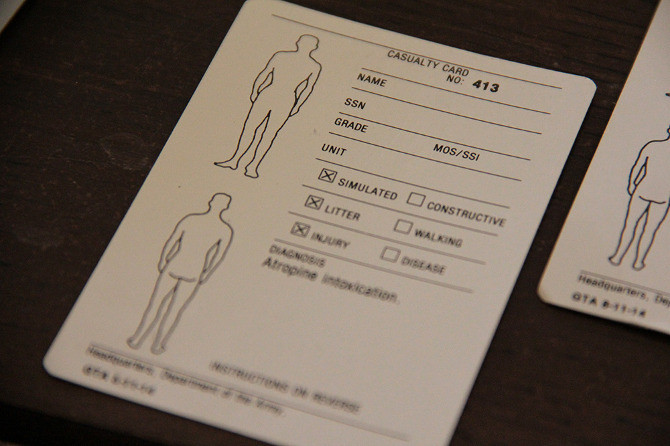

Photo courtesy Scott McGuire.

Photo courtesy Scott McGuire.

(This interview originally published on Venue).

Several years ago, while I was still on the editorial staff at Dwell magazine, I took a daytrip down to the head office of The North Face to visit their equipment design team and learn more about the architecture of tents.

“As a form of minor architecture,” the resulting short article explained, “tents are strangely overlooked. They are portable, temporary, and designed to withstand even the most extreme conditions, but they are usually viewed as simple sporting goods. They are something between a large backpack and outdoor lifestyle gear—certainly not small buildings. But what might an architect learn from the structure and design of a well-made tent?”

Amongst the group of people I spoke with that day was outdoor equipment strategist Scott McGuire, an intense, articulate, and highly focused advocate for all things outdoors. As seen through Scott’s eyes, the flexibility, portability, ease of use, and multi-contextual possibilities of outdoor equipment design began to suggest a more effective realization, I thought, of the avant-garde legacy of 1960s architects like Archigram, who dreamed of impossible instant cities and high-tech nomadic settlements in the middle of nowhere.

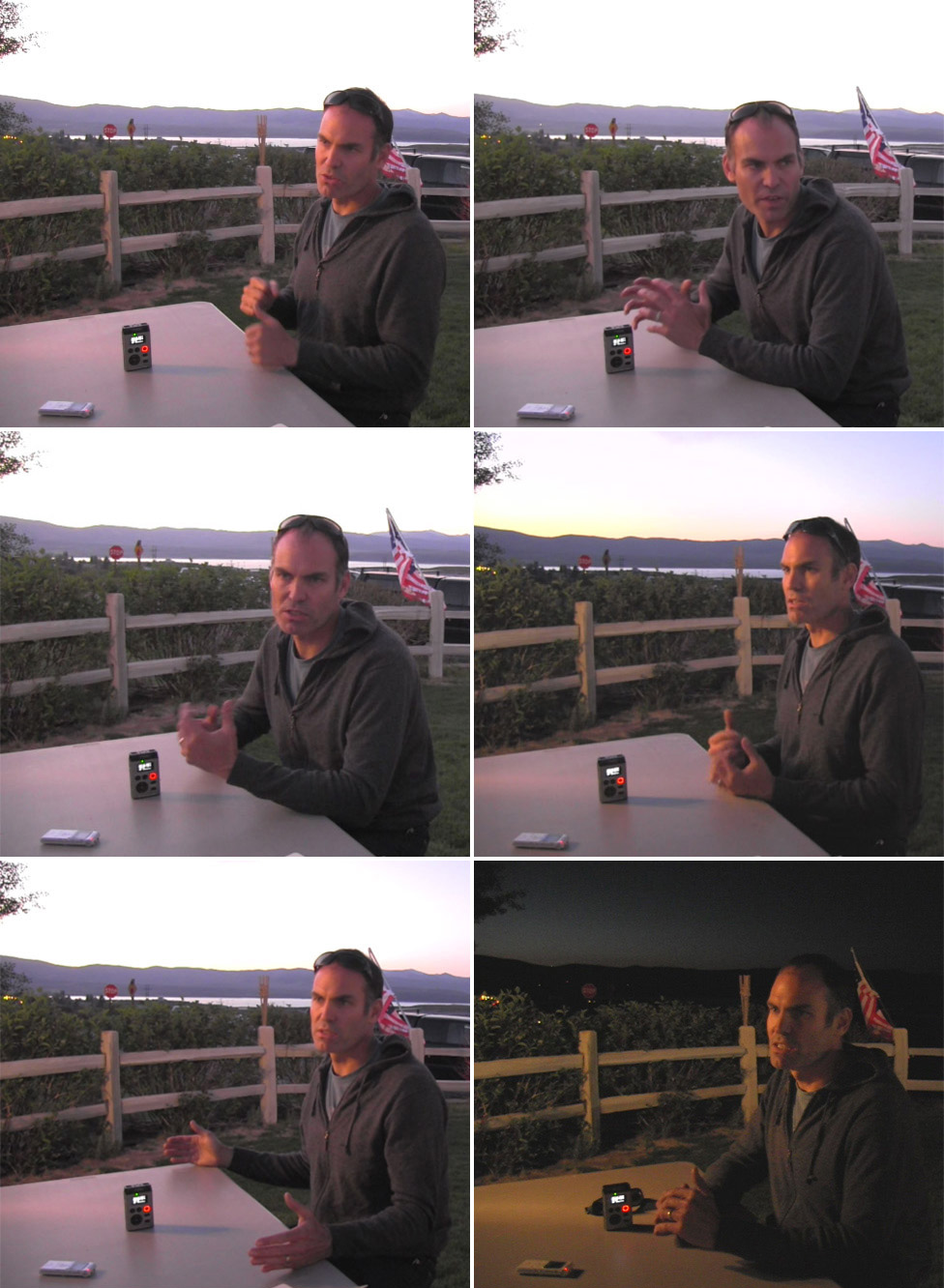

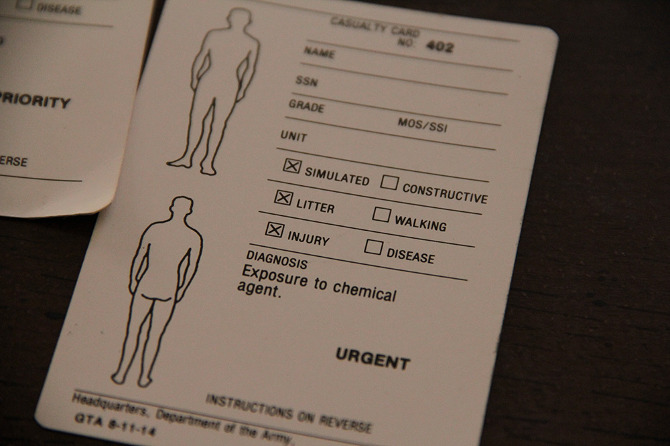

Scott McGuire talks to Venue in Lee Vining, California; Mono Lake can be seen in the background.

Scott McGuire talks to Venue in Lee Vining, California; Mono Lake can be seen in the background.

Intrigued by his perspective on the ways in which outdoor gear can both constrain and expand the ways in which human beings move around in and inhabit wild landscapes, and traveling with Nicola Twilley as part of our collaborative Venue project, I was thrilled to catch up with Scott at a deli in Lee Vining, California, near his home in the Eastern Sierra.

McGuire, who recently left The North Face to set up his own business, called The Mountain Lab, was beyond generous with his time and expertise, happily answering Nicola’s and my questions as the sun set over Mono Lake in the distance. His answers combined a lifelong outdoor enthusiast’s understanding of the natural environment with a granular, almost anthropological analysis of the activities that humans like to perform in those contexts, as well as a designer’s eye for form, function, and material choices.

Indeed, as Scott’s description of the design process makes clear in the following interview, a 40-liter mountaineering pack is revealed literally as a sculpture produced by the interaction between the human body and a particular landscape: the twist to squeeze through a crevasse, or the backward tilt of the head during a belay.

Our conversation ranged from geographic and generational differences in outdoor experiences to the emerging spatial technologies of the U.S. military, and from the rise of BMX and the X Games to the city itself as the new “outdoors,” offering a fascinating perspective on the unexpected ways in which technical equipment can both enable and redefine our relationship with extreme environments.

• • •Geoff Manaugh: I’d like to start by asking you about the constraints you face in the design of outdoor athletic equipment, and how that affects the resulting product. For instance, in designing architecture, you might think about factors such as a building’s visual impact, its environmental performance, or the historic context of where your future structure is meant to be. But if you’re designing something like a tent—a kind of

athletic architecture, if you will—then you’re talking about factors like portability, aerodynamism, cost, weather-proofing, etc.. What design constraints do you face, and how do you prioritize them?

Scott McGuire: The first thing is always the user. Everything has to be very user-centric, in a way that’s perhaps unlike conventional architecture. You might say, “I’m building a house; it’s about this site; it’s about this view; people are going to live in it in a certain way,” but you would rarely design a house based on whether or not someone has a propensity, for example, to use their kitchen utensils with their left hand or their right hand. But when you’re creating a technical product, you become really myopically focused on how that product interacts with an individual. It’s about establishing who that person is.

Of course, if I’m talking about doing a small technical pack that will hold 40 liters for someone who’s going mountaineering—well, I know that same pack may very well be used by someone riding on a bike as a commuter in New York City. Still, when we’re talking about that product, it’s very much about things like: what’s the person who’s going mountaineering wearing? What are they carrying? Where are they going? What environment are they going to be in? How much wear and tear is their pack going to get? As you study the user, you usually end up discovering a lot of nuances about the way they’ll use the product, and they’re often things you wouldn’t normally think about.

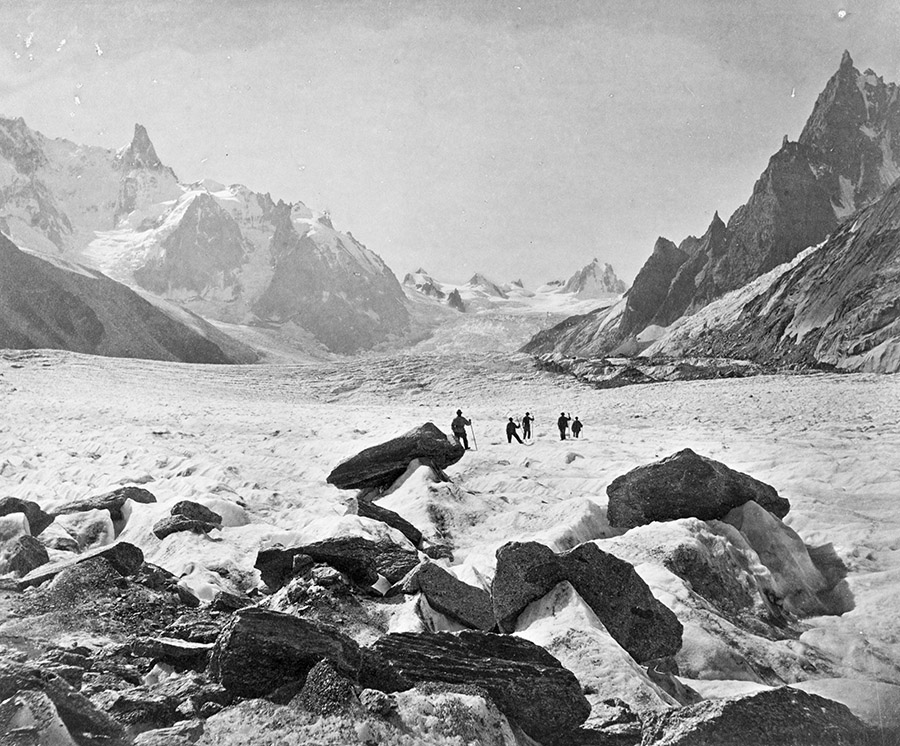

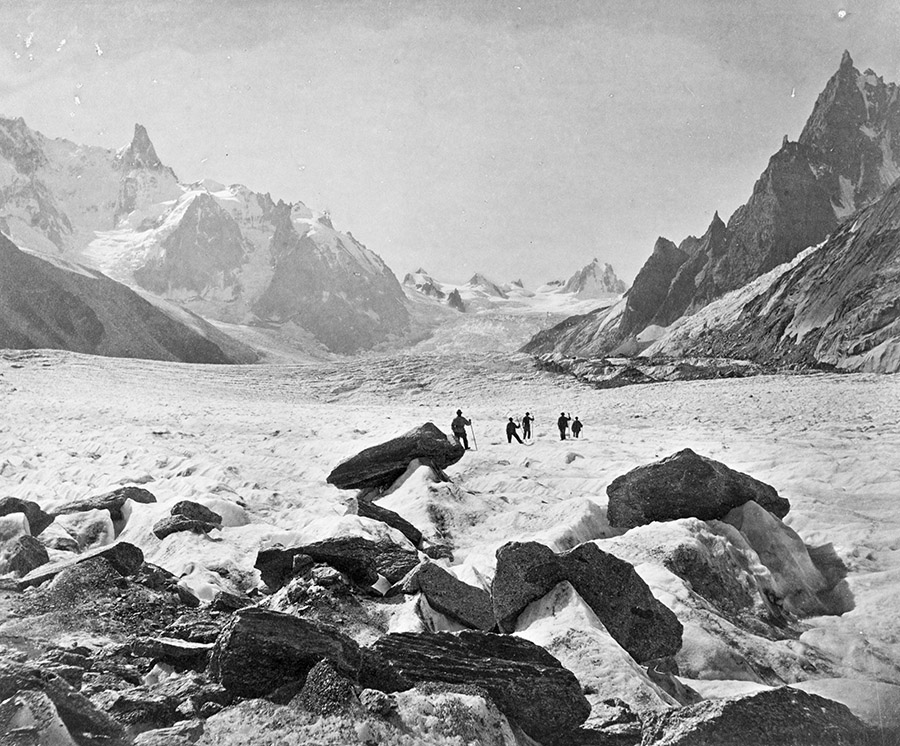

“Mt. Blanc from Le Jardin“; “The Finsteraarhorn“; another view of the Finsteraarhorn; and “Glacier of the Rhone.” All photos taken between 1860 and 1890. Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

