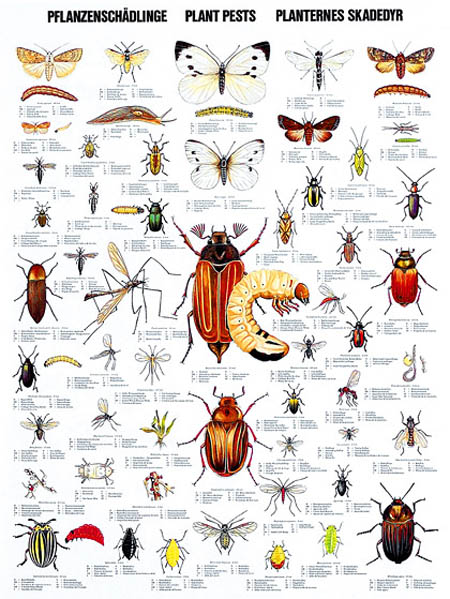

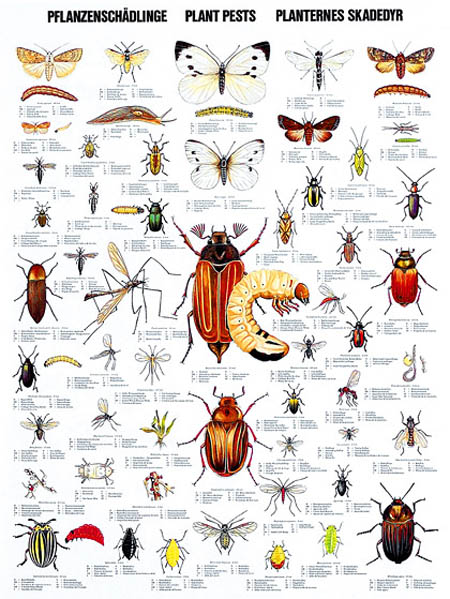

[Image: 55 of Europe’s most common plant pests in a wall poster found via the Scandinavian Fishing Year Book].

[Image: 55 of Europe’s most common plant pests in a wall poster found via the Scandinavian Fishing Year Book].

Sara Redstone is Plant Health and Quarantine Officer for the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, home of the world’s largest collection of living plants. In addition to screening and isolating all incoming or outbound plant material, she is currently overseeing the design and construction of a new quarantine facility for the gardens.

As part of our ongoing series of quarantine-themed interviews, Nicola Twilley of Edible Geography and I visited Redstone at Kew, where we drank tea outside the Orangery café. Over the course of nearly two hours, we talked about the impact of current and potential pest outbreaks, the ecological risks of open E.U. borders and global trade, and the complicated governmental infrastructure of plant protection. In addition, we touched on what plant quarantine at Kew actually looks like, in terms of the functional and technical challenges involved in Wilkinson Eyre Architects‘ design for a new Quarantine House. Along the way, we covered plant smuggling, invasive species, and the potential to create a Sudden Oak Death super-strain.

[Image: A diseased pear from the USDA Pomological Watercolor Collection].

[Image: A diseased pear from the USDA Pomological Watercolor Collection].

• • •BLDGBLOG: What do plant quarantine measures encompass—invasive species, plant diseases, or even genetically modified organisms? And who is in charge of enforcing plant quarantine in the UK?

Sara Redstone: Plant quarantine at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, is concerned with controlling plant pests and diseases, to protect our living collections and the wider environment. In the UK, a number of different structures govern plant import restrictions, monitor invasives, and issue licenses for quarantine and for genetically-modified organism—GMO—research. The rules for working with GMOs are laid out and policed by the Health and Safety Executive, but issues that relate to plant health, quarantine, and potential pests and diseases of plants are actually monitored and controlled by an organization called FERA (the Food and Environment Research Agency), which is a new agency within DEFRA (the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs).

It can get quite complicated! Different organizations deal with plant health issues depending on where the plants grow and what they are. Unfortunately, the type of information you can get online relating to plant health and quarantine is not always very user-friendly. For example, inquiries about plant health, imports, and restrictions in Scotland go to the Scottish Office, but in England they either go to FERA or the Forestry Commission, depending on the type of organism. Licenses to operate quarantine facilities depend on what type of material you are quarantining (plant or animal), the purpose of raising such material (to grow the plant itself or to grow potential pests or diseases), and various other factors. Meanwhile, GMOs fall under the Health and Safety Executive, as I said—but inquiries about GMO regulations go to DEFRA.

Ordinary members of the public quite understandably find this very confusing.

Edible Geography: What are some of the most worrying issues facing you in terms of plant pest control?

Redstone: One particularly nasty tree pest, which is also a potential human health hazard, is the Oak Processionary Moth. Kew is just one of many locations in southwest London that has experienced this pest. Like the Browntail and other moths, during various stages of their life-cycle the caterpillars are covered in really brittle hairs that have a toxin in them. It can give you a nasty rash and may cause breathing difficulties or affect your eyes on contact.

The moth came into the UK as eggs on imported trees from Holland—and the challenge we face is that we don’t typically quarantine trees from northern Europe. There is no legal requirement to quarantine material from within the EU, but the pest is widespread in the Benelux countries and in Germany, and it is increasing its range on the mainland.

[Images: (left) The Oak Processionary Moth, pictured in a 2007 Daily Mail article titled: “Gardeners are mercilessly hunting down moths with hairspray and flame-throwers.” (right) Tree infested with Oak Processionary Moth caterpillars. Photo taken by Ferenc Lakatos, University of West-Hungary; found via the Centre for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health’s Bugwood Network].

[Images: (left) The Oak Processionary Moth, pictured in a 2007 Daily Mail article titled: “Gardeners are mercilessly hunting down moths with hairspray and flame-throwers.” (right) Tree infested with Oak Processionary Moth caterpillars. Photo taken by Ferenc Lakatos, University of West-Hungary; found via the Centre for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health’s Bugwood Network].

What happens is that many Dutch, Belgian, and German nurseries raise trees and shrubs in southern Europe, in areas such as Italy, where the Oak Processionary Moth is already established. The climate and local conditions promote better growth than can be achieved in northern areas, so you get bigger plants faster. They then move the plants back north to grow them on the nursery for a period of time, to get the right shape, etc. This kind of movement of plants has resulted in a lot of pests increasing their range and moving northwards.

Once a pest is established in a those northern mainland European states, there’s no way to prevent it from spreading to the others—because there are no real boundaries. There are no geographic features that are going to prevent them from moving, and there are no trade barriers that are going to stop them, either.

Although Britain is an island, everything is very much geared toward free trade; unfortunately, quarantine is usually secondary to trade. Most people involved in pest & disease control and quarantine will tell you that we like to employ what we call “the precautionary principle”—but, for political and economic reasons, governments don’t always choose to operate that way.

One of my concerns is that we know about these tree movements on the European mainland, and we know that the Citrus Long-horned Beetle, for instance, is now fairly well established in the Lombardy district in Italy—which is not that far from some of the major tree-growing areas in Tuscany. But what’s going to prevent those Long-horneds from spreading to northern Europe, given the movement of plants, and then coming over to the UK?

We’ve already had an instance where infested Acers were grown in China, shipped over to mainland Europe, and then sold in the UK. The beetle has a long larval phase—two to three years when it is undetectable by normal means, though I understand stethoscopes are now being used by some plant inspectors in an effort to detect larvae feeding. Usually the only way to detect them is finding the emergence hole in the tree base—or finding the adult beetle, after the fact. Were all the infested trees found? Were all the beetles present in the consignment destroyed? We don’t even know where all those plants have gone. It’s really bad news.

