[Image: “Shopping mall parking lot, Dubai,” (2009) by Bas Princen].

[Image: “Shopping mall parking lot, Dubai,” (2009) by Bas Princen].

Photographer Bas Princen has a fantastic new exhibition, called “Refuge,” up at Storefront for Art and Architecture. Tonight, Tuesday, May 11, Princen will be at the gallery for a public event and opening, and it’s well worth checking out.

Storefront describes the show as a “photographic fiction”:

Although it is the result of extensive travels and research in five cities of the Middle East and Turkey—Istanbul, Beirut, Amman, Cairo and Dubai—it could just as easily pass as the pictorial record of a dérive through a single, imaginary city: a city without a center, populated by extraordinary and at times implausible architectural artefacts; an urban laboratory whose physical traits are defined by migratory flows, spatial transformation and geopolitical flux on a continental scale.

[Image: “Cooling plant, Dubai,” (2009) by Bas Princen].

[Image: “Cooling plant, Dubai,” (2009) by Bas Princen].

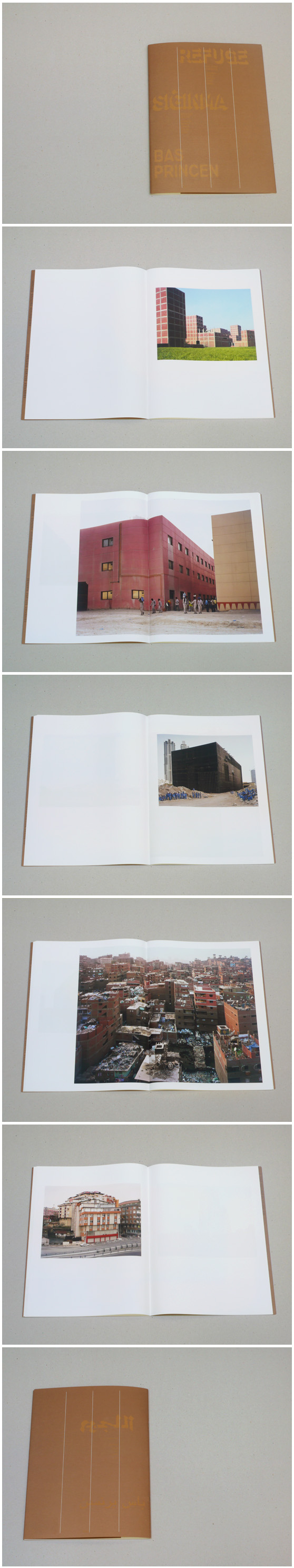

As part of a poster published in tandem with the exhibition, former Storefront director Joseph Grima interviewed Princen about his work, starting off with an inquiry into how Princen’s own background in architectural studies might have affected his photographic approach to the built and natural environments (the interview is also available at Domus).

[Image: “Sand ridge, Amman,” (2009) by Bas Princen].

[Image: “Sand ridge, Amman,” (2009) by Bas Princen].

Princen remarks that, for him, “the camera [is] a tool to construct ideas on space or places, or ideas on architecture and landscape.” For “Refuge,” in particular, he explains that:

My main objective with this project was to create a series of photographs in which Amman, Beirut, Cairo, Dubai and Istanbul disappear as individual cities and as specific places, dissolving instead into a new kind of city, an imaginary urban entity in formation. This premise directed me to specific places in the periphery where pieces of the city are forming, almost like islands, and this accounts for my interest in the refugee camps and gated communities.

Zeroing in specifically on the architecture, Grima then asks him about “the ubiquity of the modernist reinforced-concrete slab-and-column structure,” a construction technique clearly visible in the photographs reproduced here.

[Images: “Former sugarcane field, Cairo,” (2009) and “Ringroad, Cairo,” (2009) by Bas Princen].

[Images: “Former sugarcane field, Cairo,” (2009) and “Ringroad, Cairo,” (2009) by Bas Princen].

