[Image: Inside the Pantheon; via].

[Image: Inside the Pantheon; via].

Through both film editing and sound design, Walter Murch has worked literally behind the scenes of Hollywood to give shape and structure to the films we see. In the process, he’s won three Academy Awards; he’s directed his own feature-length film, the creatively subversive Return to Oz; and he’s worked with some of the greatest directors of modern times, including Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas, on some of their greatest films, from The Godfather trilogy and Apocalypse Now to The Conversation and THX-1138.

But it is due only in part to Murch’s stellar career in film that I wanted to talk to him for BLDGBLOG.

As it happens, Murch’s interests go far beyond the reach of cinema, encompassing architecture, astronomy, music theory, and mathematics – among an almost impossibly broad range of other subjects. When a friend of mine casually mentioned that Walter had “discovered” something about the Pantheon, in Rome, and that this discovery had something to do with Nicolaus Copernicus and the origins of heliocentrism in Western astronomy, I was determined to write about it for BLDGBLOG. Within only a few weeks, Walter and I were in touch.

Of course, Murch is already very well-known as an interviewee; as only one example of this, novelist Michael Ondaatje recorded an entire book’s worth of interviews with Murch, later published under the title The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film.

That book is never less than fascinating, if frequently enigmatic; at one point Murch claims, for instance, referring to his sound work for film: “If I go out to record a door-slam, I don’t think I’m recording a door-slam. I think I am recording the space in which a door-slam happens.”

Or, continuing that thought:

I spent a lot of time trying to discover those key sounds that bring universes along with them. I tend not to visualize but auralize, to think about sound in terms of space. Rather than listen to the sound itself, I listen to the space in which the sound is contained.

Murch and I spoke for roughly an hour, and we continued our conversation through email; we managed to discuss the Pantheon, Copernicus, the Mithraic religion of the ancient Mediterranean, urban acoustics, the music of the spheres, Brian Eno, Single Speed Design, the architecture of film, and whether CCTV surveillance of city streets should be considered a new cinematic avant-garde.

It’s worth noting, finally, that this interview goes online only a few hours before Murch is due to speak at an event in San Francisco, co-organized by BLDGBLOG and Chronicle Books; there, he will be discussing his thoughts on Copernicus and the Pantheon in more detail.

[Image: Exterior view of the Pantheon].

[Image: Exterior view of the Pantheon].

BLDGBLOG: I’d like to start with your research into the Pantheon – in particular, how that building’s structure may have influenced the astronomical theories of Nicolaus Copernicus. Could you tell me a bit more about that?

Walter Murch: Well, the Pantheon still holds its mysteries: Who designed it? How was it used? What does it mean? But Copernicus still has his mysteries, too: Why did someone like him, a high official in the Church, 500 years ago, dedicate his life to the idea that the Earth revolved around the Sun? Not only did this contradict common-sense and the teaching of the Bible, but it also capsized 1400 years of Ptolemaic, geocentric astronomy. And Ptolemy, it turns out, was writing his classic book on astronomy – the Almagest – while the Pantheon was being built.

At any rate, Copernicus was born in 1473. He studied astronomy at the University of Bologna, along with medicine and law, and while he was there he became an assistant to Domenico Novara. Novara was a well-known astronomer who may have exposed Copernicus to the 3rd century BC theories of Aristarchus.

Aristarchus believed that the Sun was the center of the universe. He also believed that the Earth not only revolved around the Sun, along with all the other planets, but that it rotated on its axis once every 24 hours, and that the moon, in turn, revolved around the Earth. So – more than two thousand years ago – Aristarchus described the solar system essentially the way we conceive of it today; yet his theory was rejected at the time, and his writings were subsequently lost.

Scholars in the Renaissance were only able to learn about Aristarchus through a book called The Sand Reckoner, by Archimedes, where Aristarchus’s theory is described – but it’s used as the premise for an impossibly large universe. Aristarchus’s heliocentrism is almost certainly the source of Copernicus’s inspiration – but why did Copernicus take it seriously when no one else did?

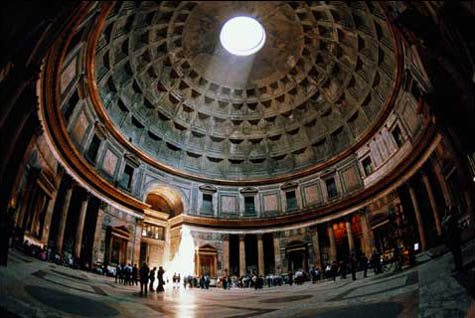

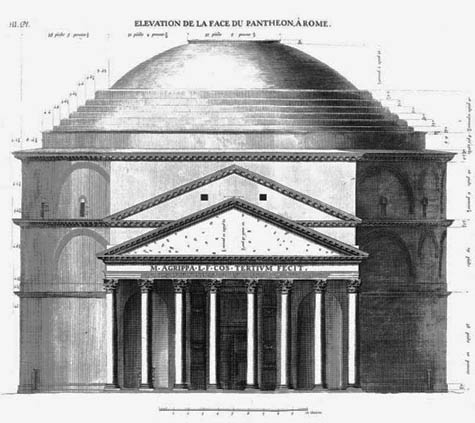

In 1500, a Jubilee year, Copernicus took time off from his studies in Bologna and he moved to Rome. This is where the Pantheon comes in. Circumstantial evidence would suggest that if you were a young man of 27, footloose in Rome, the Pantheon would be high on your list of places to visit: it was probably the most famous building in the world at that time – the only intact structure from Ancient Rome – and it featured the world’s largest dome: 142 feet in diameter. It remains, to this day, the largest unreinforced concrete dome in the history of architecture.