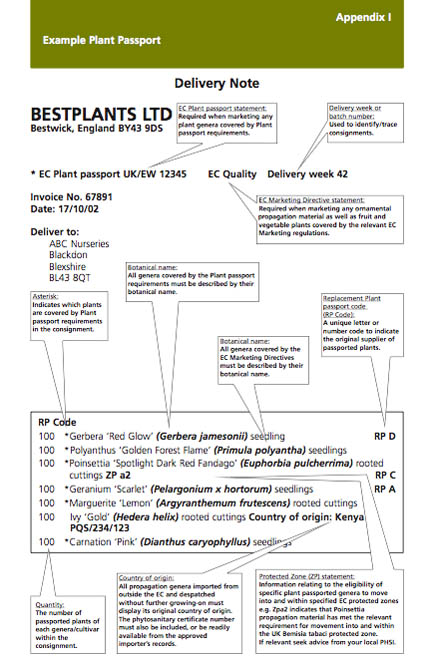

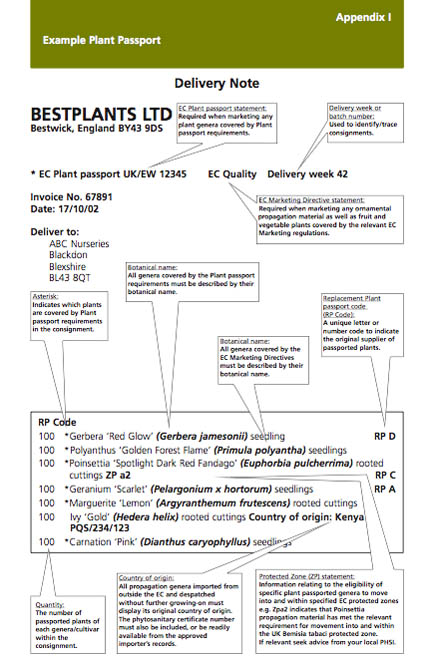

[Image: Sample “Plant Passport” from DEFRA’s Plant Health Guide to Plant Passporting].

[Image: Sample “Plant Passport” from DEFRA’s Plant Health Guide to Plant Passporting].

BLDGBLOG: What sort of measures are in place to deal with these threats?

Redstone: Material that comes in from the European Union is generally uncontrolled. There are “Plant Passport” regulations that apply to certain types of plant, but there’s no record of exactly what plant material is moving and where it’s from.

For instance, even if it says it is from, say, Holland, it doesn’t mean that that material originated in Holland. It may have arrived via Holland in a container ship from China.

Different countries have different standards for quarantine and plant health. You can understand that, in some countries where it’s really a struggle to make a living, different rules apply. There is an organization called the International Plant Protection Committee (IPPC), which makes recommendations—but there is a real lack of shared standards for plant quarantine.

One thing that would be really useful now would be a series of suggested blueprints for quarantine buildings. For example, quarantine houses in places like the tropics can be relatively simple: mesh-screen, poly-tunnel-type structures with restricted access are fine. You don’t always have to use chemicals to sterilize things—in the tropics, you can use heat. Even in the UK, we can quite often use solar gain in our glasshouses to sterilize an area, provided we know what we’re trying to kill. The same methods have been used for years in agriculture; farmers will put polythene over an area of land, and then rely on the sun to sterilize the soil.

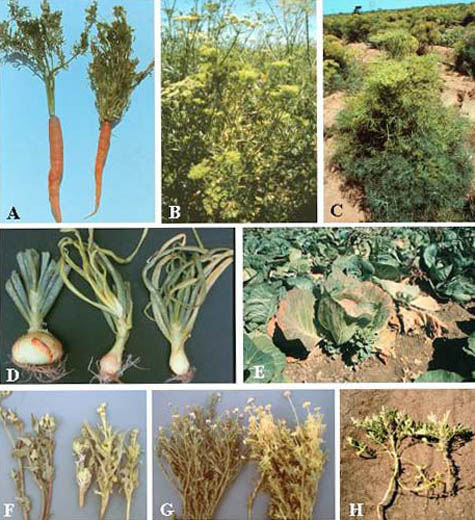

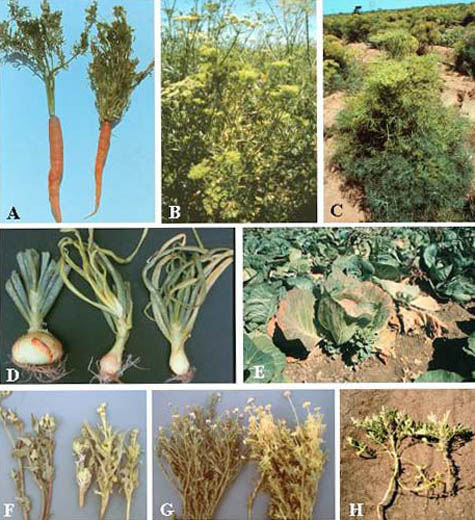

[Image: Healthy and diseased plants in a side-by-side comparison, via the USDA Agricultural Research Service].

[Image: Healthy and diseased plants in a side-by-side comparison, via the USDA Agricultural Research Service].

Edible Geography: Here at Kew, what is it that you are quarantining? Why does Kew need a quarantine house?

Redstone: We use plant quarantine—isolating, screening, and treating plants—for incoming and outgoing plants where we’ve determined they may be a risk associated with their movement. For example, if we want to repatriate material to a country as part of a conservation project, the last thing we would want to do is inadvertently introduce a new pest or disease; so we isolate and treat plants before moving them, to reduce that risk to an absolute minimum.

At present we’re in the process of planning a new quarantine facility. Our intention with the new building is that all plant material that is sent to Kew and to our sister-garden, Wakehurst Place in Sussex, will come to this one point—our new “plant reception”—regardless of its origin. This means we can improve our data capture; we can make sure that all incoming material is compliant with the necessary legislation; we can do an initial inspection; and, if we think there’s a risk, we can also do the isolation and screening.

England is not like the United States, where the USDA maintains the plant quarantine service. If, say, the New York Botanical Garden requests plant material from us, they will send us an import permit and shipping labels, and the labels will direct those materials to the USDA quarantine service, who then send the material on. But we operate quite a different system in the UK and European Union.

What happens here at Kew is that we have a licensed quarantine facility, which is approved by FERA and licensed by DEFRA. This gives us the ability to quarantine plant imports that come to the gardens from outside the European Union.

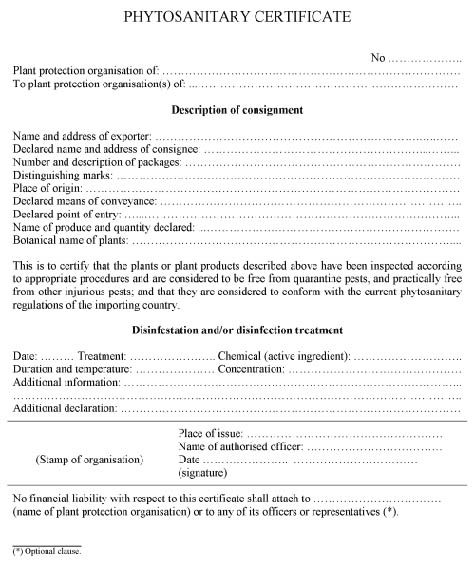

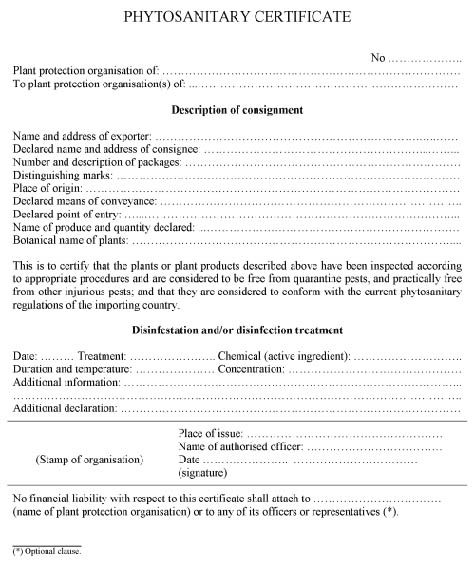

[Image: UK Phytosanitary Certificate, via the Plant Health (England) Order (2005)].

[Image: UK Phytosanitary Certificate, via the Plant Health (England) Order (2005)].

These usually fall into two main types. One is the type of material that comes in with a phytosanitary certificate.

If, for example, somebody went to Costa Rica and they wanted to bring back material from a botanic garden there, they would arrange for all the necessary permissions, but they would also arrange for an inspection by a representative of the national plant protection organization there. If the plant material was free of pests and diseases, it would be issued with a phytosanitary certificate. Normally, that’s only valid for two weeks—so there’s quite a short window of time in which the plant can travel. Once material reaches Kew, it then has to have another inspection—because, at the time it was inspected in Costa Rica, there may have been no visible signs of pests or diseases, but, in the time it takes to reach the UK, something might have developed. So that’s one kind of material that is received into quarantine.