“Mt. Blanc from Le Jardin“; “The Finsteraarhorn“; another view of the Finsteraarhorn; and “Glacier of the Rhone.” All photos taken between 1860 and 1890. Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

I’ll give you some examples of how that would work. I’ll stick with the 40-liter technical pack, which is the one you usually find in an area that’s high alpine, above 8000 feet, with year-round glaciers, where there’s lots of climbing and mountaineering. What you’re going to find, obviously, is that people are carrying it. They’re moving at a relatively athletic pace. They want to have the ability to fit the pack.

When we think about fit, it’s not as simple as saying: “This person’s got a 34″ waist, a 19″ back, a 42″ chest, and that’s what we need to focus on.” It’s also the fit based off the way someone moves—what I would call the interaction between the user and the device. The way a 65-liter pack fits someone who’s walking down a manicured trail, doing eight miles a day—the height that their knee climbs and the amount that their body twists—is different than the fit of a 40-liter pack for somebody who’s going up a mountain, where they might be climbing a 45-degree slope. Or they might have somebody on belay and they need to be able to look up, so they need to have a tiny pocket of space so that, with a helmet, they can crane their head back and look up at their partner. The pack can’t get in the way of that.

Three 65-liter packs by The North Face, High Sierra, and Kelty, respectively.

Three 65-liter packs by The North Face, High Sierra, and Kelty, respectively.

Then you add to all that not just an ability to carry weight, but questions like: what does it feel like when an arm comes up to reach for a hold? Or: what happens when you’re trying to twist through a crevasse? There’s a fair amount of time spent really thinking about all of those elements on the body.

And then you run into some really interesting places when you start thinking about how the pack comes off the body. What does everybody do when they come to a stop? They take their packs off, throw them on the ground, and sit on them. So you have to think about how your frame system can carry the load one way, while being carried on someone’s back, but also what happens to that frame system when someone sits on it when it’s on the ground. That really nice zipper pocket on the face, the one that’s so great for getting access at the front of the pack—well, what happens when that thing spends a year lying zipper-down, crammed full of mud, with 150 to 200 pounds of person sitting on top of it? A lot of these observations need to take place in the very beginning, to think through these things.

Mountain climbers, Zermatt, Switzerland (1954); photograph by Toni Frissell, courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division.

Mountain climbers, Zermatt, Switzerland (1954); photograph by Toni Frissell, courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division.

That’s basically the fit component of the interaction to the person. The second element is really going to be: what goes into the product? What is the user carrying, and how do they access it? Those two questions live in a symbiotic relationship with each other. It’s also not just about what goes in the pack, but when it goes in, when it comes out, and how it goes back in again.

Taking a conventional top design, you have an open bucket; you open the lid; and you put stuff inside. There are shapes that inherently lend themselves to technical packs: they’re slightly tapered at the bottom, so they stay within the lumbar area, keeping the weight centered over the sacrum. That makes it a little easier when those narrow slots are on your waist, and the V-shape of the pack mimics the shape of your shoulders and chest. What it also does is it creates a bucket that can feed stuff down into the bottom. You want to keep your heavier stuff near your center of gravity—you want to keep it low and tight—preferably right underneath the shoulder blades.

But you also need to think about what’s going in there, in what order. Things like an extra shell, or your spare jacket, or the rope you may or may not need—those can all go in the bottom. But what are the things that are coming on and off, all the time? On a technical climb, if you’re wearing a puffy jacket, well, every time you’re hot, that jacket’s going to come off—maybe ten or fifteen times a day. So how does that go in and how do you maintain access to it in the easiest possible way? How do you make sure you’ve got easy access to things like a first aid kit, in case you’ve got to get to it quick? Where does your headlamp sit so that, when it’s late and you’re finally getting the headlamp out, and it’s probably already dark, you know, intuitively, that it’s in this pocket right here and you don’t have to fumble around and find the headlamp and risk having everything else dump out?

The view from Scott McGuire’s back porch; photo courtesy Scott McGuire.

The view from Scott McGuire’s back porch; photo courtesy Scott McGuire.

And then there are even simpler things, like small pockets for access to things like a point-and-shoot camera that can go in and out quickly, or your lip balm, or that nutritional bar that allows you to get a shot of quick energy. A lot of thought needs to go into where those things go—where pocketing and storage should be, both from an organizational standpoint but also from a load-dispersion standpoint. These are all maybe a little comparable to how an architect might think: it’s about organizing the space, but down to a level of detail that takes into consideration very different people doing very different things with their gear.

Once you’re talking about the load—about what you’re carrying and how that gets managed—the next thing is going to be materials. The materials are so important. Like in conventional architecture and design, materials obviously have an aesthetic appeal. On the business side of it, the value equation is always about cost versus value. For example, there are things that can cost very little but have a very high value based off their perceived benefit: they’re lightweight, durable, attractive. Things can also have a very high cost but not necessarily have a value that the customer perceives, such as highly technical specialized fabrics that may not really contribute a benefit to your average end user. The benefit’s lost. It’s as if you build a house and you install gold pipes—no one sees it. Do they really make the water taste better?

You need to be really careful about those decisions. When you’re talking about the material selection and if somebody has to carry it, then there’s a balance not only in terms of cost versus value, but also around weight versus durability. In a general analysis, you’ve got price, weight, and durability—and, usually, you only get to pick two. You want something that’s really cheap and super lightweight? You give up durability. You want something that’s super durable and incredibly lightweight? It’s going to cost you a lot of money—you give up price.

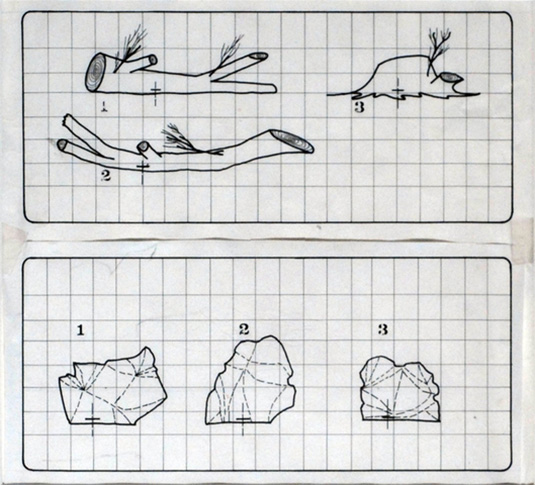

“Ascension of Mt. Blanc” and Glacier of the Rhone.” Photos taken between 1860 and 1890. Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

“Ascension of Mt. Blanc” and Glacier of the Rhone.” Photos taken between 1860 and 1890. Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

To get back to the example of a 40-liter mountaineering pack, that customer typically is investing in a product that is high-quality, with high-durability, designed to take a lot of abuse. And there’s an expectation there that a slightly more expensive product, with greater durability and less failure potential, has higher value. It’s worth the extra money. There’s a huge difference between someone who’s going for their very first backpacking trip versus the person who’s been training for an objective for the last year. That person doesn’t want, after all the hours spent planning, looking at topo maps, and waiting for the weather window, to be hampered by gear. That person’s going to choose quality and durability over price.

Photo courtesy Scott McGuire.

Photo courtesy Scott McGuire.

Manaugh: When it comes to materials, I’m curious if there are things that you or the designers you work with are aware of, that are perfect for certain functions, but they’re so expensive or simply so foreign to the average consumer that the market can’t bear them. In other words, how do you navigate the market with new materials and new designs?

McGuire: One of the Holy Grails here, from a design standpoint, is the side-release buckle. From a functional standpoint, the ability to have a buckle, pop it, have it separate, put it back together, click it, including that audible signal that it’s now secure—that has a simplicity and intuitiveness to it. I think a lot of people in design still look at that and say, gosh, that’s one of the things that’s been around for a long time. But is it the best solution?

It’s always a question of whether you’re building a better mouse trap, or if you’re just trying to do something that’s different—something that’s gimmicky. You’re always balancing what’s unique for the sake of being unique—not necessarily because it’s providing a better solution—versus what’s unique because it’s actually offers a functional improvement.

There are a couple of examples like that. Nobody’s really figured out a better solution than a zipper. But zippers fail; they wear out over a certain period of time. The side-release buckle is a design that is ubiquitous across all packs, and there are different aesthetic treatments to it, but, functionally, they all do the same thing: a two-part click. But there are always people exploring what could be better in that space.

Manaugh: One of the things we talked about a few years ago when I first met you at The North Face was that there are differences in tent design between the North American and the European markets. You mentioned then that, in Europe, campgrounds are so crowded that a different level of privacy is expected from a tent, whereas, in the U.S., you can get away with using much more transparent materials, because you might be the only people at a certain campsite for two or three nights in a row and you don’t need as much privacy.

The REI Half Dome 2 Plus Tent, with and without cover; via REI.

The REI Half Dome 2 Plus Tent, with and without cover; via REI.

I’m curious, now that you’re doing consulting with different companies, different regions, and different markets, how these sorts of cultural differences play out in the design of outdoor equipment in general.

McGuire: The commercial world has gotten a lot smaller, and the ability now to connect with people in those very different cultures has become much more commonplace. That’s true everywhere, I think. I mean, sitting where we are today, we have a lot of people coming through the Eastern Sierra who have traveled all the way from Europe.

I actually just talked to a guy over there in the parking lot on a motorcycle who’s over here from Germany, on his way to Jackson Hole. He said he happened to be swinging by here on his way from Atlanta. I still haven’t figured out the geographical connection to Atlanta, if you’re on your way to Wyoming, but…

Manaugh: [laughs] He was too embarrassed to ask for directions.

McGuire: But it is interesting to see a foreign product in a local environment—you can see where it seems a little odd, and you can try to find out why those little moments are there in the design. There’s also a need to expose yourself to those other places. That means being in Europe and seeing that user; it means being in Japan and seeing that user.

The Big Agnes Copper Spur UL1 Tent with and without cover; via REI.

The Big Agnes Copper Spur UL1 Tent with and without cover; via REI.

Oftentimes, there are unique, local solutions to global problems, and these can influence global gear designs and become ubiquitous. Just as often, there are very specific needs to solve a local issue that are non-transferable. I’ll give you a classic case in point. We just talked about mountaineering in the Eastern Sierras. Well, all of our access is car-based. Everybody drives to a trail head, gets out of their car, and walks up a trail that is highly likely to have no one else on it, and, from there, they end up at the place they’re climbing, and so on. It’s not uncommon for people here to go out and, from the time they leave their car until they bag their peak and come back, they never see anybody—not even a trace of another person.

But in Chamonix, over in France, there’s a parade from 7:00 am every morning. If you sit at the base, where the trail goes up Mont Blanc, you can watch people coming down with their coffee and their croissant, and they’ve got their crampons in the back of their pack. They’ve got all of their gear. They’re going to climb into a tightly packed gondola with 50 or even 100 other people, and that’s all before they even start their climb.

Two photos of architecture on the Aiguille du Midi in Chamonix, France; uncredited; found via Google Image Search.

Two photos of architecture on the Aiguille du Midi in Chamonix, France; uncredited; found via Google Image Search.

So, here, in the Eastern Sierra, you can just say, Jed Clampett-style, eh, my crampons are over here, my ice axe is here, and, as long as my hiking partner isn’t within five feet of me, well—hook, swing—who cares? But when people start getting into a packed tram system in Chamonix, and they’ve all got to scoot together, you really need to start thinking about how you protect all those sharp points. How do you make sure no one’s exposed to those? You’ve got to know where those are.