The Pantheon had survived mainly because it was consecrated in 609, yet the overwhelming feeling when you walk into that building is pagan: a series of concentric circles surrounding a single bright source of light – which is the oculus in the center of the dome. It’s pretty certain that the Pantheon was designed by the Roman Emperor Hadrian, and Hadrian was a Mithraist – a worshipper of the Sun.

The only writing about the Pantheon from around the time it was built appears in the History of Rome, by Dio Cassius. Dio Cassius mentions that some people believed the name Pantheon (which is Greek for all gods) came from the statues of the many different gods which decorated the building, “but my own opinion of the name is that, because of its vaulted roof, it resembles the heavens.”

That powerful image of the central source of sunlight surrounded by a series of concentric circles must have been an overwhelming experience for Copernicus, primed by his knowledge of Aristarchus. He would have been standing in a church (St. Mary All Martyrs) built 1400 years earlier as a pagan temple, looking up at Aristarchus’s theory “in the flesh” so to speak.

[Image: The dome of the Pantheon, a “celestogramme” by Wolfgang Wackernagel].

[Image: The dome of the Pantheon, a “celestogramme” by Wolfgang Wackernagel].

BLDGBLOG: Are there any writings or images by Copernicus that might prove he interpreted the building this way?

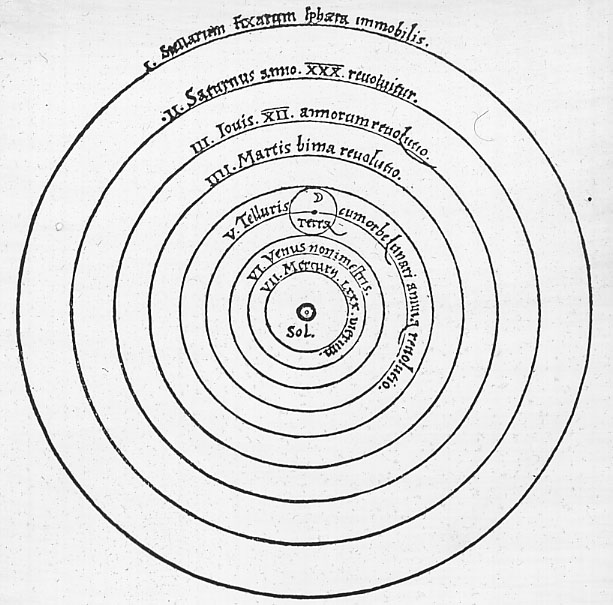

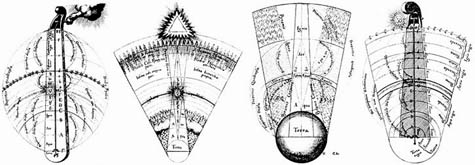

Murch: There is a drawing in Revolutions, at the end of Chapter Ten, where Copernicus, for the first time, schematically illustrates his conception of the Universe. It’s a series of concentric circles, the outermost being the “Sphere of the Fixed Stars,” with progressively smaller circles representing the orbits of Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Earth, Venus, and Mercury. In the center, of course, is the dot of the Sun. Copernicus’s exact words accompanying the drawing are significant:

At rest, however, in the middle of everything is the Sun. For in this most beautiful temple (in hoc pulcherimo templo) who could place this lamp in another or better position than the center, from which it can light up the whole at the same time? For, is not the Sun called ‘the lantern of the universe’ and, ‘its mind’ and by others ‘its ruler’? Hermes Trismegistus calls the Sun ‘a visible god’, and Sophocles’ Electra calls it ‘the all-seeing’. Thus indeed, as though upon a royal throne, the Sun governs the family of planets revolving around it.

What leaps out from that text are the allusions to this beautiful temple, illuminated by a central lamp – and lantern was the architectural term used in Copernicus’s time to refer to the central opening in a dome – which lights up the whole. Then there are the classical references to Hermes Trismegistus and Sophocles. These are not the words of a cautious medieval ecclesiastic, but someone deeply influenced by the ancient pre-Christian world.

[Image: A diagram of the planetary orbits, by Nicholas Copernicus].

[Image: A diagram of the planetary orbits, by Nicholas Copernicus].

BLDGBLOG: So, in that passage, he was simultaneously describing the structure of the Pantheon and his theory of the solar system?

Murch: In a sense.

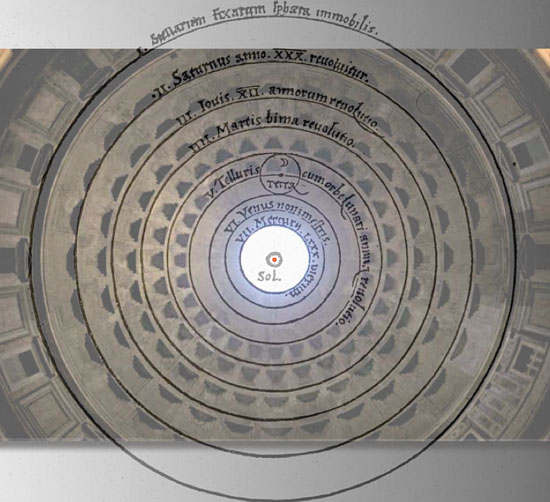

Inspired by that description, I then superimposed Copernicus’s drawing over an image of the Pantheon’s dome – and found that the ratios of the circles in his drawing and the ratios of the circles of the Pantheon line up almost exactly. Seeing that alignment was one of those wonderful moments where you suddenly feel a strong current of connection with the past.

[Image: A superimposition, by Walter Murch, of Copernicus’s diagram of planetary orbits over a celestogramme of the Pantheon by Wolfgang Wackernagel].