The other type of material we receive into quarantine is what we call “natural source,” or “wild-collected,” material. We operate under a Letter of Authority to import wild-collected material whose movement would normally be prohibited or controlled. An example of that kind of material would be vines from Kyrgyzstan. Their movement is strictly controlled because, in the European Union, vines are a really important crop. You’ll find the same thing in most countries: a lot of cereal crops are controlled, for example, because they can have such a dramatic impact on the horticulture and agriculture of a country.

[Image: Kudzu-infested forest; photo courtesy John D. Byrd, Mississippi State University].

[Image: Kudzu-infested forest; photo courtesy John D. Byrd, Mississippi State University].

BLDGBLOG: Do you ever quarantine controlled or banned plants, such as kudzu or marijuana, to prevent them from entering the country?

Redstone: We wouldn’t normally consider that quarantine. It’s more a case of restricting access of non-authorized people to those plants, or restricting the release of non-native species into the environment. When we quarantine plants, it’s not to do with excluding a particular plant type so much as excluding the diseases or pests that those plants might be harboring.

Invasive plants like kudzu (Pueraria montana) aren’t banned, although we have a few species like Japanese Knotweed (Fallopia japonica) and Giant Hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum) which are illegal to intentionally allow to spread to natural areas.

I’m not sure whether UK authorities would prevent specific plants being imported. Marijuana (Cannabis sativa), whether in THC-containing forms or hemp, requires a Home Office license to produce and process.

We do also provide a service for UK customs authorities. If they make a CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) seizure, we have a department here that will go out to help identify the plant and tell them whether it’s been wild-collected and if it’s of conservation value.

Edible Geography: Can you give any examples of outbreaks that have happened while you’ve been here?

Redstone: We haven’t had any outbreaks here due to failure of quarantine. The impact of an outbreak on our collection could be very serious, particularly if it involves a known quarantine organism where the only sensible treatment is to destroy the plant material. That could cost tens or even hundreds of thousands of pounds to eradicate. It could also threaten rare species, restrict people’s access to the collections, and prevent us from supplying material for research to our own labs and to other botanic gardens.

We have had a couple of recent pest outbreaks in the UK. I’ve already referred to our ongoing Oak Processionary Moth problem. The interesting thing is that when that outbreak happened, the moth wasn’t even recognized as a quarantine organism and it wasn’t clear which government department was going to manage it.

The problem with all of these things is that it’s so much easier to prevent an outbreak than it is to deal with one that’s already in progress. Unlike in the U.S., where you seem to be more geared up to a rapid response once something has been identified, it takes us a long time in the UK and we need more resources in place to do the monitoring and undertake control.

One issue, for example, is making sure we have the right chemicals in place. It’s not enough to do a risk assessment; we also need a list of specific, recommended control measures. And if the recommendation is, for example, “Use this particular chemical,” then we need to make sure that somebody in the UK is able to supply it.

[Image: West Virginia Department of Agriculture’s pest collection, via the Massachusetts Introduced Pests Outreach blog].

[Image: West Virginia Department of Agriculture’s pest collection, via the Massachusetts Introduced Pests Outreach blog].

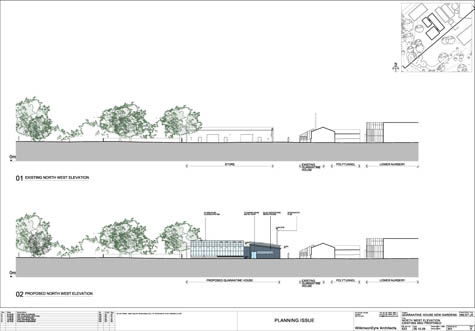

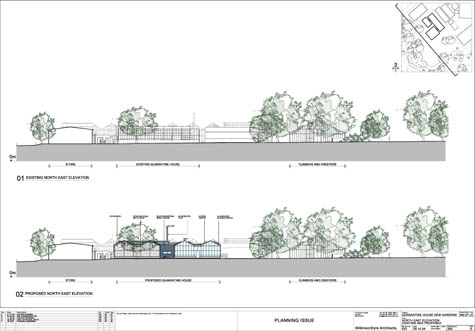

BLDGBLOG: What’s involved in thinking through the design of a new quarantine facility?

Redstone: One of the design challenges is to make sure that we not only meet current legislation, but that we also anticipate some of the changes that might need to happen. Global trade and climate change are having an impact already.

Even trying to decide the scale of our building is a challenge: we want to build-in flexibility, and we don’t want to hamstring the organization in the future. At the same time, we have to be able to afford to run the facility!

What we know from the experience of others is that there have been lots of examples of institutions where they’ve spent vast sums of money—tens of millions of pounds—on creating fabulous infrastructure, but it has then been so expensive to run that they haven’t been able to operate it. We can’t afford that. That’s not what we’re about at Kew.

On the other hand, to contain pests and diseases, we need to assess the risks associated with every single plant movement. As a result, over the past few years we’ve routinely quarantined material that there’s no legal need to quarantine. However, we’ve felt that there was a practical need and a moral obligation to quarantine seed material that comes from, for example, California, or from other states where we know there’s a really severe problem with Sudden Oak Death. Particularly with the understory material, we’ve germinated it all in quarantine and grown it on so that we can screen it. The last thing we want to do is introduce Sudden Oak Death—particularly the American form, because there’s an American and a European strain, and the concern is that the two will meet and produce a super-strain.

The other factor is the human resource. It’s not enough just to have a building: you need to have people who are trained and who understand how to operate it.

[Image: Bay leaves showing symptoms of infection by Phytophthora ramorum, the “causal agent” of Sudden Oak Death. Photo courtesy D. Schmidt, Garbelotto Forest Pathology Lab, UC Berkeley, via the U.S. Department of Energy’s Joint Genome Institute].

[Image: Bay leaves showing symptoms of infection by Phytophthora ramorum, the “causal agent” of Sudden Oak Death. Photo courtesy D. Schmidt, Garbelotto Forest Pathology Lab, UC Berkeley, via the U.S. Department of Energy’s Joint Genome Institute].

Edible Geography: Quarantine is always a question of time. How do you decide how long to grow these understory plants, for example, before you can determine whether they are healthy or sick?

Redstone: That’s all part of the risk assessment process. I work with our local inspector and an excellent scientific support team at FERA to make those kinds of decisions. For example, the inspector might look at a batch of seedlings and say: “That group hasn’t grown very well—but this group is fine, and they’ve reached three months and we can see that they’re still healthy.” What he might then say is, “The healthy ones can move on”—and he’ll do me a release certificate—“but those other ones ought to stay for a little bit longer.” Or he might say: “I don’t like the look of that first group: destroy them.”

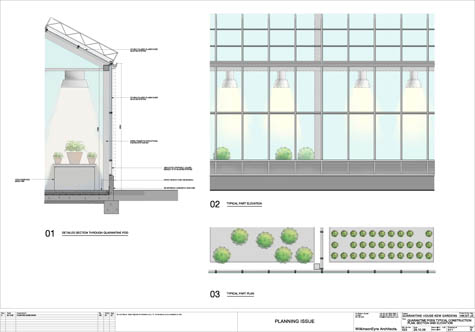

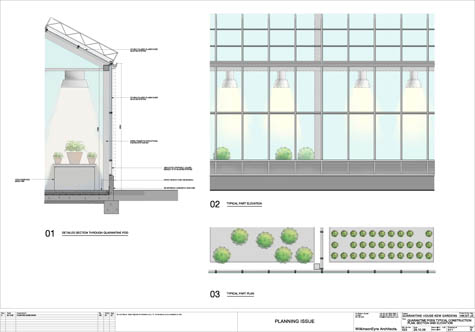

This is always decided on a case-by-case basis—which is very different from genetically-modified organisms, where there are fixed containment levels. What we’ve done with our new building is use the containment levels for GMOs as a guideline when talking to potential suppliers. For example, in terms of treating our water waste, we’re saying to them that we need an equivalent for containment level 3. That means we’re looking at steam-sterilizing all our liquid waste. We’ll take off the solid fraction, and that will be dried and incinerated—or it will be sent through the autoclave—but the liquid will all be steam-sterilized.

The other thing is that all the technology we use needs to be proven and validated. For example, I know of some places where they use an ultraviolet system for treating water, but there are potential problems with that, because if you have high levels of organic matter in the water, things can, in fact, survive. We just can’t take that risk, because it might result in us not getting a license. And if you put an awful lot of effort—and millions of pounds—into doing something, then it would be an awful shame to fail just for the sake of wanting to try something new and cool.