Grima suggests that, as a tactic for assembling buildings, this construction technique is “strongly reminiscent of Le Corbusier’s Maison Domino.” Princen’s response is brilliant, and worth quoting at length:

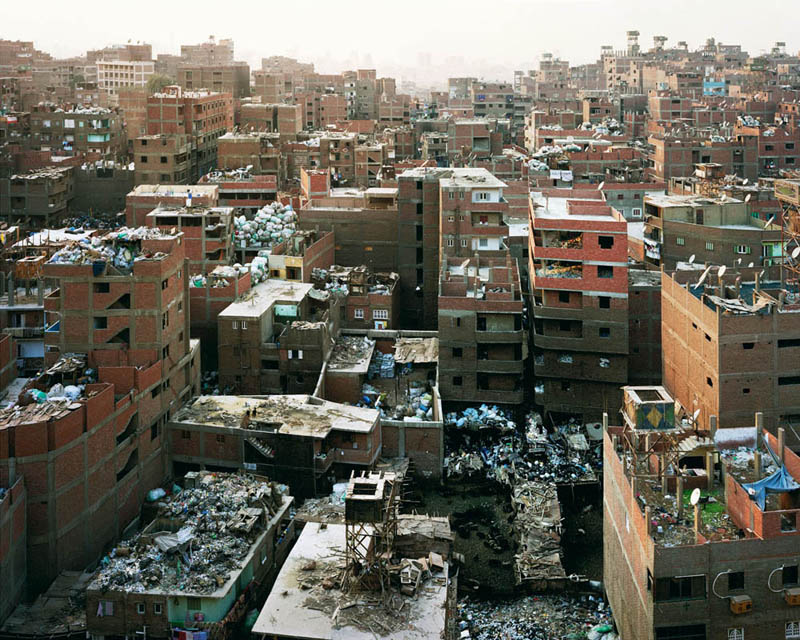

It is fascinating that Maison Domino, the quintessential modernist prototype conceived as a universal answer to the housing problem, has in the end inspired the method of choice for informal construction, with or without the help of architects. The many interpretations of the famous Maison Domino prototype I’ve seen are a clear indication that is has become the most universally successful type of construction, but nothing prepared me for Cairo, where this structural system is really pushed to the limits—not only because these buildings in red-brick-and-concrete grids rise to 16 or 17 floors, but also because three quarters of the city is constructed in this way. It is a mesmerizing fictional experience: driving on an elevated highway through this city of red brick towers, trying to imagine who is actually living there.

This latter remark—Princen’s difficulty in imagining these sorts of landscape humanly inhabited—sets the stage for a remark, later in the interview, when Princen mentions that he attempts to maintain a human presence in his photographs—in other words, they are not anthropologically empty landscapes.

[Images: “Mokkatam Ridge (garbage recycling city), Cairo,” (2009) by Bas Princen].

[Images: “Mokkatam Ridge (garbage recycling city), Cairo,” (2009) by Bas Princen].

He adds that “the so-called ‘middle distance'”—the scale inhabited by humans—”has not been used much in recent architectural photography,” an industry that tends now to focus on one of two extremes: “the architectural object on the one hand and the cityscape on the other.” But “it is exactly in this middle distance,” Princen counters, “that the human figure becomes an interesting element: it cannot be shown as the main subject, but will always be defined by the relationship with its surroundings, to put an extra meaning or layer on the landscape or object that is photographed.”

As a result, Princen’s photos show us diminutive humans, stranded amidst incomprehensible architectural forms and massive landscapes, neither urban nor rural, pursuing admirably self-directed goals through which to give themselves meaning or, depending on how you look at it, utterly vacuous tasks that they refuse to admit should be abandoned.

[Images: Spreads from “Refuge” by Bas Princen].

[Images: Spreads from “Refuge” by Bas Princen].