[Image: A superimposition, by Walter Murch, of Copernicus’s diagram of planetary orbits over a celestogramme of the Pantheon by Wolfgang Wackernagel].

BLDGBLOG: Wow! That’s not just a coincidence? Copernicus actually meant for that to happen?

Murch: The circumstantial evidence is compelling, but there is no reference to the Pantheon in any of Copernicus’s correspondence or in the various manuscript versions of de Revolutionibus – so we will probably never know for sure.

Nonetheless, it’s a fascinating thought: that this magnificent temple, built 1400 years before Copernicus ever saw it, designed by a pagan, Sun-worshipping Roman emperor, and later transformed into a church, may have had secretly encoded within it the idea that the Sun was the center of the universe; and that this ancient, wordless wisdom helped to revolutionize our view of the cosmos.

BLDGBLOG: As far as the organization of the solar system goes, you’ve also been doing some interesting work with Bode’s Law, which has to do with finding a mathematical pattern in the orbits of the planets. How did you first discover that Law, and where is your research going?

Murch: Well, it was something I ran across a number of years ago in Arthur Koestler’s book The Sleepwalkers – a history of our conception of the universe from ancient Greece through Copernicus, Kepler, and Galileo to Newton. Bode’s Law is just mentioned as a footnote.

Kepler, in particular, had been obsessed with finding a pattern in the orbits of the planets – his famous Three Laws were discovered almost incidentally along the way to that goal, and he would probably be very upset to find that we remember him for his those laws (which he did not number or particularly esteem) and that we’ve forgotten the planetary harmonics to which he devoted his life. But, even by the middle of the 1600s, Kepler’s harmonies were considered a lost cause.

Then, sometime in the 1760s – more than a hundred years after Kepler – a German professor of physics inserted a formula into a French book he was translating: a simple bit of algebra which seemed to indicate there was, indeed, a pattern to the planetary orbits. That professor was Johann Titius, and his formula was later appropriated and published by the director of the Berlin observatory, Johann Bode. Bode had a much bigger megaphone than Titius, so the formula became known as Bode’s Law – but it should really be named after Titius.

When I read Sleepwalkers I was right in the middle of finishing a film – and it was odd, because I was under a tight deadline, but this idea really got under my skin. So at 11:30 at night I started fooling around with the Bode numbers, and within half an hour, I came up with a formula that generated the same set of ratios, yet was different from the original – and that really made the hair on the back of my neck stand up! That was what started me down this road, about ten years ago.

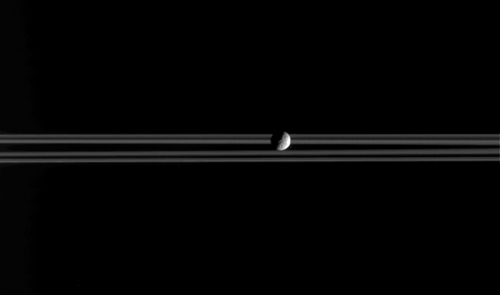

[Image: The rings of Saturn; courtesy of NASA].

[Image: The rings of Saturn; courtesy of NASA].

BLDGBLOG: What’s the specific idea behind the Law itself? In other words, what exactly is Bode’s Law?

Murch: It’s a relatively simple exponential function, sprinkled with a few arbitrary constants – you put whole numbers (1, 2, 3, 4, etc.) in at one end and a series of different numbers come out the other (.4, .7, 1.0, 1.6, etc.). It turns out that these new numbers are very close to the average distances of the planets from the Sun, measured in Astronomical Units (AU). For instance, the Earth is (by definition) 1 AU from the Sun. Bode’s Law says that there should be a planet at .7 of that distance – and Venus is actually found at .72 AU.

Titius’s formula not only correctly described – to within a few percentage points – the average distances of the six planets known at the time, but it also predicted that there should be planets at certain distances where there seemed to be empty space. Then, in 1781, Uranus was discovered – the first planet ever to be discovered with a telescope – and its average distance turned out to be 19.2 AU, within 2% of the predicted 19.6. In 1801, Ceres, the first and largest asteroid, was discovered at 2.77 AU, within 1% of the predicted 2.8.

It was a kind of astronomical apotheosis: Titius’s formula seemed to be both descriptive and predictive: the holy grail of science. It fit all the known planets – even newly-discovered ones. So, even though nobody knew why it worked, Titius’s formula was assumed to be a Law. Unfortunately for Titius, who died in 1796, it became popularly known as Bode’s Law.

Everything was fine for the next fifty years, but then disaster struck: in 1846, another new planet was discovered – Neptune – but it didn’t fit. It should have been at 38.8 AU, but it was orbiting at 30, off by almost 30%.

It was a fatal blow. Bode’s Law fell into obscurity, where it remains to this day. Now, when you take astronomy 101, if Bode’s Law is mentioned at all, it’s presented as a historical curiosity. Or a cautionary tale of wrong thinking – luring unwary astronomers into the swamp of numerology.

But, then, when Pluto was discovered in 1930, it fit to within 2% the orbit where Neptune should have been. So rather than throw the whole thing out because one planet didn’t fit, I thought it would be interesting to set Neptune aside as a renegade and see what I could learn by applying the formula to other orbital systems.

I eventually discovered that there are parts of the formula that are linked to particular and unique aspects of our own solar system – and that these particularities are responsible for some of the arbitrary constants in the formula. I found if I could purify the formula of these constants, then I could also make it simpler and more general, and yet it would still yield the same set of ratios.

[Images: The rings – and a moon – of Saturn; courtesy of NASA].

[Images: The rings – and a moon – of Saturn; courtesy of NASA].

BLDGBLOG: How did you purify it?

