interaction throughout Beirut. People fled the city and moved to safer places at the periphery. Shop owners and businesses followed, moving to the coastal areas north of the city where new suburban commercial centers mushroomed.”

A new geography of investment soon followed; and, beyond the bombs, Beirut’s infrastructure was transformed.

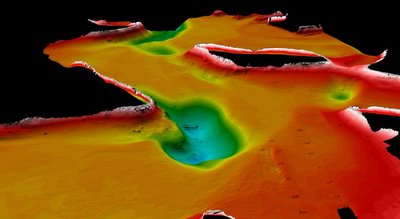

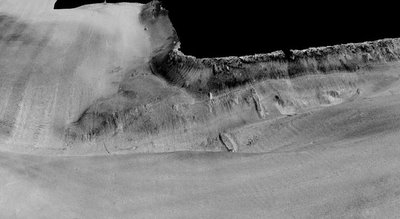

These internal erasures also affected the city’s natural coastline. The port of Beirut, for instance, served as a dumping ground for rubbish, as disposal of waste by other means was too dangerous. A moving coastline of garbage slowly infilled the sea.

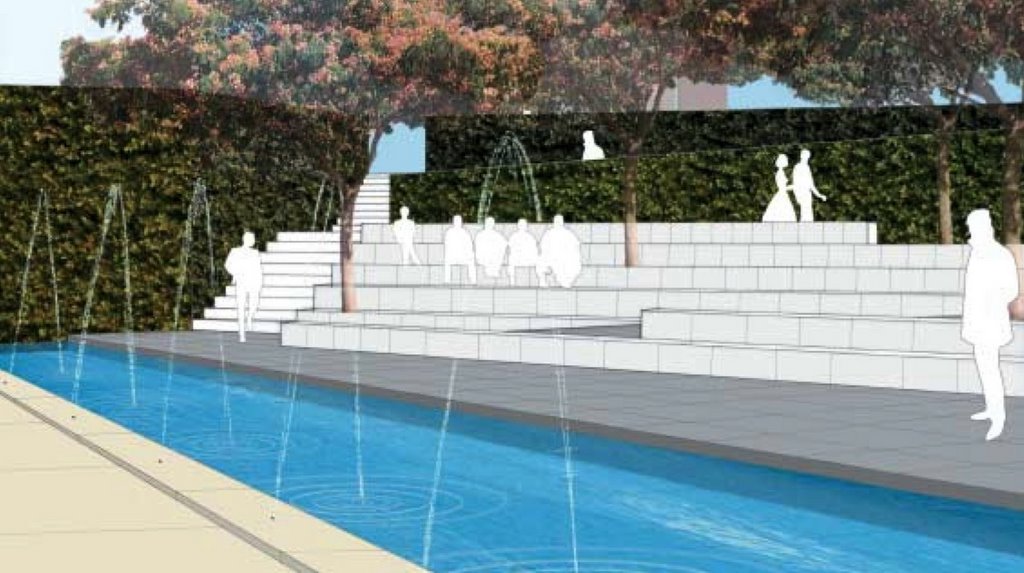

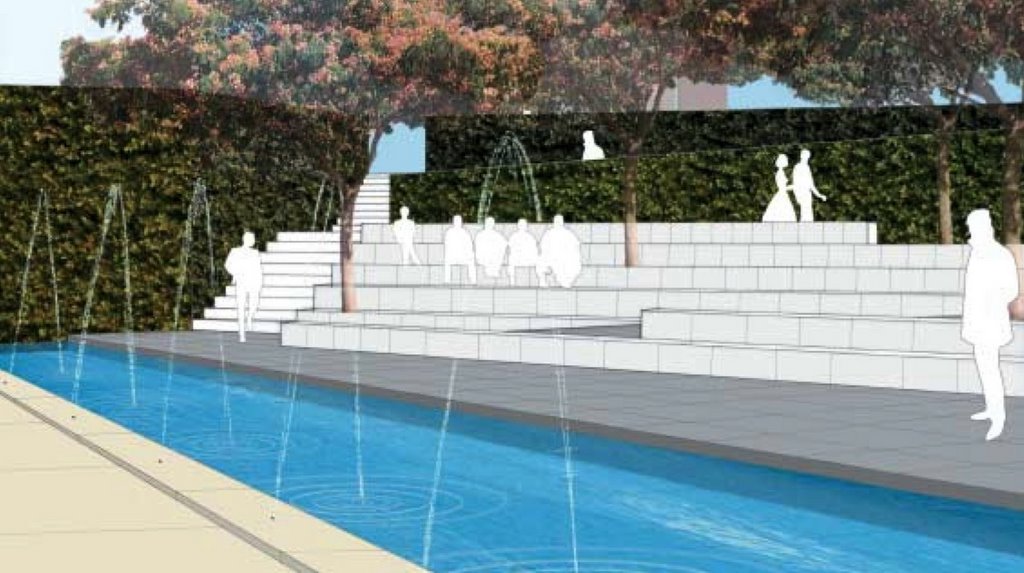

[Image: By Gustafson Porter].

[Image: By Gustafson Porter].

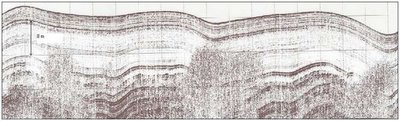

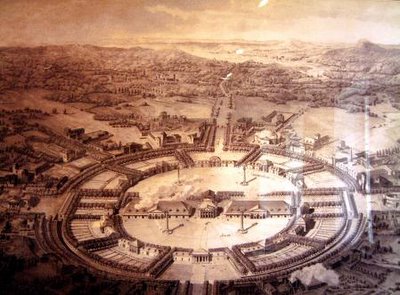

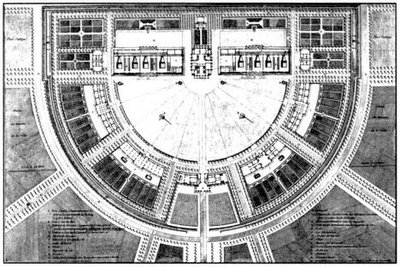

“The shoreline of Beirut has continuously evolved throughout history,” a landscape proposal by Gustafson Porter explains. In that proposal, Beirut’s “lost city coastline has become the inspiration for the creation of a series of new urban spaces.”

[Images: By Gustafson Porter].

[Images: By Gustafson Porter].

