[Image: Shiitake logs on racks in the Mittagong mushroom tunnel. All photos by the author].

[Image: Shiitake logs on racks in the Mittagong mushroom tunnel. All photos by the author].

Note: This is a guest post by Nicola Twilley.

As Geoff mentioned here on BLDGBLOG a few weeks ago, we spent our last full day in Australia touring the Li-Sun Exotic Mushroom Farm with its founder and owner, Dr. Noel Arrold. Three weeks earlier, at a Sydney farmers’ market, we had been buying handfuls of his delicious Shimeji and Chestnut mushrooms to make a risotto, when the vendor told us that they’d all been grown in a disused railway tunnel southwest of the city, in Mittagong.

[Image: The mushroom tunnel, on the left, was originally built in 1886 to house a single-track railway line. By 1919, it had to be replaced with the still-functioning double-track tunnel to its right, built to cope with the rise in traffic on the route following the founding of Canberra, Australia’s purpose-built capital city. The tunnel is still state property: the mushroom farm exists on a five-year lease].

[Image: The mushroom tunnel, on the left, was originally built in 1886 to house a single-track railway line. By 1919, it had to be replaced with the still-functioning double-track tunnel to its right, built to cope with the rise in traffic on the route following the founding of Canberra, Australia’s purpose-built capital city. The tunnel is still state property: the mushroom farm exists on a five-year lease].

The idea of re-purposing abandoned civic infrastructure as a site for myco-agriculture was intriguing, to say the least, so we were thrilled when Dr. Arrold kindly agreed to take the time to give us a tour (Li-Sun is not usually open to the public).

Dr. Arrold has been growing mushrooms in the Mittagong tunnel for more than twenty years, starting with ordinary soil-based white button mushrooms and Cremini, before switching to focus on higher maintenance (and more profitable) exotics such as Shimeji, Wood-ear, Shiitake, and Oyster mushrooms.

[Images: (top) Dr. Arrold with a bag of mushroom spawn. He keeps his mushroom cultures in test-tubes filled with boiled potato and agar, and initially incubates the spawn on rye or wheat grains in clear plastic bags sealed with sponge anti-mould filters before transferring it to jars, black bin bags, or plastic-wrapped logs; (middle) Shimeji and (bottom) pink oyster mushrooms cropping on racks inside the tunnel. Dr. Arrold came up with the simple but clever idea of growing mushrooms in black bin bags with holes cut in them. Previously, mushrooms were typically grown inside clear plastic bags. The equal exposure to light meant that the mushrooms fruited all over, which made it harder to harvest without missing some].

[Images: (top) Dr. Arrold with a bag of mushroom spawn. He keeps his mushroom cultures in test-tubes filled with boiled potato and agar, and initially incubates the spawn on rye or wheat grains in clear plastic bags sealed with sponge anti-mould filters before transferring it to jars, black bin bags, or plastic-wrapped logs; (middle) Shimeji and (bottom) pink oyster mushrooms cropping on racks inside the tunnel. Dr. Arrold came up with the simple but clever idea of growing mushrooms in black bin bags with holes cut in them. Previously, mushrooms were typically grown inside clear plastic bags. The equal exposure to light meant that the mushrooms fruited all over, which made it harder to harvest without missing some].

A microbiologist by training, Dr. Arrold originally imported his exotic mushroom cultures into Australia from their traditional homes in China, Japan, and Korea. Like a latter-day Tradescant, he regularly travels abroad to keep up with mushroom growing techniques, share his own innovations (such as the black plastic grow-bags shown above), and collect new strains.

He showed us a recent acquisition, which he hunted down after coming across it in his dinner in a café in Fuzhou, and which he is currently trialling as a potential candidate for cultivation in the tunnel. Even though all his mushroom strains were originally imported from overseas (disappointingly, given its ecological uniqueness, Australia has no exciting mushroom types of its own), Dr. Arrold has refined each variety over generations to suit the conditions in this particular tunnel.

Since there is currently only one other disused railway tunnel used for mushroom growing in the whole of Australia, his mushrooms have evolved to fit an extremely specialised environmental niche: they are species designed for architecture.