Murch: Well, one of the unexamined assumptions in Bode’s Law is that the unit to which everything is mathematically compared is the distance of the Earth from the Sun. This seems perfectly natural – it’s the Astronomical Unit, and the Earth is where we live. But this comparison requires the formula to perform a kind of mathematical jiu-jitsu: it has to generate a series of ratios and compare all of those ratios to the Astronomical Unit.

So it seemed more logical to abandon the Astronomical Unit and just concentrate on the ratios. Once you do that, the formula gets much simpler: it doesn’t have to do two things at once. This new formula is not only simpler, but it’s also lost its “Earth-centricity.” Now you can apply it to other orbital systems – the miniature “solar systems” of the moons around Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune, for instance, and you find the same set of ratios cropping up!

Of course, it’s not that the moon systems of those planets somehow duplicate the solar system – they don’t. It’s rather that, underlying all of these moons and planets, there is a pattern of ratios, like the musical ratios underlying a keyboard. Just as you are restricted to playing certain musical ratios on a keyboard, so it seems to be with the arrangements of these moons. Some systems “play” – or occupy – certain orbits that others don’t.

Applying the same formula to different systems is potentially very fruitful. By comparing orbital systems you find that, in each of system, there are a few renegades – like Neptune in our solar system – but each of these is a renegade in the same way as Neptune: all of them fall exactly at the midpoint between two adjacent Bode-predicted orbits. So there is an underlying similarity even to the exceptions.

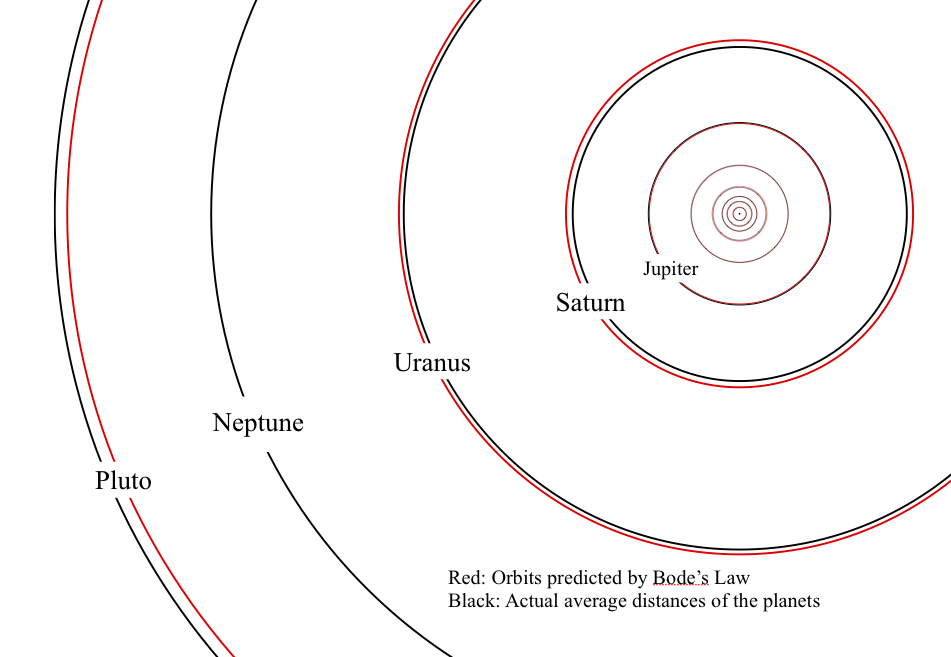

[Image: Bode-predicted planetary orbits compared to those orbits as they are now scientifically understood].

[Image: Bode-predicted planetary orbits compared to those orbits as they are now scientifically understood].

BLDGBLOG: The “music of the spheres” is perhaps an inevitable metaphor to use here – but I’m curious if you have actually found a real, numerical correspondence between the structure of Western music and the orbits of the planets, or if it’s just a convenient metaphor.

Murch: That’s one of the startling things about this. If I wrote the simplified Bode formula down on a piece of paper and showed it to music theorists, they would ask: “Why are you showing us a formula from the overtone series…?”

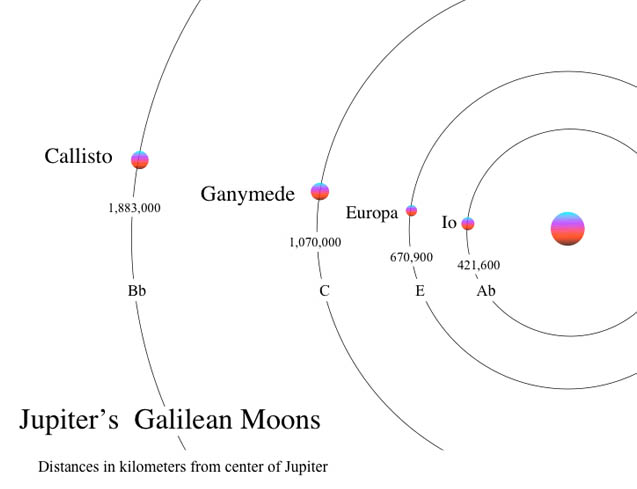

In other words, Bode’s Law gives a series of orbital ratios which are mathematically identical to intervals in musical theory. They’re primarily variations on what we call the 7th chord: C, E, G, B-flat. Bode’s predicted ratio between Earth and Mars, for instance, is the same as the 5:8 musical ratio between E and C. And if you divide the distances, in kilometers, of the four Galilean moons by a common denominator you get the notes Ab, E, C, Bb. And so on.

[Image: The moons of Jupiter].

[Image: The moons of Jupiter].

BLDGBLOG: Have you discussed these ideas with actual astronomers? How did they react?