Those differences are where I think a lot of the challenges are. It’s not necessarily intuitive that something that’s highly successful in one region will automatically have traction in another. Creating a globalized product in a highly specialized market can be very challenging and, oftentimes, there has to be a tolerance. You either have to have tolerance for a broader product assortment to meet regional needs, or you have to accept the fact that you may have a product that’s not specialized enough to hit the local super-user, because you’ve traded off specificity for an ambiguity that will reach more people.

Nicola Twilley: It seems to me that, although in your work you’re responding to the user, the user is also responding to the landscape—so, in effect, you’re responding to the landscape, too. When you look at a landscape, do you more typically see it in terms of what sort of activities you might do there, or are you looking at the landscape from the perspective of the gear you might need?

McGuire: In terms of gear, you do see the differences. I mean, take the west coast of the United States. The climbing conditions for a 40-liter pack in the North Cascades involve a much wetter environment, with much wetter snow and a more volatile climate all around, as far as sudden changes in weather go. But, here in the Eastern Sierra, you can probably plan on the fact that it’s not going to get any precipitation for the next 90 days. You don’t really have to think about bringing a ton of rain gear with you, because we just don’t get storms that show up out of nowhere or weather patterns that suddenly convert. That nuance in meteorological conditions will change what the customer’s wearing, which will change how their pack fits, which will change what they’re carrying, which will change how they store things inside the pack, because of what comes on and off and what they need access to. All those things come into effect.

Then you have geographic nuances—the way the different physical characteristics of the environment that you’re in are going to damage the pack. For example, if you are in a volcanic area, where you’re doing a lot of chimneying, you’re going to end up with a high abrasion area. The impacts of a granite environment and a lot of scree will have a different impact on gear than someone in a classic glacier environment.

So there are geologic elements and there are meteorological elements—and both have an impact on the product itself and an impact on what the user does there. The gear you need in a landscape and the activities you are going to do in that landscape are always going to feed into one another.

Twilley: So you can’t optimize a technical pack for the Eastern Sierra and for climbing in Washington State simultaneously, right? That wouldn’t be the same pack?

McGuire: True. All design at some point is a compromise. If you use vehicles as an analogy, the SUV is the ultimate compromise. It doesn’t really carry everything and it doesn’t drive like a sports car, but it’s still managed to fulfill this niche for people. It does enough things pretty well that it allows them to find their solution in one product. That’s an elusive role for packs. It’s why people who end up being pretty active rarely own one pack—they own two, three, or four of different literages, different weights, different carrying capacities, and different materials.

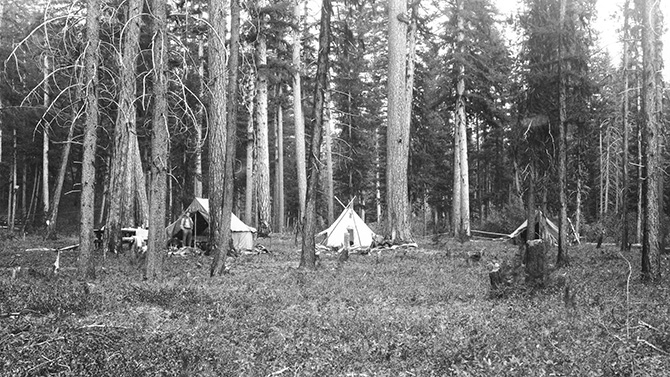

An early U.S. Geological Survey field camp; photo courtesy of the USGS/U.S. Department of the Interior.

An early U.S. Geological Survey field camp; photo courtesy of the USGS/U.S. Department of the Interior.

Manaugh: This is a fairly silly question, but I’m curious if, on a day where you have a lot of free time—you’re lying in a hammock in the mountains somewhere—you ever find yourself thinking that you could design a pack that would be absolutely perfect, but only for a very, very specific place. It would be the ultimate pack for a particular trail in Arizona—but for that trail only. It would be useless in Utah or on a trail in the Alps. And maybe it would cost $5,000—but it’s the perfect pack. Do you have dream gear like that?

McGuire: [laughs, pauses] At the end of the day, that’s what every gear head does. Not just the pack—they’re on the quest for the perfect kit. Unfortunately, what happens is that a large factor in enjoying the outdoor environment is wanderlust. As soon as your kit is perfect in one place, not only does the gear itself change over time or through use, but, usually, your reaction is, “Great! Now that I’ve experienced this, let me go to this other place…” And all of your metrics have been thrown off. You start building the perfect kit all over again. So, as soon as that’s obtainable, your own interest level changes, and it goes away.

Of course, I’m not actually a designer, in that I don’t really put pen to paper. I work on strategy and process, with people who do the pen-to-paper side of things—people who are highly creative and sometimes even have an arts background.

Courtesy Osprey Packs.

Courtesy Osprey Packs.

One of the best examples of that kind of designer, and one of the people I admire the most in this space, is Mike Pfotenhauer, who’s the owner and designer of Osprey Packs. Mike is classically trained as a sculptor so, when you look at Mike’s pack design, there’s an aesthetic to his product that speaks to his ability as a sculptor. It’s very rare that you see straight lines. I’m convinced that if Mike could get someone to weave for him a curved webbing, his packs would all have curved webbing on them. He wants things to have this organic flow, which means there’s a signature to his packs, because he’s only worked on one brand as an owner and designer for his entire career.

Courtesy Osprey Packs.

Courtesy Osprey Packs.

But, when you look at the actual function of his designs, he’s a real user. He’s a backpacker. He doesn’t let his aesthetic override the fact that, as a user, he knows his end product has to work. Case in point: take the webbing. At the end of the day, something needs to be able to pull and compress. If the pieces of webbing that are the most effective at doing that require straight lines to pull, then he knows the pack’s aesthetic needs to give way to the fact that there’s a functional need calling for something different.

Courtesy Osprey Packs.

Courtesy Osprey Packs.

Twilley: Given the importance of the user and the landscape, can you talk a little about how this gear is tested? Are there labs filled with simulated environments where packs are repeatedly rubbed against things, or sprayed with water and then flash-frozen to see what happens?

McGuire: There are three legitimate forms of testing. There’s the ASTM/EN, with the ASTM being the American Standard Testing Method and EN being the European Norm. These are scientific methodologies around proving whether something’s working in the right way. Those are usually at an item level. Then, there are ASTM things around complete packages like insulation warmth ratings for sleeping bags. There are rules around how to properly gauge the square footage and volume of a tent or the volume of the inside of a pack. So these are metrics that can be tested.

On the testing from a durability standpoint, oftentimes it’s specific devices that measure individual materials.

Twilley: Oh, so it’s not the complete pack. You just test a particular buckle, for example.

McGuire: Yeah. You might pull-test the buckle to make sure it can survive a 300-pound pull test. You might take a piece of material and put it on a Taber machine and see how many cycles it takes until the machine rubs a hole through it to see what the material’s abrasion durability is. Or you might do a tensile tear strength test to see how a tear would propagate in a rip-stop and how functional the rip-stop is.

These are functional tests that are relatively close to reality, but then there are also reality tests. The classic example of that is a lot of factories and companies will have access to things like very, very large commercial dryers; somebody has taken the time to open them up and bolt 2x4s and climbing holds and all kinds of stuff to the inside of the dryer. Then you throw a pack or a piece of luggage onto it, turn the dryer on, and let it just beat the daylights out of something till you see where your failures are.

Or you’ll have jerk tests on handles, where you’ll have a weight that—over and over again—will simulate the grabbing of a shoulder strap with a 60-pound pack and throwing it over your shoulder. What does that do to that seam? You’ll simulate it over and over again, and you’ll see, as you grab the shoulder strap and yank on it, if you yank a little this way or you yank a little that way, you end up putting different seam stresses on each place.

These sorts of reality-based testing devices are, oftentimes, custom manufactured. They’re not necessarily scientific. They’ll run through the cycles so that you see where there need to be improvements, but there’s not really a standardized test to measure it against.

But, still, today, in this industry, nothing beats human use.

Twilley: You mean field-testing?

McGuire: Product failures in this space are rarely attributable only to one thing. It’s almost always systematic. For instance, the shoulder strap didn’t fail because it was getting pulled up and down; the shoulder strap failed because of the way it was stitched, and then the way it was worn by the user, which created a spot where it sat on the shoulder blade, and that wore the stitching down over the course of a 600-mile trip, which then exposed the motion to a failure. An abrasion test on its own or a jerk test on its own wouldn’t expose that, but, in real world use, those two things combined expose a weakness. This is where human testing really is the quintessential component to make sure things work right.

This is also why so many people in design—in fact, every single person I know who was an inventor of an outdoor product in the 50s and 60s, during the real heyday of our industry—came into prominence not because they were designers. They were users who, by necessity, turned to design to solve a problem.

Image courtesy of Skipedia.

Image courtesy of Skipedia.

This is how Scot Schmidt created the original Steep Tech gear for North Face. Scot didn’t want to be a clothing designer—at least, from everything I heard from him. Scot just wanted to be a skier who didn’t have to deal with duct taping his knees and shoulders because he was skiing in such horrendous conditions and he kept tearing the fabric.

The original North Face Mountain Light jacket with its “iconic black shoulder”; photo courtesy ZONE7STYLE.

The original North Face Mountain Light jacket with its “iconic black shoulder”; photo courtesy ZONE7STYLE.

The iconic black shoulder of the original North Face Mountain Light jacket came about not because someone thought, “Wow, straight lines and bold blocking is going to look awesome.” It came about because someone said, “I need a super-durable material because, when I throw my skis over my shoulder to hike up this ridge, the straight skis of the 1970s and 80s rub a hole through my jacket”—and the only thing available at the time was a 1680 ballistic nylon that only came in black because it was for the military.

You end up with an iconic design that was never intended to be an iconic design. It just happened that way because of a specific need, and it evolved to become an icon.

Photo courtesy The North Face.

Photo courtesy The North Face.

Twilley: Are there landscapes that gear innovation has opened up, in a way? Obviously, there are extreme landscapes, like Mt. Everest or Antarctica, where the right gear can be the difference between making it or not, but are other types of landscapes now opening up through innovations in outdoors gear?

McGuire: For sure. I think ever since people started pushing the limits of where they could survive, the types of landscapes available to people have changed. There are the extremes, like you mention, of being up in the Himalayas—up at high altitude—where gear has had an absolutely huge impact. But I would say that one of the challenges in our industry has actually been that, for the most part, for better or worse, most of the impacts on design from extreme environments happened more than a decade ago.

What’s happening today, I think, that’s now driving some of the greatest innovation aren’t the extremes of the environment, but what people are trying to do in that environment on either end. It’s the book-ends of either extreme. In other words, design is being driven now by people who are going much farther, much faster, and much harder than they ever did before.

Take the idea of building a product for hiking the Pacific Crest Trail—which is 2,400 miles. Typically, that would take four to six months—and, in 1970 or 1980, that was a pretty extreme environment. Now, that environment hasn’t really changed—there’s global warming, of course, so there have been changes in the glaciers and so on—but, effectively, that trail is the same as it was for the past forty or fifty years. What has changed now is that people are coming in and saying: “I want to do the entire Pacific Crest Trail, and I want to do it in ninety days. Instead of doing eight to ten miles a day, I want to do twenty-five or thirty miles a day.” In order to do that, people who were comfortable with carrying a 60-pound pack on the trip are now saying that there’s no way they’d go out there with more than 30 pounds. In fact, on the far end of that, people are saying they should be perfectly comfortable, and fully safe and functional, with only a 15-pound pack. Put all that together, and that necessitates a new kind of design.

“Aletsch Glacier“; “Lac des Morts, Grimsell“; and”Aletsch Glacier, Eggischorn.” All photos taken between 1860 and 1890. Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

“Aletsch Glacier“; “Lac des Morts, Grimsell“; and”Aletsch Glacier, Eggischorn.” All photos taken between 1860 and 1890. Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

But there’s also the other extreme. We have a society that is spending less and less time in the outdoors. What we’re finding, on the other end, is that the goal is to just make sure the approachability of the outdoors is simple enough, and convenient enough, and affordable enough, that, when people are trading a weekend in front of their Wii for a weekend taking their family camping on the side of a river, that it’s not intimidating. It’s not scary. For instance, how do you design a tent for someone who’s never set up a tent before, or who thinks a tent is so expensive that it’s a barrier to entry? A tent that’s not so complex that I can’t even imagine using it? Or a tent that’s not so small that I can’t stand up and change my clothes? What does that look like?

So you have these very divergent activities, these very different spaces, but, in each one, you have people who basically need something—they need a piece of gear or equipment—that can allow them to have this experience. That’s where I think most of the innovations have come from in the last decade. It’s not the middle ground. It’s these extreme fringes on either side.

