[Image: Inside Tadao Ando’s studio in Osaka; photo by Kaita Takemura, via designboom].

[Image: Inside Tadao Ando’s studio in Osaka; photo by Kaita Takemura, via designboom].

Somewhere, despite the weather here, it’s spring. If you’re like me, that means you’re looking for something new to read. Here is a selection of books that have crossed my desk over the past few months—though, as always, I have not read every book listed here. I have, however, included only books that have caught my eye or seem particularly well-fit for BLDGBLOG readers due to their focus on questions of landscape, design, architecture, urbanism, and more.

For previous book round-ups, meanwhile, don’t miss the back-links at the bottom of this post.

1) The Strait Gate: Thresholds and Power in Western History by Daniel Jütte (Yale University Press)

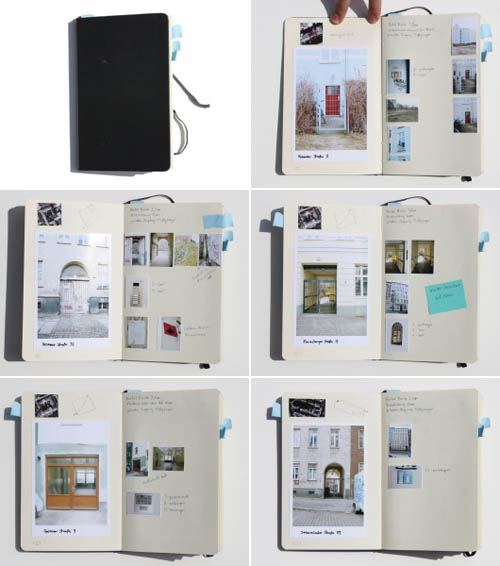

Daniel Jütte’s The Strait Gate seems largely to have slipped under the radar, but it’s my pick for the most interesting architectural book of the last year (it came out in 2015). It has a deceptively simple premise. In it, Jütte tells the story of the door in European history: the door’s ritual symbolism, its legal power, its artistic possibilities, even its betrayal through basic crimes such as trespassing and burglary. He calls it “a study of doors, gates, and keys and a history of the hopes and anxieties that Western culture has attached to them”; it is a way of “looking at history through doors.”

Jütte describes locks (and their absence), city walls (and their destruction), marriage (and the literal threshold a newly joined couple must cross), medicinal rituals (connected “with the idea of passing through a doorway”), even the doorway to Hell (and its miraculous sundering). You know you’re reading a good book, I’d suggest, when something pops up on nearly every page that you need to mark with a note for coming back to later or that gives you some unexpected new historical or conceptual detail you want to write about more yourself. An entire seminar could be based on this one book alone.

2) Witches of America by Alex Mar (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

Witches of America is simultaneously an introduction to alternative religious practices in the United States—specifically, contemporary paganism, broadly understood—and a first-person immersion in those movements and their cultures. As such, the book is a personal narrative of attraction to—but also ongoing frustration with—the world found outside mainstream beliefs or creeds.

As such, it ostensibly falls beyond the pale of BLDGBLOG, yet the book is worth including here for what it reveals about the spatial settings of these new and, for me, surprisingly vibrant communities. There is the abandoned churchyard in New Orleans, for example, now repurposed—and redecorated—by a group of 21st-century acolytes of Aleister Crowley; there is the remote stone circle built in Northern California by what I would describe as a post-hippie couple with access to land-moving equipment; there is the otherwise indistinguishable collegiate house in central Massachusetts where future “priests” train in the shadow of New England’s peculiar history with witch trials; there is the corporate convention center in downtown San Jose; the overgrown tombs of the Mississippi Delta, where we meet a rather extraordinary—and macabre—burglar; there is even what sounds like an Airbnb rental gone unusually haywire in the hills of New Hampshire.

While descriptions of these settings are certainly not the subject of Alex Mar’s book, it is nonetheless fascinating to see the world of the esoteric, the otherworldly, or, yes, the occult presented in the context of our own everyday surroundings, with all of their often-mundane dimensions and atmosphere. This alone should make this an interesting read, even for those who might not share the author’s curiosity about the “witches of America.”

3) The Work of the Dead: A Cultural History of Mortal Remains by Thomas W. Laqueur (Princeton University Press)

The Work of the Dead looks at the role not just of death but specifically of dead bodies in shaping our cities, our landscapes, our battlefields, and our imaginations. The question of what to do with the human corpse—how to venerate it, but also how to do dispose of it and how to protect ourselves from its perceived pestilence—has led, and continues to lead, to any number of spatial solutions.

Laqueur writes that “there seems to be a universally shared feeling not only that there is something deeply wrong about not caring for the dead body in some fashion, but also that the uncared-for body, no matter the cultural norms, is unbearable. The corpse demands the attention of the living.”

Graveyards, catacombs, monuments, charnel grounds: these are landscapes designed in response to human mortality, reflective of a culture’s attitude to personal disappearance and emotional loss. While author Thomas Laqueur’s approach is often dry (and long-winded), the book’s thorough framing of its subject lends it an appropriate weight for something as universal as the end of life.

If this topic interests you, meanwhile, I also recommend Necropolis: London and Its Dead by Catharine Arnold (Simon & Schuster), as well as Making an Exit: From the Magnificent to the Macabre—How We Dignify the Dead by Sarah Murray (Picador).

4) The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s New World by Andrea Wulf (Alfred A. Knopf)

Andrea Wulf’s biography of Alexander von Humboldt has justifiably won the author a series of literary awards. Its subject matter is by no means light, yet the book has the feel of an adventure tale, pulling double duty as the life-story of a European scientist and explorer but also as a history of scientific ideas, ranging from the origins of color and the nature of speciation to some of the earliest indications of global atmospheric shifts—that is, of the possibility of climate change.

Natural selection, cosmology, volcanoes—even huge South American lakes full of electric eels—the book is a great reminder of the importance of curiosity and travel, not to mention the value of an inhuman world against which we should regularly measure ourselves (and come out lacking). “In a world where we tend to draw a sharp line between the sciences and the arts, between the subjective and the objective,” Wulf writes, “Humboldt’s insight that we can only truly understand nature by using our imagination makes him a visionary.”

5) Sounding the Limits of Life: Essays in the Anthropology of Biology and Beyond by Stefan Helmreich (Princeton University Press)

You might recall seeing Stefan Helmreich’s work described here before—specifically his earlier book, Alien Ocean: Anthropological Voyages in Microbial Seas—but Sounding the Limits of Life is arguably even more relevant to many of the ongoing themes explored here on the blog.

In his new book, Helmreich outlines a kind of acoustic ecology of the oceans, placing deep-sea creatures and shallow reefs alike in a world of immersive sound and ambient noise, now all too often interrupted by the deafening pings of naval sonar. He also uses the seemingly alien environment of the seas, however, to expand the conversation to include speculation about what life might be like elsewhere, using maritime biology as a launching point for discussing SETI, artificial digital lifeforms, Martian fossils (from Martian seas), and much more.

It’s a book about how our “definition of ‘life’ is becoming unfastened from its familiar grounding in earthly organisms,” Helmreich writes, as well as an attempt to explore “what life is, has been, and may yet become—whether that life is simulated, microbial, extraterrestrial, cetacean, anthozoan, planetary, submarine, oceanic, auditory, or otherwise.”

6) Pinpoint: How GPS Is Changing Technology, Culture, and Our Minds by Greg Milner (W.W. Norton)

I had been looking forward to this book, exploring the relationship between mapping and the world, ever since reading an op-ed by the author, Greg Milner, in The New York Times about “death by GPS.” Milner’s book is specifically about the Global Positioning System and its power over our lives: how GPS shapes our sense of direction and geography, what it has done for navigation on a planetary scale, and even how it has transformed the way we grow our global food supply.

7) The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty by Benjamin Bratton (MIT Press)

Design theorist Benjamin Bratton’s magnum opus is a fever-dream of computational geopolitics, “accidental megastructures,” cloud warfare, predictive mass surveillance, speculative anthropology, digital futurism, infrastructural conspiracy theory—a complete list would be as long as Bratton’s already substantial book, and would also overlap quite well with the utopian/dystopian science fiction it often seems inspired by.

In Bratton’s hands, these abstract topics become, at times, almost incantatory—as if William S. Burroughs had taken a day job with the RAND Corporation. As information technology continues to exhibit geopolitical effects, Bratton writes, “borderlines are rewritten, dashed, curved, erased, automated; algorithms count as continental divides; (…) interfaces upon interfaces accumulate into networks, which accumulate into territories, which accumulate into geoscapes (…); the flat, looping planes of jurisdiction multiply and overlap into towered, interwoven stacks…” He writes of “supercomputational utopias” and the “ambient geopolitics of consumable electrons.”

It’s a mind-bending and utterly unique take on technology’s intersection with—and forced mutation of—governance.

8) You Belong To The Universe: Buckminster Fuller and the Future by Jonathon Keats (Oxford University Press)

Jonathon Keats’s new book simultaneously attempts to debunk and to clarify some of the cultural myths surrounding Buckminster Fuller, a man who described himself, Keats reminds us, as a “comprehensive anticipatory design scientist.” For fans of Fuller’s work, you’ll find the usual suspects here—his jewel-like geodesic domes, his prescient-if-ungainly Dymaxion homes—but also a chapter about Fuller’s work with and influence on the U.S. military in an age of nuclear war games and “domino theories” overshadowing Vietnam.

9) Rome Measured and Imagined: Early Modern Maps of the Eternal City by Jessica Maier (University of Chicago Press)

Art historian Jessica Maier’s book suggests that changes in the way the city of Rome was mapped over the centuries simultaneously reveal larger shifts in European cultural understandings of space and geography. Her argument hinges on a sequence of surveys and maps chosen not just for their visual or cartographic power—which is considerable, as the book has many gorgeous reproductions of old engraved city maps, views, and diagrams—but for their influence on later geographic projects to come.