Murch: I’ve given this, as a lecture, in various forms – at the National Convention of Digital Astronomy in Italy in 2004; at NYU in 2005; and then, last year, at the Chicago Humanities Festival. I think it was well-received in each case, but it’s still a work-in-progress, and I’m looking for feedback from people who are interested in this kind of cross-disciplinary thinking. For most astronomers it’s hard to contemplate reviving a long-discredited 18th century law of celestial mechanics, let alone the music of the spheres! [laughs] The conventional wisdom about Bode’s Law is that it’s just a fluky coincidence.

[Images: The world as a series of chords; via].

[Images: The world as a series of chords; via].

BLDGBLOG: So there are similarities between this and music theory – but what about between this and film theory? Is there a kind of Bode’s Law of film editing? The relationships between scenes and so on?

Murch: I think the common thread to both astronomy and film-editing is this search for patterns. Now, at least as far as we can tell, filmmaking is not amenable to the same kind of mathematical rigor that applies to astronomy [laughs] – there may be a mathematical rigor, but we certainly haven’t discovered what it is yet.

Think how difficult it would be to explain musical notation to someone from ancient Egypt, when they did not even suspect the underlying mathematical laws of harmonics, let alone a way of writing it all down. Instead, for thousands of years, music was the main poetic metaphor for that which could not be preserved. Music evaporates as soon as it is performed. So this idea – that marks could be made on paper, and that this paper could then be sent hundreds of miles away, allowing different people to play the same music years later – I think would have seemed very strange, even impossible, to people in ancient times.

Maybe someday, though, we’ll turn a conceptual corner and suddenly discover the equivalent of musical theory and notation in film. Maybe we are still “Ancient Egyptians” in that regard.

BLDGBLOG: When you’re actually editing a film, do you ever become aware of this kind of underlying structure, or architecture, amongst the scenes?

Murch: There are little hints of underlying cinematic structures now and then. For instance: to make a convincing action sequence requires, on average, fourteen different camera angles a minute. I don’t mean fourteen cuts – you can have many more than fourteen cuts per minute – but fourteen new views. Let’s say there is a one-minute action scene with thirty cuts, so that the average length of each is two seconds – but, of those thirty cuts, sixteen of them will be repeats of a previous camera angle.

Now what you have to keep in mind is that the perceiving brain reacts differently to completely new visual information than it does to something it has seen before. In the second case, there is already a familiar template into which the information can be placed, so it can be taken in faster and more readily.

So with fourteen “untemplated” angles a minute, a well-shot action sequence will feel thrilling and yet still comprehensible: just on the edge of chaos, which is how action feels if you are in the middle of it. If it’s less than fourteen, the audience will feel like something is lacking, and they’ll disengage; if it’s more than fourteen, so much new information is being thrown at the audience that they’ll also disengage, though for different reasons.

At the other end of the spectrum, dialogue scenes seem to need an average of four new camera angles a minute. Less than that, and the scene will seem flat and perfunctory; more than that, and it will be hard for the audience to concentrate on the performances and the meaning of the dialogue: the visual style will get in the way of the verbal content and the subtleties of the actors’ performances.

This rule of “four to fourteen” seems to hold across all kinds of films and different styles and periods of filmmaking.

BLDGBLOG: Returning to the idea of music and sound for a moment, are there any places or buildings that you’ve visited, anywhere in the world, that particularly seemed to highlight the connection between a space and the sounds that occur in it? A kind of acoustic urbanism, where how a place sounds totally transforms what you see happening there?

Murch: Actually, I had that exact experience – but it was while watching a film. [laughter] Grand Central Station had been used as a location for one of the scenes. And this was despite the fact that I grew up in Manhattan, had been in Grand Central many times, and had developed an interest in sound recording as a teenager. But I was deaf to the kind of acoustic urbanism you’re speaking of until I saw Seconds by John Frankenheimer, in 1965.

There was just a single hand-held shot gliding down the main staircase, but accompanied by this…. bwoooaaahmmmm… the sound of that great room in all its wonderful complexity. It hit me very hard, emotionally, even though in retrospect it was quite obvious: the realization that you could join a certain tonality with a certain architectural space to create an emotion in the audience. And, if you wanted to, that you could then manipulate or distort that tonality to create a different sense of the visual space and a different emotion.

I’ve been pursuing that idea ever since. On every film I try to think as deeply as I can about the implied acoustic space of each scene; I then try to tailor the reverberant quality of the sound, and the tonality, to the spaces that we’re looking at. It’s endlessly fascinating, particularly because this technique flies “below the radar” of the audience. The filmmaker can have an effect on the audience without the audience knowing where that effect is coming from. Which I would guess is something that architects enjoy playing with, too.

[Images: Grand Central Station; via].

[Images: Grand Central Station; via].

BLDGBLOG: As far as an acoustically rich space goes, is there a specific place – or a building or a landscape – where you like to record sounds for use in a film? How does the actual space affect the sounds you can record in it?

Murch: Well, first of all, I record a sound without any atmospheric envelope around it. I then take that recorded sound and find an acoustic space that is as close as possible to the acoustical space in the film; I play the sound in that space; and I record the resulting reverberation on another device, placed to extract the maximum reverberation. Then, in the final mix, I have the ability to blend those two sounds: the “dry” sound itself, alongside a sound which is almost all reverberation.

In musical terms, you could say it’s like the relationship between the string of the violin and the reverberation and amplification added by the body of the violin itself.

By first separating and then balancing those two elements together, I can custom-fit what seems to be the right dimension of sound implied by the space on screen. If you have too much reverb, and you don’t hear enough of the original sound itself, the result is too diffuse and ethereal to be realistic – but sometimes that lack of realism is exactly what you want. On the other hand, if you play proportionately too much of the dry sound, it doesn’t seem to connect to the space you’re looking at. But maybe that’s exactly what you want – that kind of dislocation. It all depends on the dramatic intent of the moment. But these two elements give you the handles to control the final result.