Manaugh: Do you find, ironically, that the guy who wants to be home playing Wii all day in the suburbs is actually the more challenging design client?

McGuire: Well, let me back up a bit. If you go to a company like Procter & Gamble, for example, you find people there who are working as industrial designers, and they’re trying to think like a customer who they just might not be. But, in this industry, you have people who are really just trying to solve their own problems, in their own tinkering way.

Photos courtesy of the Outdoor Retailer show.

Photos courtesy of the Outdoor Retailer show.

The Outdoor Retailer trade show is a very unique environment, in that regard. It’s like a tribe. You walk into that outdoor retailer environment and, if you’re in the outdoor industry, you can see straightaway who’s there and who’s not there—meaning, who’s part of the tribe and who’s a visitor. It’s a group of a lot of the same people, over decades now, doing a lot of the same things. You might see different companies and different brands over time, but what you don’t see is a lot of people from outside of that space showing up there. If you’re an outsider and you show up—if you’re trying to pose like you’re there, and trying to sell into that space—that group smells your inauthenticity right away. But, now, this tribe mentality is starting to recognize that the future of the industry is outside of our own doors. In fact, not enough people are finding their way into the tribe on their own and we have to bring in more people.

Photos courtesy of the Outdoor Retailer show.

Photos courtesy of the Outdoor Retailer show.

So the industry itself has been wrestling with this. How do we go out and approach someone? I’ll use an analogy. In the industry, there have been three rings of people: there’s your hardcore ring of people who are absolute purists: “I make it all myself. And I’m so badass, no one even knows where I go.”

They’re almost elitist in their pursuit of their sport. But then you have another side, which is a group of people who like the outdoors, but they’ve recognized that there’s commercial value there. They are mostly driven by the business side of it. They’re people who want to work in the outdoor company sector because they like the idea of going to work in a T-shirt and jeans, versus wearing a suit, and their skills lend themselves to this space, but you also kind of know that a person like that isn’t really from here because their core motivation is: “Wow, we can make money off of this!”

So the ex-suits don’t get the hardcores, and the hardcores resent the fact that all these ex-suits are showing up. Then there’s this tiny group in the middle who are interested in the business side, but they also come from the hardcore side at one point—and, what’s interesting is that all of these people in this group of three circles in the industry right now are wondering: “Who’s going to come in from outside our three circles? Who’s going to drive the business going forward? Who are those people?”

Photos courtesy of the Outdoor Retailer show.

Photos courtesy of the Outdoor Retailer show.

There were some good industry numbers that came out recently where, for the first time, we’re seeing the number of young people getting exposed to the outdoors is on a slight uptick. I would say it’s encouraging news. It’s not good news, because we still have a long way to go. But, from a design standpoint in the industry, that’s something that appeals both to the suits—“Wow, new customers! More money!”—and also that center group, along with the old hardcores, who love seeing the interest and the energy grow. They all see that, from a culture standpoint, we need this: the stronger our tribe is—the more people who come into it—the better it’s all going to be.

But I have a love/hate relationship with some of the solutions that have come up in the past few years. Here, in the Eastern Sierras, we have a pretty robust program where you can get on the phone in Los Angeles and call a company that will deliver a camping trailer to a campground here for you. You drive up in your little economy car from the city, and you pull into a campground, and the there’s this 26-foot trailer sitting there waiting for you, with all the comforts of home. It’s got a mattress; it’s got running water; it’s got a toilet; the refrigerator is eve pre-stocked. The stoves are there. There’s propane in the tanks. It’s like a pop-up hotel.

The “love” part of me is that more people are now actually making the trip. It’s like a gateway drug. Somebody who might not have got in their car is at least opening their door at 6:00 in the morning and smelling trees and not being in a parking lot at a hotel somewhere. So it’s a start.

The difference, though—the “hate” part of me—is that there’s nothing like being out there in the dark, putting a tent up, finding a site. You know, maybe I’m a little bit of a sadomasochist in this regard. But, for me, when you’re in the outdoors, tripping over the picnic table and trying to figure out where the guylines go, and dropping stakes and wondering if you remembered to put them all in… Not that I want to see people suffer! But part of it is actually about the dirt under the fingernails—it’s that sharp rock under the tent that keeps you awake at night.

But, as long as people are making the trip, and, from a design standpoint, as long as we’re making a product that eases that transition for people as much as possible…

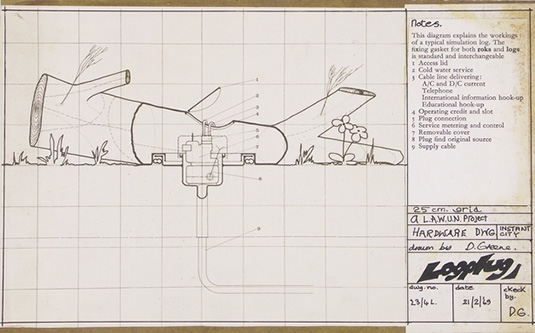

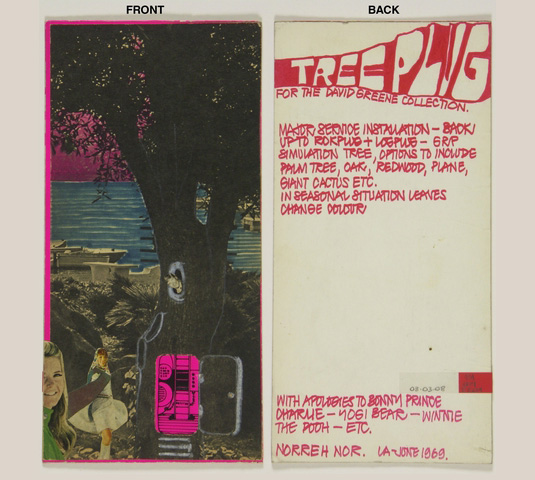

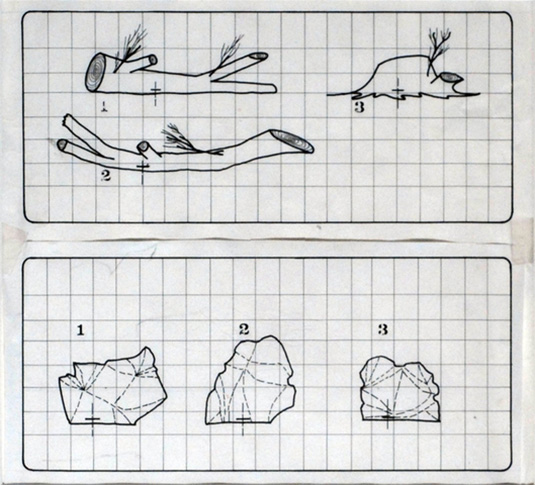

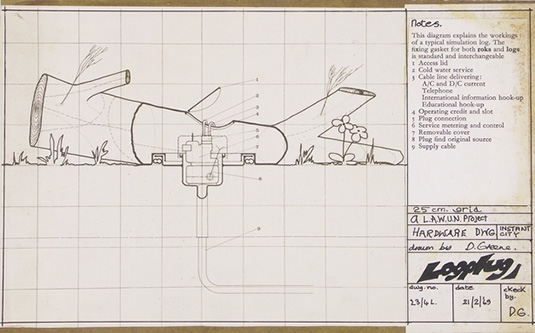

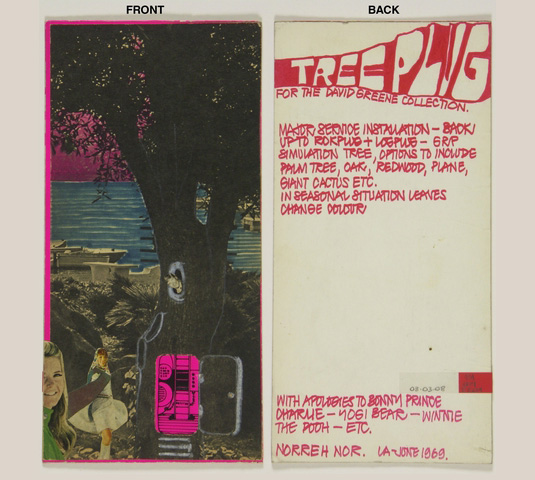

The LogPlug and RokPlug projects by Archigram, courtesy of the Archigram Archival Project at the University of Westminster.

The LogPlug and RokPlug projects by Archigram, courtesy of the Archigram Archival Project at the University of Westminster.

Manaugh: It’s funny, your trailer example actually reminded me of this group of architectural designers in England in the 1960s/early 70s called Archigram. They were somewhere between science fiction and Woodstock. They had this one series of designs—and it was all totally speculative—for fake logs with electrical outlets that could be put out in the woods somewhere, and even fake rocks that could act as speakers, and so on.

The LogPlug and RokPlug projects by Archigram, courtesy of the Archigram Archival Project at the University of Westminster.

The LogPlug and RokPlug projects by Archigram, courtesy of the Archigram Archival Project at the University of Westminster.

But the funny thing is that the intention of the project was to get more people in 1960s England out of their middle-class houses and into the wilderness, to experience a non-urban environment. Of course, though, the perhaps unanticipated side effect of a proposal like that is that they were actually just extending the city out into the woods, letting you take all these ridiculous things, like TVs and toasters, in the great outdoors with you, things that you don’t ever really need in that environment in the first place.

The LogPlug and RokPlug projects by Archigram, courtesy of the Archigram Archival Project at the University of Westminster.

The LogPlug and RokPlug projects by Archigram, courtesy of the Archigram Archival Project at the University of Westminster.

In other words, it seems like an almost impossibly thin line between enticing people to go out into a new environment versus simply taking their ubiquitous home environment and infecting someplace new with it. The next thing you know, the woods are just like London and the Eastern Sierra are just like Los Angeles.

REI’s portable, pop-up, outdoor Camp Kitchen. Are outdoor equipment manufacturers the true inheritors of Archigram‘s speculative design mantle?

REI’s portable, pop-up, outdoor Camp Kitchen. Are outdoor equipment manufacturers the true inheritors of Archigram‘s speculative design mantle?

In any case, I wanted to return to something you said earlier about ballistic nylon materials that had originally been developed by the military. Are you still finding materials and technical innovations coming out of the military that can be “civilianized,” so to speak, for use by outdoors enthusiasts? For instance, I recently read that the military has developed silent Velcro, which seems like it could be useful for backpackers.

McGuire: Definitely, yes. On the military side of things, what’s different now, is that, except on very rare occasions, people today are not humping huge loads over long distances to fight wars. Soldiers are now incredibly mobile. They’re vehicle-based; they move in; they move out; they carry just what they need; they get the job done; and they’re gone. We have a lot of people coming back from wars today—and I’m not at all taking away from what they’re doing—but their war experience is unlike even just a few generations ago, where you put your pack on and everything you needed was in your pack and you were gone out in the wilderness somewhere for a year. We increasingly have soldiers who get in a Humvee, go out for a day, maybe two days, and then they’re back at base.

“New York Central Issue Facility Strives to Get National Guard Troops Latest Gear.” Image and caption courtesy of the U.S. Army.

“New York Central Issue Facility Strives to Get National Guard Troops Latest Gear.” Image and caption courtesy of the U.S. Army.

What I think we’re seeing, culturally, is a lot like this. The patience for long-term adventures is waning. People want to go out and have an experience. They want it to be quick. They want it to be impactful. They want it to be memorable. And, to be honest, they want it to be easy. It’s the “I want to see Europe in five days and here are all my pictures” thing. It’s speed and efficiency. Well, one area where the military is lending some benefit is that they’re developing a lot of specialized gear for these in quick/out quick, intense experiences. You’re seeing things like the MOLLE system—what is it, Modular, Lightweight, Load-carrying Equipment?—and that modularity is seeping out of the military to influence outdoor gear design, where you’re able to have a base system that can increase or decrease in size, depending on the specifics of your day and what you’re going to go out and do. These are influences that that are now starting to show up.

“The Army is able to swiftly deploy soldiers where they’re needed and part of that is ensuring soldiers are properly equipped. The materials they need-they need fast, and that’s where a rapid fielding initiative team comes in.” Image and caption courtesy of the U.S. Army.

“The Army is able to swiftly deploy soldiers where they’re needed and part of that is ensuring soldiers are properly equipped. The materials they need-they need fast, and that’s where a rapid fielding initiative team comes in.” Image and caption courtesy of the U.S. Army.

And there are some strong crossovers, in things like hydration, that are now becoming much more ubiquitous. We aren’t seeing that crossover quite as influentially as the original A-frame tents, or the development of sleeping bags coming out of World War I and World War II, but we’re certainly still seeing it. But I would say that the most significant recent impact are things like GPS—highly specialized technical solutions that make things work much better and much easier, and that don’t take up a lot of space.