Broadly speaking, the documents Maier discusses are meant to be seen as passing from being artistic, narrative, or abstractly emblematic of the idea of greater “Rome” to a more rigorous, modern approach based in measurement, not mythology.

This widely accepted historical narrative begins to crumble, however, as Maier puts pressure on it, especially through the example of Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s etching of the Campus Martius. This is an image of Rome that “was neither documentary nor reconstructive,” Maier suggests, and that thus had more in common with those earlier, more folkloristic emblems of the city. In today’s vocabulary, we might even describe Piranesi’s Campus Martius as an example of “design fiction.”

10) Till We Have Built Jerusalem: Architects of the New City by Adina Hoffman (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

This is a remarkable and often beautifully written history of modern Jerusalem, as told from the point of view of its architecture. Jerusalem is a city, author Adina Hoffman writes, that “has a funny way of burying much of what it builds.” It is a place of “burials, erasures, and attempts to mark political turf by means of culturally symbolic architecture and hastily rewritten maps.” The book, she adds, “is an excavation in search of the traces of three Jerusalems and the singular builders who envisioned them.”

Indeed, the book is structured around the lives of three architects. The story of German Jewish designer Erich Mendelsohn—probably most well-known today for his futurist “Einstein Tower” in Potsdam—looms large, as do the lives of Austen St. Barbe Harrison, “Palestine’s chief government architect,” and the “possibly Greek, possibly Arab” Spyro Houris.

Hoffman’s work is a mix of the archaeological, the biographical, and even the geopolitical, as individual building sites—even specific businesses and kilns—become microcosms of territorial significance, embedded in and misused by nationalistic narratives that continue to reach far beyond the boundaries of the city.

11) City of Demons: Violence, Ritual, and Christian Power in Late Antiquity by Dayna S. Kalleres (University of California Press)

City of Demons looks at three cities—Antioch, Jerusalem, and Milan—in the context of early Christianity, when the streets and back alleys of each metropolis were still lined with temples dedicated to older gods and when alleged opportunities for spiritual corruption seemed to lie around every corner. Historian Dayna Kalleres writes that the cities of late antiquity were all but contaminated with demons: imagined malignant forces that had to be repelled by Christian ritual and belief. Cities, in other words, had to be literally exorcized by a practice of “urban demonology,” driven out of the metropolis by such things as church-building schemes and public processions.

While the book is, of course, an academic history, it is also evocative of something much more literary and thrilling, which is a nearly-forgotten phase of Western urban history when forces of black magic lurked in nearly every doorway and civilians faced security threats not from terrorists but from “the marginal, ambiguous, and protean,” from these hidden demonological influences that the righteous were compelled to expunge.

12) City of Thorns: Nine Lives in the World’s Largest Refugee Camp by Ben Rawlence (Picador)

City of Thorns looks at the Dadaab refugee camp in northern Kenya through various lenses: economic, political, and humanitarian, to be sure, but also ethical and anthropological, even to a certain extent architectural.

While author Ben Rawlence’s goal is not, thankfully, to discuss the camp in terms of its design, he does nevertheless offer a crisp descriptive introduction to life in a sprawling settlement such as this, from its cinemas and police patrols to its health facilities and homes. “Our myths and religions are steeped in the lore of exile,” he writes, “and yet we fail to treat the living examples of that condition as fully human.” The camp, we might say in this context, is the urbanism of exile.

13) Ghettoside: A True Story of Murder in America by Jill Leovy (Spiegel & Grau)

I went through a nearly three-year spate of reading law-enforcement memoirs and books about urban policing while researching my own book, A Burglar’s Guide to the City. The excellent Ghettoside by Jill Leovy came out at the very end of that peculiar literary diet—but it also showed up the rest of those books quite handily.

Ghettoside is bracing, sympathetic, and emotionally nuanced in its week-by-week portrayal of LAPD homicide detectives investigating the murder of a fellow detective’s teenage son. Much larger than this, however, is Leovy’s dedication throughout the book to sorting through the overlapping mazes of media disinformation that have turned “black-on-black” crime into nothing more than a dismissive explanation of something genuinely horrific, a way to paper-over “racist interpretations of homicide statistics,” in reviewer Hari Kunzru’s words. More damningly, Ghettoside insists, this ongoing wave of murders and revenge-killings is not some new urban state of nature, but is entirely capable of being stopped.

Indeed, Leovy clearly and soberly shows through years of L.A. homicide reporting that today’s epidemic of violence primarily targeting African-American males is due to a failure of law enforcement—or, in her words, “where the criminal justice system fails to respond vigorously to violent injury and death, homicide becomes endemic.” Yet the answer, she explains, is more policing, not less. As an endorsement of effective, community-centered police work, the book is unparalleled.

No matter what side you think you might be on in the growing—and entirely unnecessary—divide between police and the populace they are hired to serve, this is a superb guide to the complexities of law enforcement in contemporary Los Angeles and, by extension, in every American metropolis.

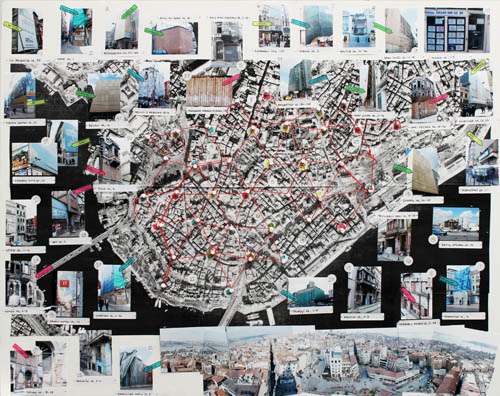

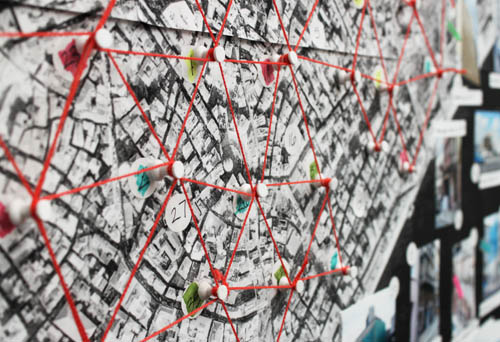

14) The City That Never Was by Christopher Marcinkoski (Princeton Architectural Press)

Christopher Marcinkoski’s book is a fascinating exploration of the relationships between “volatile fiscal events” and “speculative urbanization,” with a specific focus on a cluster of failed urban projects in Spain. Marcincoski defines speculative urbanization as “the construction of new urban infrastructure or settlement for primarily political or economic purposes, rather than to meet real (as opposed to artificially projected) demographic or market demand.”

Although the author jokes that his book is actually quite late to the conversation—discussing the spatial fallout of a global financial crisis that was already five years old by the time he began writing—it is actually a remarkably timely study, as well as a sad assessment of how easily architectural production can become ensnared in economic forces far more powerful than humanism or design.