Over the last forty years, this time-consuming technique of physically “worldizing” the sound has been gradually replaced by increasingly sophisticated digital techniques, though the principle is the same. Now we can record a digital “snapshot” of a real acoustic space, using tone bursts and frequency sweeps, and then impose the resulting parameters on any sound we want, back in the studio.

BLDGBLOG: In a still unpublished interview I did with a Boston-based architecture firm called Single Speed Design, I asked one of the principal designers whether he liked ambient music – and his answer was interesting. He said that he didn’t like ambient music at all because it already included all the reverb, echo, and other effects that should have been introduced by the space in which the music was played. In other words, ambient music does the work of architecture for you, on the level of acoustics.

Murch: Exactly. He was reiterating, in an architectural sense, exactly what we do as a sound recordists.

BLDGBLOG: Another anecdote I think is interesting here comes from the British composer Brian Eno. Eno once said that he would make field recordings in different parks around London, then listen to the tapes until he’d memorized them – the way you would memorize a Beatles song. So he would know exactly when the church bell rang, and the mother called out to her child, and the birds flew overhead – or a distant truck rumbled by. He memorized the space according to the sounds that occurred within it.

Murch: There’s a wonderful essay by Michelangelo Antonioni, notes for a film that he was going to make in New York. To familiarize himself with the acoustic space of Manhattan (where he had never made a film) he sat in a room 34 stories up in a hotel somewhere on Fifth Avenue, writing down exactly what he heard over a period of three hours from dawn through rush hour. He came up with the most wonderful metaphors for sounds that were mysterious and unfamiliar to him, but which would be run-of-the-mill to a New Yorker. It’s a great read: a kind of meditative poetry, or song, just like Brian Eno said. It can evoke a whole series of emotional responses if you’re sensitive to that kind of stuff.

BLDGBLOG: Speaking of which, is there a specific place, like Leicester Square or some forest near San Francisco, where you thought to yourself: I could do this better – I could make this place sound better?

Murch: [laughs] Back in the late 60s we used to think of hiding a series of playback devices around a house to improve the sounds of the doors closing, the toilets flushing, and so on. Creating a real-life alternate acoustic universe.

Certainly the dominant thing that’s happened over the last hundred years is the universal spreading of white noise – just the general mush of traffic, air-conditioning, and jet planes. Whereas if you were in Leicester Square a hundred years ago, it might have been just as noisy – but the sounds would be more specific, less mushy and ill-defined because of the lack of the internal combustion engine and the constant whir of rubber tires on asphalt. For a number of years Aggie and I lived very near a freeway, on a Sausalito houseboat, and that constant mushy sound eventually became a kind of water-torture for me.

So I don’t have a specific answer for your question – but, generally, it would be to try to find some way to eliminate the white noise and to make people more sensitive to the individual sources of sound and reverberations within the space. Church bells can do that: they attract the ear with their tonality and reverberation, making you aware of the space between you and the church, and making you less aware of the underlying white noise.

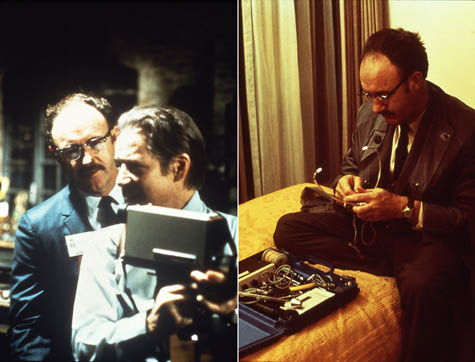

[Image: Harry Caul (Gene Hackman) gets to know his surveillance equipment; from The Conversation. Courtesy of American Zoetrope].

[Image: Harry Caul (Gene Hackman) gets to know his surveillance equipment; from The Conversation. Courtesy of American Zoetrope].

BLDGBLOG: Finally, I’m curious how you, as a film editor, see the rise of video surveillance – CCTV – in cities around the world. It seems that cinema has become the default condition of urban security. So I have two questions: do you think that a new kind of cinematic avant-garde is evolving in the control rooms of private security firms? In other words, these epic, nine-hour shots of parking lots seem more Warholian than Andy Warhol. And, second: if you were suddenly faced with all of the surveillance footage generated in a city for a day, do you think you could edit it into a convenient, albeit imaginary, narrative? You could take all those non-events and edit them into something – with action, and a storyline, and rhythm?

Murch: Well, there was a short film made a few years ago where the filmmaker had worked out the location of all the surveillance cameras along a cross-section of London, and how many of those cameras were operated by the municipal authorities. If the cameras were operated by the city, then he could get access to the footage. So he mapped out a pedestrian trip for himself across town knowing that, at every moment he would be on CCTV: as soon as he was out of range of one camera, he would come into focus on another. So he walked the walk, wrote to all the relevant authorities, got the footage, and then edited it all together into a continuous narrative. It’s very amusing in a dystopian, Warholian kind of way. You only “get” the joke after a few minutes of watching.

But George Lucas’s THX-1138 was kind of like that, except it was made in 1971. Much of the action takes place on video surveillance cameras. In fact, the job of the girl in the film is to monitor banks of surveillance cameras. She eventually gets fed up, stops taking her Prozac, or whatever, and tries to escape this completely video-monitored world – which, it turns out, is completely underground because of some disaster that had happened on the surface many years earlier.