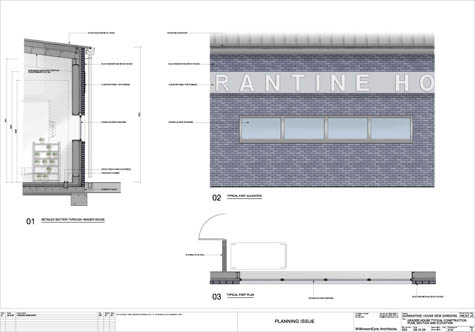

[Image: Proposed façade for the new Quarantine House at Kew, courtesy of Wilkinson Eyre architects].

[Image: Proposed façade for the new Quarantine House at Kew, courtesy of Wilkinson Eyre architects].

Edible Geography: Where does the innovation and experimentation in quarantine design take place, if not in designing a new facility?

Redstone: That’s the problem—it doesn’t. It’s the kind of thing that somebody somewhere should do so that we can test new systems. The trouble is that resources are usually limited in this area and facilities tend to be expensive both to build and operate well. Usually you can’t afford to experiment.

We do test our systems once they’re in place, of course. With the steam-sterilization system that we’re planning to install, we’ll be regularly inoculating it with particular organisms and then testing the processed material to make sure it works. It’s simple, but it’s effective.

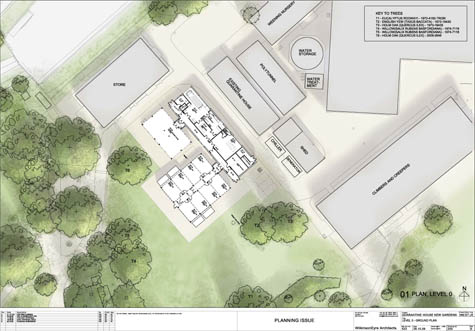

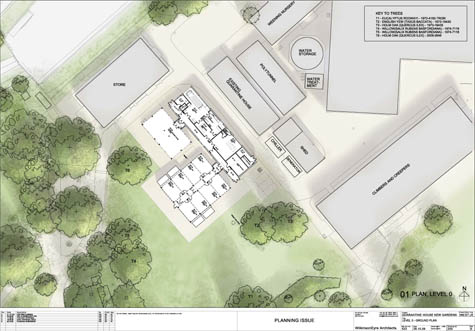

I’ll show you the plans as they stand now. [unfolds plans] In the scheme as it stands, we have a reception area which will receive all plant material that comes into Kew: seeds, bulbs, shrubs, trees, everything—whether it’s from the EU or not.

[Images: Site plan for the new Quarantine House at Kew, showing the proposed site (marked with red, top) and the proposed floor plan of the new structure (bottom). Courtesy of Wilkinson Eyre].

[Images: Site plan for the new Quarantine House at Kew, showing the proposed site (marked with red, top) and the proposed floor plan of the new structure (bottom). Courtesy of Wilkinson Eyre].

Edible Geography: What sort of volume is that?

Redstone: Kew receives, on average, between three to five and half thousand accessions a year, and an accession can be quite a large group of plants—it needn’t necessarily be a single plant, if they’re all genetically identical.

The material will then be processed via the inspection area and then either go into the licensed facility (medium and high containment pods) or into the unlicensed large specimen store. The large specimen store’s primary function is to enable us to hold, monitor and, if necessary, treat or destroy trees, shrubs and other plants originating from within the UK and EU.

The large specimen store is basically what we call a high hat. It has a solid roof, which can be shaded, and insect-proof sides. The insect-proofing is aphid proof, so it’s not particularly small—it’s around the 1mm² mark.

Adjoining the store will be the licensed quarantine facility, which will be split in two: high containment and medium containment. Both spaces will be governed by the licence issued by DEFRA. Both units have air cooling—though they each use a different cooling method—and they’re going to be kept at negative air pressure.

We also have to build in systems to allow for a failure in the power supply. As we’re on the edge of a flood risk zone, the building itself will sit on top of a concrete raft and the plants will be on benches. That will give us quite a lot of leeway as far as any risk from flooding goes. As added protection we also intend to have slots at the doorways; we can then put in barriers and reinforce them with sandbags, in the case of a serious flood. I also want to have an operating procedure that says, if we get advanced warning that there’s going to be a really catastrophic flood event, we’ll load everything in the incinerator and destroy it. Frankly, if that happens, most of London is going to be completely stuffed—so there’ll be bigger problems to deal with!

At the entrance to the licenced area, we’re putting in a cold lobby. It will be kept at 0ºC and it will have a freezer for lab coats. People will put on lab coats before they go into the medium and high containment areas and put them back in the freezer when they come out, where the coats will be sterilized. There will also be an air-circulation fan so that, if anything like seeds or pollen has got stuck to people, it will be blown off into the cold.

[Image: “Gradations of Containment” in the proposed floor plan for the new Quarantine House at Kew, courtesy of Wilkinson Eyre].

[Image: “Gradations of Containment” in the proposed floor plan for the new Quarantine House at Kew, courtesy of Wilkinson Eyre].

Edible Geography: Will there be chemical showers as well?

Redstone: No, that would be considered excessive, to be honest. It’s all about assessing and managing risk proportionately. We’re not a research facility raising pests or diseases for experimentation, so the risks are somewhat less. We have an emergency shower in case somebody’s been contaminated, during pesticide spraying, for example, but our working procedures and precautions like the cold lobby and freezing of lab coats should provide the appropriate level of bio-security.

At every stage, we’re assessing and trying to minimise risk. If we received particularly precious seeds that I thought might harbour a problem, what I would look to do is send them to the seed bank so that they can X-ray them and we can weed out the bad guys straight away, to be destroyed. We also use external treatments – for example, peroxide or other chemicals. Apart from anything else, peroxide is great because it can help trigger germination and is biodegradable.

With everything, you have to give it a bit of thought first. Which is why we say to staff, for goodness sake, please don’t turn up on the doorstep with plant material. We need advance notice so we can risk assess the material.

Other parts of the facility include the loading bay, where there’ll be some storage, the incinerator area, and the inspection bay.

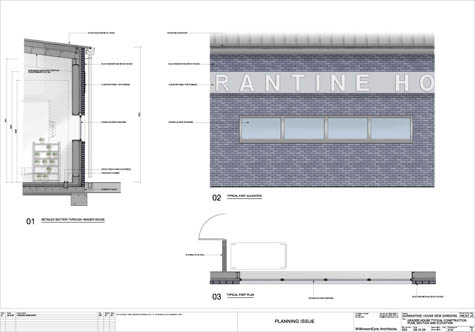

[Image: Wall detail and section of the new Quarantine House at Kew, courtesy of Wilkinson Eyre].

[Image: Wall detail and section of the new Quarantine House at Kew, courtesy of Wilkinson Eyre].

BLDGBLOG: What do you do with the output from the incinerator?

Redstone: The ashes are usually incorporated into the soil heap. It doesn’t go into the compost because it blows around; instead, we usually dig it into the soil piles, so it doesn’t go to waste and it is recycled.

The facility also includes a potting area, which contains a small chemical store and a water-treatment area. And there are going to be insectocutors everywhere!

One important design feature is that the plant room is entirely separate, so that the only way people can enter is through that external door. This means that anyone coming to do maintenance on the electrics or whatever doesn’t have to go through any of the quarantine procedures, because they don’t have access to any other part of the building. It’s human nature to prop open the door if you’re feeling warm—but that sort of thing just can’t be allowed to happen inside the licenced areas.

Edible Geography: How will the temperature-control system work?

Redstone: For the individual zones within the greenhouse, each “pod” will have its own small unit climate control panel on the outside of the house, which will control air circulation, fans, and fogging. We’re going to use fogging not just to control relative humidity, but also, in part, to control temperature gain. It’s quite an effective way of modifying the temperature without huge energy input. And we’re going to use external shading—rollers in tracks—because that’s more efficient than internal shading. Although this is the UK, you may be shocked to hear that heat is the biggest problem we have in maintaining the right kind of environment for our glasshouses.

There’s going to be limited lighting because we’ll be either propagating material or maintaining material—we’re not trying to promote lush growth. There will also be a central computer that controls all the zones, and my intention with the new one is to have direct access from my mobile phone and home computer.

One of the intentions with the new building is to minimize energy costs as much as possible. The building also needs to be capable of being operated by only a few staff—it mustn’t be labor or energy intensive!

