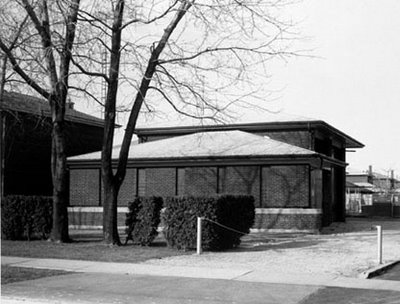

[Image: The monastery of Mont-Sainte-Odile; photo via Wikipedia].

[Image: The monastery of Mont-Sainte-Odile; photo via Wikipedia].

I’ve got an article in the (apparently very delayed) “Summer 2015” issue of Cabinet Magazine, that only came out earlier this week, looking at rare-book theft and the architecture of burglary. The article is also a nice introduction to many of the themes in A Burglar’s Guide to the City, due out in April.

Called “Inside Jobs,” the essay looks at two rare-book thieves. One was an almost Jules Verne-like guy who broke into the monastery of Mont-Sainte-Odile in the mountains of eastern France after discovering an old floor plan of the place in an archive.

That document—and this sounds like something straight out of an Umberto Eco novel—revealed a secret passageway that twisted down from an attic to the monks’ library through the back of a cabinet, which, of course, became his preferred method of entry.

The other guy was one of the most prolific book thieves in U.S. history, whose escapades in the rare book collection of the University of Southern California occurred by means of the library’s old dumbwaiter system. Although the dumbwaiter itself was no longer in use, the shafts were still there, hidden inside the wall, connecting floor to floor. By crawling through the dumbwaiter, he basically brought those dead spaces back into use.

In both cases, I suggest, these men’s respective crimes were “made possible by the reawakening of a dormant interior, one disguised by and simultaneous with the buildings’ visible rooms. There was another building inside each building, we might say, a deeper interior within the interior. Their burglaries thus both depended on and operated through an act of spatial revelation: bringing to light illicit connections between two internal points previously seen as separate.”

Indeed, in both cases the actual theft of books seems strangely anti-climactic, even boring, merely a graduated form of shoplifting. Rather, it is the way these crimes were committed that bears such sustained consideration. The burglars’ rehabilitation of a quiescent architectural space brings with it a much broader and more troubling implication that we ourselves do not fully understand the extent of the rooms and corridors around us, that the walls we rely on for solidity might in fact be hollow, and that there are ways of moving through any building, passing from one floor to another, that are so architecturally unexpected as to bear comparison to animal life or even the supernatural. In the end, burglars—dark figures burrowing along the periphery of the world—need not steal a thing to accomplish their most unsettling revelation.

Check it out, if you get the chance, and consider pre-ordering a copy of A Burglar’s Guide to the City, if these sorts of things are of interest.

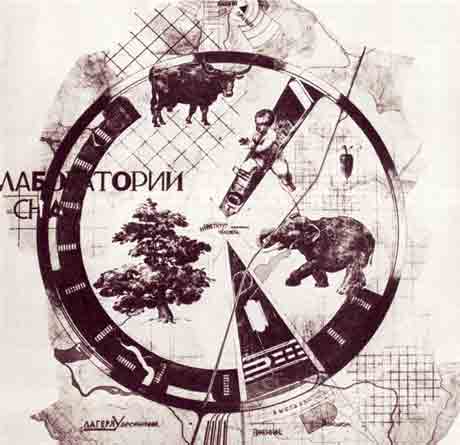

[Image: A “garden suburb” outside Moscow. Via

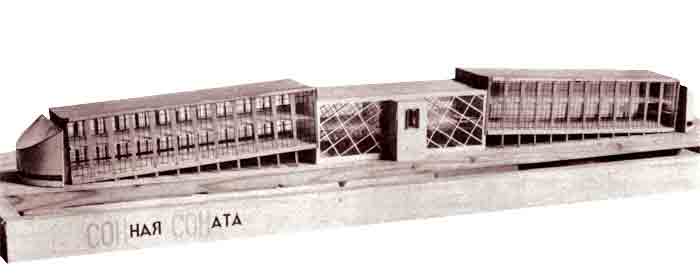

[Image: A “garden suburb” outside Moscow. Via  [Image: Konstantin Melnikov’s “Sonata of Sleep.” Via

[Image: Konstantin Melnikov’s “Sonata of Sleep.” Via  [Image: Konstantin Melnikov’s “

[Image: Konstantin Melnikov’s “