[Images: (top) Logs on racks (Taiwanese style) and mounted on the wall (Chinese style) in the tunnel; (bottom) Wood-ear mushrooms grow through diagonal slashes in plastic bags filled with chopped wheat straw].

[Images: (top) Logs on racks (Taiwanese style) and mounted on the wall (Chinese style) in the tunnel; (bottom) Wood-ear mushrooms grow through diagonal slashes in plastic bags filled with chopped wheat straw].

The tunnel for which these mushrooms have been so carefully developed is 650 metres long and about 30 metres deep. Buried under solid rock and deprived of the New South Wales sunshine, the temperature holds at a steady 15º Celsius. The fluorescent lights flick on at 5:30 a.m. every day, switching off again exactly 12 hours later. The humidity level fluctuates seasonally, and would reach an unacceptable aridity in the winter if Dr. Arrold didn’t wet the floors and run a fogger during the coldest months.

In all other respects, the tunnel is an unnaturally accurate concrete and brick approximation of the prevailing conditions in the mushroom-friendly deep valleys and foggy forests of Fujian province. This inadvertent industrial replicant ecosystem made me think of Swiss architecture firm Fabric‘s 2008 proposal for a “Tower of Atmospheric Relations” (pdf).

[Image: Renderings of Fabric’s “Tower of Atmospheric Relations,” showing the stacked volumes of air and the resulting climate simulations].

[Image: Renderings of Fabric’s “Tower of Atmospheric Relations,” showing the stacked volumes of air and the resulting climate simulations].

Fabric’s ingenious project is designed to generate a varying set of artificial climates (such as the muggy heat of the Indian monsoon, or the crisp air of a New England autumn day) entirely through the movements of the air that is trapped inside the tower’s architecture (i.e. by means of convection, condensation, thermal inertia, and so on).

If you could perhaps combine this kind of atmosphere-modifying architecture with today’s omnipresent vertical farm proposals, northern city dwellers could simultaneously avoid food miles and continue to enjoy bananas.

[Images: (top) Li-Sun employees unwrap mushroom logs before putting them on racks in the tunnel. The logs are made by mixing steamed bran or wheat, sawdust from thirty-year-old eucalyptus, and lime in a concrete mixer, packing it into plastic cylinders, and inoculating them with spawn. (middle) Fruiting Shiitake logs on racks in the tunnel. Once their mushrooms are harvested, the logs make great firewood. (bottom) The Shiitake log shock tank – Dr. Arrold explained that the logs crop after one week in the tunnel, and then sit dormant for three weeks, until they are “woken up” with a quick soak in a tub of water, after which they are productive for three or four more weeks. “Shiitake,” said Dr. Arrold, in a resigned tone, “are the most trouble – and the biggest market.”]

[Images: (top) Li-Sun employees unwrap mushroom logs before putting them on racks in the tunnel. The logs are made by mixing steamed bran or wheat, sawdust from thirty-year-old eucalyptus, and lime in a concrete mixer, packing it into plastic cylinders, and inoculating them with spawn. (middle) Fruiting Shiitake logs on racks in the tunnel. Once their mushrooms are harvested, the logs make great firewood. (bottom) The Shiitake log shock tank – Dr. Arrold explained that the logs crop after one week in the tunnel, and then sit dormant for three weeks, until they are “woken up” with a quick soak in a tub of water, after which they are productive for three or four more weeks. “Shiitake,” said Dr. Arrold, in a resigned tone, “are the most trouble – and the biggest market.”]

Outside of the tunnel, Dr. Arrold also grows Enoki, King Brown, and Chestnut mushrooms. These varieties prefer different temperatures (6º, 17º, and 18º Celsius respectively), so they are housed in climate-controlled Portakabins.