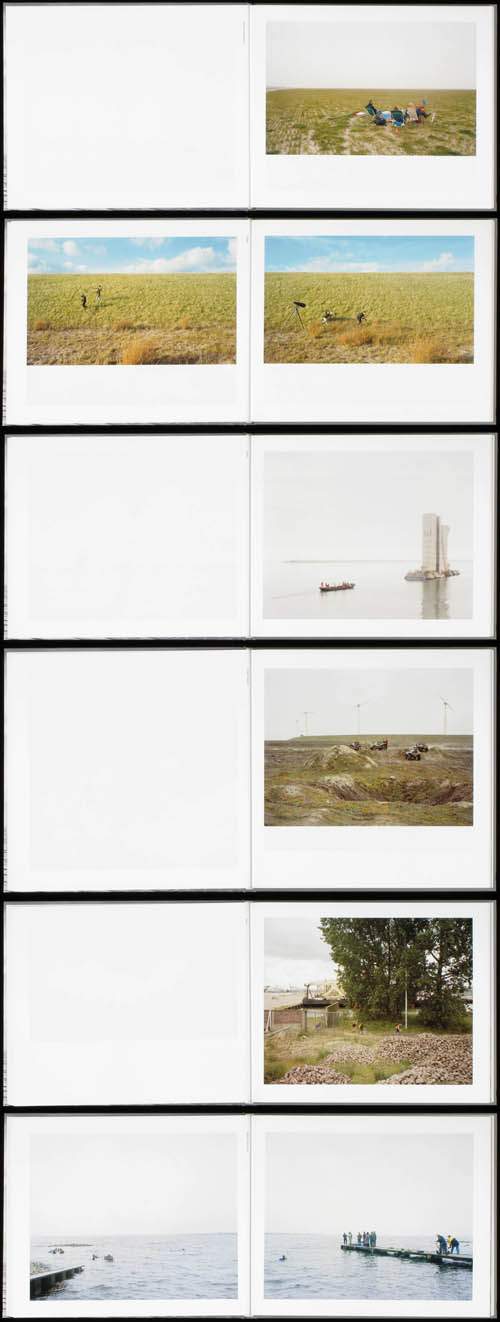

Princen has rapidly become one of my favorite photographers; his earlier work, for instance, collected in the stunning Artificial Arcadia, shows, in Grima’s words, “the contemporary landscape as something invariably artificial, even when there is no sign of human intervention.”

What this means, more concretely, is that the book documents transitional landscapes scattered here and there around the Netherlands: “future suburbs,” highway overpass construction sites deep in forested housing estates, thickets planted for no ecological reason other than to block the sounds of a nearby airfield—landscapes that are at once highly abstract, yet ingeniously colonized by the local residents who have turned them into 4×4 race tracks, kite-flying grounds, fishing ponds, sites for paintball tournaments, and more.

They are also landscapes that have been generated, as if unconsciously, by industrial processes seated and operating elsewhere; as such, Princen shows us clay and sand depots, harbor excavation sites, and dumping grounds for contaminated silt and soil. But then, there, on top of those strange landforms, built on no recognizable human scale, there are weekend nature enthusiasts with their cameras out, stalking rare insects and birds that have settled these disrupted terrains.

The book, frankly, is pretty incredible. Take the “acoustic forest”: as mentioned above, it is a landscape “maintained to cushion the noise of a military base and airfield,” showing us an artificial ecosystem as military-sonic camouflage, like something out of Nick Sowers‘s research.

It’s the small humanist flips, however, that interest me so much; a sand dyke, for example, built ostensibly for the same purpose as above, “to shield a new housing estate from the noise of a military airfield,” but that has since been transformed into a communal meeting place where “residents gather on the sand dyke to watch the planes.”

[Images: Spreads from Artificial Arcadia by Bas Princen].

[Images: Spreads from Artificial Arcadia by Bas Princen].

These makeshift, highly unexpected communities—such as model-airplane enthusiasts hanging out together in remote hardware store parking lots—are rampant throughout Artificial Arcadia and, indeed, Bas Princen’s work altogether. One of the most intriguing examples of this is the site of a new highway being constructed through forested suburbs; far from the paving stage, however, it is simply a muddy scar through the trees, looking more like a landslide, with no actual sense that the construction crews are even coming back to finish it. It is, Princen explains, “a 30-km long highway construction site, cutting through forests and farmlands, skirting villages,” that has since become “a gathering place,” like a piazza or churchyard.

The back of the book states that Princen is interested in documenting “the complex qualities that construct contemporary landscape, such as accessibility, wind direction, water currents and communication networks. In addition the use of certain products, such as kites, mountain bikes and GPS monitors, has a bearing on the way in which landscape is understood.” The landscape is instrumentalized, we might say, distilled through dense layers of technological abstraction to become, once again, a place inhabitable by human activity, however pathetic or impressively persistent it might be.

[Image: “Valley, Beirut,” (2009) by Bas Princen, from “Refuge“].

[Image: “Valley, Beirut,” (2009) by Bas Princen, from “Refuge“].

In any case, the exhibition opening tonight, May 11, at Storefront for Art and Architecture—where Bas Princen will be present in the gallery to kick things off and answer questions—features only his work for “Refuge,” but it promises to be one of the more compelling photography shows in New York this year.

It’s a speculative project, to be sure – but a fun one, and I can’t wait to see what comes up.

It’s a speculative project, to be sure – but a fun one, and I can’t wait to see what comes up.  Continuing:

Continuing: [

[