Also similar, in some ways, is The Conversation – which is about audio surveillance – made around the same time. Part of the visual style of that film was a dispassionate “surveillance camera” look. There are a number of moments in the film where Gene Hackman walks into the shot, lingers for a moment, and then he walks out – but the camera doesn’t follow him or cut, as it normally would. Until, maybe five or ten seconds later, it slowly pans left, in a very mechanical way, over to where he is, and then it watches him for a while. But then he gets up and moves out of range again, and so on.

This is all in 35mm, not video, but the effect is disorienting just the same – perhaps even more so. It’s as if the camera has a motion-detector behind it, not an intelligence. It will stay still as long as there is activity – but then, if it detects a lack of activity, it will wait five seconds before searching out where the activity might have gone. The film both begins and ends like that – a long slow mechanical zoom at the beginning, then ending on an oscillating camera that pans back and forth mindlessly. And there are a number of scenes in the middle that are shot similarly.

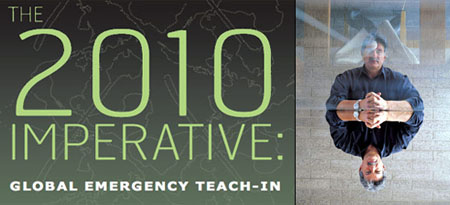

[Image: Harry Caul (Gene Hackman) realizes his apartment is bugged; from The Conversation. Courtesy of American Zoetrope].

[Image: Harry Caul (Gene Hackman) realizes his apartment is bugged; from The Conversation. Courtesy of American Zoetrope].

BLDGBLOG: So do you think that video surveillance is a kind of unacknowledged form of cinema, or even a counter-Hollywood on the rise? The next avant-garde?

Murch: Something may be emerging. For instance, Mike Figgis’s Timecode is similar in its use of the simultaneous action of a four-way split screen telling four stories which sometimes interconnect.

You know, the other aspect of this is that these CCTV images are recycled and abandoned regularly. They are preserved for a certain length of time, and then they’re obliterated if there is no call for them. There is a temporality to it all which I think needs to be taken into account. It’s amazing, when you think about it, how rapidly this technology has spread – for economic reasons that have nothing to do with creativity. Insurance companies will now put cameras up at intersections where there have been lots of accidents. Then, if there is an accident involving one of their clients, they can use the footage to prove that the other person is at fault. Even when their client may be dead. Especially when he is dead.

BLDGBLOG: [laughs]

Murch: There’s also footage now being made available, showing the July 7 London bombers rehearsing their terror plan two weeks ahead of time – all caught on publicly-operated CCTV cameras – and it is almost like the first example I mentioned, of crossing London on foot – lots of continuity of action. Except that it was real, and many lives were lost.

One hope I have is that someone will put a HiDef camera into orbit, giving a full-frame view of the Earth spinning below, and this will be made available to everyone on HiDef cable channel 427 or whatever. Then, when plasma screens – or liquid crystal, or digital wallpaper – get large enough, this image can then occupy the entire wall of a room in your house. You’ll be able to go into that room and do other things – read a book, or listen to music, and occasionally look up – and one entire wall of the room is the Earth as it actually is at the very moment that you’re looking at it. It would be as if your room were in orbit.

You’d begin to see Earthly events in context – a volcanic eruption in Peru, or the pollution coming out of New York harbor, or the hurricane threatening New Orleans, floods in Bangladesh – and it will begin to change our awareness of our relationship to the Earth in a profound way, the way the mirror changed our relationship to ourselves, and deepened our sense of identity as individuals. Given the technology that we have today, I’m interested that it hasn’t already happened yet. Given the state of the world at the moment, I hope it happens soon.

[Image: The Earth; image courtesy of NASA].

[Image: The Earth; image courtesy of NASA].

I owe an enormous thank you to Walter Murch, both for taking the time to do this interview – even following up via email from London – and for speaking at BLDGBLOG’s event, co-organized by Chronicle Books, tomorrow afternoon in San Francisco. If you’re anywhere nearby, be sure to stop in.

I also owe a huge thanks to Lawrence Weschler for first putting me in touch with Walter, and for introducing Walter to BLDGBLOG; and to Anne-Marie Cowsill, Chad Keig, and James Mockoski at American Zoetrope for sending me images from the filming of the The Conversation. Finally, I want to thank my wife, Nicola, for helping edit all this together while we drove up to San Francisco – it was also Nicola who suggested the interview’s title.

Meanwhile, I would urge anyone even remotely interested in the topics covered by this interview to pick up a copy of The Conversations. It’s compulsively readable, and well worth the time. Murch’s own book, In the Blink of an Eye, is particularly useful for anyone working in film.

Finally, Charles Koppelman’s Behind the Seen: How Walter Murch Edited Cold Mountain Using Apple’s Final Cut Pro and What This Means for Cinema is a detailed look at the film-editing experience itself, focusing on Murch’s decision to use an off-the-shelf software package in the editing of Anthony Minghella’s Cold Mountain.

[Image: Ole Bouman, photographed by Cassander Eeftinck Schattenkerk].

[Image: Ole Bouman, photographed by Cassander Eeftinck Schattenkerk]. BLDGBLOG: In

BLDGBLOG: In  BLDGBLOG: Again in

BLDGBLOG: Again in  [Image: The CCTV building, Beijing, by Rem Koolhaas/

[Image: The CCTV building, Beijing, by Rem Koolhaas/ BLDGBLOG: I’m interested in your work – and

BLDGBLOG: I’m interested in your work – and  BLDGBLOG: When you go there, who exactly are you networking with? Architects? Civil servants?

BLDGBLOG: When you go there, who exactly are you networking with? Architects? Civil servants?