[Images: (top) The paper cone around the top of the enoki jar helps the mushrooms grow tall and thin. (second) Chestnut mushrooms grow in jars for seven weeks: four to fruit, and three more to sprout to harvest size above the jar’s rim. (third) Thousands of mushroom jars are stacked from floor to ceiling. Dr. Arrold starting growing these mushroom varieties in jars two years ago, and hasn’t had a holiday since. (fourth) Empty mushroom jars are sterilised in the autoclave between crops, so that disease doesn’t build up. (bottom) The clean jars are filled with sterilised substrate using a Japanese-designed machine, before being inoculated with spawn].

[Images: (top) The paper cone around the top of the enoki jar helps the mushrooms grow tall and thin. (second) Chestnut mushrooms grow in jars for seven weeks: four to fruit, and three more to sprout to harvest size above the jar’s rim. (third) Thousands of mushroom jars are stacked from floor to ceiling. Dr. Arrold starting growing these mushroom varieties in jars two years ago, and hasn’t had a holiday since. (fourth) Empty mushroom jars are sterilised in the autoclave between crops, so that disease doesn’t build up. (bottom) The clean jars are filled with sterilised substrate using a Japanese-designed machine, before being inoculated with spawn].

The fact that the King Brown and Chestnut mushrooms only thrive at a higher temperature than the railway tunnel provides makes their cultivation much more expensive. Their ecosystem has to be replicated mechanically, rather than occuring spontaneously within disused infrastructure.

I couldn’t help but wonder whether there might be another tunnel, cave, or even abandoned bunker in New South Wales that currently maintains a steady 17º Celsius and is just waiting to be colonised by King Brown mushrooms growing, like ghostly thumbs, out of thousands of glass jars.

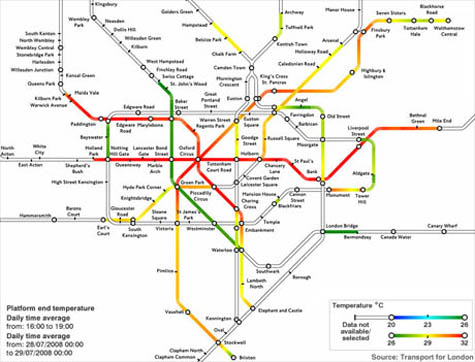

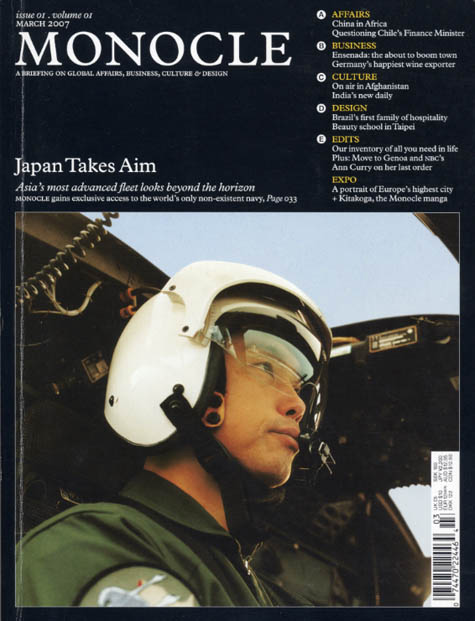

[Image: Temperature map of the London Underground system (via the BBC, where a larger version is also available), compiled by Transport for London’s “Cool the Tube” team].

[Image: Temperature map of the London Underground system (via the BBC, where a larger version is also available), compiled by Transport for London’s “Cool the Tube” team].

In the UK, for instance, Transport for London has kindly provided this fascinating map of summertime temperatures on various tube lines. Most are far too hot for mushroom growing (not to mention commuter comfort). Nonetheless, perhaps the estimated £1.56 billion cost of installing air-conditioning on the surface lines could be partially recouped by putting some of the system’s many abandoned service tunnels and shafts to use cultivating exotic fungi. These mushroom farms would be buried deep under the surface of the city, colonizing abandoned infrastructural hollows and attracting foodies and tourists alike.

[Image: A very amateur bit of Photoshop work: Li-Sun Mushrooms as packaged for Australian supermarket chain Woolworths, re-imagined as Bakerloo Line Oyster Mushrooms].