GPS is military-based, and the ability to know where you are, where you’re going, and how to get back, without having to rely on map knowledge, has opened up all kinds of confidence for people to get into new places. Personally, I love using a GPS, but I still think you ought to know which way north is and how to read a map—because batteries die.

We’re also still seeing new materials come out of the military, like super-lightweight parachute fabrics that are allowing people to have highly tear-resistant, lighter-weight equipment. And, even with helmets, the foams used in lighter-weight, highly protective helmets are changing, mostly as a result of IEDs.

Combat helmets with sensors attached are part of “the next generation of protective equipment” for the U.S. Army. Image courtesy of the U.S. Army.

Combat helmets with sensors attached are part of “the next generation of protective equipment” for the U.S. Army. Image courtesy of the U.S. Army.

So, yes, we are seeing elements of the military trickle into outdoor gear. I just think that, with the needs of the military being what they are today, and the way that wars are being fought now, it just happens to serendipitously fall in line with a cultural desire for short, fast, light outdoors experiences—you’re done and you’re back. It is a bizarre overlap, but you’d be hard-pressed to say it’s attributable to one or the other.

Manaugh: To build on that question of cultural shifts, when you said that more kids are starting to go outdoors, I immediately wondered if at least part of that is due to a pretty huge rise in popularity of things like alternative sports: X Games, BMX, skateboarding, and so on, all those urban subcultures that I grew up with, but that had no real media attention at the time. They’re now becoming more and more mainstream. I suppose my question is: is the city its own form of “outdoors” now, and are alternative urban sports a kind of indirect way of getting kids interested in forests, or rock-climbing, or going bouldering?

Twilley: I might even add to that, to speculate that kids exploring sewers or breaking into abandoned steel mills are perhaps experiencing the same kind of thrills that the first generation of outdoors enthusiasts did in the West. Is urban exploration the next big opportunity for gear in the future, given our increasingly urbanized world?

McGuire: I think I’d say yes to both. Something that’s endemic to the outdoor industry is, first and foremost, the idea of having an experience. It’s about stretching where your comfort level is. So I would say pick whichever sport you want—skate, snowboard, mountain bike—those sports have allowed people to stretch what they believe they’re capable of. Whether you think that what people are doing on the west shore of Vancouver with mountain biking, and pushing the mountain biking free-ride space, is good or not, at the end of the day what we have is a generation of people who are having an experience that’s not inside of four walls. They’re pushing their comfort levels, and they’re having an experience and a memory that involves fresh air.

Martin Söderström in a timelapse jump, courtesy of Red Bull.

Martin Söderström in a timelapse jump, courtesy of Red Bull.

What we’re seeing among the youngest generation today is there is much less identity around sport specificity. I’m almost 40. When I grew up, you were a surfer or you were a skater or you were a climber or you were a road biker. But kids today don’t think anything like that—they think, “I do all of those things!” Why would I not be someone who is a skier who’s also into bouldering who’s taking up trail running and who competes in Wii dance competitions? Why can’t I be that person? There’s a sense that I will be whoever I want to be, whenever, and of course I will be multifaceted.

When we start talking about trying to build gear for those kids, you want to make sure that the gear allows them to do the current activity—and that might be more urban-influenced, like skating and biking—but, as they grow and stretch, it isn’t a hindrance to their next thing. Does your free-ride hydration pack let you try trail running? I think people are discovering on their own where their next challenge is, but the way they’re discovering it, and the tools they’re using to discover it, aren’t yet in the view of the popular side of the industry.

Spanish freerider Andreu Lacondeguy from Where The Trail Ends; photo by Blake Jorgenson for the Red Bull Content Pool, courtesy of Red Bull.

Spanish freerider Andreu Lacondeguy from Where The Trail Ends; photo by Blake Jorgenson for the Red Bull Content Pool, courtesy of Red Bull.

I’ll give you an example. I live in a place just down the road from here called McGee Canyon. It’s a beautiful canyon. I was going for a trail run the other morning; it was relatively early, about 7:30 in the morning, and I see these kids walking toward me. The guy is in jeans, Vans, his hat’s cocked off to the side; he’s got a hoodie, a t-shirt. It’s got some outdoor qualities to it, but it’s got some hip graphics. Kind of unshaven. He could just as easily have been walking down the street in the Mission District. His girlfriend’s in Toms shoes with knee-high, super bright-colored stockings, board shorts, a hoodie, big sunglasses, a hat. A very, very unlikely couple to see walking down this trail at sunrise. It was kind of surprising.

Photos courtesy of Poler.

Photos courtesy of Poler.

I actually stopped running and I said, “Hey, where are you guys from?” They’re from Los Angeles. What they’d done is they’d taken their iPhones and they’d decided to go for a hike up to a place and take some Instagrams of waterfalls and flowers with their phones to share with their friends.

Photo courtesy of Poler.

Photo courtesy of Poler.

So, are they hikers? I mean, she’s hiking in a pair of Toms and knee-highs, which are not really hiking products. But this is a generation who don’t see why they can’t leave the trail, go to town, have lunch, and go to the skate park and skate all afternoon, and not change gear. But the outdoor industry is having a hard time reconciling that.

Photos courtesy of Poler.

Photos courtesy of Poler.

How do you talk to a customer who is that different from us? There is, right now, in the industry, a huge generational gap where most of the people in the industry, culturally, simply don’t understand their audience. What we’re seeing out of that is that new brands are starting to emerge that are able to translate the surf-skater or the city-hipster culture into this interest in outdoor experience in unique ways. Brands like Poler out of Portland, or Alite in San Francisco, with Tae Kim: these guys are actually starting to create brand identities that appeal to a customer that the outdoor industry still doesn’t get… You know, the outdoor industry has always tried to say, “Come to us!” And Poler and these other guys are saying: “We make a product that’s coming to you and to your aesthetic.”

Photos courtesy of Poler.

Photos courtesy of Poler.

Twilley: Is figuring out how to serve that new kind of customer part of the work you do with Mountain Lab?

McGuire: What I’ve been doing is working with companies that know they need something, but they aren’t quite sure what it is yet. Of course, I don’t necessarily have all the answers for them, but my job is to help assemble the right teams of people—to find the people who can work on and solve that problem. I rely very heavily on a vast network of people: people who are professors of ethnography and cultural anthropology, people who are designers in Sweden and have a background in a very clean aesthetic, and people who are, you know, hipster skaters into trail running who live in New York City.

How do you take those people and put them together on a team with a common problem? Here’s the designer who has the right aesthetic, something that matches the brand value, and here’s the ethnographer who can say that this is who the customer is today, and this is what the design experience will need to look like, from a marketing standpoint, to communicate something to that customer.

The “lab” part of Mountain Lab is really the assembly. What are all the things that go in the pot to make the special sauce? It’s putting those things together.

Twilley: And what’s the product at the end? A recommendation? A prototype?

McGuire: It’s a mix of things. We’ve done things as simple as assembling business plans for startup companies, so they can go out and receive their second or third level of funding, to actually creating design briefs and pricing metrics, all the way through to completed design packages presented back for line review. Our main focus is not just what the solution is now, but what the solution will be—how things are changing, and how you know what customers need—that incremental step of asking “What does this look like in phases A, B, C and D?”

Manaugh: Finally, how does the internal structure of Mountain Lab work?

McGuire: It’s a revolving door. I’m the only constant within the Mountain Lab today. I would say that there are eight to ten people who, on any given week, are part of my regular repertoire of who I go to. Some I go to more than others, but, at this point, everyone is independent.

In Steven Johnson’s book, Where Good Ideas Come From, he talks about the coffee shops of the Renaissance period. For me, a lot of what Mountain Lab is about is having that kind of network of people—I know that I want to have these eight people around the coffee table to share ideas. And, on the next project, or even the next phase of the same project, it might be that these four need to stay, but then we need fresh insight from these other four. And we keep changing it up. There are times where I’m not part of the conversation at all. I may be introducing two or three people, setting the stage for their dialogue, but then just taking what they’ve reported back out and adding it into another dialogue next year.

That’s part of what allows me to live in the Eastern Sierra. I live in the middle of nowhere, where nobody I work with lives, but I also live in a place that, in my industry, is deeply rooted with all the customers I work with. So technology allows me to move well beyond the Eastern Sierra, but my proximity to the end-user here allows me to stay really focused on being close to what they do and what they need.

I didn’t think, though, when I started the Mountain Lab, that it was going to be quite the way it’s been. I thought there would be a lot more design work being done in-house with people. The virtual nature of the teams, and the success we’ve found in that virtual collaboration, has surprised me. I’ve also been really surprised—pleasantly surprised—by the people I’ve been able to connect with. I didn’t, in my wildest dreams, ever think I was going to have some of these opportunities twenty years ago, when I first got into the outdoor industry.

I remember going to the very first Outdoor Retailer show with a close friend of mine, walking through the doors, and looking around, and feeling like a kid in a candy store. Now I have friends in those companies, and I can call up these industry legends and say, “Hey, I’m working on this new idea. What do you think?” Or, “Do you know the right person? Where would you go?” I’m so grateful for that opportunity, and for being able to keep that creative stoke alive.

• • •For more

Venue interviews, on human interactions with the built, natural, and virtual environments, check out the

Venue website in full.