For plants that have really critical temperature requirements at the lower end of the spectrum—for example, we had some orchids in from Patagonia—it’s hard to provide those kind of environmental requirements reliably through a glasshouse system. So what we’re going to use is a couple of growth cabinets with lighting, because we feel that’s the most cost-effective solution to that particular headache. We’re also hoping to use rainwater harvesting for part of our irrigation system, and we’re trying to use the most energy-efficient materials.

One of the vendors we’re considering makes quarantine houses using curved polycarbonate sheets. You get a lot of lengthways expansion with polycarbonate sheets, and the curve helps accommodate the expansion and contraction, while maintaining a really good seal. The other thing I like is that we can pump air through a cold water spray and then actually circulate it up and over the curve of the structure, which can give a much more even temperature regime across the bays.

[Image: Curved polycarbonate sheets for glasshouse construction, courtesy Unigro].

[Image: Curved polycarbonate sheets for glasshouse construction, courtesy Unigro].

BLDGBLOG: I see the facility has been designed by Wilkinson Eyre. How is working with them going?

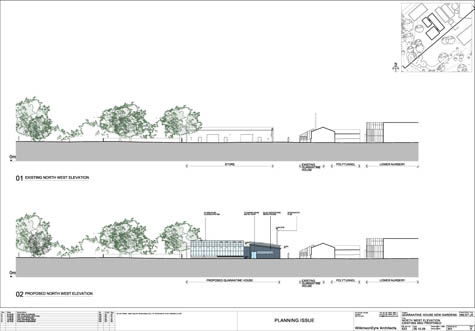

Redstone: Well, the design isn’t finished yet. The final version will be designed and built within the restrictions we’ve incorporated—we are really getting into this now, I think. It’s quite different from anything else they’ve done and the combination of very specific needs, with a lack of specific technical guidelines, makes it a challenging and interesting exercise. We want the building to look attractive, but containment and functionality are its key priorities.

The other interesting design feature is that there’s a five-meter exclusion zone around the building—a completely solid surface with no plant material. We arrived at that measurement through discussion with the Plant Health and Safety Inspectorate, and it’s important to have a clearly marked exclusion zone. Although the old quarantine building began its life being relatively isolated, pressure to use every available square metre of behind-the-scenes space for support activities at Kew means this is no longer the case. We’ve located the new building so we can make use of some of the existing roadway as exclusion. That way we’re not wasting space, and we’re closer to some of the services.

This particular layout also enables us to add on another block, if we need to in the future.

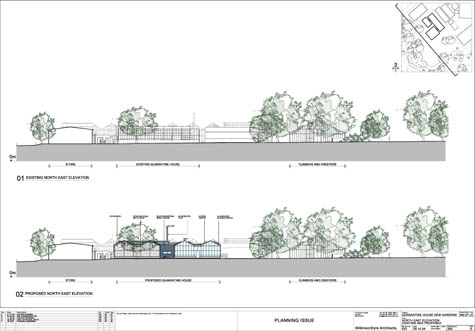

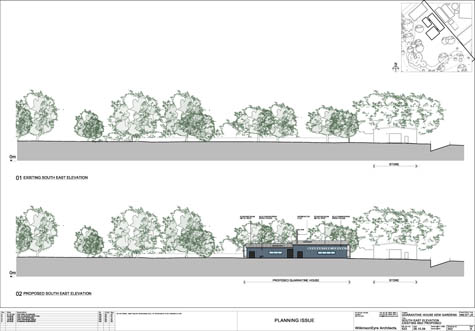

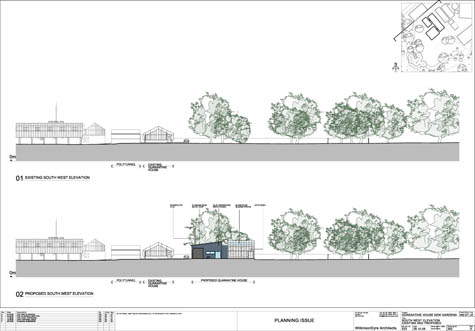

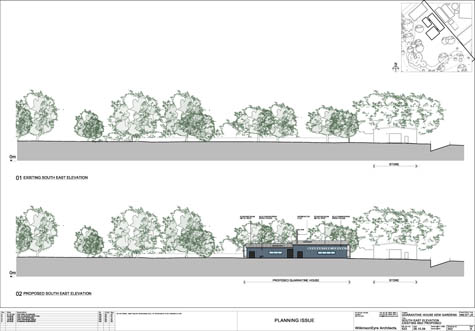

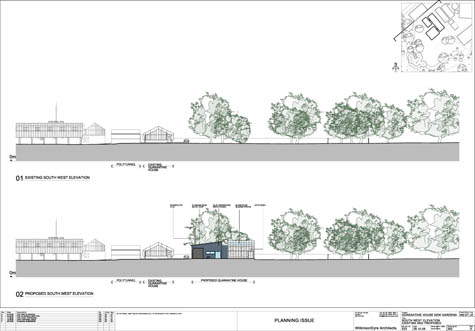

[Images: Proposed elevations—from the NW, NE, SE, and SW—of the new Quarantine House at Kew, courtesy of Wilkinson Eyre].

[Images: Proposed elevations—from the NW, NE, SE, and SW—of the new Quarantine House at Kew, courtesy of Wilkinson Eyre].

Edible Geography: How many plant pest & disease quarantine facilities are there in the UK?

Redstone: A lot of universities have small quarantine facilities, often used for GMO work or raising pests & diseases rather than specifically quarantining plants. Rothamsted have a really excellent facility for experimental work. Central Science Labs at the FERA headquarters in York also have quarantine facilities.

Edible Geography: Does the Royal Horticultural Society have one?

Redstone: No, not that I’m aware of. The National Trust doesn’t have specific quarantine facilities either—although, having said that, they have been working very hard on biosecurity issues, triggered, as they will tell you, by outbreaks of Sudden Oak Death in their collections in the West Country. They have taken stock of the situation and realized that they, like many organizations across the UK, needed to improve current practices. I think it says a lot for the organization that they have been so open and self-critical.

The head of this program for the National Trust is Ian Wright, a head gardener from a Trust property in Cornwall. He realized that through lack of resources, budget challenges, and other difficulties, we’ve moved away from basic good practices: cleaning your materials, cleaning your boots, sterilizing your blades, all those kind of things. For example, if you bring in new plants, you should keep them isolated for a period of time, just to make sure they’re clean—but we seem to have lost a lot of those good habits.

So Ian has worked with David Slawson from FERA to produce a lot of information, as well as posters like this. [unfolds poster] These would go up inside potting sheds, to remind people that quarantine doesn’t have to be fancy. It can be something as simple as a poly-tunnel, or an area behind a shed, where you keep things separate. Containment can be as simple as remembering to wash your boots and wash your hands—basic good hygiene.

In fact, one of the things that we’ve been encouraged to think about by DEFRA is providing a limited commercial service, because there are so few plant quarantine facilities in the UK. This new quarantine facility at RBG Kew will be quite a major one, relative to what’s available in the UK. The thing I’m really excited about is the fact that we’ll have the capacity to control more tightly the stuff that comes in from the European Union and around the UK. That’s increasingly important.

[Image: The National Trust’s “Clean Leaf” plant quarantine poster].

[Image: The National Trust’s “Clean Leaf” plant quarantine poster].

Edible Geography: Did you have any qualms about the decision to locate such a major quarantine facility in the middle of one of the world’s greatest collections of rare and valuable plants?

Redstone: We are in a vulnerable location, in a number of ways. We’ve done a major environmental impact assessment, and even looked at the option of having it off-site, but that in itself created major problems. One of the real issues is that it’s not enough just to have the building; you have to have the human resource.

It also makes sense to have a quarantine facility where the movement occurs. We’re not just accessioning new plant material—we’re also doing quite a bit of repatriation. I think it’s really important that we should be able to return safe material to its country of origin, especially if it’s seriously endangered or on the verge of extinction. We have to be able to hold our hand on our heart and say, “It’s clean, there are no problems, and your only challenge will be making sure it grows and that something doesn’t eat it or squash it.”

It’s not just for stuff coming in—it’s for stuff we’re sending out that quarantine is crucial, too.

BLDGBLOG: How do you interact with the Millennium Seed Bank? Do you quarantine seeds for them?