“Within the historic context of the evolving shoreline, Gustafson Porter has suggested a new line… revealing elements of the changing historical coastline and acting as a connective spine. On the ground it is marked by a continuous line of white limestone that is accompanied by a wide pedestrian promenade lined by an avenue of distinctive palms (Roystonia regia).” (Download their PDF for more).

[Image: By Gustafson Porter].

[Image: By Gustafson Porter].

What’s interesting here is the idea of building a new coastline, internal to the city. Framing that as a walk, an urban unit, and then leading people along this imagined shore. A new outside, inside.

All the old Devonian coastlines of Manhattan recreated for a day by a series of guided walks. You can download an MP3; it tells you how deep the water was at the corner of Front and John. Where reefs once grew. Marking those with white limestone: here was the sea…

BLDGBLOG Presents: The Paleo-Coastal Walkway, a new guide to the lost seas of Manhattan.

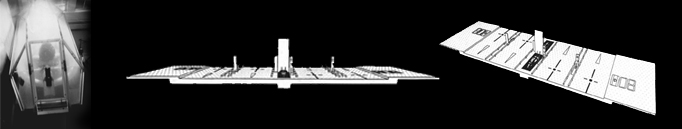

[Image: Bernard Khoury, Checkpoints, 1994].

[Image: Bernard Khoury, Checkpoints, 1994].

In any case, Lebanese architect Bernard Khoury seems to view war as architecture pursued by other means. (Or perhaps vice versa).

