With drought on my mind, it was interesting to come across two new articles in The New York Times today, both about the United States of waterlessness.

The less interesting of the two tells us that “[w]ater levels in the Great Lakes are falling; Lake Ontario, for example, is about seven inches below where it was a year ago” – and, “for every inch of water that the lakes lose, the ships that ferry bulk materials across them must lighten their loads… or risk running aground.”

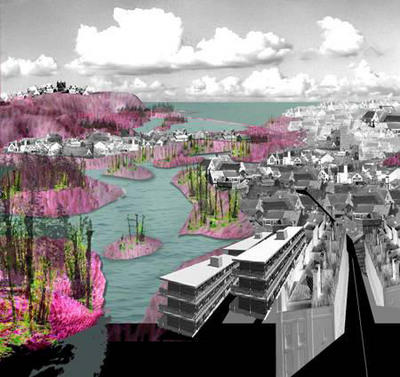

[Image: The Great Lakes are draining; photo by James Rajotte for The New York Times].

[Image: The Great Lakes are draining; photo by James Rajotte for The New York Times].

What’s causing this? “Most environmental researchers,” we read, “say that low precipitation, mild winters and high evaporation, due largely to a lack of heavy ice covers to shield cold lake waters from the warmer air above, are depleting the lakes.”

I’m reminded of something Alex Trevi sent me several weeks ago, in which writer and comedian Garrison Keillor speculates as to what might happen if the state of Minnesota sold all the water in Lake Superior.

Keillor describes a fantastical project called Excelsior, in which the Governor of Minnesota “will stand on a platform in Duluth and pull a golden lanyard, opening the gates of the Superior Diversion Canal, a concrete waterway the size of the Suez. Water from Lake Superior will flood into the canal at a rate of 50 billion gal. per hour and go south.”

It will flow into the St. Croix River, to the Mississippi, south to an aqueduct at Keokuk, Iowa, and from there west to the Colorado River and into the Grand Canyon and many other southwestern canyons, filling them up to the rims – enough water to supply the parched Southwest from Los Angeles to Santa Fe for more than 50 years.

The drained landscape left behind will be renamed the Superior Canyon – and the Superior Canyon, Keillor says, will put the Grand Canyon to shame. “It’s bigger, for one thing,” he writes, “plus it has islands and sites of famous shipwrecks. You’ll have a monorail tour of the sites with crumpled hulls of ships. Very respectful.”

By 2006, Keillor speculated (he was writing from the Hootie & the Blowfish-filled year of 1995):

Lake Superior will be gone, and its islands will be wooded buttes rising above the fertile coulees of the basin. A river will run through it, the Riviera River, and great glittering casinos like the Corn Palace, the Voyageur, the Big Kawishiwi, the Tamarack Sands, the Clair de Loon, the Sileaux, the Garage Mahal, the Glacial Sands, the Temple of Denture, the Golden Mukooda will lie across the basin like diamonds in a dish. Family-style casinos, with theme parks and sensational water rides on the rivers cascading over the north rim, plus high-rise hotels and time-share condominiums. Currently there are no building restrictions in Lake Superior; developers will be free to create high-rises in the shape of grain elevators, casinos shaped like casserole dishes, accordions, automatic washers. Celebrities will flock to the canyon. You’ll see guys on the Letterman show who, when Dave asks, “Where you going next month, pal?” will say, “I’ll be in Minnesota, Dave, playing four weeks at the Pokegama.” Tourism will jump 1,000%. Guys on the red-eye from L.A. to New York will look out and see a blaze of light off the left wing and ask the flight attendant, “What’s that?” And she’ll say, “Minnesota, of course.”

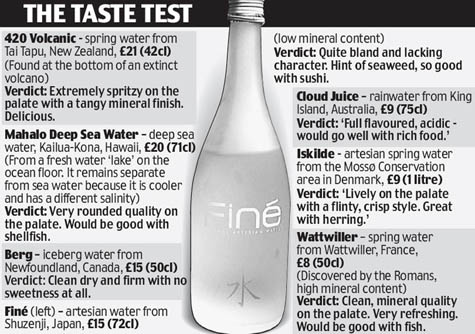

All of which actually reminds of Lebbeus Woods, and his vision of a drained Manhattan.