BLDGBLOG: Finally, as far as your new job goes – becoming

BLDGBLOG: Finally, as far as your new job goes – becoming  [Image: (Right) Ed Mazria, photographed by Doug Hoeschler for

[Image: (Right) Ed Mazria, photographed by Doug Hoeschler for  [Image: A chart of Architecture 2030’s goals; via

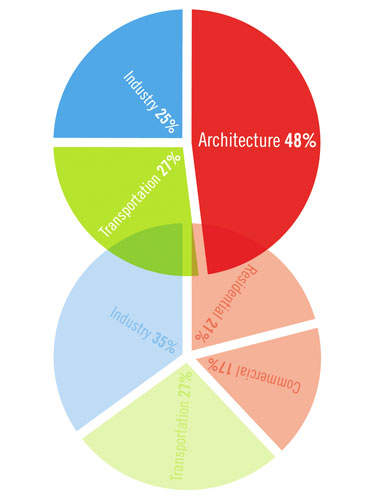

[Image: A chart of Architecture 2030’s goals; via  [Image: “U.S. Energy Consumption by Sector. A reorganization of existing data – combining the energy required to run residential, commercial, and industrial buildings along with the embodied energy of industry-produced materials like carpet, tile, and hardware – exposes architecture as the hidden polluter.” Graphic by Criswell Lappin, via

[Image: “U.S. Energy Consumption by Sector. A reorganization of existing data – combining the energy required to run residential, commercial, and industrial buildings along with the embodied energy of industry-produced materials like carpet, tile, and hardware – exposes architecture as the hidden polluter.” Graphic by Criswell Lappin, via  [Image: The interior of Ed Mazria’s New Mexico home, designed by

[Image: The interior of Ed Mazria’s New Mexico home, designed by  [Image: Skylit gymnasium in Genoveva Chavez Community Center, Santa Fe; designed by

[Image: Skylit gymnasium in Genoveva Chavez Community Center, Santa Fe; designed by  BLDGBLOG: The

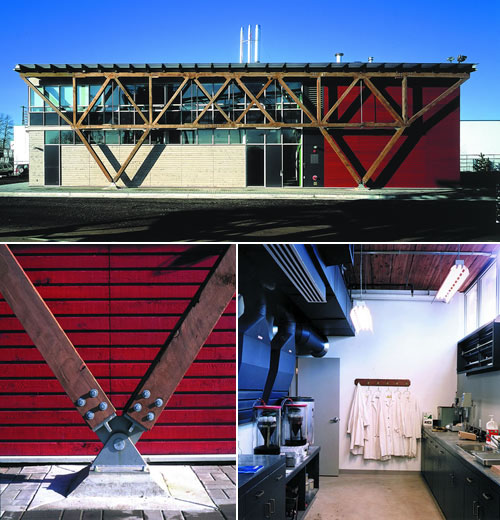

BLDGBLOG: The  [Image: Materials Testing Facility, Vancouver, designed by

[Image: Materials Testing Facility, Vancouver, designed by  [Image: School of Nursing and Student Community Center, Houston, designed by

[Image: School of Nursing and Student Community Center, Houston, designed by  [Image: Energy Savings Buildings, Albuquerque; designed by

[Image: Energy Savings Buildings, Albuquerque; designed by  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

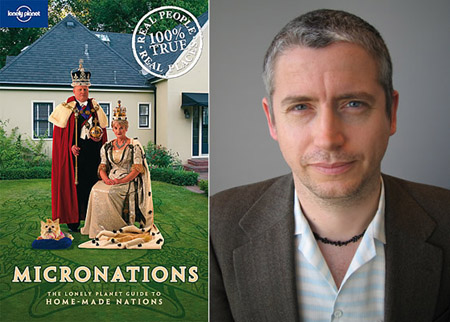

[Image:  [Images: The book and one of its authors,

[Images: The book and one of its authors,  [Image:

[Image:  [Images: The

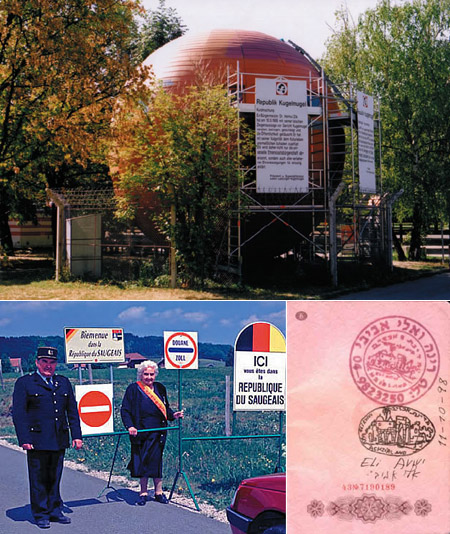

[Images: The  [Images: Kevin Baugh, President of the

[Images: Kevin Baugh, President of the  [Images: Emperor Georgius II of the

[Images: Emperor Georgius II of the

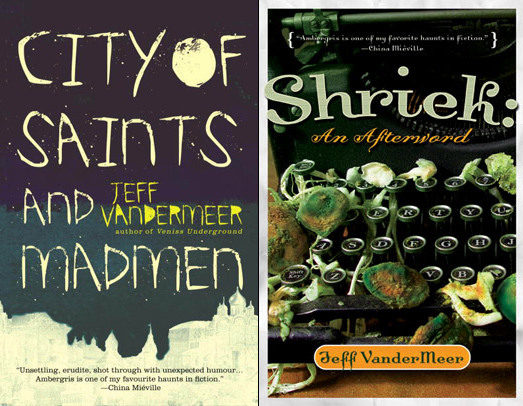

[Image: Interior view of the

[Image: Interior view of the

[Image: Gormenghast castle; from the

[Image: Gormenghast castle; from the