Redstone: No, they have a quarantine area in their own lab for seed material. However, if they want to grow any controlled or prohibited seeds—for verification by herbarium staff, for example—then that has to be done within our facility. So they can examine seeds, but if they want to germinate them and grow them on, then they have to come here.

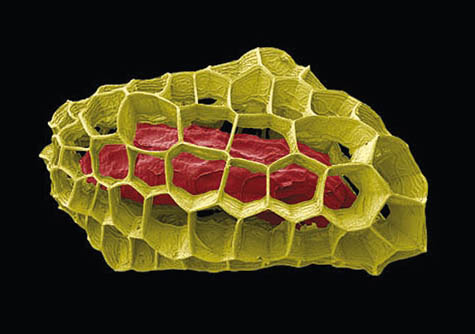

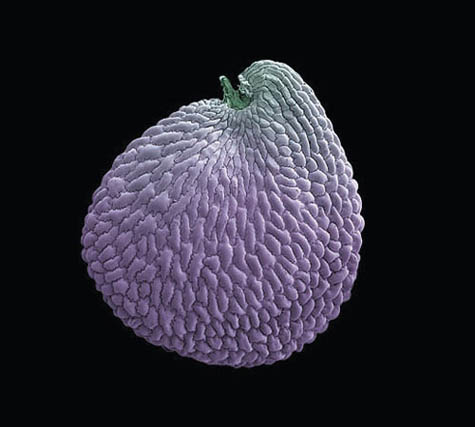

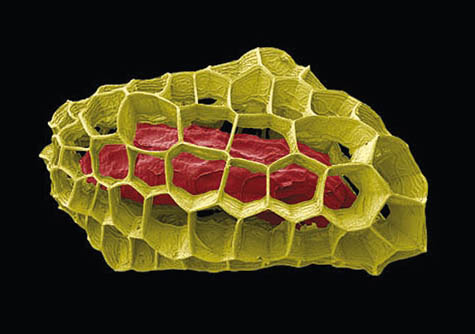

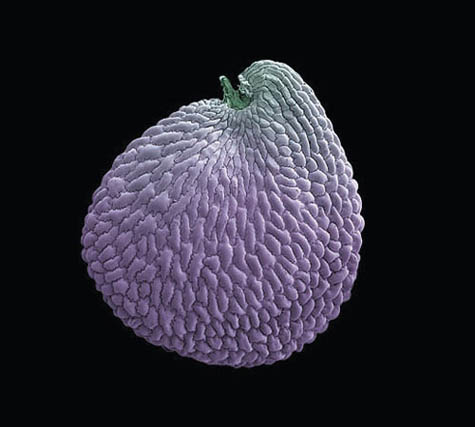

[Image: Electron micrograph images of seeds. (top) Lamourouxia viscosa; (bottom) Franklin’s sandwort, conserved at Kew’s Millennium Seed Bank. Photographs by Rob Kesseler and Madeline Harley, via the The Guardian].

[Image: Electron micrograph images of seeds. (top) Lamourouxia viscosa; (bottom) Franklin’s sandwort, conserved at Kew’s Millennium Seed Bank. Photographs by Rob Kesseler and Madeline Harley, via the The Guardian].

Edible Geography: You mentioned that, in the UK, there isn’t a system where the government gives you the approved quarantine facility plans and you follow them to the letter. How can you be sure your design will qualify for the appropriate license?

Redstone: Well, that’s the case for plant quarantine—the system for GMOs is very different, and I don’t know how animal quarantine operates. In our case, I have constant contact with my colleagues in FERA who will be involved in evaluating the new build plans. If they have an issue with a particular system, they’ll let me know.

For example, I had an inspector on site yesterday who asked, “Have you thought about the door seals? I know that these are really good doors but, to get a good seal, what you want is a little up-stand at the bottom of the door for the seal to butt up against.” It’s all sorts of small details like that.

The difficulty with the project from my point of view has been to make sure it gets enough time and attention now—because I know that if I’m still here when it gets built, my ongoing sanity is going to rely on having made the right choices so that we can physically manage the building. I think that, for projects that are very specialized, like this one, the people who are going to use the buildings often don’t get enough time to actually sit and evaluate what the building needs to do.

Edible Geography: Just writing the brief for it must have been quite a challenge!

Redstone: To say the least. Version 10 got issued about three weeks ago. My biggest worry is that I’ve missed something. There’s just no wriggle room.

Edible Geography: Did you take any of your ideas for your plan from other facilities that you’ve seen?

Redstone Yes. I actually persuaded them to employ a colleague from Rothamsted, Julian Franklin, as a consultant. He is a major quarantine nerd—not only is he really knowledgeable about the plant side of things, but he’s obsessed by technology, so he can tell you that so-and-so needs to be at this many atmospheres, or amps, or whatever. He’s been a real find.

In fact, one of the risks of a project like this is that there are very few experts around—and, especially in the current climate, there are lots of companies who are desperate for work who may claim expertise they don’t really have.

BLDGBLOG: You said you need to avoid innovation at all costs, but is there any aspect of the facility that will be genuinely new or unprecedented?

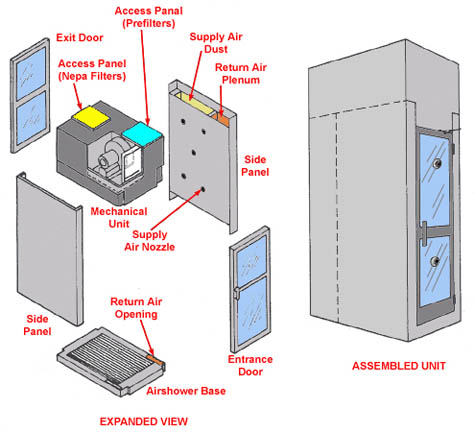

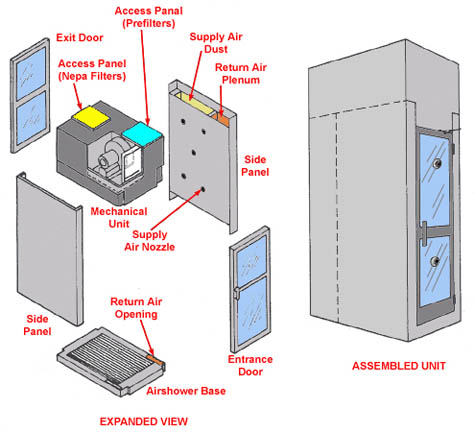

Redstone:: Nobody’s built a screening house quite like ours, I don’t think, but it’s really just an adaptation of things that we’ve seen done elsewhere. Ultimately, it will all be technology that’s been used elsewhere, but perhaps not in quite the same way. Other facilities have air showers, for example, but most of those haven’t also had a cold lobby. We are combining things—but we’re also trying to play safe.

[Image: Air Shower diagram, via the U.S. Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA)].

[Image: Air Shower diagram, via the U.S. Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA)].

Edible Geography: What is the old quarantine facility like—and what will happen to it once the new building is completed?

Sara Redstone: It’s a modified commercial glasshouse, about twenty-five years old. It wasn’t specifically designed as a quarantine house: it has no automatic shading, and controlling the internal climates reliably can be a challenge. The water here is very hard, as well, so the building has had a lot of issues with equipment.

The new facility should be operational by late autumn 2010. This time next year, we’ll be thinking about doing the smoke tests and the pressure tests and so on. And once stuff has been screened in the new facility, it will go into the old house and be held there for short periods of time until it goes onward to the display houses.

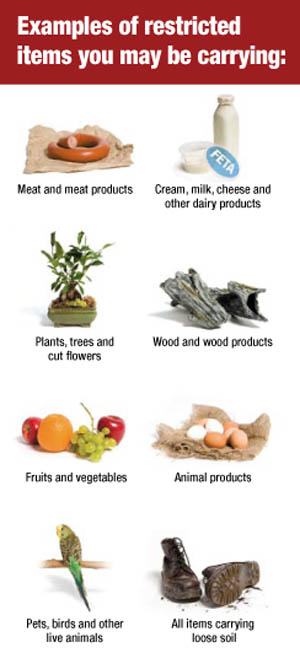

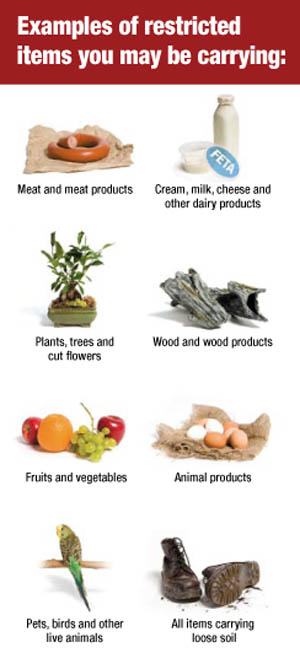

[Image: A fairly standard list of materials that must be declared at the border and potentially quarantined to prevent the import of pests and diseases; this particular brochure is Canadian].