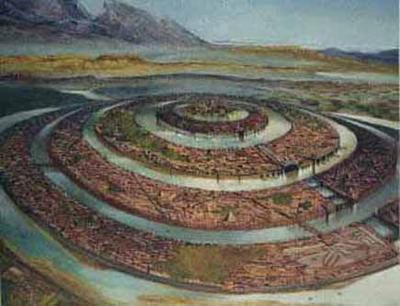

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan; view larger].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan; view larger].

But perhaps such a willfully fictive reference overlooks the reality of the drought(s) now creeping up on the United States.

In a massive new article published this weekend in The New York Times, we’re given a long and rather alarming look at the lack of water in the American west, focusing on the decline of the Colorado River.

A catastrophic reduction in the flow of the Colorado River – which mostly consists of snowmelt from the Rocky Mountains – has always served as a kind of thought experiment for water engineers, a risk situation from the outer edge of their practical imaginations. Some 30 million people depend on that water. A greatly reduced river would wreak chaos in seven states: Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada and California. An almost unfathomable legal morass might well result, with farmers suing the federal government; cities suing cities; states suing states; Indian nations suing state officials; and foreign nations (by treaty, Mexico has a small claim on the river) bringing international law to bear on the United States government.

And it will happen; this “unfathomable” situation will someday occur. The American West will run out of water.

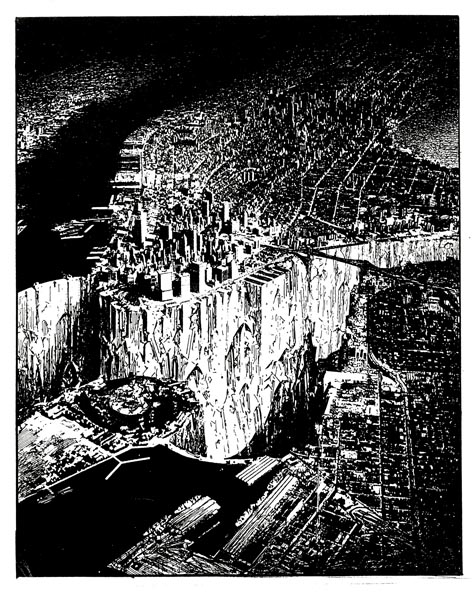

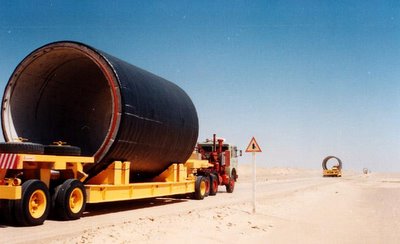

[Image: Simon Norfolk, a photographer previously interviewed by BLDGBLOG, taken for The New York Times].

[Image: Simon Norfolk, a photographer previously interviewed by BLDGBLOG, taken for The New York Times].

Or will it?

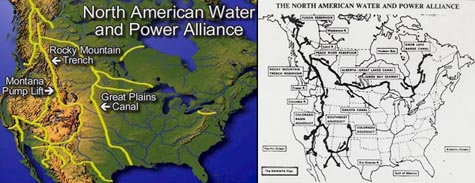

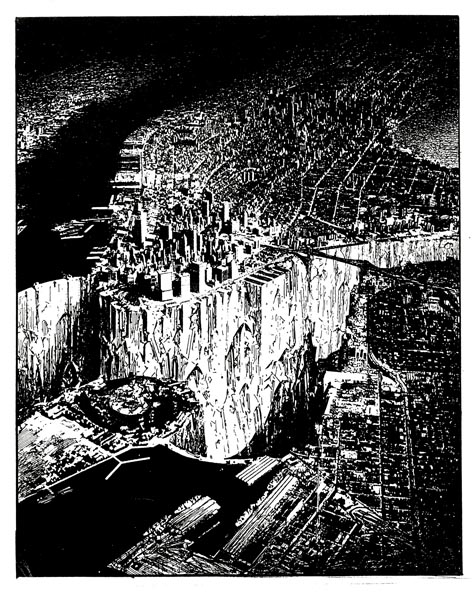

At one point in his genuinely brilliant book Cadillac Desert, Marc Reisner describes something called N.A.W.A.P.A.: the North American Water and Power Alliance. N.A.W.A.P.A. is nothing less than the gonzo hydrological fantasy project of a particular group of U.S. water engineers. N.A.W.A.P.A., Reisner tells us, would “solve at one stroke all the West’s problems with water” – but it would also take “a $6-trillion economy” to pay for it, and “it might require taking Canada by force.”