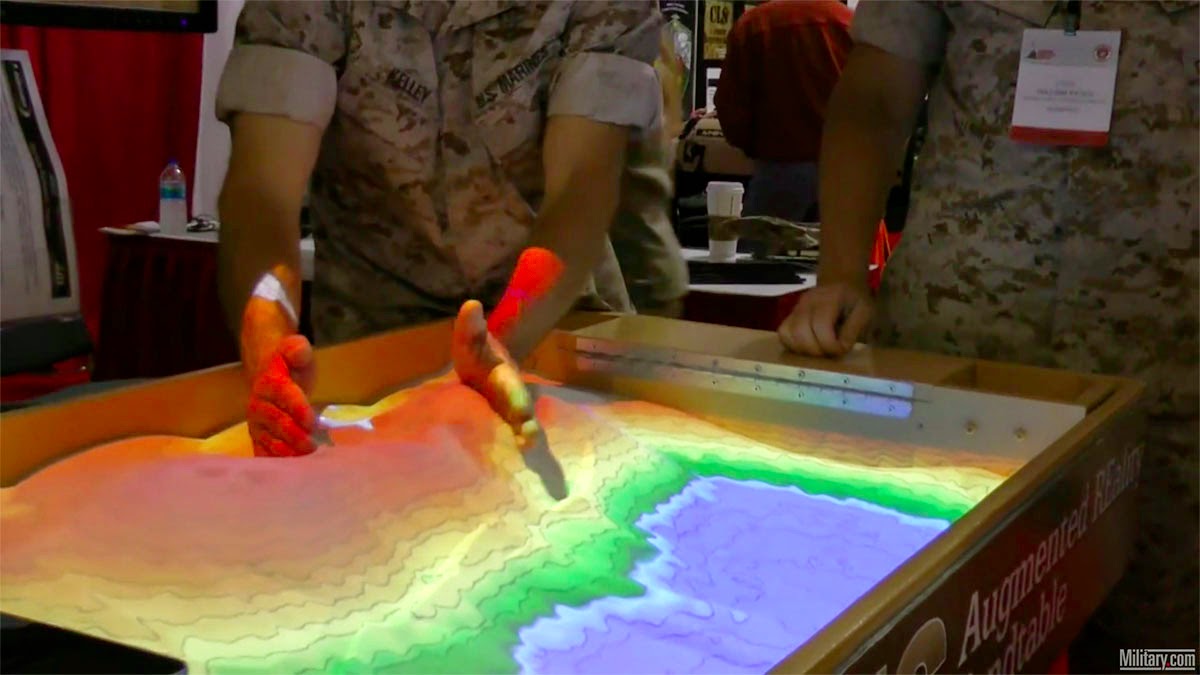

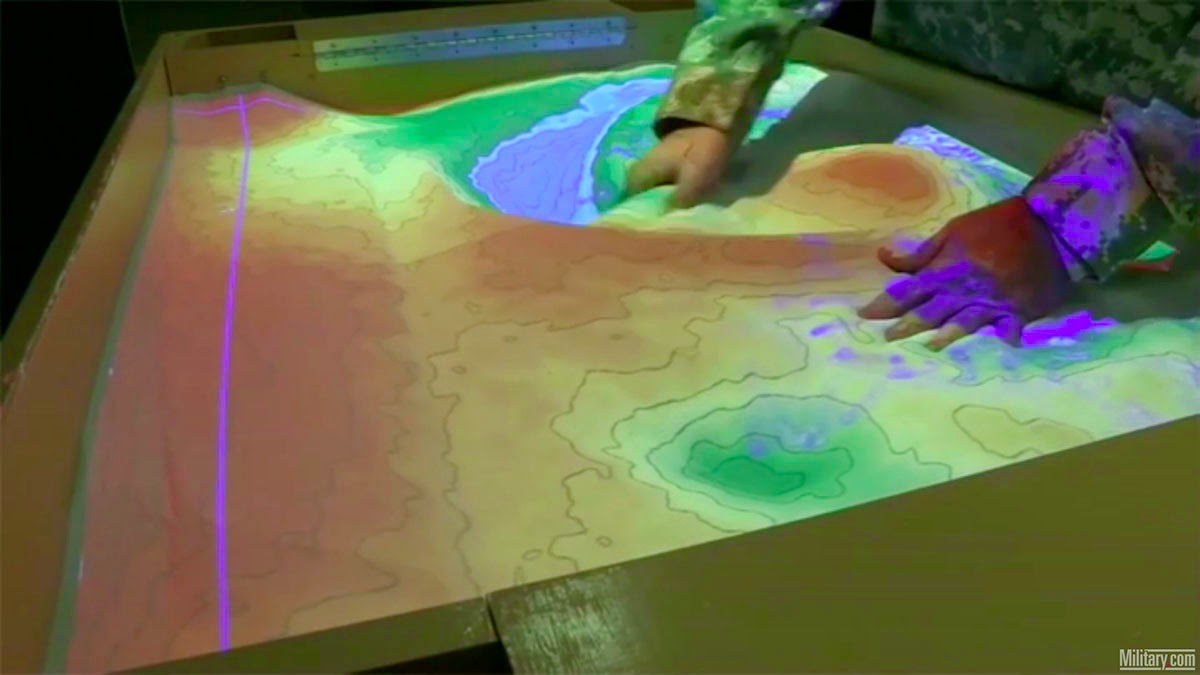

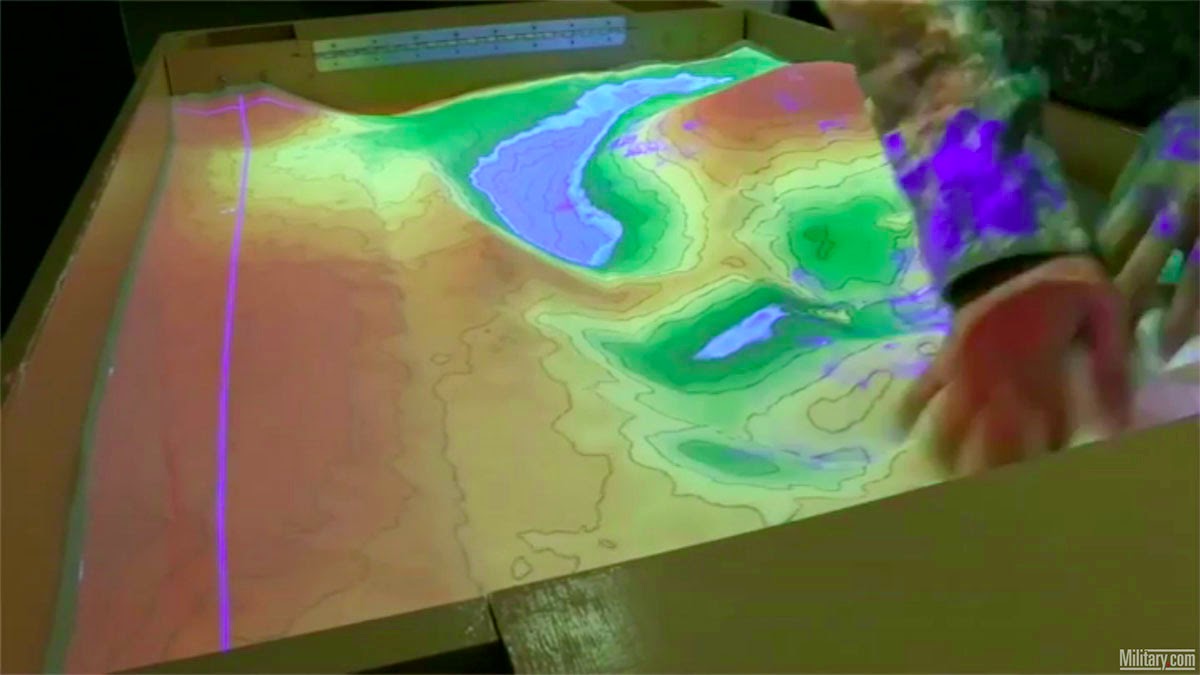

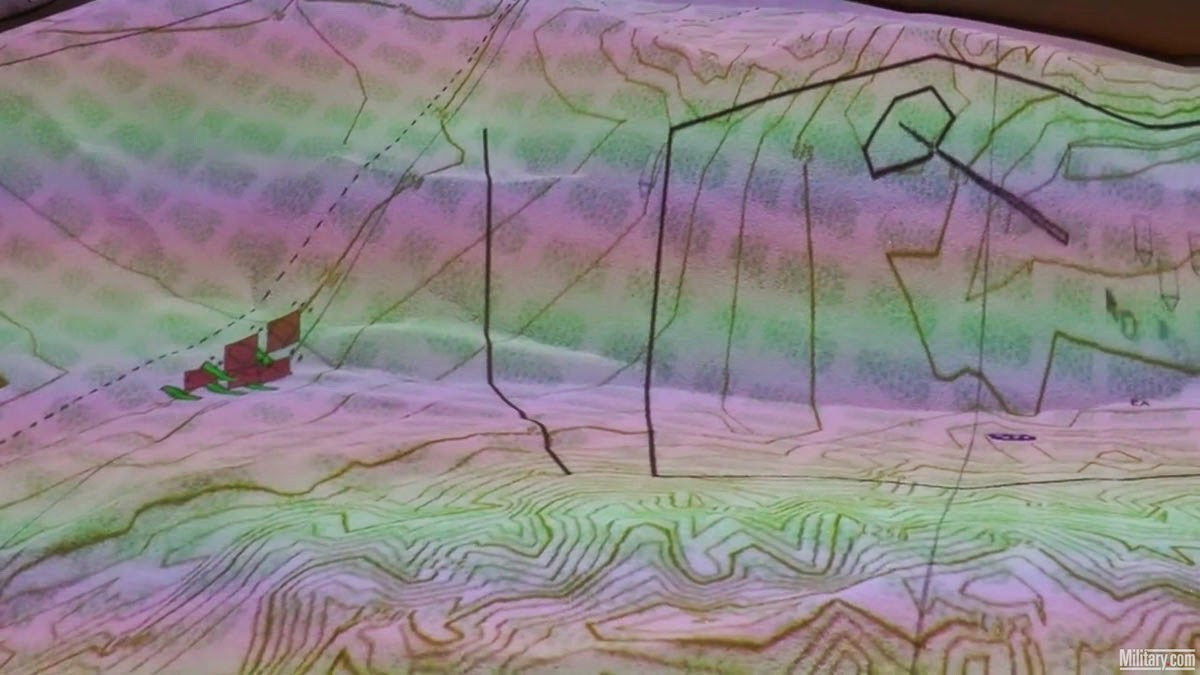

[Image: Screen grab via military.com].

[Image: Screen grab via military.com].

[Image: Screen grabs via military.com].

[Image: Screen grabs via military.com].

[Image: Screen grabs via military.com].

[Image: Screen grabs via military.com].

[Image: Screen grabs via military.com].

[Image: Screen grabs via military.com].

[Image: “Humvees are stored inside the Frigaard Cave in central Norway. The cave is one of six caves that are part of the Marine Corps Prepositioning Program-Norway, which supports the equipping of Marine Expeditionary Brigade consisting of 15,000 Marines and with supplies for up to 30 days.”

[Image: “Humvees are stored inside the Frigaard Cave in central Norway. The cave is one of six caves that are part of the Marine Corps Prepositioning Program-Norway, which supports the equipping of Marine Expeditionary Brigade consisting of 15,000 Marines and with supplies for up to 30 days.”  [Image: “Rows of front loaders and 7-ton trucks sit, gassed up and ready to roll in one of the many corridors in the Frigard supply cave located on the Vaernes Garrison near Trondheim, Norway. This is one of seven [see previous caption!] caves that make up the Marine Corps Prepositioning Program-Norway facility. All the caves total more than 900,000 sq. ft. of storage space, full of enough gear to outfit 13,000 Marines for up to 30 days.”

[Image: “Rows of front loaders and 7-ton trucks sit, gassed up and ready to roll in one of the many corridors in the Frigard supply cave located on the Vaernes Garrison near Trondheim, Norway. This is one of seven [see previous caption!] caves that make up the Marine Corps Prepositioning Program-Norway facility. All the caves total more than 900,000 sq. ft. of storage space, full of enough gear to outfit 13,000 Marines for up to 30 days.”  [Image: “Medium Tactical Vehicle Replacements, High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicles and trailers, which belong to Marine Corps Prepositioning Program-Norway are staged in a storage cave at Tromsdal, Norway, Feb. 24, 2014. Marine Corps began storing equipment in several cave sites throughout Norway in the 1980s to counter the Soviets, but the gear is now reserved for any time of crisis or war.”

[Image: “Medium Tactical Vehicle Replacements, High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicles and trailers, which belong to Marine Corps Prepositioning Program-Norway are staged in a storage cave at Tromsdal, Norway, Feb. 24, 2014. Marine Corps began storing equipment in several cave sites throughout Norway in the 1980s to counter the Soviets, but the gear is now reserved for any time of crisis or war.”  [Image: “China: ample space for a spare copy of France”; image by

[Image: “China: ample space for a spare copy of France”; image by

[Image: A replica of the Nazis’ Atlantic Wall defenses in Scotland; photo via

[Image: A replica of the Nazis’ Atlantic Wall defenses in Scotland; photo via  [Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via

[Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via  [Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via

[Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via  [Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via