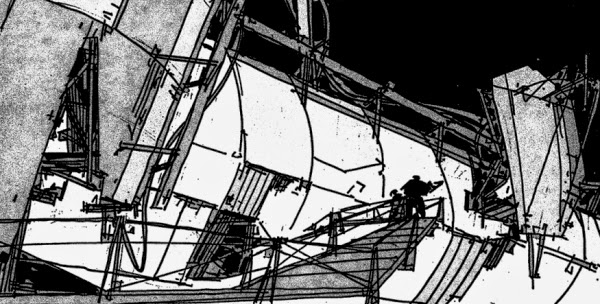

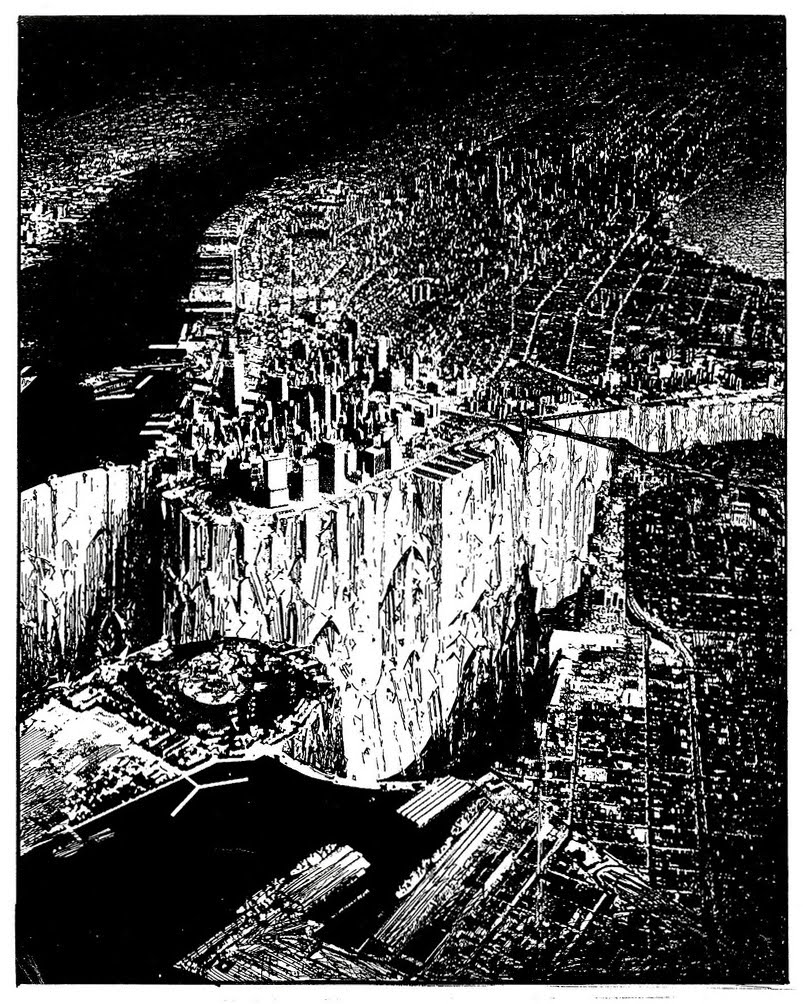

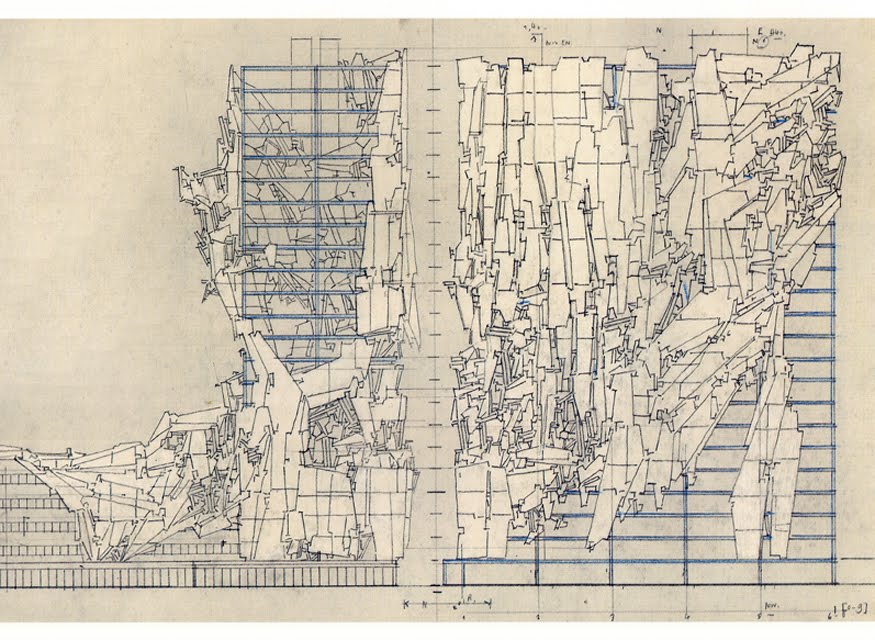

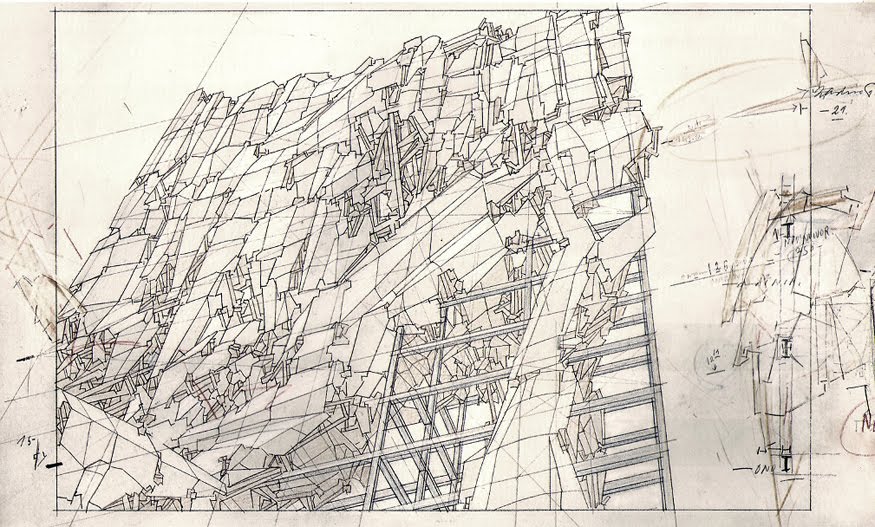

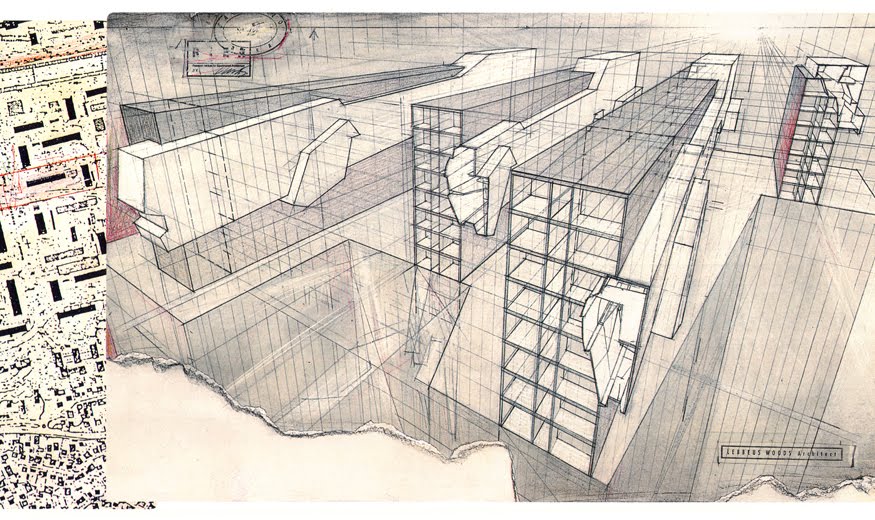

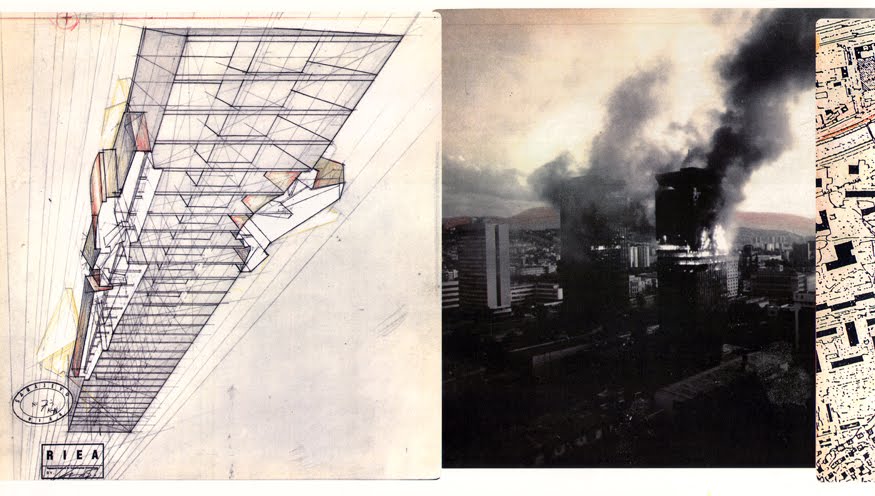

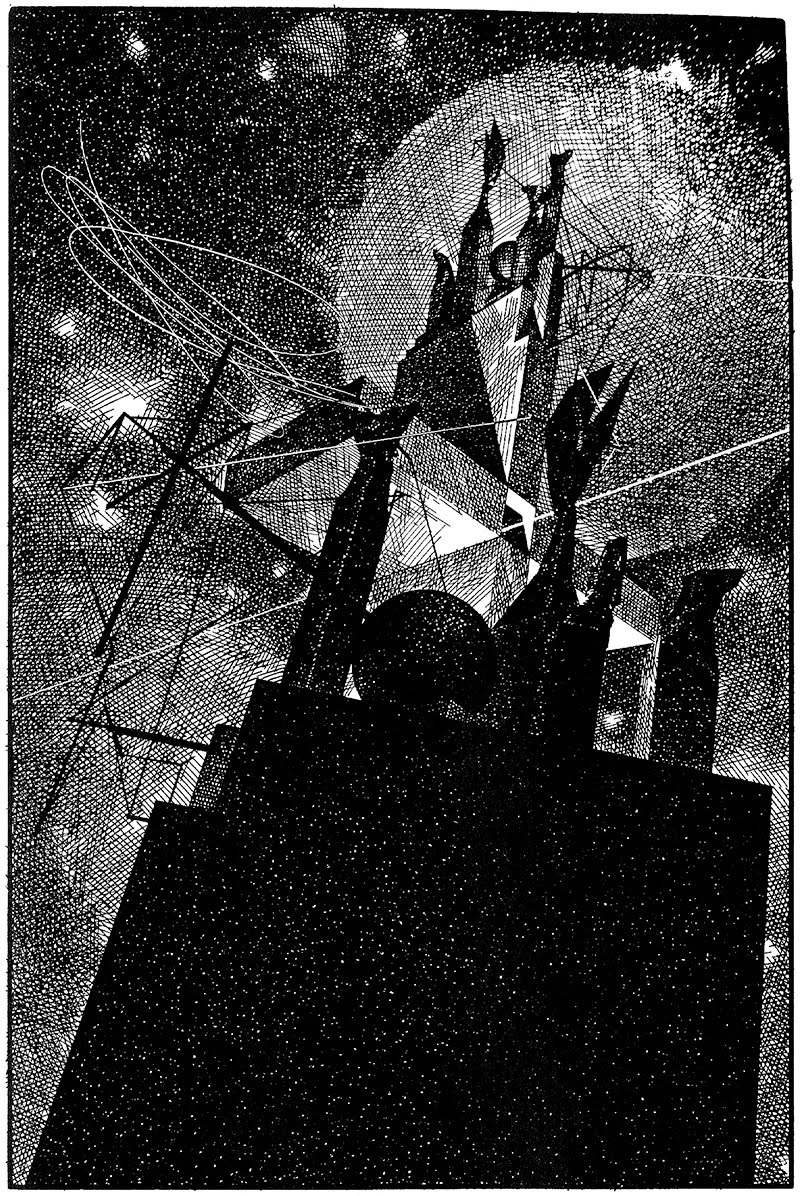

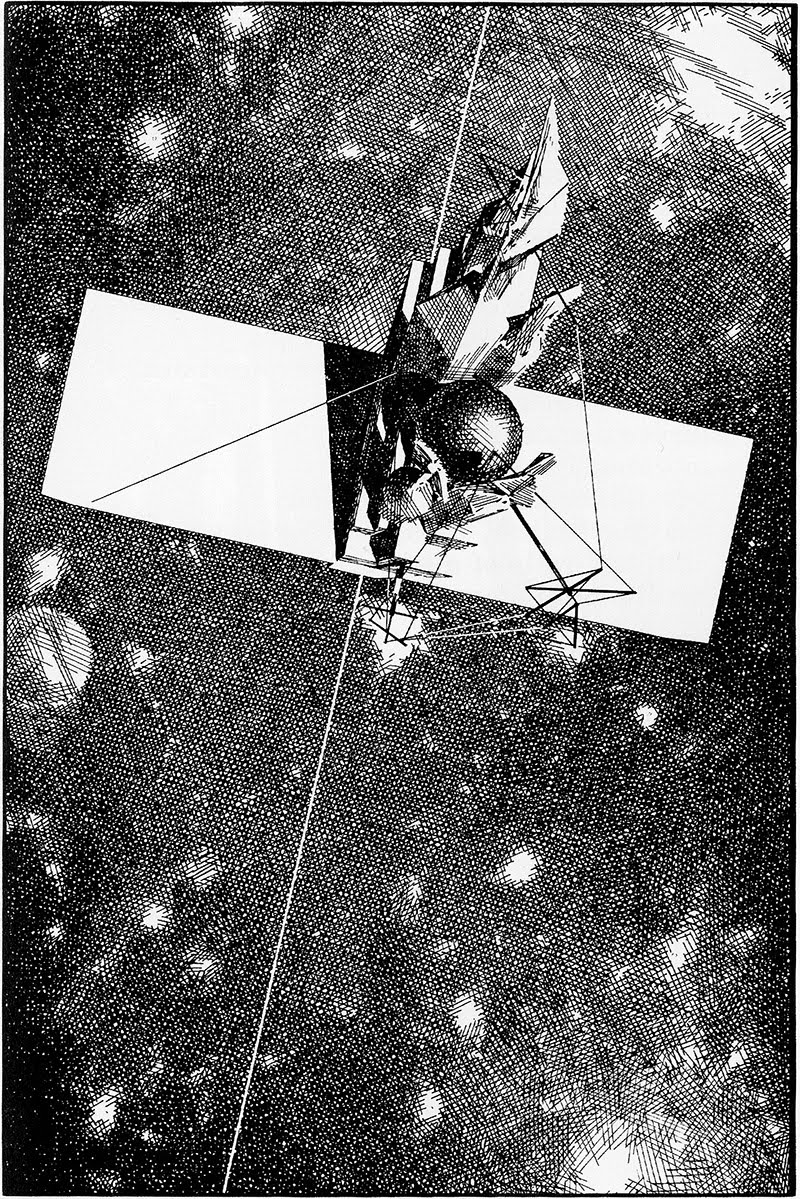

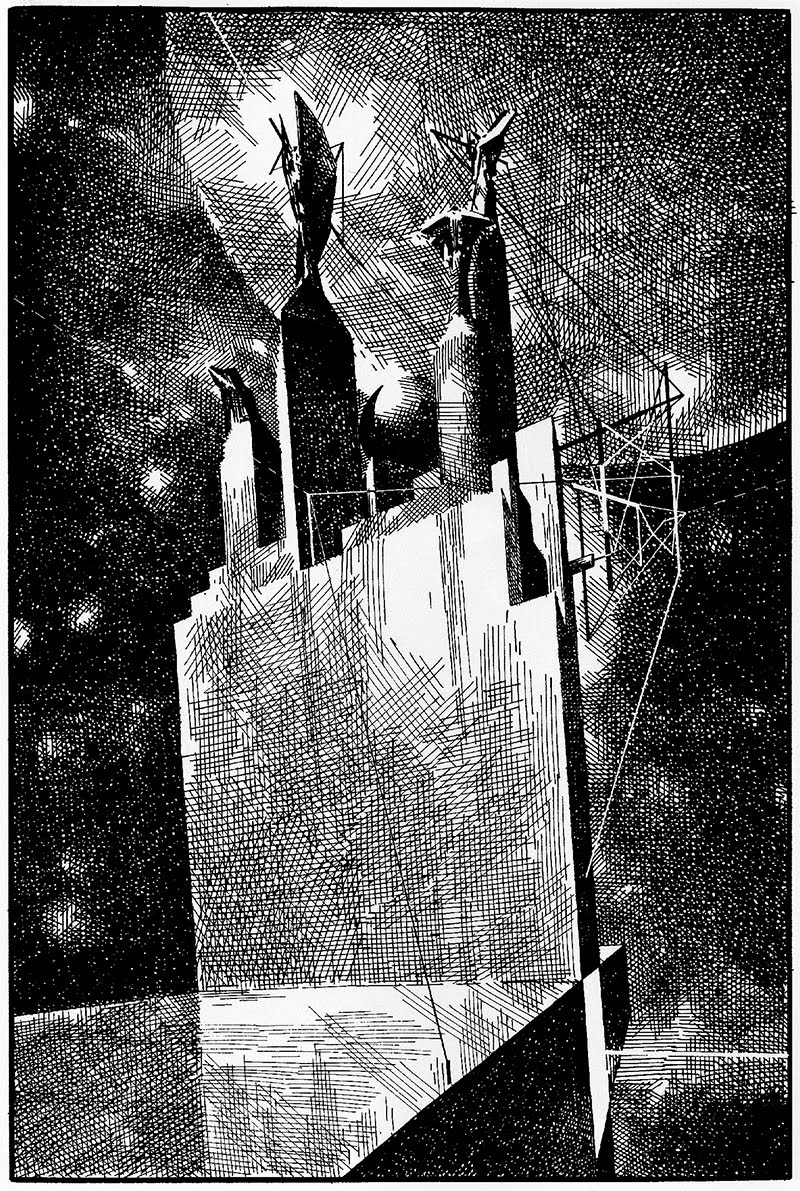

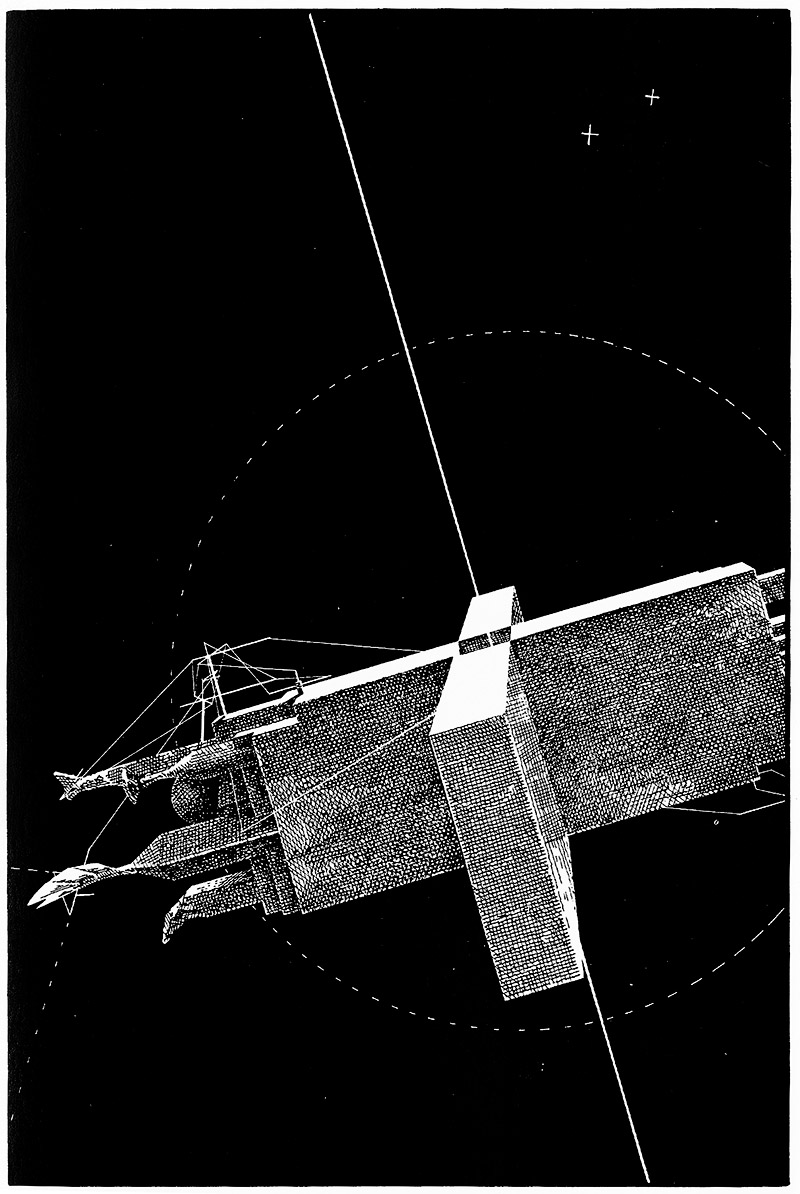

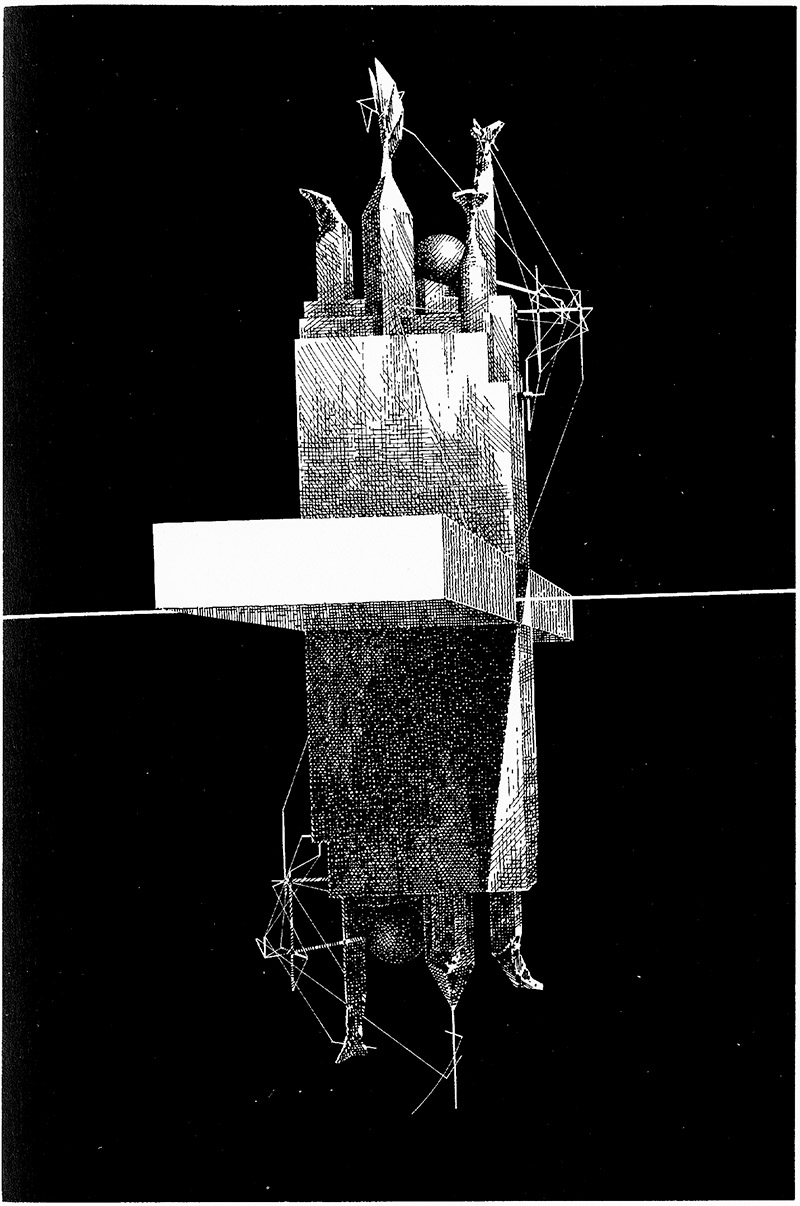

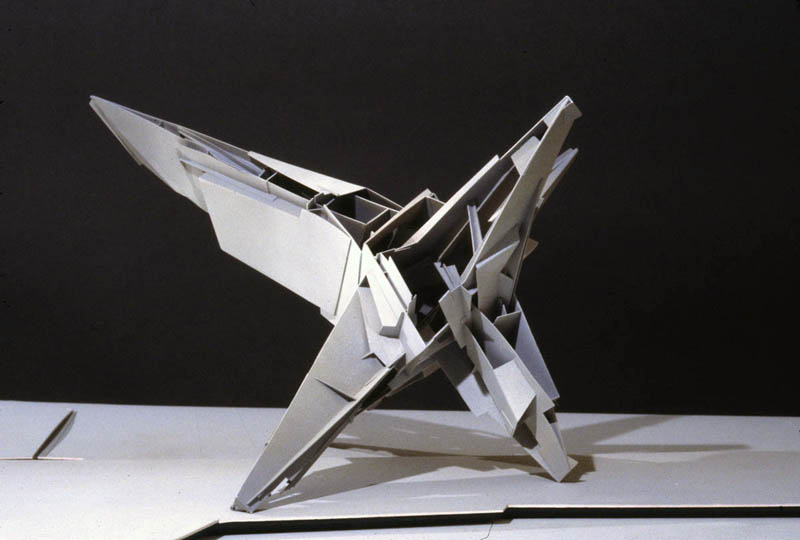

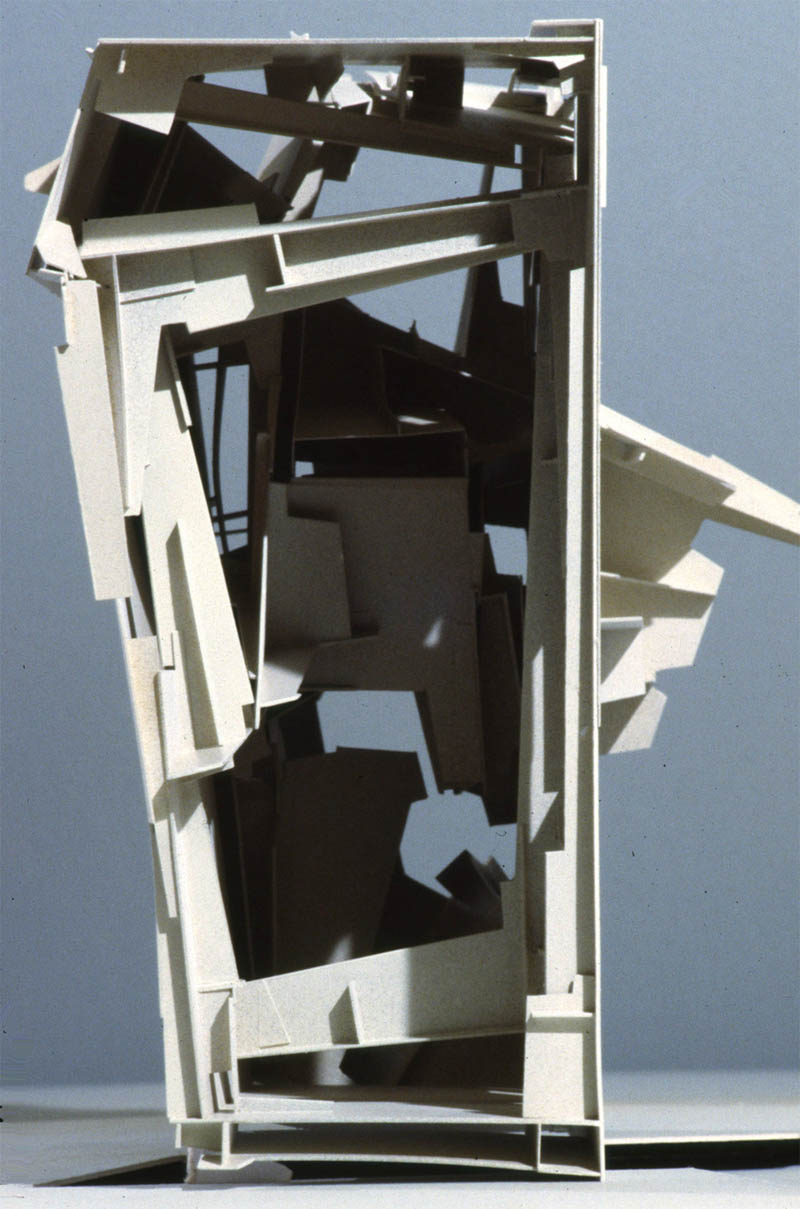

15) Slow Manifesto: Lebbeus Woods Blog edited by Clare Jacobson (Princeton Architectural Press)

Lebbeus Woods was both a friend and a personal hero of mine; his blog, which lasted from 2007 to shortly before his death in 2012, has