He quips that British Columbia “is to water what Russia is to land,” and so N.A.W.A.P.A., if realized, would tap those unexploited natural waterways and bring them down south to fill the cups of Uncle Sam. Canadians, we read, “have viewed all of this with a mixture of horror, amusement, and avarice” – but what exactly is “all of this”?

Reisner:

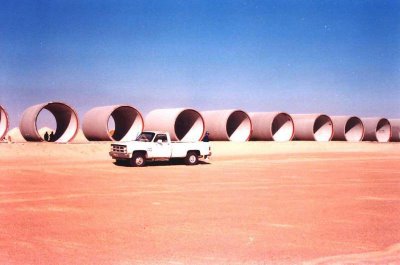

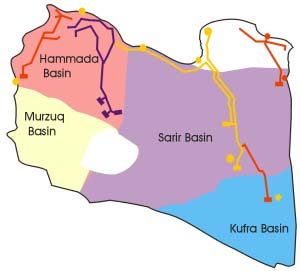

Visualize, then, a series of towering dams in the deep river canyons of British Columbia – dams that are 800, 1,500, even 1,700 feet high. Visualize reservoirs backing up behind them for hundreds of miles – reservoirs among which Lake Mead would be merely regulation-size. Visualize the flow of the Susitna River, the Copper, the Tanana, and the upper Yukon running in reverse, pushed through the Saint Elias Mountains by million-horsepower pumps, then dumped into nature’s second-largest natural reservoir, the Rocky Mountain Trench. Humbled only by the Great Rift Valley of Africa, the trench would serve as the continent’s hydrologic switching yard, storing 400 million acre-feet of water in a reservoir 500 miles long.

And that’s barely half the project!

The project would ultimately make “the Mojave Desert green,” we read, diverting Canada’s fresh water south to the faucets of greater Los Angeles – thus destroying almost every salmon fishery between Anchorage and Vancouver, and even “rais[ing] the level of all five [Great Lakes],” in the process.

After all, N.A.W.A.P.A. also means that the Great Lakes would be connected to the center of the North American continent by something called the Canadian–Great Lakes Waterway.

But N.A.W.A.P.A. is an old plan; it’s been gathering dust since the 1980s. No one now is seriously considering building it. It’s literally history.

But who knows – perhaps 2008 is the year N.A.W.A.P.A. makes a comeback. Or, perhaps, in January 2010, after another dry winter, Los Angeles voters will start to get thirsty. Perhaps some well-positioned Senators, in 2011, might even start making phonecalls north. Perhaps, in 2012, some recent graduates from water management programs at state-funded universities in Illinois or Utah might catch the itch of moral rebellion; they might then start redrawing their personal maps of the continent, going to bed at night with visions of massive dams in their heads, writing position papers for peer-reviewed hydrological engineering magazines.

But who knows – perhaps 2008 is the year N.A.W.A.P.A. makes a comeback. Or, perhaps, in January 2010, after another dry winter, Los Angeles voters will start to get thirsty. Perhaps some well-positioned Senators, in 2011, might even start making phonecalls north. Perhaps, in 2012, some recent graduates from water management programs at state-funded universities in Illinois or Utah might catch the itch of moral rebellion; they might then start redrawing their personal maps of the continent, going to bed at night with visions of massive dams in their heads, writing position papers for peer-reviewed hydrological engineering magazines.