[Image: A replica of the Atlantic Wall in Scotland; photo via

[Images: An Atlantic Wall replica in Surrey; top photo by

[Images: An Atlantic Wall replica in Surrey; top photo by

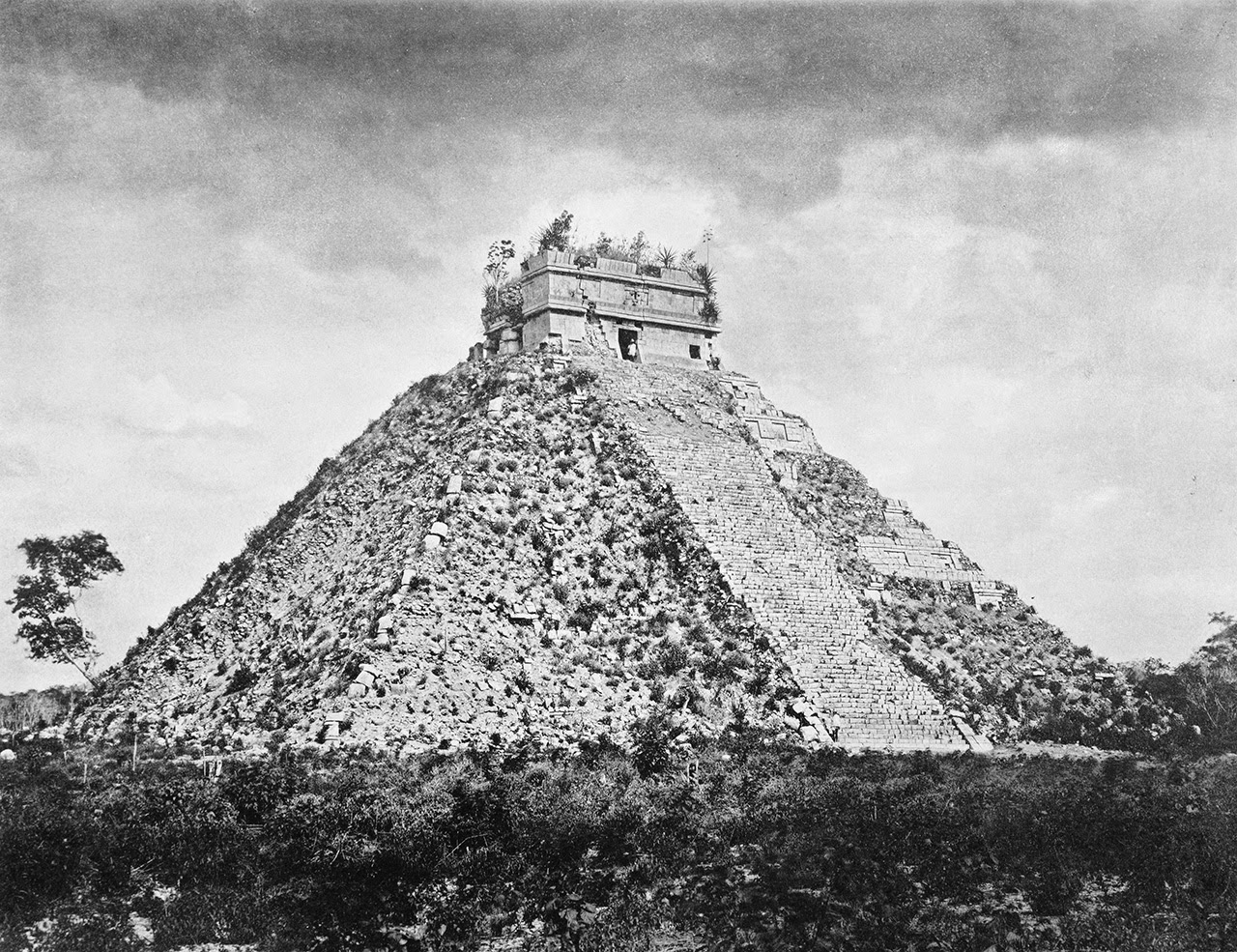

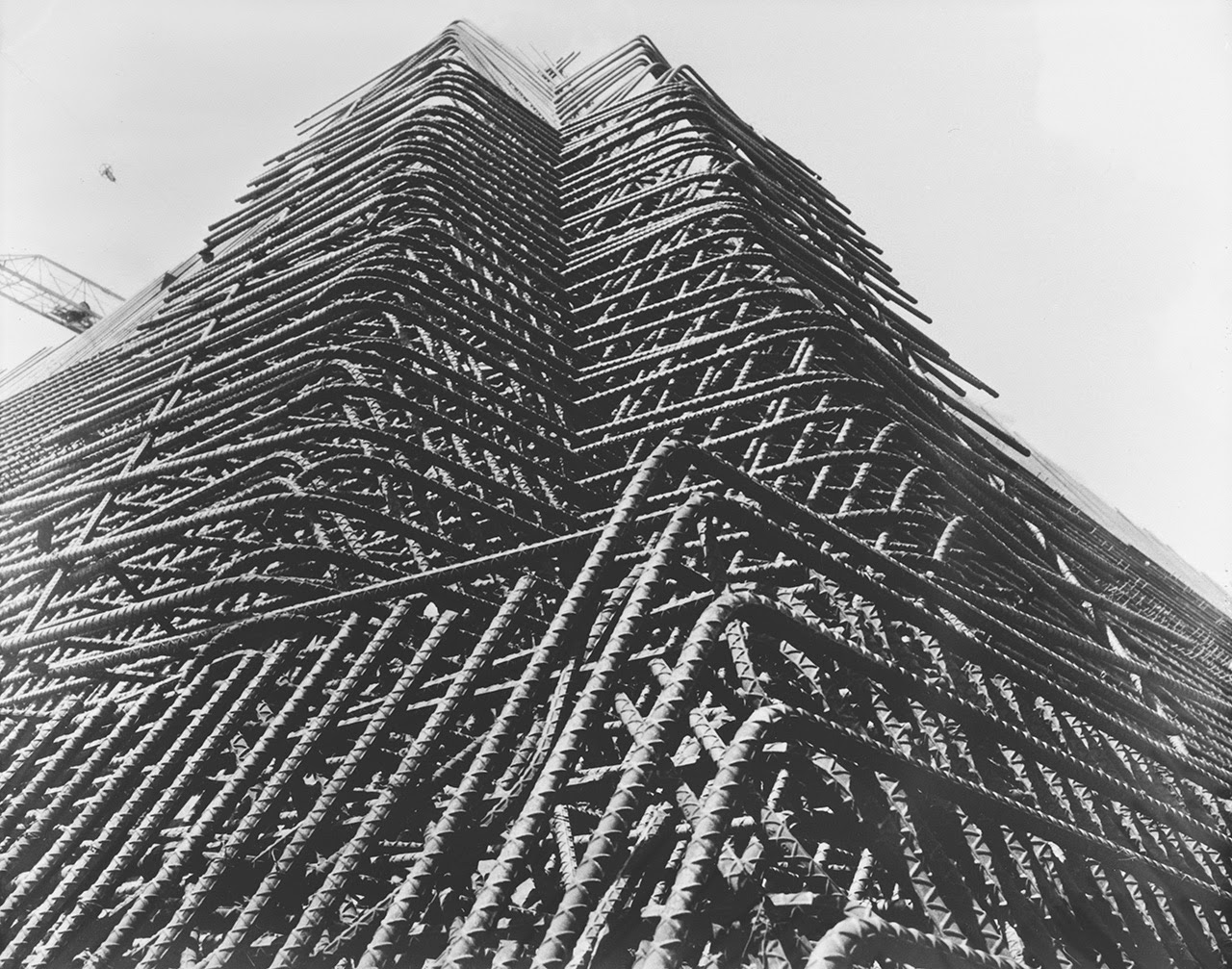

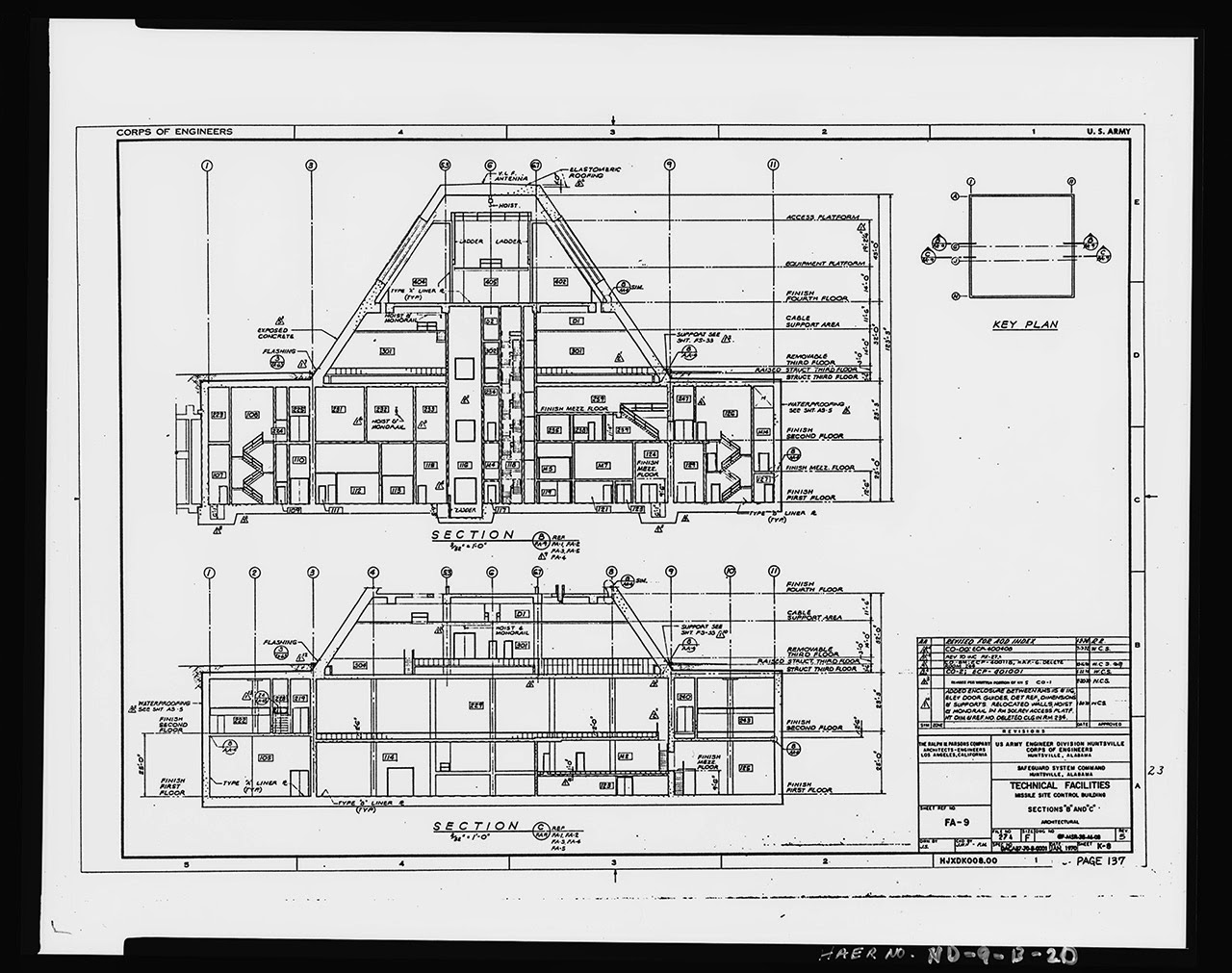

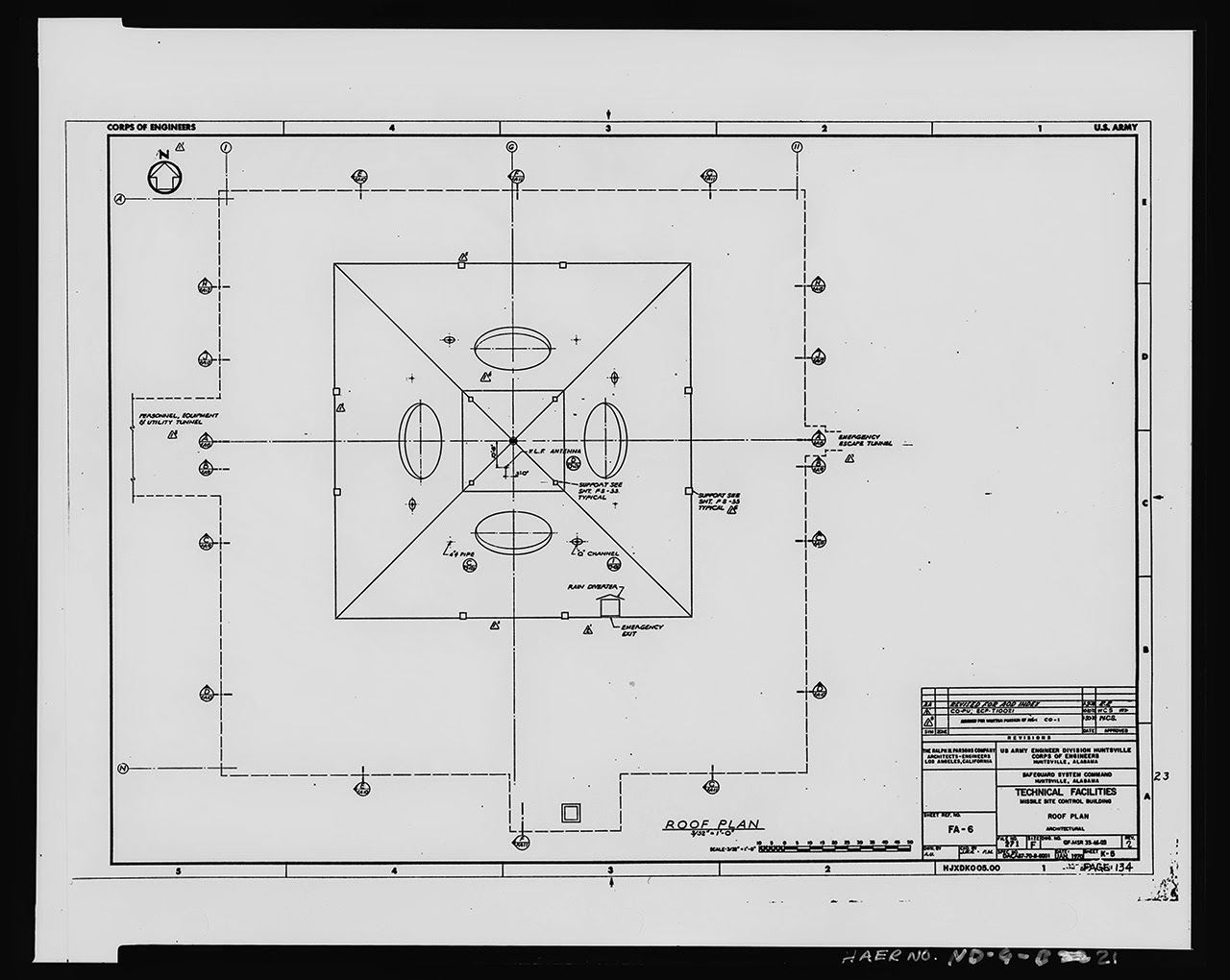

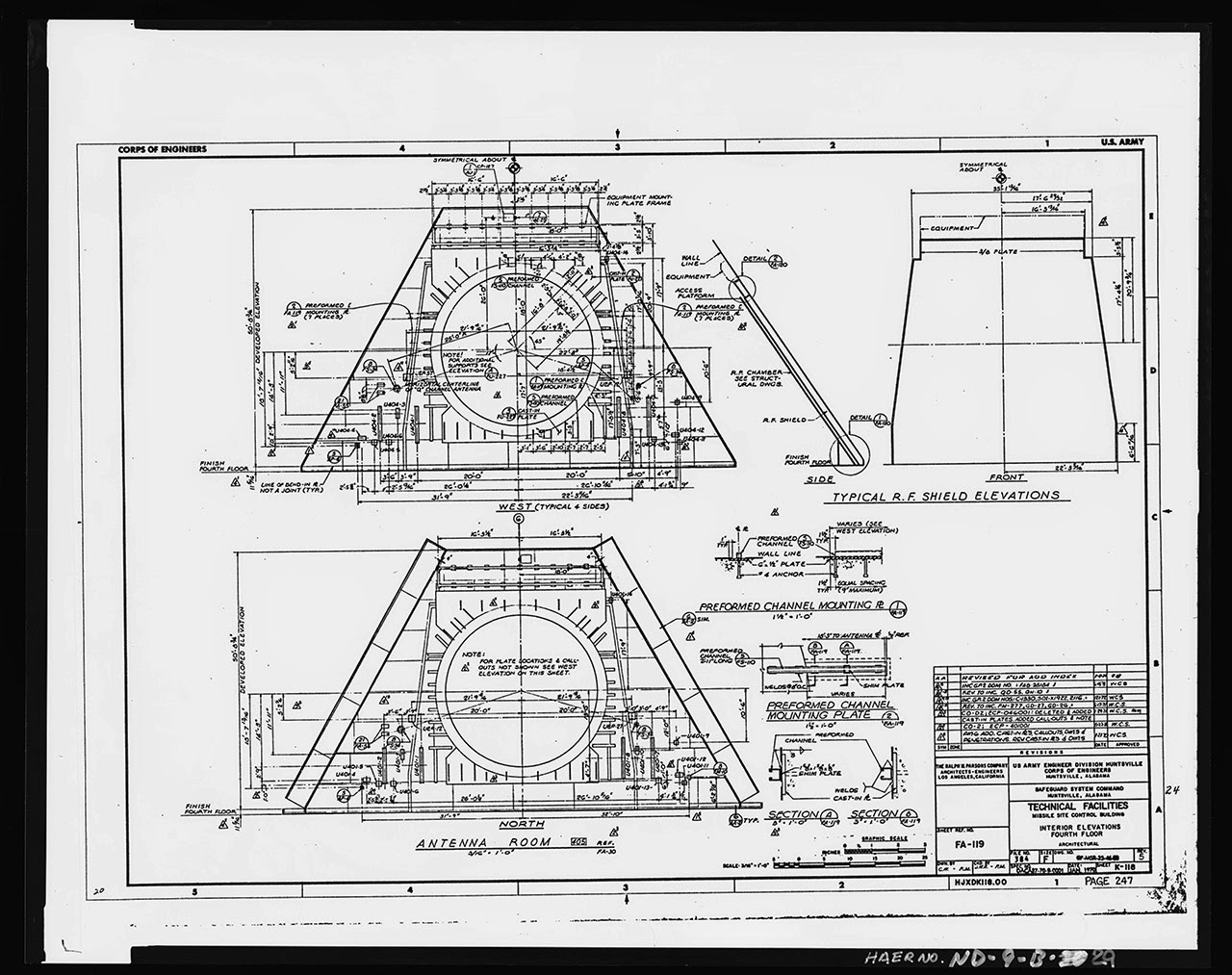

[Image: Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Image: Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the  [Image: Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Image: Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the  [Image: The pyramid, seen somewhat jarringly in full color, via

[Image: The pyramid, seen somewhat jarringly in full color, via

[Images: (top) Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Images: (top) Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the  [Image: Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Image: Photo by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Images: Photos by Benjamin Halpern, courtesy of the

[Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of  [Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: Photo courtesy of

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of lift bags being used in underwater archaeology; via

