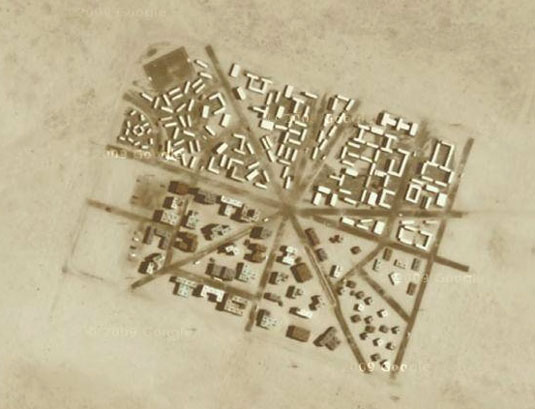

[Image: Yodaville, via Google Maps].

[Image: Yodaville, via Google Maps].

Yodaville is a fake city in the Arizona desert used for bombing runs by the U.S. Air Force. Writing for Air & Space Magazine back in 2009, Ed Darack wrote that, while tagging along on a training mission, he noticed “a small town in the distance—which, as we got closer, proved to have some pretty big buildings, some of them four stories high.”

As towns go, this one is relatively new, having sprung up in 1999. But nobody lives there. And the buildings are all made of stacked shipping containers. Formally known as Urban Target Complex (R-2301-West), the Marines know it as “Yodaville” (named after the call sign of Major Floyd Usry, who first envisioned the complex).

As one instructor tells Darack, “The urban layout is actually very similar to the terrain in many villages in Iraq and Afghanistan.”

The Urban Target Complex, or UTC, was soon “lit up with red tracer rounds and bright yellow and white rocket streaks,” till it “looked like it was barely able to keep standing”:

The artillery and mortars started firing, troops advanced toward the target complex, and aircraft of all types—carefully controlled by students on the mountain top—mounted one attack run after another. At one point so much smoke and dust filled the air above the “enemy” that nothing could be seen of the target—just one of the real-world problems the students had to learn to cope with that day.

In a recent article for the Tate, writer Matthew Flintham explores “the idea of landscape as an extension of the military imagination.” Referring specifically to the UK, he adds that what he perceives as a contemporary “lack of artistic engagement with the activities of the Ministry of Defence (MoD) is perhaps principally due to the relative segregation of defence personnel, land and airspace from the civil domain.”

Flintham points out—again, referring to the UK—that “today’s MoD has its own vast training estate with numerous barracks and an enormous stock of housing, all of which are detached from public scrutiny. The public are prevented from accessing many areas of the defence estate for two reasons: the extreme danger of live weapons and hazardous activities (and related issues of potential litigation), and the restrictions on privileged, strategic or commercial information in the interests of national security.” This has the effect that these sorts of military landscapes not only fall outside critical scrutiny—and also remain, with very few exceptions, all but invisible to architectural critique—but that their only real role in the public imagination is entirely speculative, often based solely on rumor and verging on conspiracy.

While Flintham thus calls for a more active artistic engagement with military landscapes, exploring what he calls the “military-pastoral complex,” I would echo that with a related suggestion that spaces such as Yodaville belong on the architectural itinerary of today’s design writers, critics, and students.

Given the mitigation of the very obvious problems Flintham himself points out—such as site contamination, unexploded ordnance, and national security leaks—it would be thrilling to see a new kind of “fortifications tour,” one that might bring these sorts of facilities into the public experience.

[Image: Photo by Richard Misrach, courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art, from Bravo 20].

[Image: Photo by Richard Misrach, courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art, from Bravo 20].

An interesting possibility for this sort of national refocusing on military landscapes comes from artists Richard and Myriam Misrach. The Misrachs have proposed a “Bravo 20 National Park“—that is, “turning the blasted range into a National Park of bombing,” as the Center for Land Use Interpretation phrases it. “When the Navy’s use of Bravo 20 was up for Congressional review in 1999,” CLUI continues, “Misrach made one more heroic, quixotic, and failed attempt to get his proposal seriously considered. Instead, the Navy has increased its use of Bravo 20, and the four other ranges around Fallon, and has been authorized to expand their terrestrial holdings in the area by over 100,000 acres.”

So what, for instance, might something like a Yodaville National Park, or Urban Target Complex National Monument, look like? How would it be managed, touristed, explored, mapped, and understood? What sorts of trails and interpretive centers might it host? Alternatively, in much the same way that the Unabomber’s cabin is currently on display at the Newseum in Washington D.C., could Yodaville somehow, someday, become part of a distributed collection of sites owned and operated by the Smithsonian, the National Building Museum, or, for that matter, UNESCO, in the latter case with Arizona’s simulated battlegrounds joining Greek temples as world heritage sites?

In any case, bringing spaces of military simulation into the architectural discussion, and reading about Yodaville in, say, Architectural Record instead of—or in addition to—Air & Space Magazine, would help to demystify the many, otherwise off-limits, landscapes produced (and, of course, destroyed) by military activity. Better, this would reveal even the cloudiest of federal lands as spatial projects, nationally important places that—again, given declassification and appropriate environmental remediation—might hold unexpected insights for design practitioners, let alone for critics, the public, and national historians.

(Thanks to Mark Simpkins for the Tate link).

[Image: The Georgian cave monastery of Vardzia, via

[Image: The Georgian cave monastery of Vardzia, via  [Image: Vardzia, via

[Image: Vardzia, via  [Images: Vardzia, via

[Images: Vardzia, via  [Images: Vardzia, via

[Images: Vardzia, via

[Images: Vardzia, as seen in some

[Images: Vardzia, as seen in some  [Images: Vardzia, via

[Images: Vardzia, via