[Image: A very amateur bit of Photoshop work: Li-Sun Mushrooms as packaged for Australian supermarket chain Woolworths, re-imagined as Bakerloo Line Oyster Mushrooms].

Service shafts along the hot Central line might be perfect for growing Chestnut Mushrooms, while the marginally cooler Bakerloo line has several abandoned tunnels that could replicate the subtropical forest habitat of the Oyster Mushroom. And – unlike Dr. Arrold’s Li-Sun mushrooms, which make no mention of their railway tunnel origins on the packaging – I would hope that Transport for London would cater to the locavore trend by labeling its varietals by their line of origin.

[Images: Shiitake logs on racks in the Mittagong mushroom tunnel].

[Images: Shiitake logs on racks in the Mittagong mushroom tunnel].

Speculation aside, our visit to the Mittagong Mushroom Tunnel was fascinating, and Dr. Arrold’s patience in answering our endless questions was much appreciated. If you’re in Australia, it’s well worth seeking out Li-Sun mushrooms: you can find them at several Sydney markets, as well as branches of Woolworths.

[Image: Nicola Twilley is the author of Edible Geography, where this post has been simultaneously published].

[Image: Painting of a lyrebird by John Gould, courtesy archive.org.]

[Image: Painting of a lyrebird by John Gould, courtesy archive.org.] [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The antenna field at Jim Creek, via

[Image: The antenna field at Jim Creek, via  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Australia, rendered by Neema Mostafavi for

[Image: Australia, rendered by Neema Mostafavi for

[Image: Shiitake logs on racks in the Mittagong mushroom tunnel. All photos by the

[Image: Shiitake logs on racks in the Mittagong mushroom tunnel. All photos by the  [Image: The mushroom tunnel, on the left, was originally built in 1886 to house a single-track railway line. By 1919, it had to be replaced with the still-functioning double-track tunnel to its right, built to cope with the rise in traffic on the route following the founding of

[Image: The mushroom tunnel, on the left, was originally built in 1886 to house a single-track railway line. By 1919, it had to be replaced with the still-functioning double-track tunnel to its right, built to cope with the rise in traffic on the route following the founding of

[Images: (top) Dr. Arrold with a bag of mushroom spawn. He keeps his mushroom cultures in test-tubes filled with boiled potato and agar, and initially incubates the spawn on rye or wheat grains in clear plastic bags sealed with sponge anti-mould filters before transferring it to jars, black bin bags, or plastic-wrapped logs; (middle) Shimeji and (bottom) pink oyster mushrooms cropping on racks inside the tunnel. Dr. Arrold came up with the simple but clever idea of growing mushrooms in black bin bags with holes cut in them. Previously, mushrooms were typically grown inside clear plastic bags. The equal exposure to light meant that the mushrooms fruited all over, which made it harder to harvest without missing some].

[Images: (top) Dr. Arrold with a bag of mushroom spawn. He keeps his mushroom cultures in test-tubes filled with boiled potato and agar, and initially incubates the spawn on rye or wheat grains in clear plastic bags sealed with sponge anti-mould filters before transferring it to jars, black bin bags, or plastic-wrapped logs; (middle) Shimeji and (bottom) pink oyster mushrooms cropping on racks inside the tunnel. Dr. Arrold came up with the simple but clever idea of growing mushrooms in black bin bags with holes cut in them. Previously, mushrooms were typically grown inside clear plastic bags. The equal exposure to light meant that the mushrooms fruited all over, which made it harder to harvest without missing some].

[Images: (top) Logs on racks (Taiwanese style) and mounted on the wall (Chinese style) in the tunnel; (bottom) Wood-ear mushrooms grow through diagonal slashes in plastic bags filled with chopped wheat straw].

[Images: (top) Logs on racks (Taiwanese style) and mounted on the wall (Chinese style) in the tunnel; (bottom) Wood-ear mushrooms grow through diagonal slashes in plastic bags filled with chopped wheat straw]. [Image: Renderings of Fabric’s “Tower of Atmospheric Relations,” showing the stacked volumes of air and the resulting climate simulations].

[Image: Renderings of Fabric’s “Tower of Atmospheric Relations,” showing the stacked volumes of air and the resulting climate simulations].