now been collated, edited, and preserved by Princeton Architectural Press, with more than 300 individual entries. While primarily text, the books also includes several black-and-white images, including pages from his otherworldly sketchbooks. Thoughts on “wild buildings,” war, borders, September 11th, the now also deceased designer Zaha Hadid, and Woods’s own intriguing mix of cinematic/fictional and analytic/documentary modes of writing abound.

16) Almost Nature by Gerco de Ruijter (Timmer Art Books)

I’ve written about Dutch photographer Gerco de Ruijter fairly extensively in the past—most recently in a piece about “grid corrections”—so I was thrilled to see that some of his aerial work has been collected in a new, beautifully realized edition. It collects photos of stabilized coastlines and tree farms, grids and borders.

“Is the wilderness wild?” an accompanying text by Dirk van Weelden asks. “Cities and industrial farming make it seem man is in perfect control,” van Weelden continues later in the essay. “The reality is far more interesting. (…) The truly uncontrollable forces of nature are mutation, chance, hybridity, and contamination,” all subjects de Ruijter’s photos document at various scales, in every season.

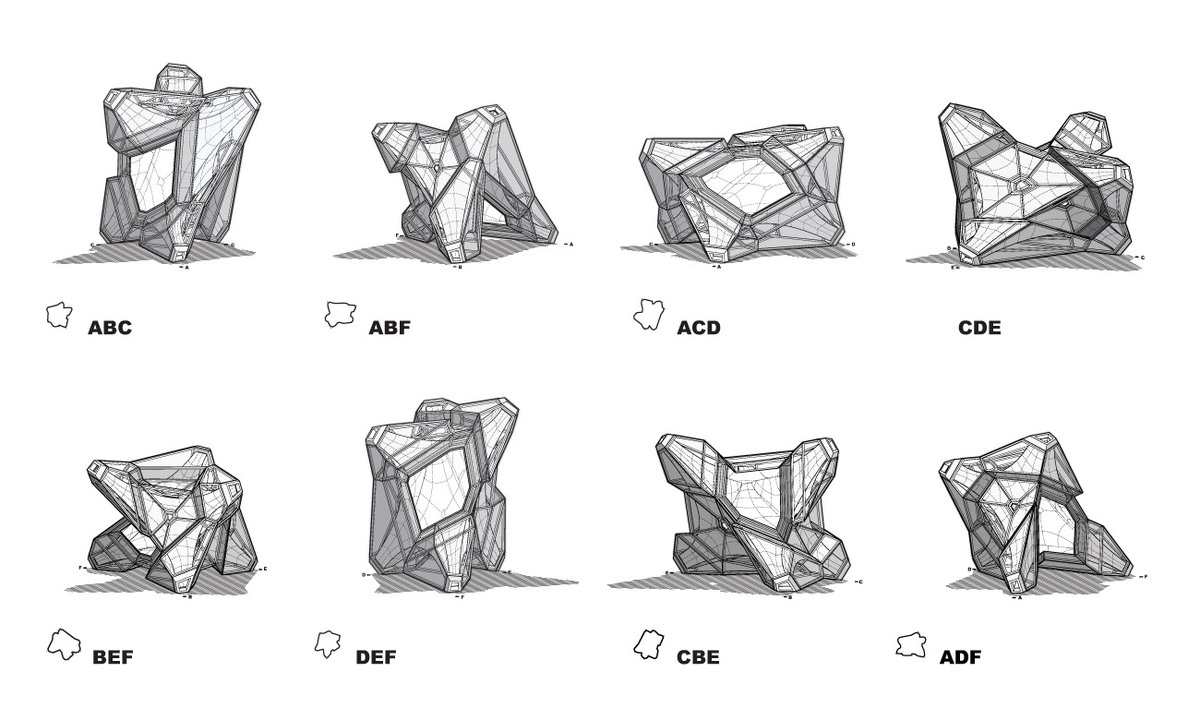

17) Niche Tactics: Generative Relationships Between Architecture and Site by Caroline O’Donnell (Routledge)

In the guise of what looks—and even, to some extent, physically feels—like a textbook there is hidden a fantastic study of how buildings relate to their surroundings.