[Image: A fairly standard list of materials that must be declared at the border and potentially quarantined to prevent the import of pests and diseases; this particular brochure is Canadian].

BLDGBLOG: I’m also curious about what happens off-site—for instance, if there is an outbreak somewhere in the Midlands or up in Yorkshire, do you have a field quarantine unit of some sort who can rush out and seal the place off in situ?

Redstone: Not yet, that I know of. You’d need to talk to DEFRA and the Non-Native Species Secretariat who monitor and deal with invasive alien species, or IAS. There is a working group working on developing a protocol for a rapid response against non-native species—NNS—but I’m not sure if they have agreed the way forward.

If the outbreak relates to plants then you’d have to notify—depending on what the host and pest or disease is—either FERA or the Forestry Commission. If the organism isn’t quarantine-listed, then a pest risk analysis (PRA) and other detailed work may be required, and this can take some time to do thoroughly. Depending on where the outbreak is and what it is, there’s then also the need to identify who will attempt to eradicate it and how—and where the resources will come from.

What we really need to do is make everybody aware of the dangers of moving plants. It doesn’t matter if you’re a business or an individual.

I had a person tell me recently that they deliberately altered their suitcase so that they could bring back cuttings from their holidays overseas without being detected. People get very confessional—when they hear what my job is, they have this urge to tell me about all of the plant material they’ve brought through customs without declaring, or all of the farms they visited overseas and didn’t mention on their immigration forms. It’s my worst nightmare.

There have been outbreaks of quite serious pest problems in botanic gardens and plant collections. These have probably, according to the experts at FERA, been the result of things like exotic flower arrangements or of bringing in fruits from around the world to explain to children about plants. Those routes need to be cut off, as well.

Individuals can sometimes be ignorant of the impact they could have by smuggling—in fact, sometimes they don’t even realize that they are smuggling—plant material into and out of the country. We’ve got a bit of money as part of the project to actually do some interpretation on site. I’m hoping that we can do quite a lot to explain to people the risks of moving plant material, and the impact of plant pests and diseases, by having signage in the display houses and in public areas on site.

For example, did you realize that there’s a risk, when you’re moving plants that have soil around the roots, of introducing a pest called the small hive beetle, which can eradicate honeybees? Bees are getting a lot of press at the moment—for very good reason—and so one of the things I’m hoping we can do is use that sort of example to show that the consequences when you smuggle that plant back from your holiday, or when you bring back a jar of local honey, or wax candles, or a wooden sculpture, may be more far reaching than you realize.

If you put things in context, most people are responsible enough not to flout the rules—I hope. We’re all in this together—we all share the same planet.

• • •This autumn in New York City,

Edible Geography and BLDGBLOG have teamed up to lead an 8-week

design studio focusing on the spatial implications of quarantine; you can read more about it

here. For our studio participants, we have been assembling a coursepack full of original content and interviews—but we decided that we should make this material available to everyone so that even those people who are not in New York City, and not enrolled in the quarantine studio, can follow along, offer commentary, and even be inspired to pursue projects of their own.

For other interviews in our quarantine series, check out Until Proven Safe: An Interview with Krista Maglen, One Million Years of Isolation: An interview with Abraham Van Luik, Isolation or Quarantine: An Interview with Dr. Georges Benjamin, Extraordinary Engineering Controls: An Interview with Jonathan Richmond, On the Other Side of Arrival: An Interview with David Barnes, The Last Town on Earth: An Interview with Thomas Mullen, and Biology at the Border: An Interview with Alison Bashford.

More interviews are forthcoming.

Keep your eye out for a copy of the magazine, however, because the following text is accompanied by a fold-out world map, featuring many of the sites revealed by Wikileaks.

Keep your eye out for a copy of the magazine, however, because the following text is accompanied by a fold-out world map, featuring many of the sites revealed by Wikileaks.  [Image: A manganese mine in Gabon, courtesy of the Encyclopedia Britannica].

[Image: A manganese mine in Gabon, courtesy of the Encyclopedia Britannica]. [Image: The Robert-Bourassa generating station, part of the James Bay Project by Hydro Québec; photo courtesy of Hydro Québec].

[Image: The Robert-Bourassa generating station, part of the James Bay Project by Hydro Québec; photo courtesy of Hydro Québec].

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the  [Image: Modeling sea-level rise in Florida, courtesy of

[Image: Modeling sea-level rise in Florida, courtesy of  [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ —

— —

—

[Image: U.S./Mexico border marker #184; photograph by

[Image: U.S./Mexico border marker #184; photograph by  [Image: Map showing a straight baseline separating internal waters from zones of maritime jurisdiction; via

[Image: Map showing a straight baseline separating internal waters from zones of maritime jurisdiction; via  [Image: The Dariel Pass in the Caucausus Mountains, rumored possible site of the mythic

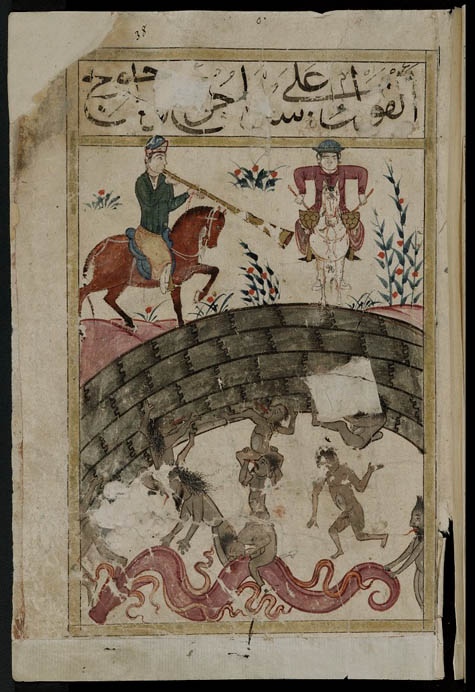

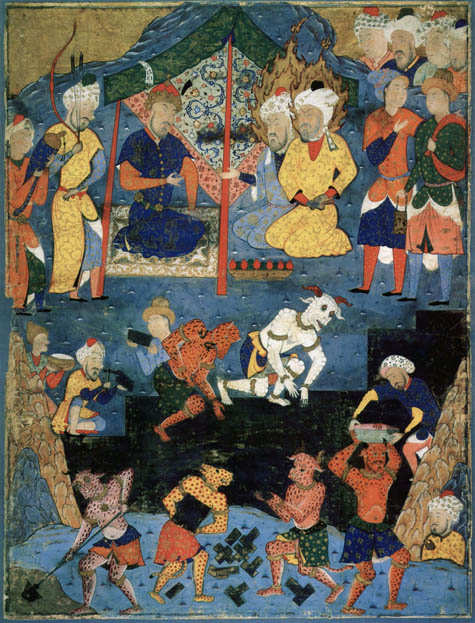

[Image: The Dariel Pass in the Caucausus Mountains, rumored possible site of the mythic  [Image: Constructing the wall of Dhul-Qarnayn, mythic isotope to Alexander’s Gates].