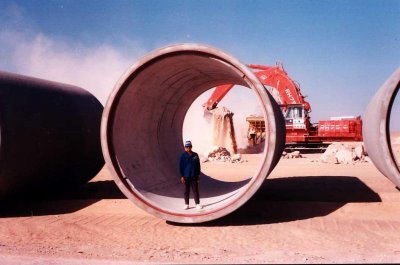

Perhaps, in 2017, ten years from now, BLDGBLOG – if it’s still around – will even be reporting from the rims of these gigantic structures, thrown up overnight in the remote and untrafficked darkness of riverine western Canada. Long, perfectly calibrated concrete sluices and pumps will bring water thousands of miles south through redwood forests to the open basins of California’s reservoirs, and photographs of their incomprehensibly expensive and exactly poured geometry will elicit whistles of embarrassed awe from readers on the streets of Weehawken.

[Image: A fish-cleaning station in Las Vegas Bay, now abandoned by the West’s sinking waters; taken by Simon Norfolk for The New York Times].

[Image: A fish-cleaning station in Las Vegas Bay, now abandoned by the West’s sinking waters; taken by Simon Norfolk for The New York Times].

Or perhaps it won’t be N.A.W.A.P.A. after all, but some titanic new project identical in all but name.

Will California wait for the coming drought to destroy it – or will the state take drastic measures?

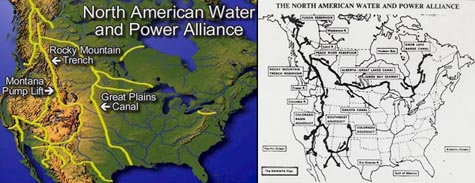

The city of Venice has begun to rebrand its tap water, calling it Acqua Veritas, in an attempt to woo both residents and tourists away from the environmental hazards (and waste collection nightmare) of bottled water.

The city of Venice has begun to rebrand its tap water, calling it Acqua Veritas, in an attempt to woo both residents and tourists away from the environmental hazards (and waste collection nightmare) of bottled water.  [Image: Marcel Duchamp, 50 cc of Paris Air (1919), courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art].

[Image: Marcel Duchamp, 50 cc of Paris Air (1919), courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art]. [Image: The water selection at

[Image: The water selection at  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The Great Lakes are draining; photo by James Rajotte for

[Image: The Great Lakes are draining; photo by James Rajotte for  [Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan; view

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan; view  [Image: Simon Norfolk, a photographer previously

[Image: Simon Norfolk, a photographer previously  But who knows – perhaps 2008 is the year N.A.W.A.P.A. makes a comeback. Or, perhaps, in January 2010, after another dry winter, Los Angeles voters will start to get thirsty. Perhaps some well-positioned Senators, in 2011, might even start making phonecalls north. Perhaps, in 2012, some recent graduates from water management programs at state-funded universities in Illinois or Utah might catch the itch of moral rebellion; they might then start redrawing their personal maps of the continent, going to bed at night with visions of massive dams in their heads, writing position papers for peer-reviewed hydrological engineering magazines.

But who knows – perhaps 2008 is the year N.A.W.A.P.A. makes a comeback. Or, perhaps, in January 2010, after another dry winter, Los Angeles voters will start to get thirsty. Perhaps some well-positioned Senators, in 2011, might even start making phonecalls north. Perhaps, in 2012, some recent graduates from water management programs at state-funded universities in Illinois or Utah might catch the itch of moral rebellion; they might then start redrawing their personal maps of the continent, going to bed at night with visions of massive dams in their heads, writing position papers for peer-reviewed hydrological engineering magazines.  [Image: A fish-cleaning station in Las Vegas Bay, now abandoned by the West’s sinking waters; taken by

[Image: A fish-cleaning station in Las Vegas Bay, now abandoned by the West’s sinking waters; taken by

[Image: By Ozier Muhammad for

[Image: By Ozier Muhammad for

[Images: By Ozier Muhammad for

[Images: By Ozier Muhammad for  [Image: By Ozier Muhammad for

[Image: By Ozier Muhammad for

[Image: Photograph by Robert Polidori, from “City of Water” by David Grann, The New Yorker, September 1, 2003].

[Image: Photograph by Robert Polidori, from “City of Water” by David Grann, The New Yorker, September 1, 2003].

[Image: Replacing the rivers and militarizing the water supply: “Soldiers in Harbin, in northeast China, checked water supplies on Tuesday.” Imaginechina/

[Image: Replacing the rivers and militarizing the water supply: “Soldiers in Harbin, in northeast China, checked water supplies on Tuesday.” Imaginechina/