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of lift bags being used in underwater archaeology; via

[Images: Covers from old copies of

[Images: Covers from old copies of

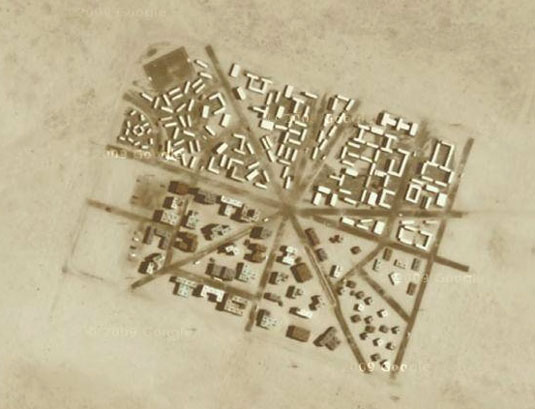

[Image: Yodaville, via

[Image: Yodaville, via  [Image: Photo by Richard Misrach, courtesy of the

[Image: Photo by Richard Misrach, courtesy of the

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: Photo by I. Yakovlev/Itar-Tass, courtesy of

[Image: Photo by I. Yakovlev/Itar-Tass, courtesy of

[Images: (top) photo by Tatjana Paunesku; (bottom) photo by S. Tapio. Courtesy of

[Images: (top) photo by Tatjana Paunesku; (bottom) photo by S. Tapio. Courtesy of

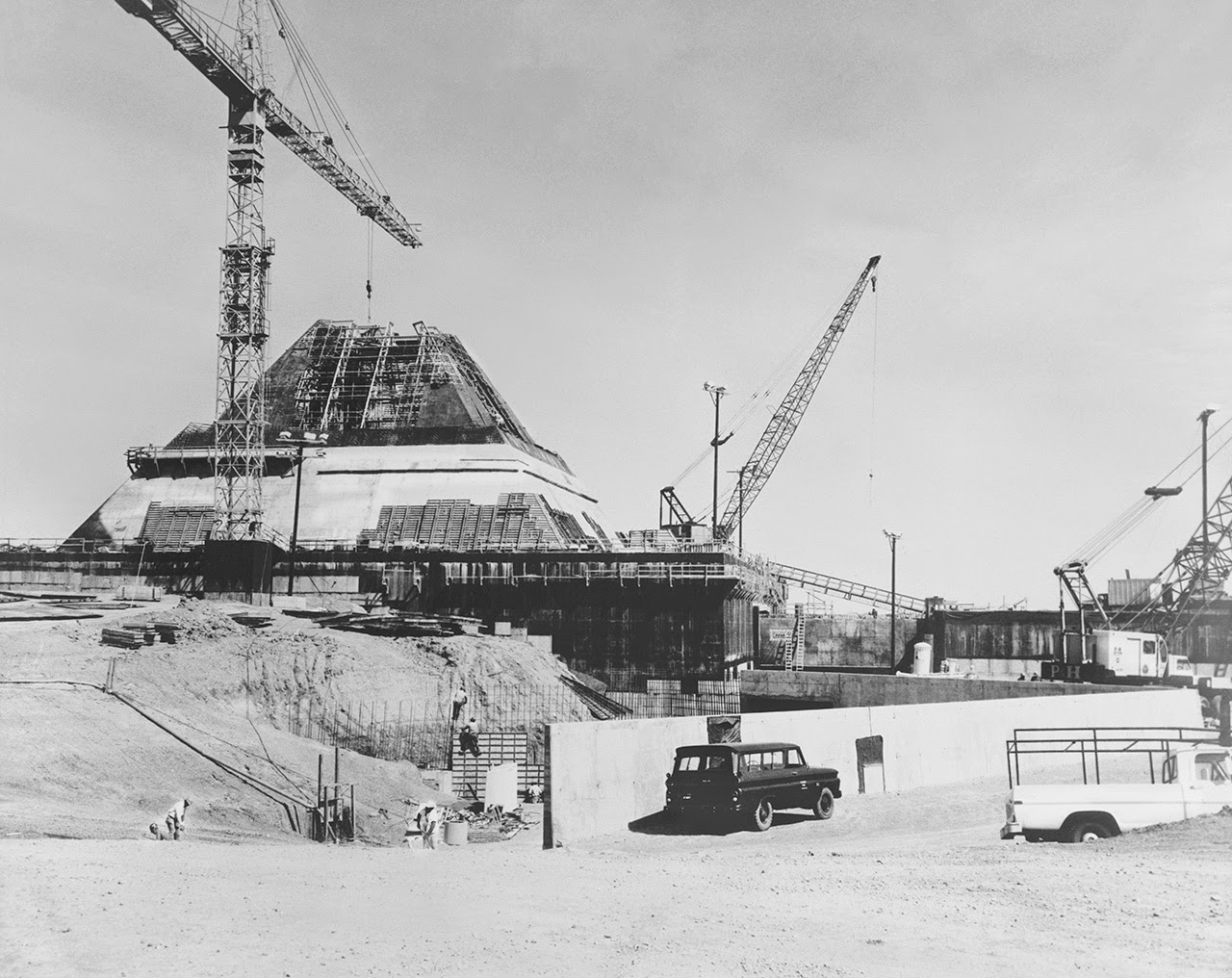

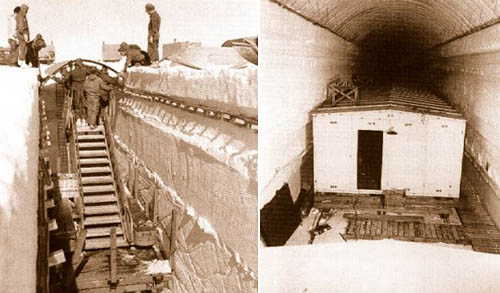

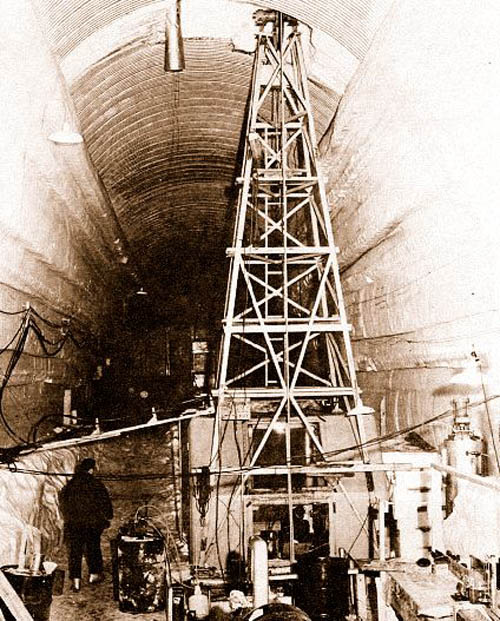

[Image: Camp Century under construction; photograph via

[Image: Camp Century under construction; photograph via

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via

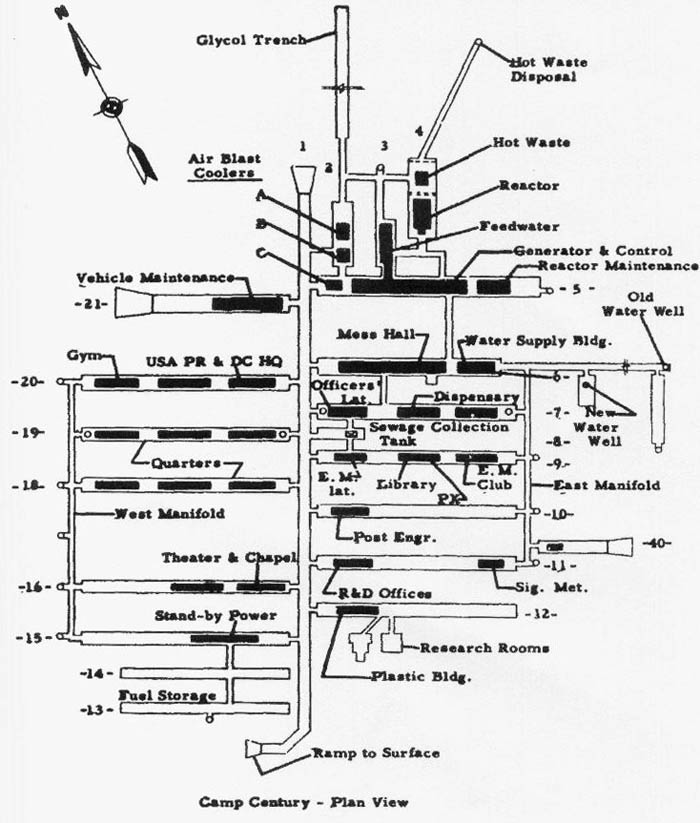

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via  [Image: The plan of Camp Century; via

[Image: The plan of Camp Century; via  [Image: U.S. Army photograph, via the

[Image: U.S. Army photograph, via the