More precisely, Caroline O’Donnell’s investigation of “architecture and site” hopes to reveal how, during the design process, the context of a building affects that building’s final form. Questions of autonomy (do buildings need to reflect or refer to their settings at all?) and generation (can the essence of a site be “extracted” to give shape to the final building?) are woven through a series of essays about ugliness, architectural history, colonialism, monstrosity, and more.

18) How to Thrive in the Next Economy: Designing Tomorrow’s World Today by John Thackara (Thames & Hudson)

John Thackara is already widely known for his advocacy of “sustainability” in design—a word I deliberately put in scare-quotes because Thackara himself would prefer, I presume, a term more like transformative or even revolutionary design. That is, design that can flip the world on its head, not through violence, but through unexpected and strategic solutions to problems that often remain undiagnosed or overlooked. This new, short book looks at everything from mass transit to internet access, clothing manufacture to desertification, aging to fresh water, seeking nothing less than “a new concept of the world.” “The core value of this emerging economy is stewardship,” he writes, “rather than extraction.”

19) Design and Violence edited by Paola Antonelli and Jamer Hunt (Museum of Modern Art)

This book, crisply designed by Shaz Madani, documents an exhibition and debate series of the same name hosted by the Museum of Modern Art. Presented here as a combination of short essays by various authors—myself included—and provocative design objects, products, and public events, the aim is both to startle and to moderate. That is, the book seeks to bring together conflicting sides of often quite fierce arguments about the role of design, including how design can be used to mitigate or even, on occasion, to perpetuate violence. There are 3D-printed guns and a short history of the AK-47 alongside examples of prison architecture, classified surveillance aircraft, slaughterhouse diagrams, and border walls, to name but a few.

• • •

Briefly noted. Other books that have crossed my desk this season include Pandemic: Tracking Contagions, from Cholera to Ebola and Beyond by Sonia Shah (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), Pirates, Prisoners, and Lepers: Lessons from Life Outside the Law by Paul H. Robinson and Sarah M. Robinson (Potomac Books), Memories of the Moon Age by Lukas Feireiss (Spector Books), Shanshui City by Ma Yansong (Lars Müller Publishers), the double publication of Scaling Infrastructure and Infrastructural Monument from the MIT Center for Advanced Urbanism (Princeton Architectural Press), Living Complex: From Zombie City to the New Communal by Niklas Maak (Hirmer), and Smoke Gets in Your Eyes: And Other Lessons from the Crematory by Caitlin Doughty (W.W. Norton).

Finally, although I have mentioned it many times before, I do also have a new book of my own that just came out last week, called A Burglar’s Guide to the City; if you’d prefer to sample the goods before purchasing, however, you can check out an excerpt in The New York Times Magazine. But please consider supporting BLDGBLOG by ordering a copy—not least because then we can talk about burglary, architecture, and heists…

Thanks!

All Books Received: August 2015, September 2013, December 2012, June 2012, December 2010 (“Climate Futures List”), May 2010, May 2009, and March 2009.

[Image: Photo by Yulia Grigoryants, courtesy New York Times.]

[Image: Photo by Yulia Grigoryants, courtesy New York Times.] [Image: Via

[Image: Via

[Images: Via

[Images: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Michelangelo’s sketches for the fortification of Florence].

[Image: Michelangelo’s sketches for the fortification of Florence]. [Image: Michelangelo’s sketches for the fortification of Florence].

[Image: Michelangelo’s sketches for the fortification of Florence]. [Image: Michelangelo’s sketches for the fortification of Florence].

[Image: Michelangelo’s sketches for the fortification of Florence]. [Image: A sinkhole in

[Image: A sinkhole in  [Image: Infrastructure near Wink, Texas].

[Image: Infrastructure near Wink, Texas]. [Image: Inside Tadao Ando’s studio in Osaka; photo by Kaita Takemura, via

[Image: Inside Tadao Ando’s studio in Osaka; photo by Kaita Takemura, via

[Image: Screengrab from

[Image: Screengrab from  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: “Lower Manhattan” (1999) by Lebbeus Woods, discussed extensively

[Image: “Lower Manhattan” (1999) by Lebbeus Woods, discussed extensively

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: “Einstein Tomb” by Lebbeus Woods].

[Image: “Einstein Tomb” by Lebbeus Woods]. [Image: “Einstein Tomb” by Lebbeus Woods].

[Image: “Einstein Tomb” by Lebbeus Woods]. [Image: “Einstein Tomb” by Lebbeus Woods].

[Image: “Einstein Tomb” by Lebbeus Woods]. [Image: “Einstein Tomb” by Lebbeus Woods].

[Image: “Einstein Tomb” by Lebbeus Woods]. [Image: “Einstein Tomb” by Lebbeus Woods].

[Image: “Einstein Tomb” by Lebbeus Woods].