[Image: Constructing the wall of Dhul-Qarnayn, mythic isotope to Alexander’s Gates]. [Image: The geography of Us vs. Them, in a “12th century map by the Muslim scholar Al-Idrisi. ‘Yajooj’ and ‘Majooj’ (Gog and Magog) appear in Arabic script on the bottom-left edge of the Eurasian landmass, enclosed within dark mountains, at a location corresponding roughly to Mongolia.” Via

[Image: The geography of Us vs. Them, in a “12th century map by the Muslim scholar Al-Idrisi. ‘Yajooj’ and ‘Majooj’ (Gog and Magog) appear in Arabic script on the bottom-left edge of the Eurasian landmass, enclosed within dark mountains, at a location corresponding roughly to Mongolia.” Via  [Image: Constructing the wall of Dhul-Qarnayn, via

[Image: Constructing the wall of Dhul-Qarnayn, via  [Image: A map of the

[Image: A map of the  [Image: 55 of Europe’s most common plant pests in a wall poster found via the

[Image: 55 of Europe’s most common plant pests in a wall poster found via the  [Image: A diseased pear from the USDA

[Image: A diseased pear from the USDA  [Images: (left) The Oak Processionary Moth, pictured in a 2007 Daily Mail article titled: “Gardeners are mercilessly hunting down moths

[Images: (left) The Oak Processionary Moth, pictured in a 2007 Daily Mail article titled: “Gardeners are mercilessly hunting down moths  [Image: Sample “Plant Passport” from DEFRA’s

[Image: Sample “Plant Passport” from DEFRA’s  [Image: Healthy and diseased plants in a side-by-side comparison, via the USDA

[Image: Healthy and diseased plants in a side-by-side comparison, via the USDA  [Image: UK Phytosanitary Certificate, via the

[Image: UK Phytosanitary Certificate, via the  [Image: Kudzu-infested forest; photo courtesy John D. Byrd,

[Image: Kudzu-infested forest; photo courtesy John D. Byrd,  [Image: West Virginia Department of Agriculture’s pest collection, via the Massachusetts

[Image: West Virginia Department of Agriculture’s pest collection, via the Massachusetts  [Image: Bay leaves showing symptoms of infection by Phytophthora ramorum, the “causal agent” of Sudden Oak Death. Photo courtesy D. Schmidt, Garbelotto Forest Pathology Lab, UC Berkeley, via the U.S. Department of Energy’s

[Image: Bay leaves showing symptoms of infection by Phytophthora ramorum, the “causal agent” of Sudden Oak Death. Photo courtesy D. Schmidt, Garbelotto Forest Pathology Lab, UC Berkeley, via the U.S. Department of Energy’s  [Image: Proposed façade for the new Quarantine House at Kew, courtesy of

[Image: Proposed façade for the new Quarantine House at Kew, courtesy of

[Images: Site plan for the new Quarantine House at Kew, showing the proposed site (marked with red, top) and the proposed floor plan of the new structure (bottom). Courtesy of

[Images: Site plan for the new Quarantine House at Kew, showing the proposed site (marked with red, top) and the proposed floor plan of the new structure (bottom). Courtesy of  [Image: “Gradations of Containment” in the proposed floor plan for the new Quarantine House at Kew, courtesy of

[Image: “Gradations of Containment” in the proposed floor plan for the new Quarantine House at Kew, courtesy of  [Image: Wall detail and section of the new Quarantine House at Kew, courtesy of

[Image: Wall detail and section of the new Quarantine House at Kew, courtesy of  [Image: Curved polycarbonate sheets for glasshouse construction, courtesy

[Image: Curved polycarbonate sheets for glasshouse construction, courtesy

[Images: Proposed elevations—from the NW, NE, SE, and SW—of the new Quarantine House at Kew, courtesy of

[Images: Proposed elevations—from the NW, NE, SE, and SW—of the new Quarantine House at Kew, courtesy of  [Image: The National Trust’s “Clean Leaf” plant quarantine poster].

[Image: The National Trust’s “Clean Leaf” plant quarantine poster].

[Image: Electron micrograph images of seeds. (top)

[Image: Electron micrograph images of seeds. (top)  [Image: Air Shower diagram, via the U.S.

[Image: Air Shower diagram, via the U.S.  [Image: A fairly standard list of materials that must be declared at the border and potentially quarantined to prevent the import of pests and diseases; this particular brochure is

[Image: A fairly standard list of materials that must be declared at the border and potentially quarantined to prevent the import of pests and diseases; this particular brochure is  [Image: Airfield at Guantanamo Bay converted for the quarantine of 10,000 Haitian migrants; via

[Image: Airfield at Guantanamo Bay converted for the quarantine of 10,000 Haitian migrants; via  [Image:

[Image:  [Images: Asian immigrants arriving at the Angel Island immigration station, San Francisco, and a man quarantined at Ellis Island; courtesy of the

[Images: Asian immigrants arriving at the Angel Island immigration station, San Francisco, and a man quarantined at Ellis Island; courtesy of the  [Image: “Testing an Asian immigrant” at the Angel Island immigration station, San Francisco; courtesy of the

[Image: “Testing an Asian immigrant” at the Angel Island immigration station, San Francisco; courtesy of the  [Image: Medical inspection station at Ellis Island. The 1891 U.S. immigration law called for the exclusion of “all idiots, insane persons, paupers or persons likely to become public charges, persons suffering from a loathsome or dangerous contagious disease,” as well as criminals. Courtesy of the

[Image: Medical inspection station at Ellis Island. The 1891 U.S. immigration law called for the exclusion of “all idiots, insane persons, paupers or persons likely to become public charges, persons suffering from a loathsome or dangerous contagious disease,” as well as criminals. Courtesy of the  [Image: Isolation Section,

[Image: Isolation Section,  [Image: A “Quarantine Act” banner from the Torrens Island Quarantine Station collection, held by the

[Image: A “Quarantine Act” banner from the Torrens Island Quarantine Station collection, held by the  [Image: View through the perimeter fence at Port Hedland Immigration Reception and Processing Centre in Western Australia, June 2002, from the

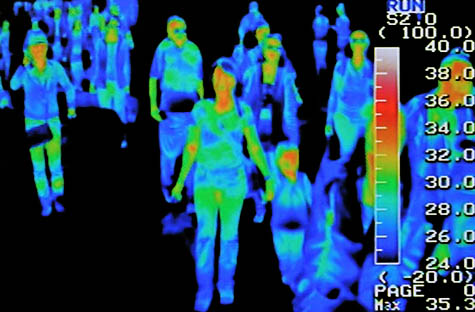

[Image: View through the perimeter fence at Port Hedland Immigration Reception and Processing Centre in Western Australia, June 2002, from the  [Image: Thermal scanners at the Seoul international airport; photo by Jung Yeon-Je for Reuters, via

[Image: Thermal scanners at the Seoul international airport; photo by Jung Yeon-Je for Reuters, via  [Image: Map of

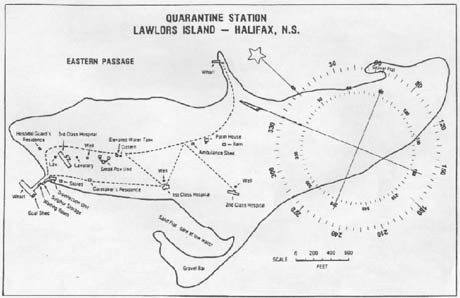

[Image: Map of

[Images: (top) The North Head Quarantine Station, Manly, Australia; photo by

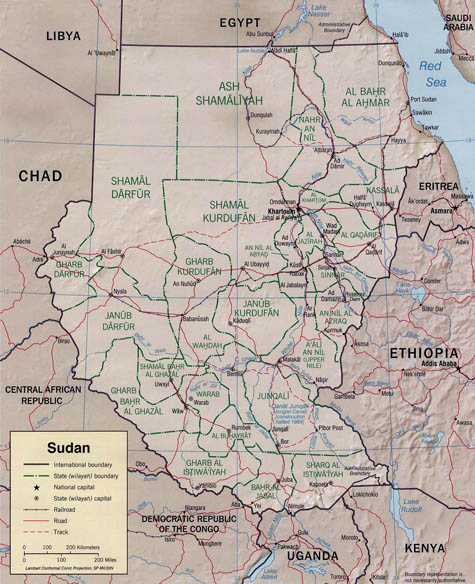

[Images: (top) The North Head Quarantine Station, Manly, Australia; photo by  [Image: As Egypt and Sudan gained their independence from Britain, the border between the two countries was determined by drawing a straight line from the sea through

[Image: As Egypt and Sudan gained their independence from Britain, the border between the two countries was determined by drawing a straight line from the sea through  [Images:

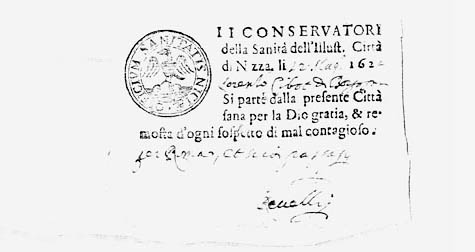

[Images:  [Image: An Italian Health Passport, via the

[Image: An Italian Health Passport, via the  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Professor Igor Panarin’s six-fold vision of

[Image: Professor Igor Panarin’s six-fold vision of