[Images: (top) Li-Sun employees unwrap mushroom logs before putting them on racks in the tunnel. The logs are made by mixing steamed bran or wheat, sawdust from thirty-year-old eucalyptus, and lime in a concrete mixer, packing it into plastic cylinders, and inoculating them with spawn. (middle) Fruiting Shiitake logs on racks in the tunnel. Once their mushrooms are harvested, the logs make great firewood. (bottom) The Shiitake log shock tank – Dr. Arrold explained that the logs crop after one week in the tunnel, and then sit dormant for three weeks, until they are “woken up” with a quick soak in a tub of water, after which they are productive for three or four more weeks. “Shiitake,” said Dr. Arrold, in a resigned tone, “are the most trouble – and the biggest market.”]

[Images: (top) Li-Sun employees unwrap mushroom logs before putting them on racks in the tunnel. The logs are made by mixing steamed bran or wheat, sawdust from thirty-year-old eucalyptus, and lime in a concrete mixer, packing it into plastic cylinders, and inoculating them with spawn. (middle) Fruiting Shiitake logs on racks in the tunnel. Once their mushrooms are harvested, the logs make great firewood. (bottom) The Shiitake log shock tank – Dr. Arrold explained that the logs crop after one week in the tunnel, and then sit dormant for three weeks, until they are “woken up” with a quick soak in a tub of water, after which they are productive for three or four more weeks. “Shiitake,” said Dr. Arrold, in a resigned tone, “are the most trouble – and the biggest market.”]

[Images: (top) The paper cone around the top of the enoki jar helps the mushrooms grow tall and thin. (second) Chestnut mushrooms grow in jars for seven weeks: four to fruit, and three more to sprout to harvest size above the jar’s rim. (third) Thousands of mushroom jars are stacked from floor to ceiling. Dr. Arrold starting growing these mushroom varieties in jars two years ago, and hasn’t had a holiday since. (fourth) Empty mushroom jars are sterilised in the autoclave between crops, so that disease doesn’t build up. (bottom) The clean jars are filled with sterilised substrate using a Japanese-designed machine, before being inoculated with spawn].

[Images: (top) The paper cone around the top of the enoki jar helps the mushrooms grow tall and thin. (second) Chestnut mushrooms grow in jars for seven weeks: four to fruit, and three more to sprout to harvest size above the jar’s rim. (third) Thousands of mushroom jars are stacked from floor to ceiling. Dr. Arrold starting growing these mushroom varieties in jars two years ago, and hasn’t had a holiday since. (fourth) Empty mushroom jars are sterilised in the autoclave between crops, so that disease doesn’t build up. (bottom) The clean jars are filled with sterilised substrate using a Japanese-designed machine, before being inoculated with spawn]. [Image: Temperature map of the London Underground system (via the

[Image: Temperature map of the London Underground system (via the  [Image: A very amateur bit of Photoshop work: Li-Sun Mushrooms as packaged for Australian supermarket chain

[Image: A very amateur bit of Photoshop work: Li-Sun Mushrooms as packaged for Australian supermarket chain

[Images: Shiitake logs on racks in the Mittagong mushroom tunnel].

[Images: Shiitake logs on racks in the Mittagong mushroom tunnel]. I’ve only got the first issue, however, so I’m not exactly an informed reader; and I won’t be performing a rigorous review of the magazine here – discussing its design, intentions, etc. etc. etc. I simply want to point out a few cool articles that have an architectural or landscape bent.

I’ve only got the first issue, however, so I’m not exactly an informed reader; and I won’t be performing a rigorous review of the magazine here – discussing its design, intentions, etc. etc. etc. I simply want to point out a few cool articles that have an architectural or landscape bent.  [Image: Gotthard Base Tunnel, via

[Image: Gotthard Base Tunnel, via  [Image: The launcher for a UAV; courtesy of

[Image: The launcher for a UAV; courtesy of  [Image: The lighting technologies of

[Image: The lighting technologies of  [Image: The International Space Station].

[Image: The International Space Station].