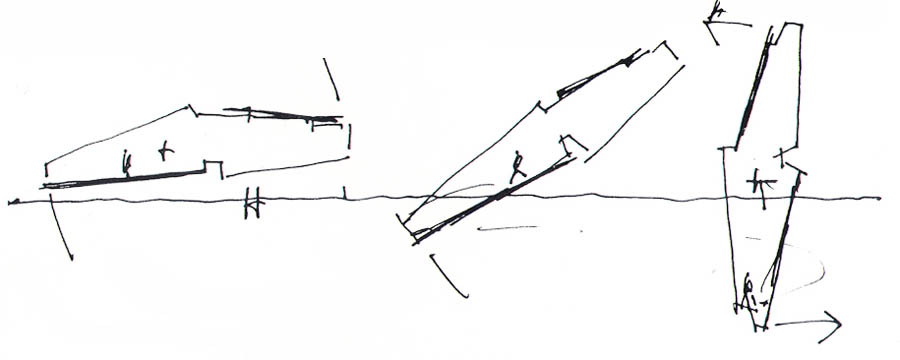

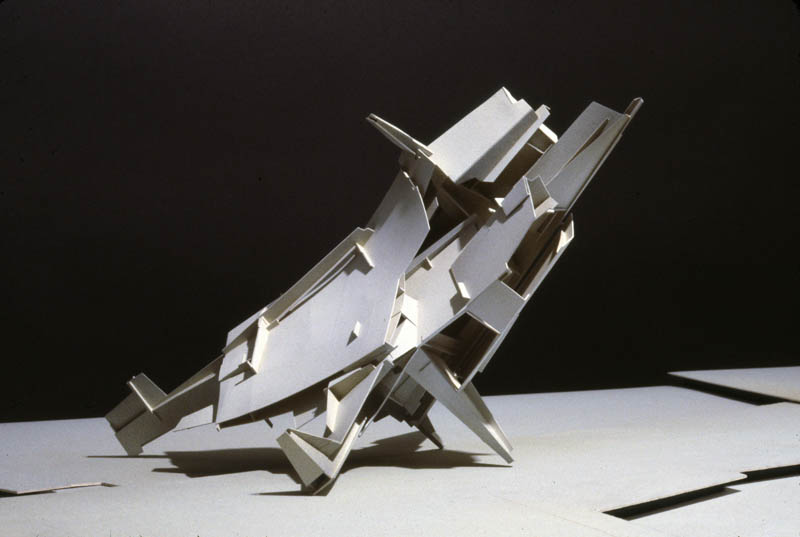

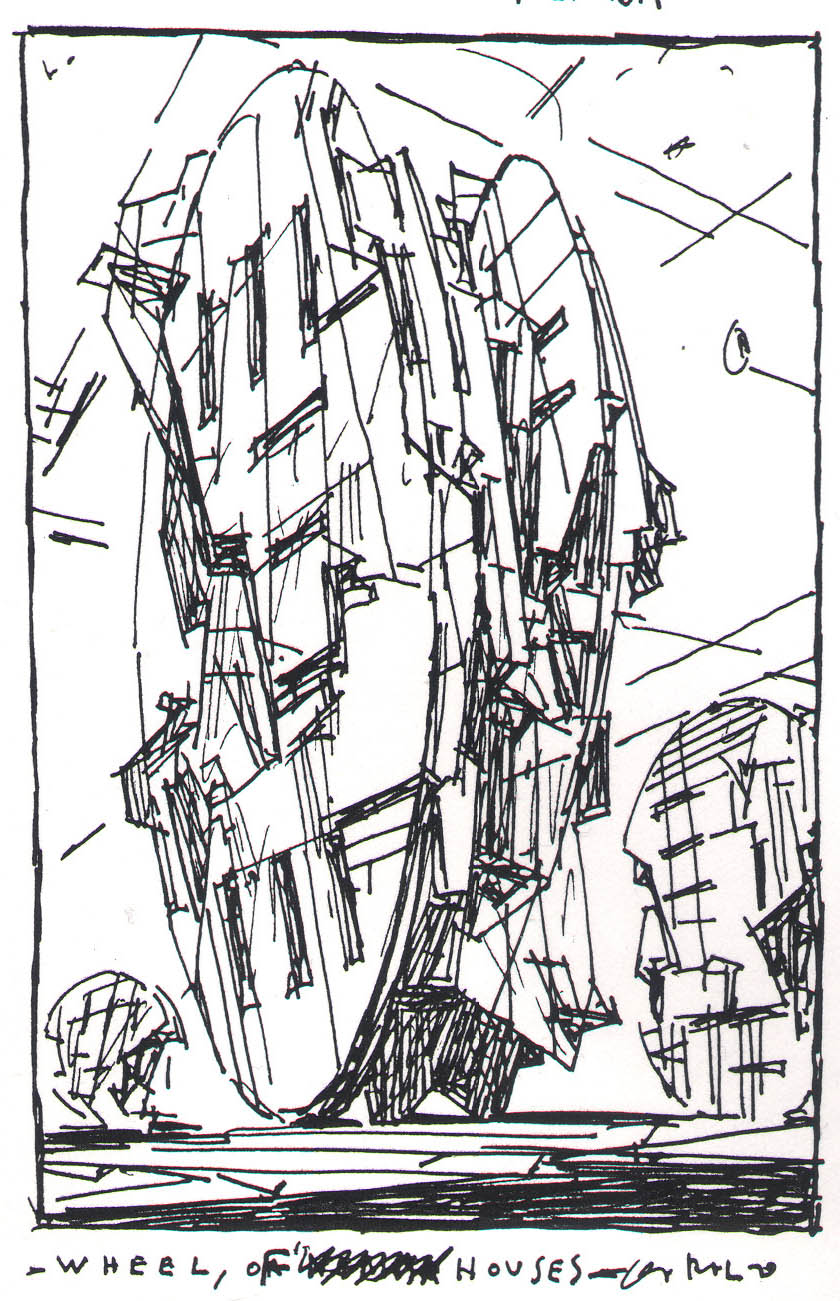

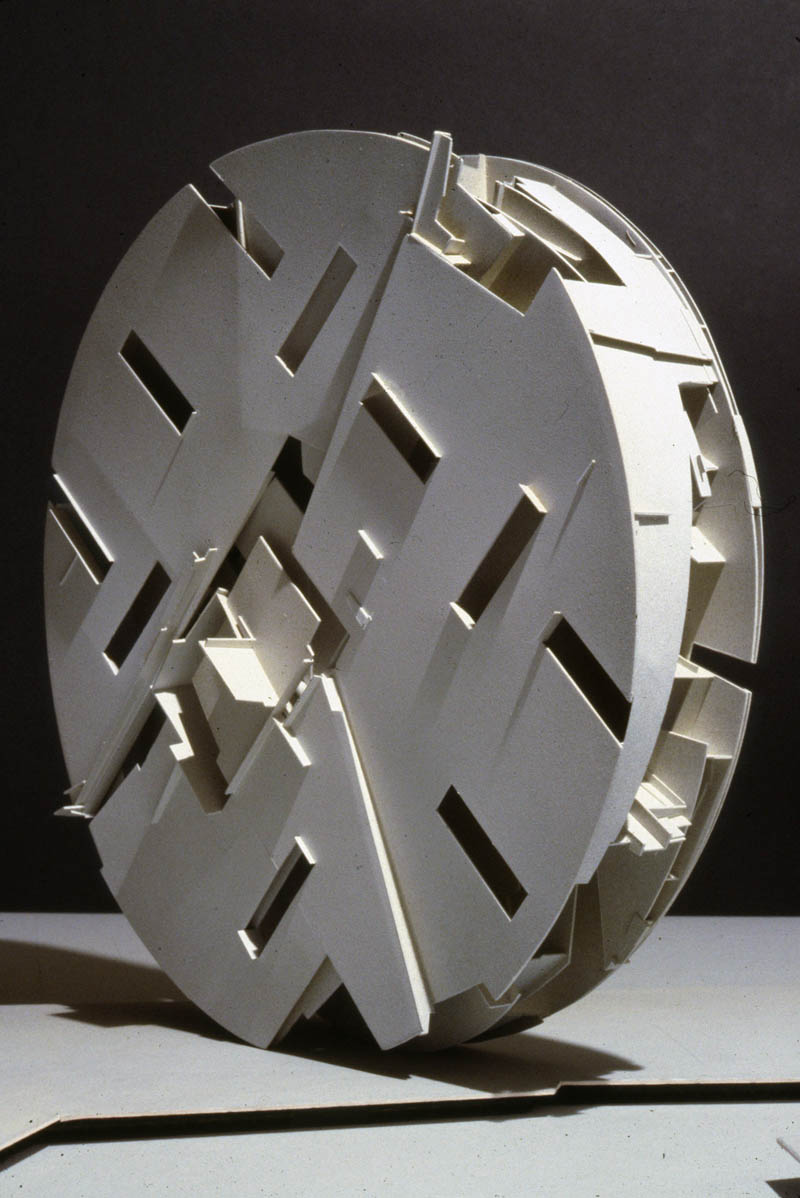

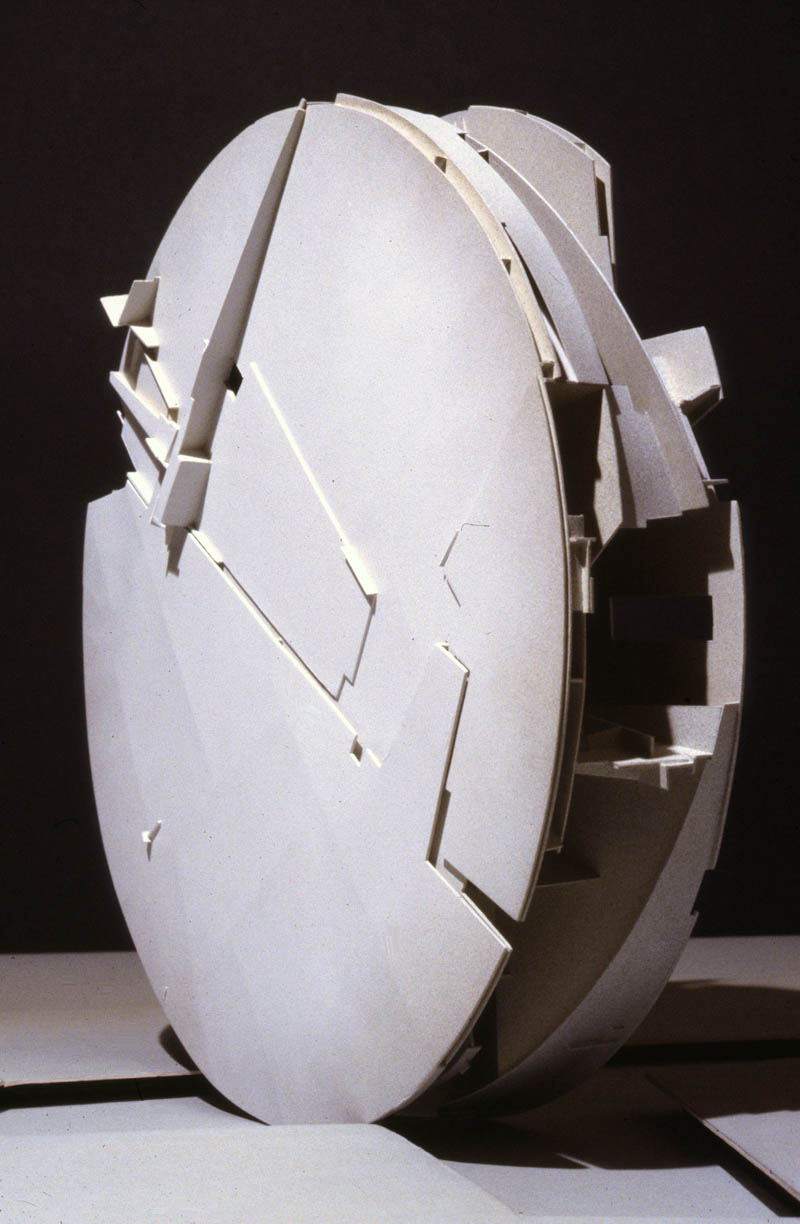

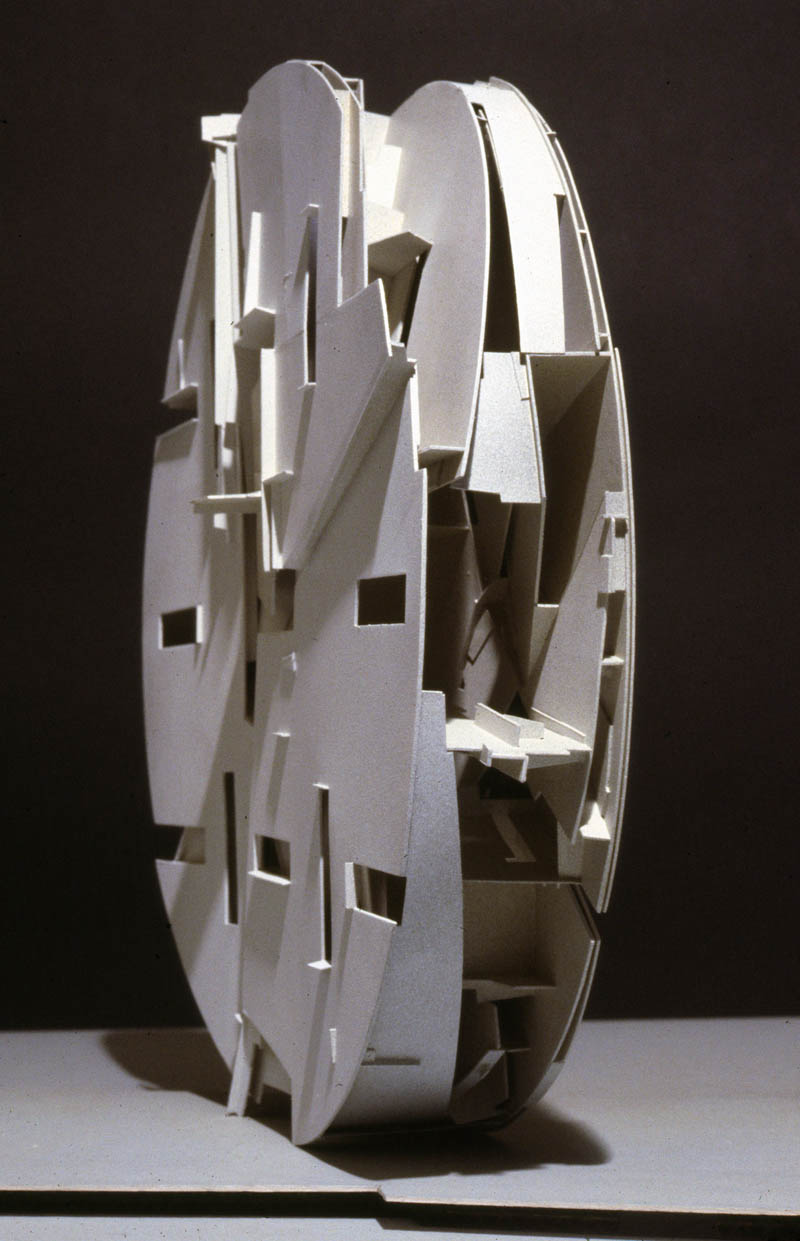

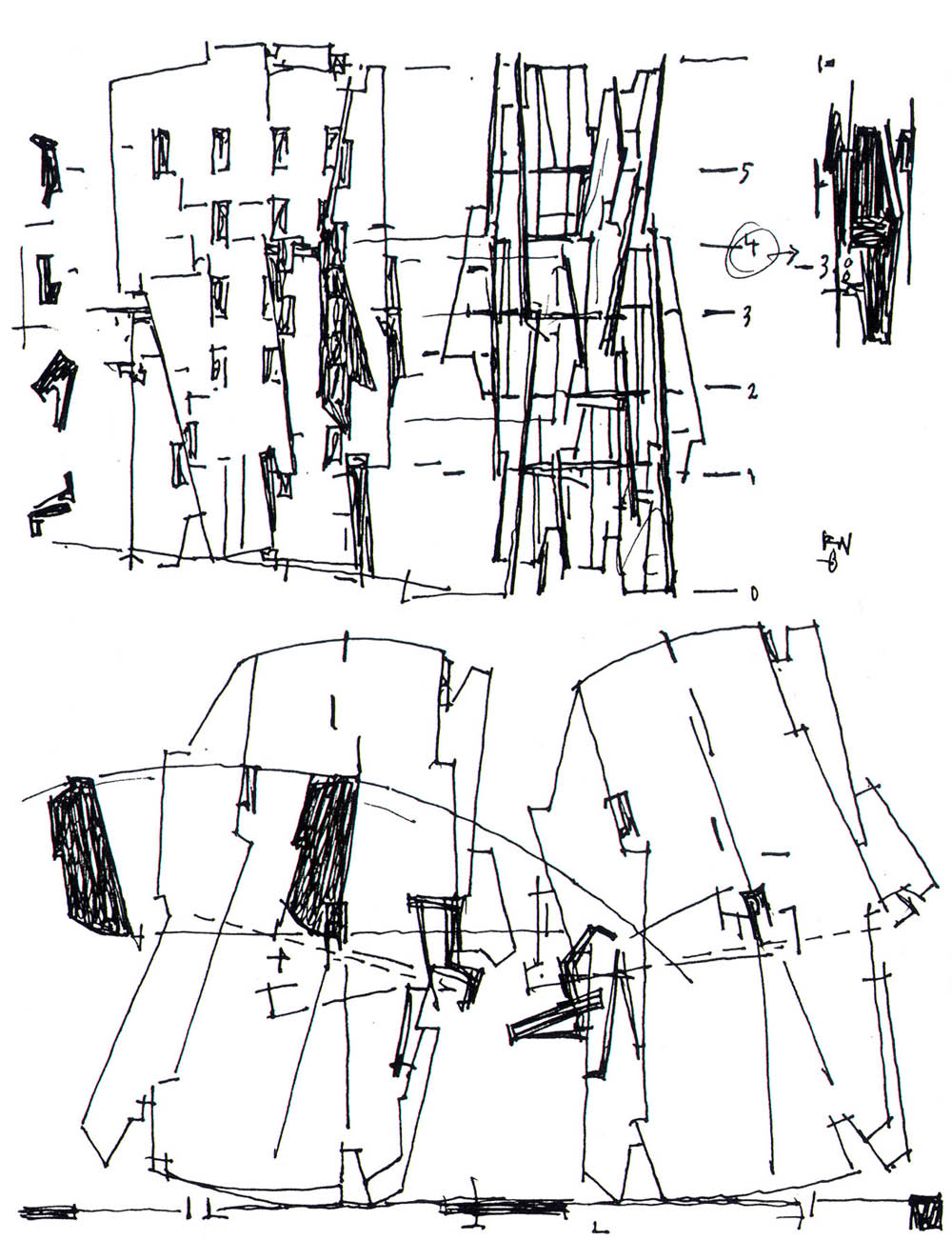

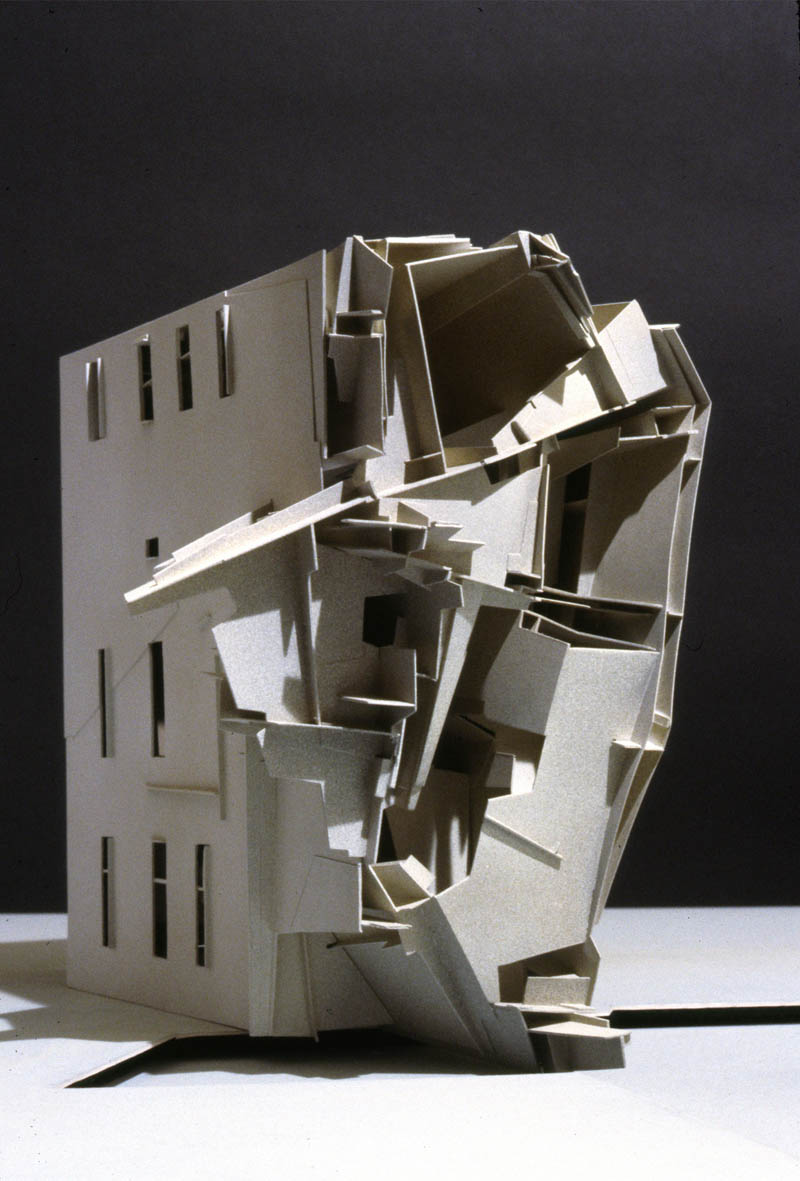

[Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods (with additional design and modeling by Paul Anvar)].

[Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods (with additional design and modeling by Paul Anvar)]. [Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods (with additional design and modeling by Paul Anvar)].

[Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods (with additional design and modeling by Paul Anvar)]. [Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods].

[Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods]. [Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods (with additional design and modeling by Paul Anvar)].

[Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods (with additional design and modeling by Paul Anvar)].

[Images: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods (with additional design and modeling by Paul Anvar)].

[Images: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods (with additional design and modeling by Paul Anvar)]. [Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods].

[Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods].

[Images: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods (with additional design and modeling by Paul Anvar)].

[Images: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods (with additional design and modeling by Paul Anvar)]. [Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods].

[Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods].

[Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods (with additional design and modeling by Paul Anvar)].

[Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods (with additional design and modeling by Paul Anvar)]. [Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods].

[Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods].

[Image: “

[Image: “

[Images: “

[Images: “

[Images: “

[Images: “

[Images: “

[Images: “

[Images: “

[Images: “ [Images: “

[Images: “

[Images: “

[Images: “

[Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

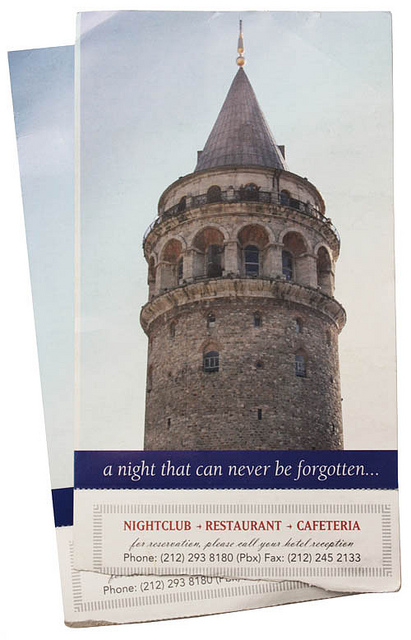

[Image:  [Image: Istanbul’s Galata Tower, as depicted on ephemera related to

[Image: Istanbul’s Galata Tower, as depicted on ephemera related to

[Images:

[Images:

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: New York’s

[Image: New York’s