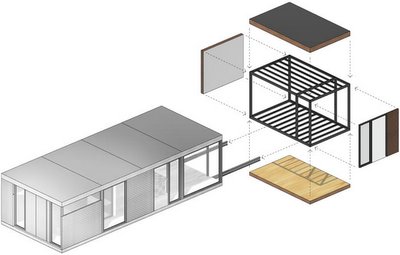

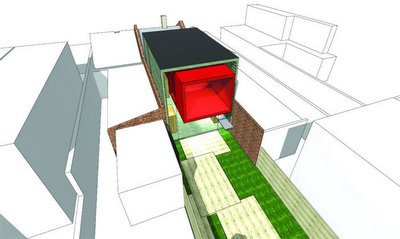

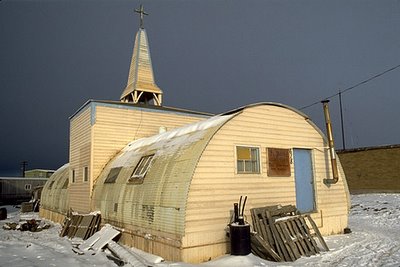

Khoury, for instance, directly confronts the architecture of military control in a series of sci-fi urban checkpoints: “Our proposal plans for high-tech retractable and inhabitable structures that include monitoring systems. While at rest, the checkpoints are dissimulated below the tarmac, they are brought back above the surface when their operators are on duty. The checkpoints establish new roadmaps, they create another battlefield through which the whole territory is linked. The public transits through the selected points in the city, moves into the matrix to be referenced, crosschecked.”

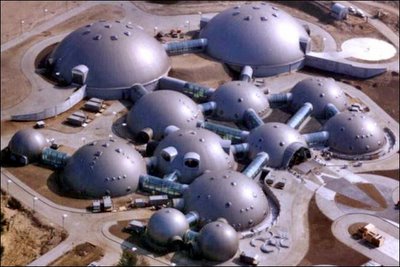

[Image: Bernard Khoury, B018, 1998].

[Image: Bernard Khoury, B018, 1998].

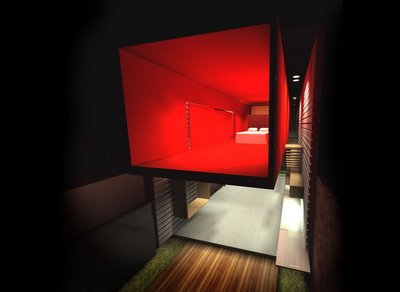

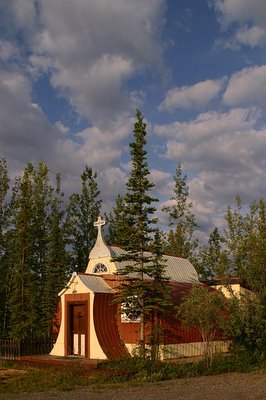

Khoury’s most famous work, however, is the Beiruti nightclub, B018, which melds an urban, post-war bunker aesthetic with the world of hydraulic disco: “The project is built below ground. Its façade is pressed into the ground to avoid the over exposure of a mass that could act as a rhetorical monument. The building is embedded in a circular concrete disc slightly above tarmac level. At rest, it is almost invisible. It comes to life in the late hours of the night when its articulated roof structure constructed in heavy metal retracts hydraulically. The opening of the roof exposes the club to the world above and reveals the cityscape as an urban backdrop to the patrons below.”

Checkpoints, bunkers, new walkways, moving coastlines, oblique forms of entry – architectural responses to urban warfare could take up a whole website of their own. It’s a theme I’ll return to.

For a bit more reading, meanwhile, check out this paper on war and anxiety, from the excellent Cabinet Magazine.

[Image: From Wonder Beirut, 1997-2004, by Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige].

[Image: From Wonder Beirut, 1997-2004, by Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige].

[Image: By

[Image: By

[Images: By

[Images: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: Bernard Khoury,

[Image: Bernard Khoury,  [Image: Bernard Khoury,

[Image: Bernard Khoury,